by Xiaolai Li, rewritten in English by John Gordon & Xiaolai Li ©2019

While the financial trading markets are no doubt the best place to make money through critical thinking and the application of knowledge, there is also no other place where people are more severely punished for a lack of critical thinking.

Investing is risky, so make your decisions carefully!

As Howard Stanley Marks, who was listed as the 374th wealthiest person in the United States in 2017, once said:

“There are old investors, and there are bold investors, but there are no old bold investors.”

Don’t be so naïve as to believe that you can turn into a superman just because you learned something new yesterday. Translating knowledge into meaningful action takes much more time than you’ve ever imagined. Relax, take it easy, and don’t rush. You can lift a very heavy weight, but without proper training you can hurt yourself.

It’s been ten years since I published Befriending Time, and it’s still a bestseller. While I was writing the book, I tried to adhere to the following principle:

Will this book still be useful to readers in ten years?

In addition to being bestsellers, my books are often perennial sellers. The above-mentioned principle is my secret for writing many perennial sellers, which is simple, direct, brutal and effective.

Because I have been writing in this simple, direct, brutal and effective way for so long, I have a deep understanding of the following fact:

Solving the single most important problem can directly avoid the problems that so many others face.

Actually, most problems in life are due to failing to resolve the most important problem right from the start. If you can handle the most important problem in the beginning, then even though there will still be many other difficulties, they won’t be the eternal problems that so many people face.

When facing the few truly essential decisions in life, many people also ignore the most important problem. For instance, when choosing whom to marry, “Is she or he reasonable?” is always outside the scope of consideration, even though it is the single most important factor. Instead, they focus on appearance, education, background, etc., without considering which factor will be the most important in the future. Of course, maybe this is because they themselves aren’t a reasonable person (yes, it’s true, most people aren’t very reasonable, and they stay this way throughout their lives).

Because they haven’t eradicated the most important problem, it sprouts like a seed, growing both a tree above ground and a deep root structure below, creating countless new problems. And so we see the same situation again and again: people surround the “problem tree” above ground, wasting lots of time and energy trying to find ways to solve perceived problems that wouldn't have existed at all if they made the right decision a long time ago. They don't even notice that the real problem is in the roots of the tree.

Another common yet surprising example can be found in most people’s perception of “success”. Most people see success as an end point , and this misunderstanding leads to countless new problems that could have been avoided if this one mistake had been avoided in the beginning. Success is hard to achieve if we see it as an end point, because we will imbue such a final goal with so many unrealistic hopes and fantasies that we will be unlikely to reach it. Even if some who take success as an end point are lucky enough to reach it, the process will make them abnormal. The craziness that follows success, and the result of that craziness, is actually the result of the mistaken belief from years before that success is an end point.

In fact, success is a new beginning. If you start a business, this is a beginning rather than an end. Each time your business raises money from venture capital, that is also a new beginning. Even if you go public, that’s still a new beginning rather than an end point, because you have to continue to help the company grow. In fact, the most tragic failures in life always come from perceiving a new beginning as an end point.

Investment is also one of these few essential decisions in life, but most people haven’t seriously thought about it, let alone made a decision. The investment arena is divided into two extremes -- it’s a binary world in which you’re either a 1 or a 0. Either you are extremely successful, or you are not extremely successful, and then you are mediocre like everyone else, which is basically equal to zero. In my view, the existence of this phenomenon is also related to the fact that most people fail to resolve the most important problem at the beginning.

So what’s the most important concept in the area of investment? Long-term.There are more scams in the investment world than in any other area. Why? Because people who have not deeply understood the important concept of long term are always confronting their “problem tree”. Each leaf on the tree is a perceived problem that they must solve, and each branch is something bigger that they need to think about. They ignore the roots underground, though, because they are too mysterious to understand. In fact, this tree should not even exist.

There is a huge gap between knowing and doing, and long-term practice is the only way to cross this gap. A strategy of regular investing is the simplest way to practice investing, as all you have to do is regularly purchase a set investment over the long term. However, simple itself doesn’t necessarily mean easy.

In Greek mythology, there is an island inhabited by the beautiful Sirens. Their incomparable appearance and voices caused passing sailers to lose their minds and crash into the rocks. Only two heroes were able to safely pass. The first was Orpheus, who played the lyre so beautifully that it drowned out the voices of the Sirens. The second was Odysseus, who used wax to plug his sailors’ ears and ordered them to tie him to the ship’s mast so that he could hear the Siren’s song that he knew he would be unable to resist.

The strategy of regular investing is correct, but the target investment must be chosen by each individual investor. In this book I will provide you the tools to make your own decision about what to invest in. I will do so by showing you what I’m regularly investing in, and explaining the reasoning behind that choice.

On Regular Investing is not only an open-source book, it’s also paired with BOX, the first digital asset ETF with no carry or management fees, which I designed. Regular investing is simple, but not necessarily easy, because it’s as if the boat we are sailing in is passing by the island of the Sirens. BOX is the boat, and those who are investing in BOX with us are the sailors who need to fill their ears with wax. The wax is continuous learning about regular investing, which I hope to provide in this book and in my classes. I suppose I am Odysseus, tying myself to the mast. Since there are no management fees, the way I make money is simple: like everyone else, I am in the same boat, regularly investing in BOX.

We should solve the most important problem at the very beginning, and not let it take root and grow into a problem tree that gives us a plethora of persistent troubles to deal with. This might be the single most important piece of wisdom in life.

Before long, you will discover that the strategy of regular investing is not only applicable to investing. Actually, it’s applicable to most areas of life, including study, work, and personal relationships. These are all areas in which the strategy should be used from the very beginning.

So again, the reason I am writing this book is because I hope that ten, twenty, or even thirty years from now its content will still be useful to many.

Investing is not easy, and successful investing is even harder. But just because something isn't easy doesn't mean there isn't a simple, direct, brutal and effective strategy that almost everyone can correctly master and deploy.

Regular investing is quite simple:

Regularly invest a set amount in a particular investment over a long period of time.

For example, every week (regularly) for the next five to ten years (a long period of time) invest 200 USD (a set amount) in BOX (a particular investment). Of course, you could change BOX to any investment that is worth investing in and holding over a long period of time, such as shares in Apple, Maotai, Coca-Cola, or an S&P 500 Index Fund.

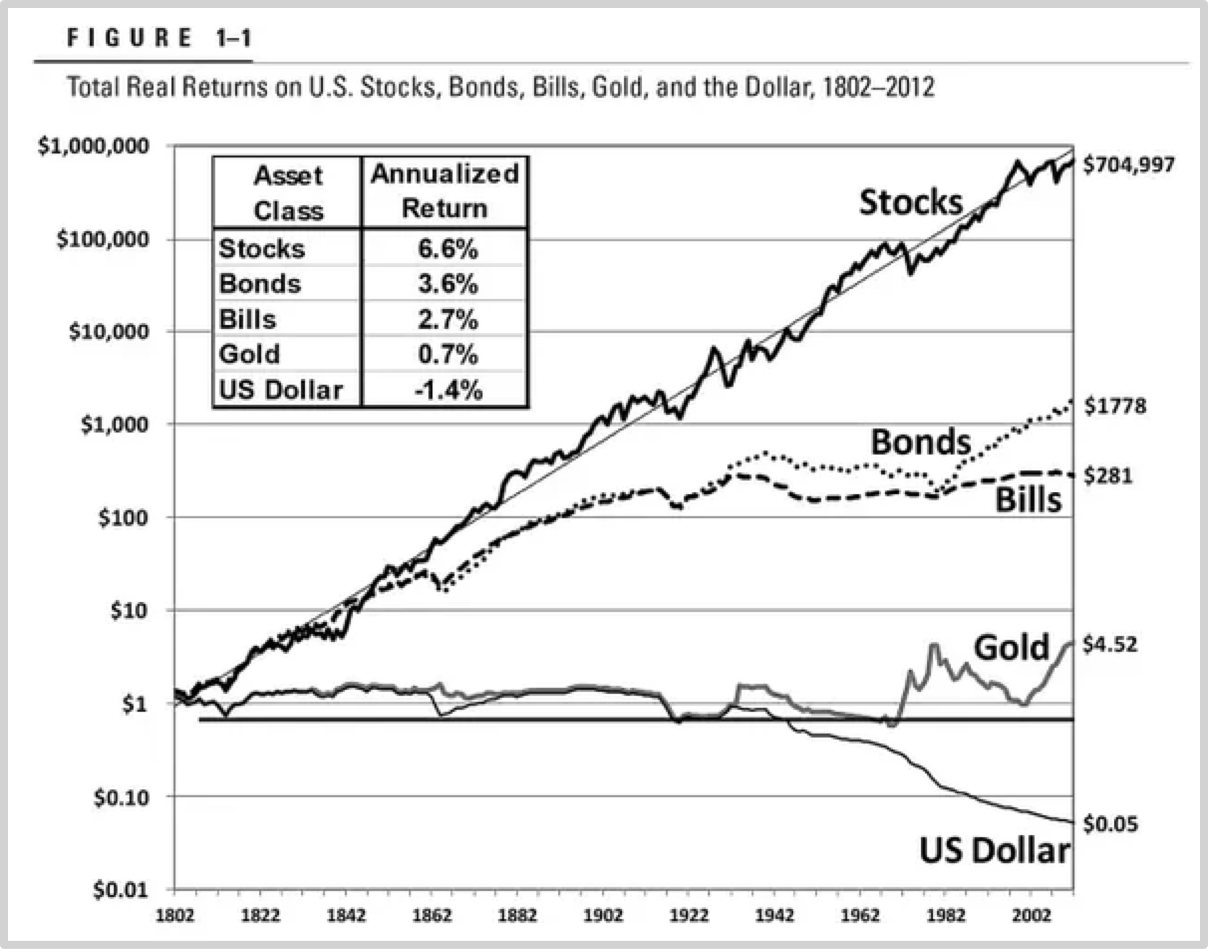

Is such a simple strategy really effective? The numbers don't lie.

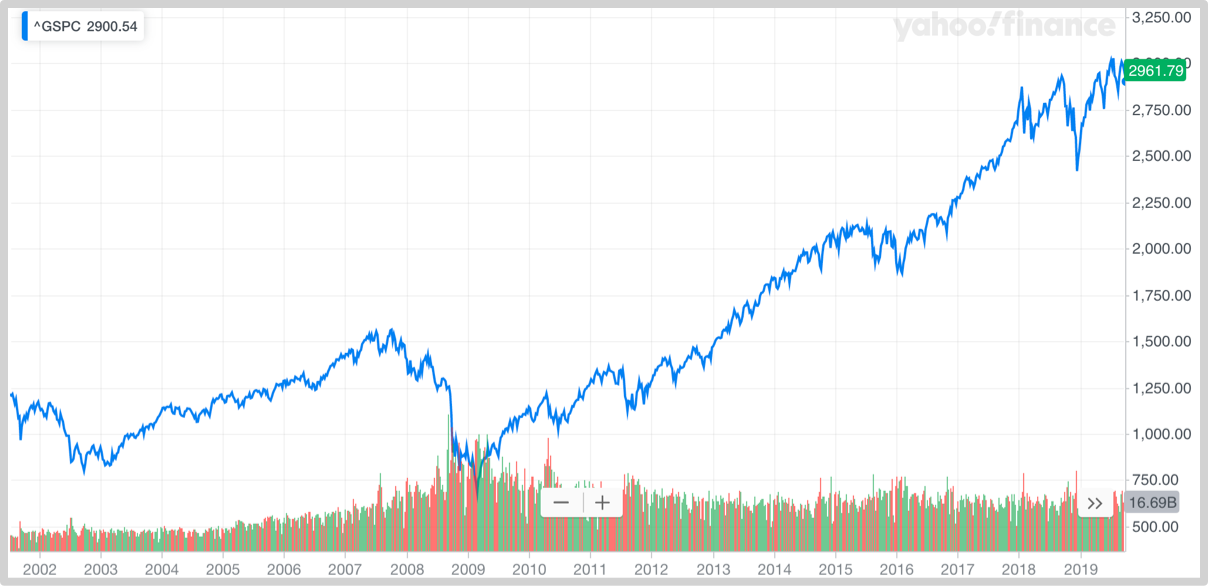

Suppose you started investing in the S&P 500 on October 8th, 2007. Knowing what we know now, that seems to be the worst time to enter the market, because what immediately followed was the 2008 financial crisis, and it was that day that the stock market began to crash. So if you started investing $1,000 USD per week on that day...

What would the result be? Back on October 8th, 2007, it would be really hard to say. But looking at it from today, more than a decade later, the answer is clear: the results were fantastic! We experienced a crash in the market from $1,561 to a low of $683, but we kept buying at that low price. Later, the market recovered, and by October of 2019 the S&P 500 had exceeded $2,960.

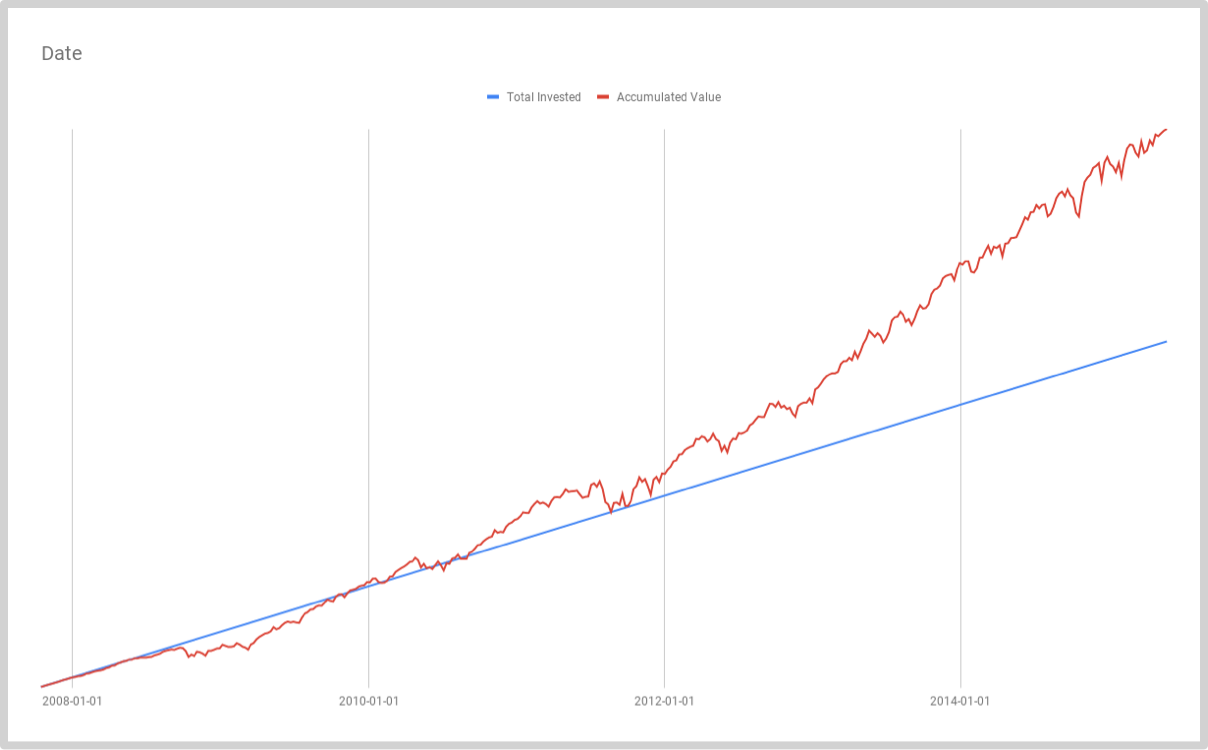

But this description is missing an important detail. The chart below shows the value of your total assets (the red line) and the value of your total investment (the blue line).

There is an extended period of time when your asset value drops below your total investments. But towards the end of 2009 the red line passes the blue line, and it almost never drops below it again, growing faster over time.

Note: The historical data in this chart is from Yahoo Finance (^GSPC), and the chart was created in Google Sheets; you can view the data and chart here.

The key point is that you entered the market at the worst time –- on October 8th, 2007, the S&P 500 was at $1,561, and it didn't return to this price until March 25th, 2013.

But if you take another look at the chart above, you'll see that the red line crosses the blue line for the first time in 2009. So while it took the S&P 500 286 weeks to return to its high, your strategy of regular investing began to see steadily positive returns after just 111 weeks. When you started to see positive returns, the S&P 500 was still 30% off its all-time high. When the S&P 500 finally returned to its high after 286 weeks, your strategy was already showing returns of 32.64%.

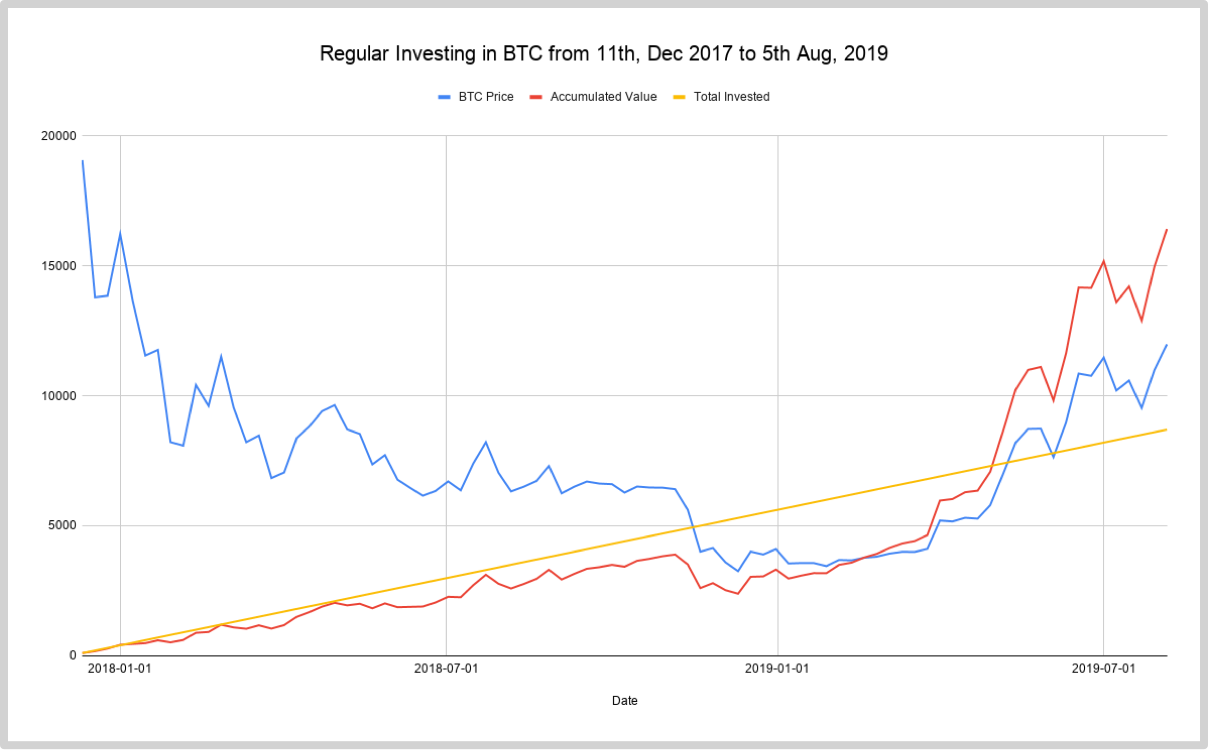

Let's take a look at an even more striking example. Suppose you started regularly investing in Bitcoin in December of 2017, when Bitcoin was at its all-time high of $19,800. Shortly afterwards, the price crashed, and it still hasn't returned to its all-time high. The chart below assumes you started regularly investing in Bitcoin on December 11th, 2017, and kept it up for 87 weeks.

Note: The historical data in this chart is from Yahoo Finance (Bitcoin USD), and the chart was created in Google Sheets; you can view the data and chart here.

Even though you entered the market at the worst time, your investment has still been profitable in USD terms, with the red line (your assets in USD terms) passing the blue line (your total investment in USD terms) on May 6th, 2019. If you invested $100 each week, by the 87th week you would have invested $8,700, but your Bitcoin would have been worth $16,417, for a gain of 88.71%. This is despite the fact that Bitcoin remained 62.85% of its all-time high, which was when you started investing.

This can seem really flabbergasting at first:

With regular investing, even if you start at what seems like the worst time, such as just before a market crash, your overall investment will become profitable before the market recovers.

Some fans of regular investing always emphasize a partially correct fact, which is that regular investing will effectively reduce your average cost. But the other side of the coin is that it also probably raises your average cost. It's obvious, isn't it? So these fans are using an incorrect reason to choose the correct strategy. But how long can an operating system with an error at the base level continue to run for?

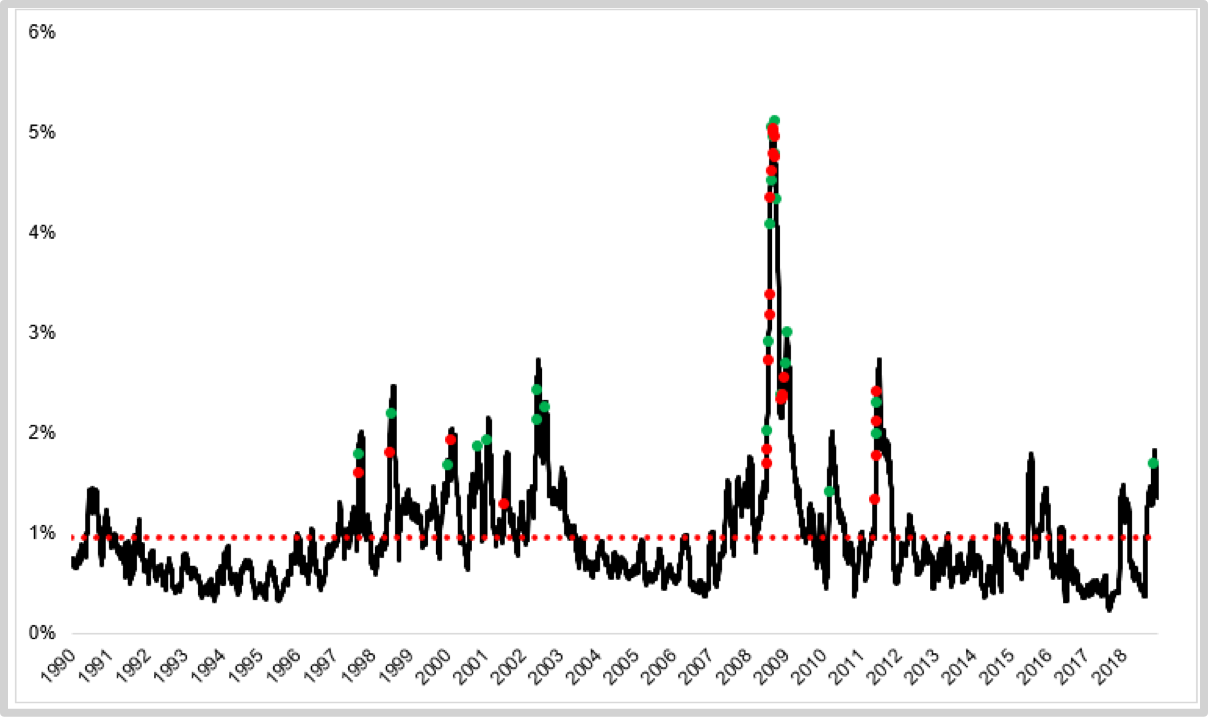

The reason why regular investing is effective is that it matches up with the following reality of markets:

Bear markets are much longer than bull markets.

For example, over the last one thousand days, the blockchain markets have had less than 150 days of a true bull market. The same phenomenon is true no matter which price chart you are looking at, whether it be the S&P 500, Apple, Google, Amazon, Facebook, Tencent, or Alibaba. Bear markets are always very long, and bull markets are always very short. Bull markets are so short that we call them bubbles, like the dotcom bubble at the end of the last century.

Once you understand this key point, you will understand the following;

With regular investing, your profits essentially all come from the bear market!

Most investors don't understand this, and it is the core reason why their investments are destined to fail. They want to make money quickly in the ephemeral bull market. It's really quite depressing: most of the "investors" who enter the market during a bull market are destined to lose their shirts, because before they realize it, the short bull market has ended, and the long bear market has begun. Regular investors, on the other hand, are slowly accumulating throughout the bear market.

In fact, the strategy of regular investing is not only applicable to trading markets, it's useful in almost all important areas of life, whether it be study, work or family. "Lifelong learning" is essentially a regular investing strategy, isn't it? If you could draw a "price curve" for an individual's learning, it would look a lot like the S&P 500. Even though it increases substantially over time, it goes through long periods of flat growth or even drops. Often when you are investing time in learning something it feels like you would be better off not learning it. The "bear market" is long, isn't it? This explains why so few people are able to become true lifelong learners. The reason is the same: everyone wants to make money quickly in the bull market and then leave.

Jeff Bezos once asked Warren Buffett, "Your investment thesis is so simple... Why doesn't everyone just copy you?" Buffett's reply was quite striking:

Because nobody wants to get rich slow.

The most important part of Buffett's strategy is to hold for the long term. He has said that "Our favorite holding period is forever." At its core, the reason why regular investing works is that it is the ideal version of a long-term holding strategy. Most of the time, even Buffett doesn't just buy a target all at once; he enters his position over time. Those who follow the regular investing strategy also continue to buy at regular intervals over the long term, and hold the asset throughout the process.

The core of the regular investing strategy is long-term holding. It's well recognized that the longer you hold the more likely you are to make a profit, but there is a key question we have to answer if we are to have a deeper discussion:

How long is "long-term"?

If we don't have an accurate answer to this question, we can't even really use the concept of "long-term". For any concept to be useful it must be clearly defined, and since we must combine concepts together, if we have multiple unclear concepts then the accuracy of our judgment will be severely impacted, just as multiplying 80% by itself five times will leave us with less than 33%. In the course of reading this book, you will encounter several concepts that must be used together, and they must be clearly and accurately defined in order to be useful.

Unlike most people, I have a fairly clear, accurate and useful definition of long-term:

Long-term means longer than two full market cycles.

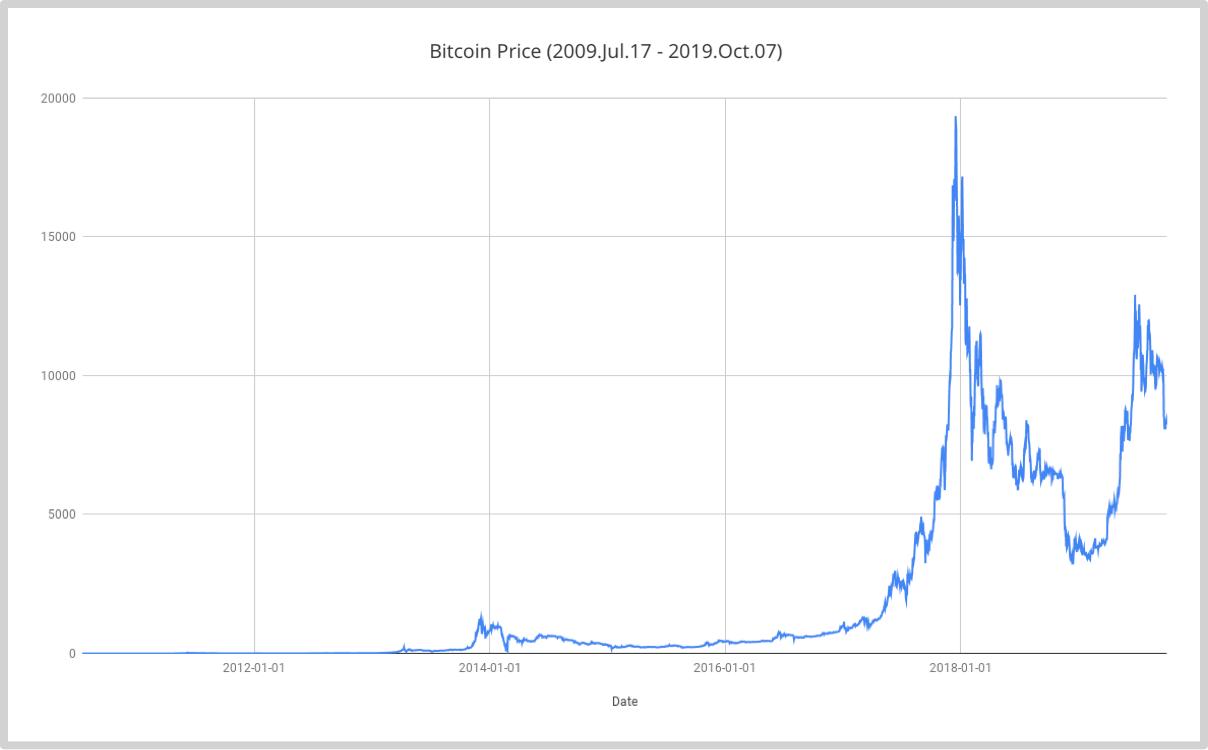

A clear and accurate definition of "long-term" thus depends on a clear and accurate definition of another concept: "market cycle". So what's a full market cycle? Let's use bitcoin's historical price chart as an example.

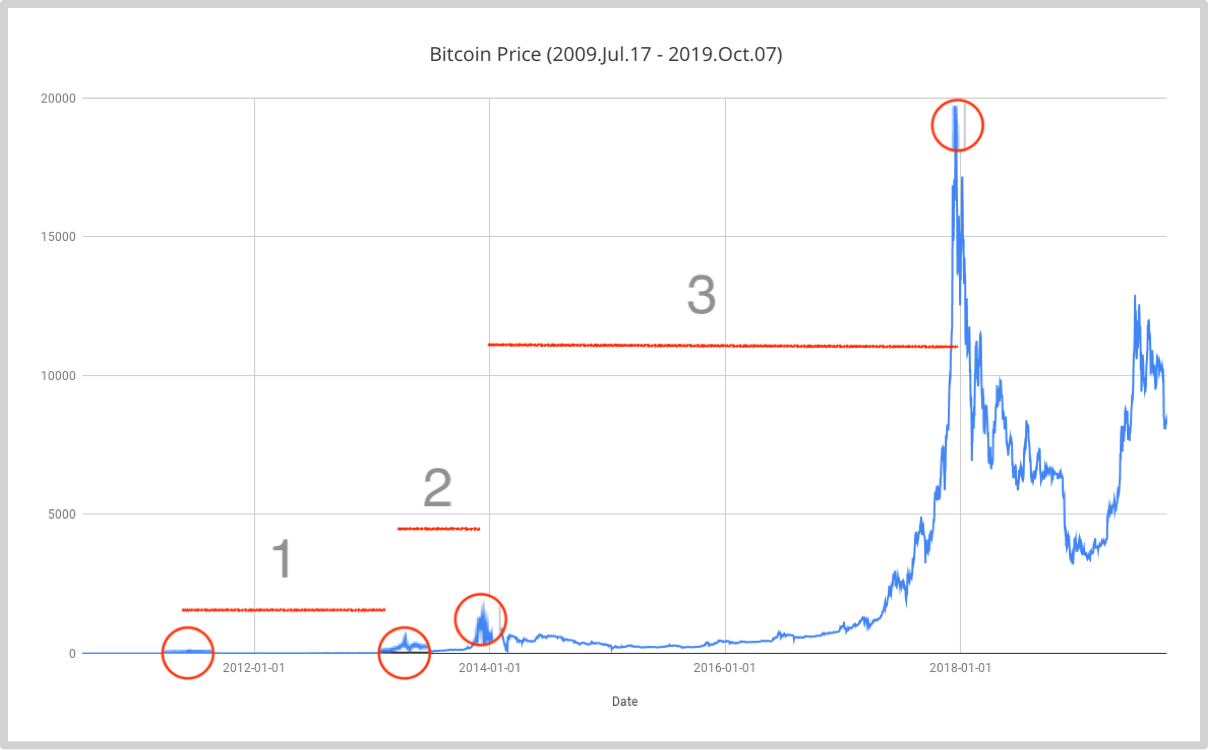

A full market cycle is composed of a period of falling price (Period B) and a period of rising price (Period A). In this chart we can see a full market cycle, with Period B beginning in December of 2013, when prices started falling, and Period A ending in December of 2017, when bitcoin reached its historical high.

How can you tell when a market cycle begins? Actually, we can only make this determination after the fact. Since short-term prices can rise and fall unpredictably, it's impossible to know when a high or low point for a given period has been reached. It's hard to know how long after the fact it will be before we can make the determination, but we can be sure that it will be long enough that it will not be useful for short-term trading decisions.

On the same chart, I have marked the three full market cycles that I have personally experienced with bitcoin. The first started around June 8th, 2011, at a price of $32, and ended on April 11th, 2013, at a price of $266; the second started at the end of the first and ended on December 19th, 2013, at a price of $1,280; the third started at the end of the second and ended on December 17th, 2017, at a price of $19,800. Actually, I have experienced more cycles than this, since I entered the bitcoin market two months before the June 2011 high of $32, and I have continued and will continue to hold Bitcoin since the December 2017 historical high of $19,800.

There are several details in this chart that are worth looking at closely. For example, we can clearly see that, as I mentioned earlier, bear markets are much, much longer than bull markets.

Why do we need to emphasize at least two market cycles? Because many people misunderstand trends. They see that today's price is higher than yesterday's, and that yesterday's price was higher than the day before, and they think they have identified an "upward trend". They then erroneously assume that tomorrow's price will be higher than today's. But it's actually impossible to judge a trend in the short term, even over the course of one entire cycle.

Only after two full cycles can we make an accurate judgment about whether a trend is more likely to be upward or downward.

Furthermore, please note the use of "more likely to be" in the sentence above. Even after two full cycles, we still cannot be 100% sure about the future trend based on historical data. At this point in time (October 2019), bitcoin's price has still not returned to its historical high, and we cannot be 100% sure that Bitcoin will ever exceed its historical high. We will only be able to make this determination after the fact –- long after the fact. In the end, from any point in time, we can only make investment decisions based on less than 100% certainty. Since the future is full of risk and unknown factors, we can only use terms such as "more likely". Actually, this is precisely why investing is so interesting.

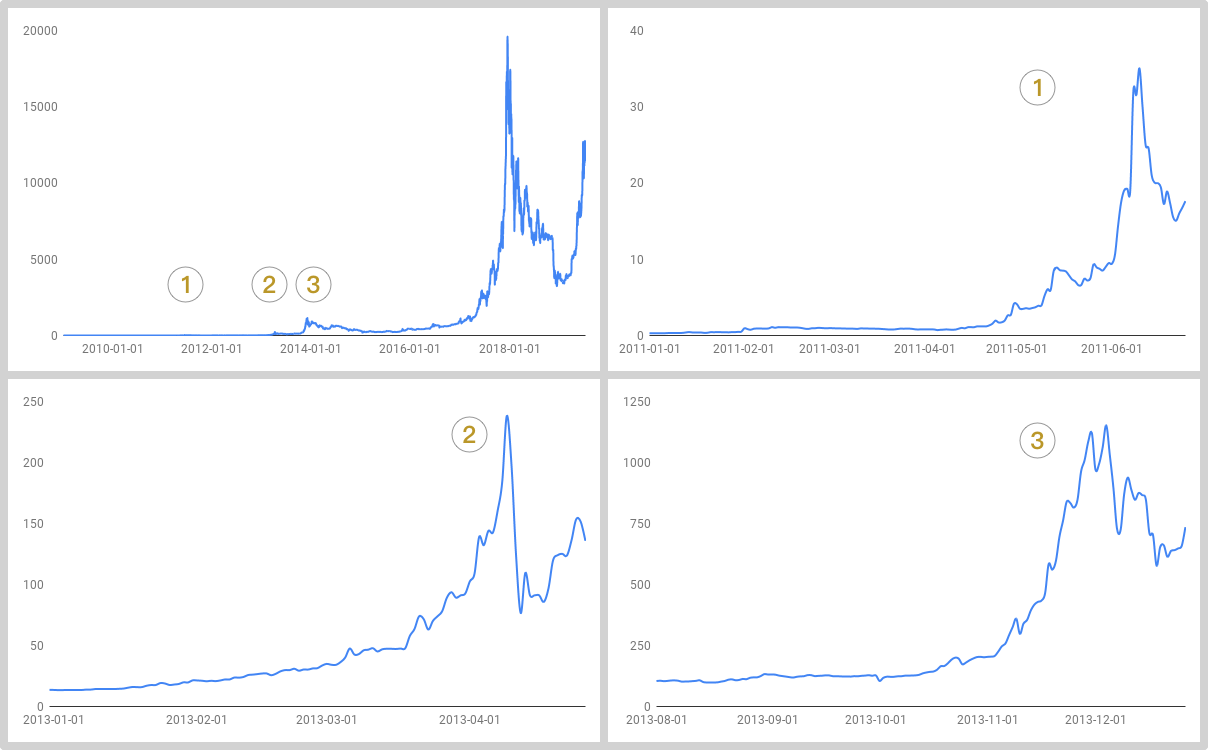

In the chart above, we can barely see the high reached in June of 2011. But if we separate each historical high into separate charts, we see that they look strikingly similar.

Each of these charts looks quite similar to the overall historical chart, which is to say that even as I am in the midst of my fourth full cycle, and even though I have made similar judgments based on "more likely" before, I still can't be completely sure this time. I still can only use "more likely" as the basis for my judgment. It's just that I've been quite lucky in that my previous three judgments based on "more likely" were proven to be correct.

Let's briefly summarize what we have discussed thus far:

- a period of rising or falling prices does not necessarily constitute a trend –- it's impossible to determine a trend over the short term;

- a period of falling prices (Period B) followed by a period of rising prices (Period A) constitutes a full cycle;

- we can take each historical high as the starting point for Period B of a full cycle;

- we can only determine the historical high of a period after the fact;

- it takes at least two full cycles to determine a trend;

- the best we can do is determine that a trend is more likely;

- an upward trend often results in a new historical high, but we can only determine the highest price of a cycle after the fact;

- long-term holding refers to holding for at least two full cycles, or through two bear markets and two bull markets.

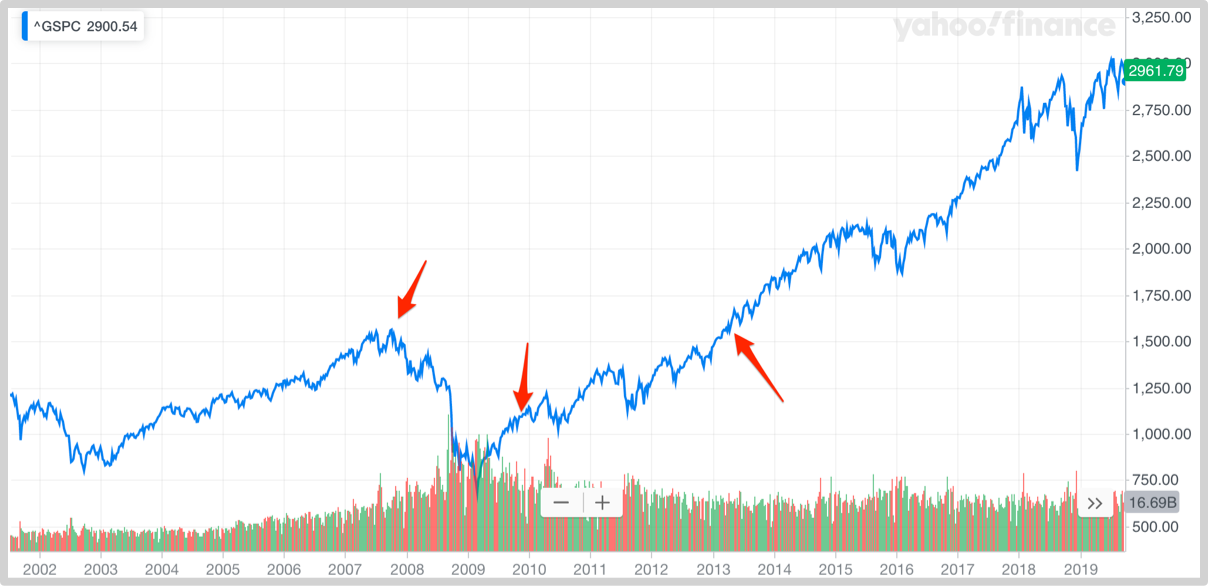

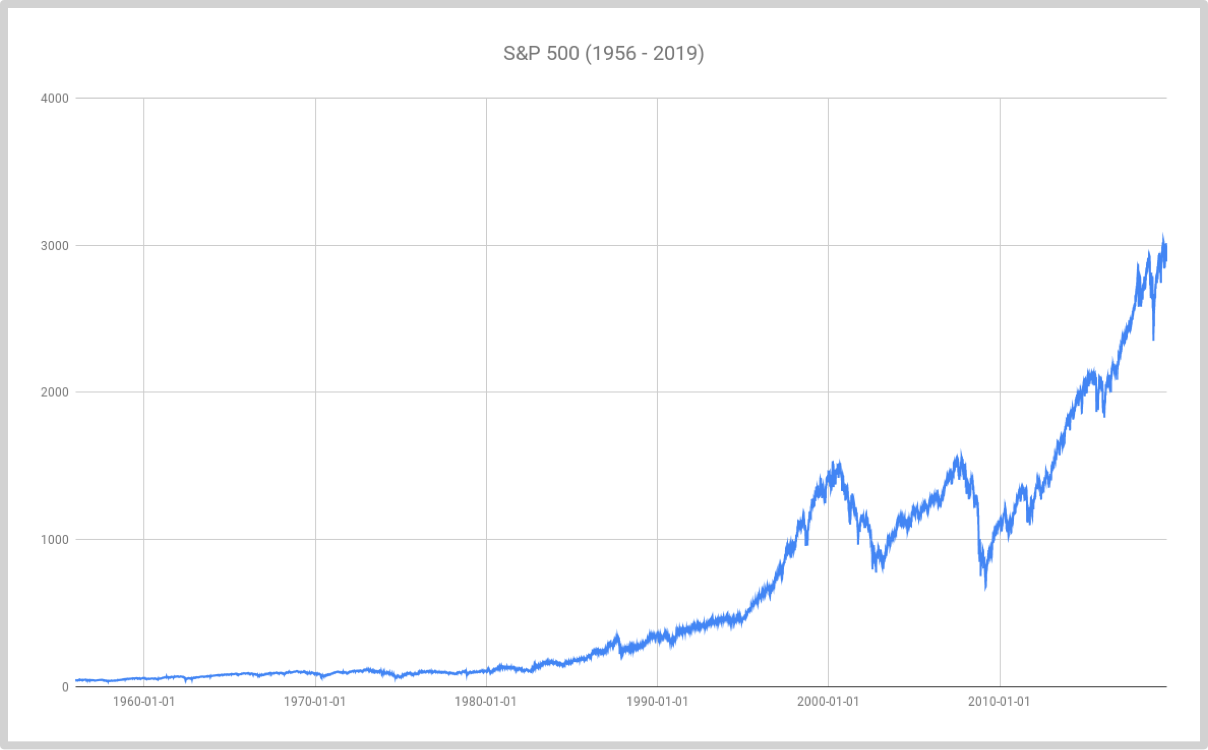

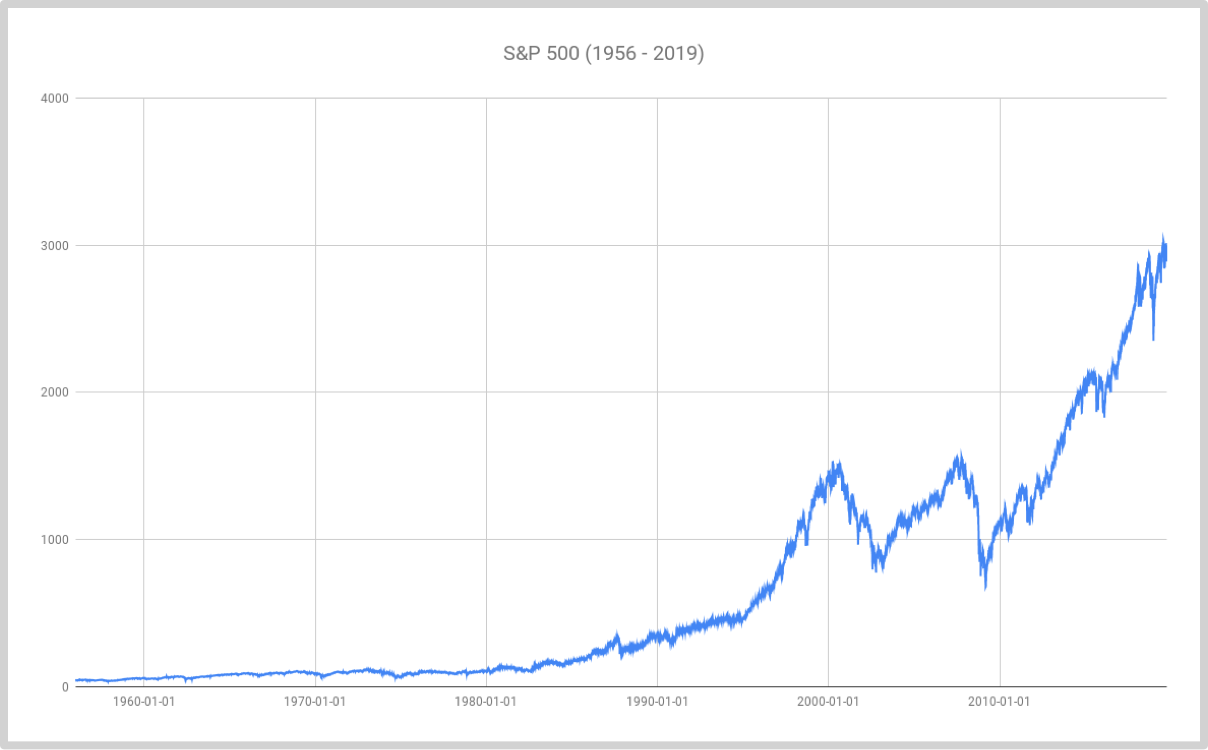

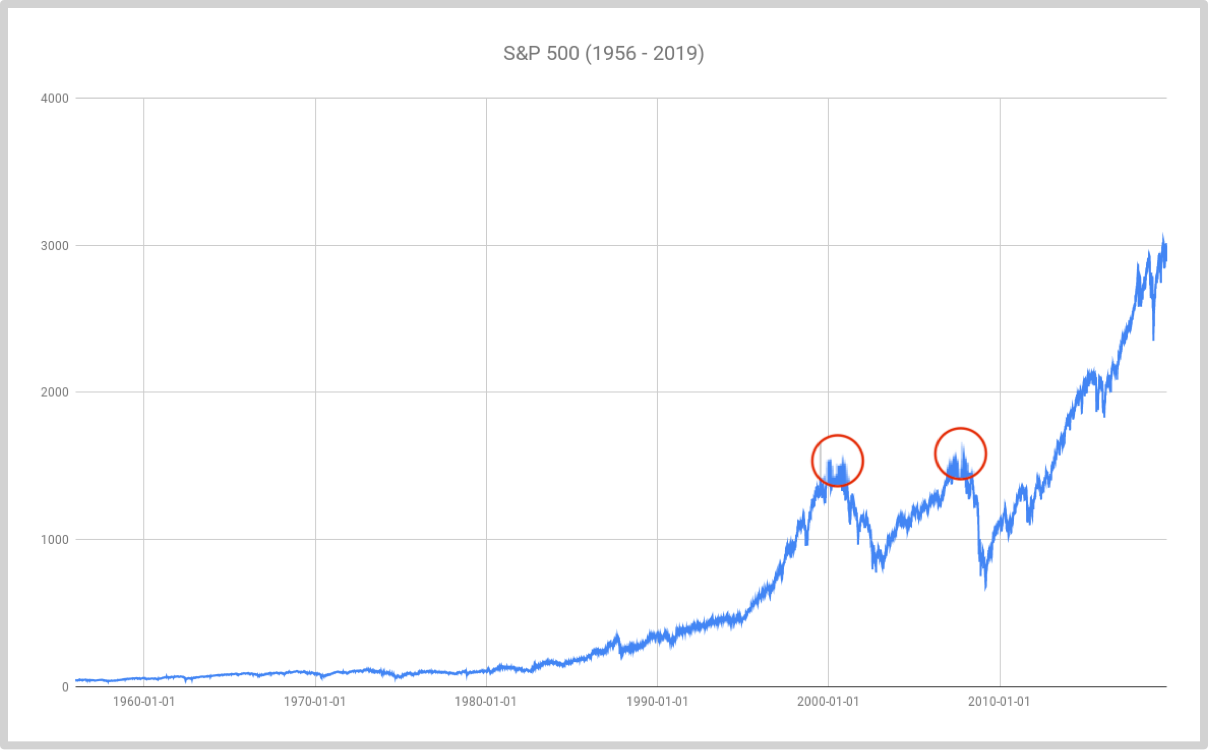

If we use this upgraded way of thinking to look at any price chart, we will get a completely different result than before. Below is the price chart for the S&P 500 from 1956 to 2019:

Note: The historical data in this chart is from Yahoo Finance (^GSPC), and the chart was created in Google Sheets; you can view the data and chart here.

There's an easy way to understand how economic cycles are shaped:

Economic cycles are shaped by participants in the economy coordinating well at some times and poorly at others.

When many parties -– and "many" here refers to so many that some parties don't even know of the existence of others -– are communicating more and more efficiently, the length of cycles will become shorter and shorter, even if fluctuations, which occur when parties are not coordinating well, may never be completely eliminated.

If we look at it from this perspective, we can easily understand why the Great Depression of the 1930s took so long to recover from (i.e., complete the cycle), yet the recovery from the Asian Financial Crisis of the 1990s only took a few years, and the recovery from the worldwide recession brought about by the US subprime crisis was even faster.

The reason is simple and easily understood:

The rapid flow of information makes worldwide cooperation easier and more seamless, so even though crises will continue to occur, recoveries are becoming more rapid.

This is also why blockchain assets see shorter fluctuation cycles. Over the past eight years I've often heard people use the halving of bitcoin's block reward every four years as a way to distinguish bitcoin's cycles. Maybe that was useful early on, but, now that Bitcoin is no longer the only valuable blockchain asset, using the block reward halving as a basis for determining cycles has slowly lost significance.

I think the reason why blockchain asset markets have shorter cycles than stock markets is due to the fact that the players in the market are clearly coordinating more efficiently. We can see this just by looking at the number of trading markets. There are only a few influential stock markets, but there are thousands of markets on which to trade blockchain assets, and trading continues 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. This type of coordination greatly exceeds the coordination of traditional securities markets.

It is truly great news:

Cycles are getting shorter and shorter.

Cycles in stock markets have already shrunk from decades to less than a decade, and they continue to shrink. Blockchain market cycles are already shorter, and they are also shrinking.

In my view, long-term doesn't mean forever, but is a clearly defined concept of two or more full market cycles. In the stock market, two full market cycles will take about ten to fifteen years; in the blockchain market, two full market cycles will take six to eight years. Either way, they are both futures worth waiting on, right?

For most people, money only has one use: consumption. Sadly, this is the basic reason why most people are unable to achieve financial independence. They have almost never seriously thought about money's second and much more important use: investment.

For those who only know how to consume and don't understand investment, it's hard to escape their original fate. They can only make money by selling their time, and the amount of time that they can sell is extremely limited –- we have much less time than we think.

There is a set of data that can help us understand how little time we actually have to sell. If we take an average lifespan of 78 years...

- We sleep for 28.3 years;

- We work for only 10.5 years (this is the time that most people are able to sell);

- We spend 9 years watching TV, playing video games, and using social networks;

- We spend 6 years doing chores;

- We spend 4 years eating and drinking;

- We only spend 3.5 years on education;

- We spend 2.5 years grooming;

- We spend 2.5 years shopping;

- We spend 1.5 years on child care;

- We spend 1.3 years commuting.

According to these estimates, we only have nine years left to allocate as we please! The amount of time we have to sell is our work time of 10.5 years plus the nine years we spend on leisure. Even if we allocate all of those 9 years to paid work, we still haven't even doubled the time we have to sell. And we still sleep for longer than the time we have available to sell. Sleep is expensive!

When I was young, I worked very hard just like everyone else.

Upon graduating from college I started working in sales, and there were weeks in which I spent six nights sleeping on a train. I'd get off the train in the morning, find a place to shower and change clothes, spend the day running sales trainings, and then hop back on a train at night to head to the next city, where I'd start all over again.

People who have known me for a long time know that I don't have holidays. This is because, shortly after I graduated from college in 1995, I realized that there are so many holidays! In China, out of 365 days in the year, there are 115 legal holidays (including weekends)! That means we spend a third of the year resting! Something didn't seem right. Later I realized that "legal" holidays are established to limit corporations. If a corporation forces someone to work on a holiday without extra pay, it's illegal, but there's no limit on what an individual can do. There's no law at all that says, "today is a legal holiday, so if you don't rest you're breaking the law!" So, from that point on, I decided that I would have nothing to do with legal holidays. It's been 24 years since 1995, and I have done my best to ignore weekends and holidays. I just do what I want to each day! I've published a lot of books, and most of them have been written by myself over the Chinese New Year while everyone else was on vacation. I've worked very hard, haven't I?

About ten years ago, I suddenly realized what a waste of time it was to worry about hairstyles. Everybody spends a couple of hours to get their hair cut each time, and they often end up waiting for a long time at the barber. So I decided that I would cut my own hair. A good Phillips trimmer only costs about $50, and you can use it for many years. So I've had the same hairstyle for the last decade -- a three millimeter buzzcut. It's easy to just use the trimmer every few days for a few minutes before I shower. Can you see how hard I work to save time?

The numbers, however, are rather disappointing. By not having a holiday in 24 years, how much time have I freed up to sell? Even if I don't rest on holidays, I'm only likely to have four hours of effective work every day. If you've worked for yourself, you know that the amount of truly effective work time you can have in one day is quite limited. So how much effective work time have I created by having no holidays over the past 24 years?

24 x 115 x 4 = 11,040

Just over 10,000 hours. So how many years is that?

11,040 ÷ (365 x 24) = 1.26

You see? I've been so hard on myself, and all for what? All for merely 14% more time than other people who work very hard but still take holidays. And what about the decision I made 10 years ago to cut my own hair? How much time have I saved with that? If you cut your hair once a month, and it takes 1.5 hours, that's 18 hours per year. Over ten years, that's 180 hours. You see? I took such good care of my time and was so hard on myself, but I only saved 7.5 days! All that effort, and I only end up with 0.228% more time than everybody else!

Frank H. Knight, one of the most influential economists of the 20th century, has a famous postulation:

Ownership of personal or material productive capacity is based upon a complex mixture of inheritance, luck, and effort, probably in that order of relative importance.

Of course, this doesn't mean that effort isn't important. Some measure of success can be achieved through effort, but huge success depends on luck, and we all know that we can't control luck (or inheritance!). The problem, as we have seen, is that we have a limited amount of time that we can sell, so effort is of the least relative importance.

However, it's different if we use money to make money. The core of investing is using money to make money, and money doesn't rest –- as long as you make the right investment, it works for you 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. How can your sweat and tears compete with that?

The reason we admire Warren Buffett so much is due to the following fact:

Warren Buffett was born in 1930 and bought his first stock when he was 11. It's now 2019, so he has been investing for 78 years!

78 years! The average person only lives 78 years, and they only have an extra nine years to allocate. But Buffett's money has already been working hard for him 24 hours a day, 365 days a year, for 78 years!

It's not hard to understand what a huge difference investing can make.

It's an undeniable fact that most people don't invest. And they have an answer as to why they don't invest:

I don't have any money to invest!

This is a frustratingly common misunderstanding. In fact, in addition to investing money, we have another resource that we can invest -- time.

It's not just non-investors who forget this. Even the few who do invest don't realize that, in addition to money, their time is also an investible asset. They haven't thought about how important time is, and how strong an influence it has over us.

Warren Buffett is undoubtably the most commonly-researched investor in the world, and you'll find his name in most books on investment, this one included. There's no way around it, as most of what he says is correct, and, perhaps more importantly, he's been so successful that most of what he says on the topic must be correct, and most people can't help but agree with him.

Buffett is not just successful, he's also always very open in sharing his thoughts and ideas. The problem is, he's told us everything that we need to do, so why can't we just go do it? Even though the difference between knowing and doing is the difference between monkeys and humans, there is a yet more important reason:

Warren Buffett has a zero cost of capital!

Berkshire Hathaway's key turning point in its early years came in 1967, when it bought National Indemnity Company and entered the insurance industry. Remember, Berkshire was a textile company that Buffett took control of in a fit of anger, and he regretted getting into the textile industry for many years. It wasn't until 1985 that Berkshire finally exited the textile business, nearly 20 years after Buffett took control in 1964.

But after entering the insurance market in 1967, Berkshire became an investing machine. The reason was simple: Buffett not only had a huge amount to invest, the funds also came at zero cost, and they could be used almost indefinitely. This was a huge relative advantage over all other investors in the world.

Books about Buffett talk about his incredible returns, and they treat his investment principles as the Bible. Even a casual statement at Berkshire's annual meeting can be taken as law. But 99.99% of investors will never have access to massive amounts of free capital to invest over an unlimited term, and that's a big reason why Buffett has been extraodinarily successful.

Regular investors are different. They may not have that much money, but they are investing more than just money. Since they are continuously investing over the long term,

they are also using time to invest.

The reason I have been able to hold bitcoin and other blockchain assets over the long term is not, as many people think, because I have "faith". In fact, faith doesn't require logic, and can't depend on logic, because if it did depend on logic, all faith would be shaken in the end.

The core reason I have been able to hold these assets is that I have the ability to continuously make money over the long term outside of the market, because I have upgraded my personal business model.

The vast majority of people can only sell their time once, but, after upgrading, I can sell my time multiple times. For instance, by writing books or teaching online.

Even though there is a ceiling on this business model, it has allowed me to not be tied down by daily expenses. It also allows me to always have money to use for investment that, despite being limited in amount, has no cost, is constantly flowing in, and can be invested over an unlimited term. Without this, all of my achievements in the investment space would have been impossible. So my regular investment into blockchain assets is not just money, but all of the effective time that I have spent working, and the sustainable income that has come from repeatedly selling this time.

So regular investing is something that people with ambition but limited resources can do, and it is something that only this type of person can do. When Buffett purchased a controlling stake in Berkshire Hathaway, he was already not a poor man. After purchasing National Indemnity Company and entering the insurance industry, almost all of his investments were long-term buy-and-hold investments. Buffett didn't need a strategy of regular investing. Or, to put it more precisely, he didn't need to improve upon his buy-and-hold strategy. The simplest strategy in the world was already enough for him.

As for other fund managers, they are even less able to pursue a regular investing strategy, primarily because 99.99% of fund managers (or, everyone except Buffett) have a limited term for their capital. For some it may be ten years, for others it may be three to five years, but no matter how long it is it's still a limit, and that entails great risk. In the investment world it's rare to have a middle ground -- it's either a 1 or a 0. If capital has a term the risk is 1, if it doesn't the risk is 0, and there is no 0.2 or 0.8. Lots of people don't understand this, so they line up like lemmings to take risks and end up falling off a cliff. The riskiest job in the world is President of South Korea, and right after that is the fund manager who guarantees immediate redemption of capital.

To put it another way, most "professional investors" don't have the ability to do regular investing, because they are not managing their own money, and their funds have a deadline after which they need to be returned. Once it's time to settle the funds, it doesn't matter if it's a bull market or a bear market, it's still time to settle, so how can you be sure of your earnings? Most people have never thought about how a fund's success is not dependent on the manager's acumen and strategy but instead dependent on the time the fund was established. Funds that are established at the end of Period B and the beginning of Period A are quite likely to succeed, because during that period you can make money investing in almost anything. The problem is that is the time at which investors are the most scared and circumspect, so it's hard to raise money. The easiest time to raise money is at the end of Period A, when everyone has gone crazy in the bull market. But if they raise money at that time, and the money has a term, it's going to be very difficult to succeed.

Selling one bit of your time more than once is an upgrade of your personal business model. It's such an important upgrade that it is hard for anyone to free themselves from the shackles of increasing daily expenses without it. At first you only have to take care of yourself; then you have to take care of your spouse; then you have to take care of your children and even your parents. Most people are defeated by these basic life expenses. An individual must make enough money to cover these expenses, which first increase and then may level out or even decrease later in life, before they can have money left over to practice regular investing. If you don't upgrade your personal business model, it's hard to have any money left over.

As I see it, regular investing requires a trifecta of successful personal business model upgrades:

- from selling your time once to selling the same time multiple times;

- from only using money to consume to using money to make money (starting to invest);

- from just investing money to also investing time.

Even more importantly, a strategy of regular investing systematically reduces risk.

We're always trying to find ways to improve our strategies. Everyone wants the strategies that they use to be as good as possible. When it comes to regular investing, though,

any efforts to improve the strategy of regular investing are futile.

From the establishment of the BOX Regular Investing Practice Group in late July of 2019, to October 9th, 2019, 3261 members have joined. After understanding the essence of the regular investing strategy, the group members know that most of the profit from regular investing comes from the long bear market. Because they have a different way of thinking, they now have a completely opposite take on the same world. Each time the price drops, they don't feel disappointment and fear, they feel happy, and even excited, because they can buy more at a cheaper price. Their decisions are the opposite of the outside world.

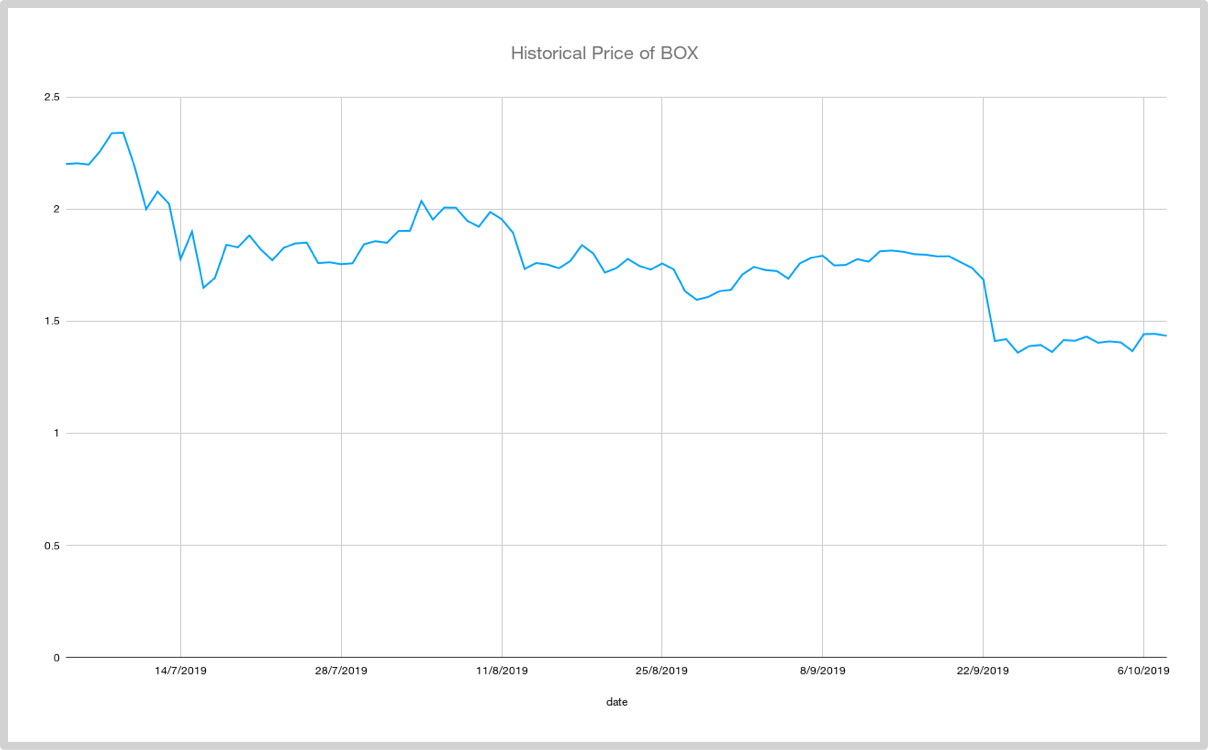

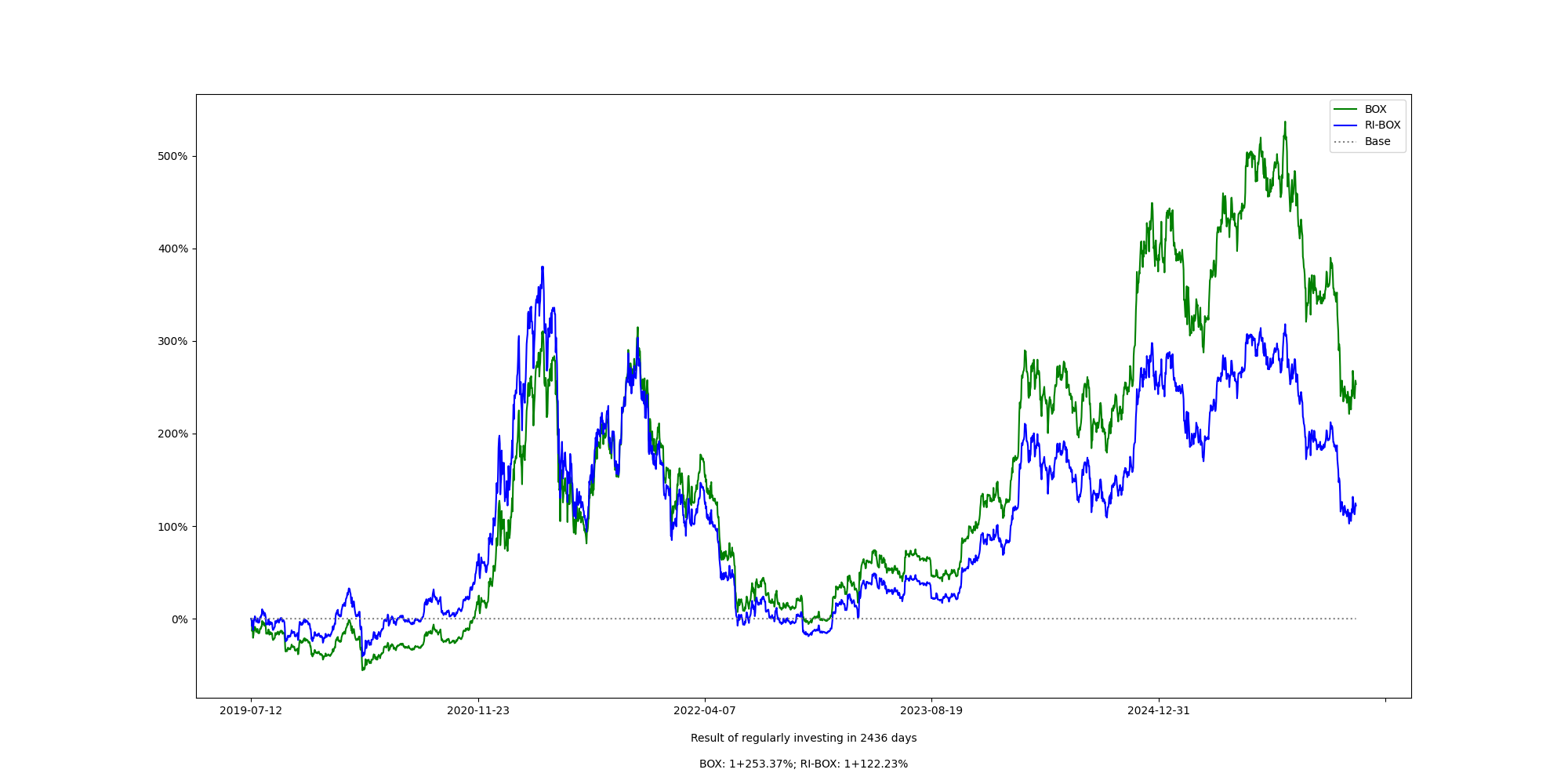

Below is the historical price of BOX over the past few months:

The chart below adds the daily amount of newly-circulating BOX, which is the amount invested in BOX each day. To make the chart easier to read, the amount of newly-circulating BOX has been divided by 100,000:

Note 1: The charts were created with Google Sheets, and you can view the charts and data here.

Note 2: The amount of newly-circulating BOX on September 2nd, 2019, was 221,010, but it really shouldn't count, because I alone bought 180,621 BOX on that day. I'm an old hand at regular investing, so of course I don't pay attention to daily fluctuations in price.

We can see that each time there is a large drop in price the amount of newly-circulating BOX greatly increases. The clearest example is found on the three days from September 25th to September 27th, which saw newly-circulating BOX of 214,048, 114,240, and 114,505, respectively, with September 25th showing an increase of five times the normal amount!

It's also clear from this data that people's reactions are late, because the drop in price actually happened several days earlier on September 22nd, when the price dropped from $1.68 to $1.41. As we can see in the chart, the increase in the amount of new BOX purchased always came days after the drop in price.

Furthermore, the group members had listened to my classes, in which I repeatedly emphasized the following:

Any efforts to improve the strategy of regular investing are futile.

Yet many of them still couldn't resist being driven by this simple thought: wouldn't it be better if I bought a little more when the price drops?

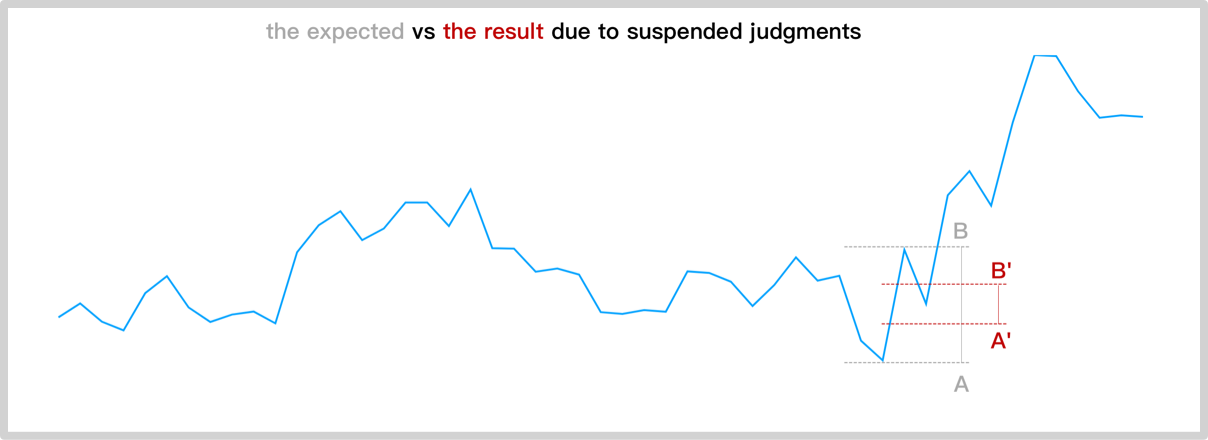

Let's discuss why this "improvement" to the strategy of regular investing isn't actually an improvement at all. First of all, each time we use the current price as a reason for making a decision, we are always actually making the decision after the fact. Even more importantly, we are neglecting an important fact: the short-term direction of the price after we make our decision is an independent event, and not tied to the prior change in price. After we buy, the price could go up, go down, or stay the same -- we don't know!

Someone who increased their investment amount in July after a price drop would have discovered in September that their "improvement" to the strategy was useless and actually cost them money, because the increased investment in July actually ended up increasing their average cost.

Whether or not an investor has a clear grasp of statistical probability is the factor that has the greatest influence on the accuracy of their decisions. Sadly, too many people don't pay enough attention to this basic knowledge, and they have no idea that this lack of knowledge causes them so much trouble and grief.

A person who understands statistical probability couldn't help but laugh at the following phenomenon:

Some people, lacking basic knowledge of statistical probability, try their best to prove on which day of the week prices are lowest.

Someone made a chart, and did some programming in Python, to support the following conclusion:

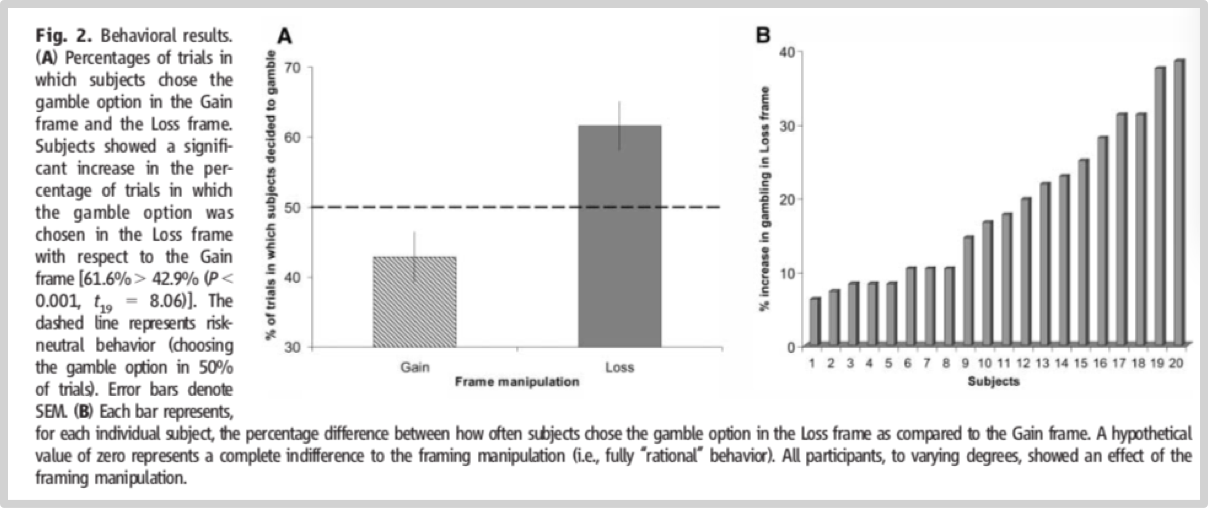

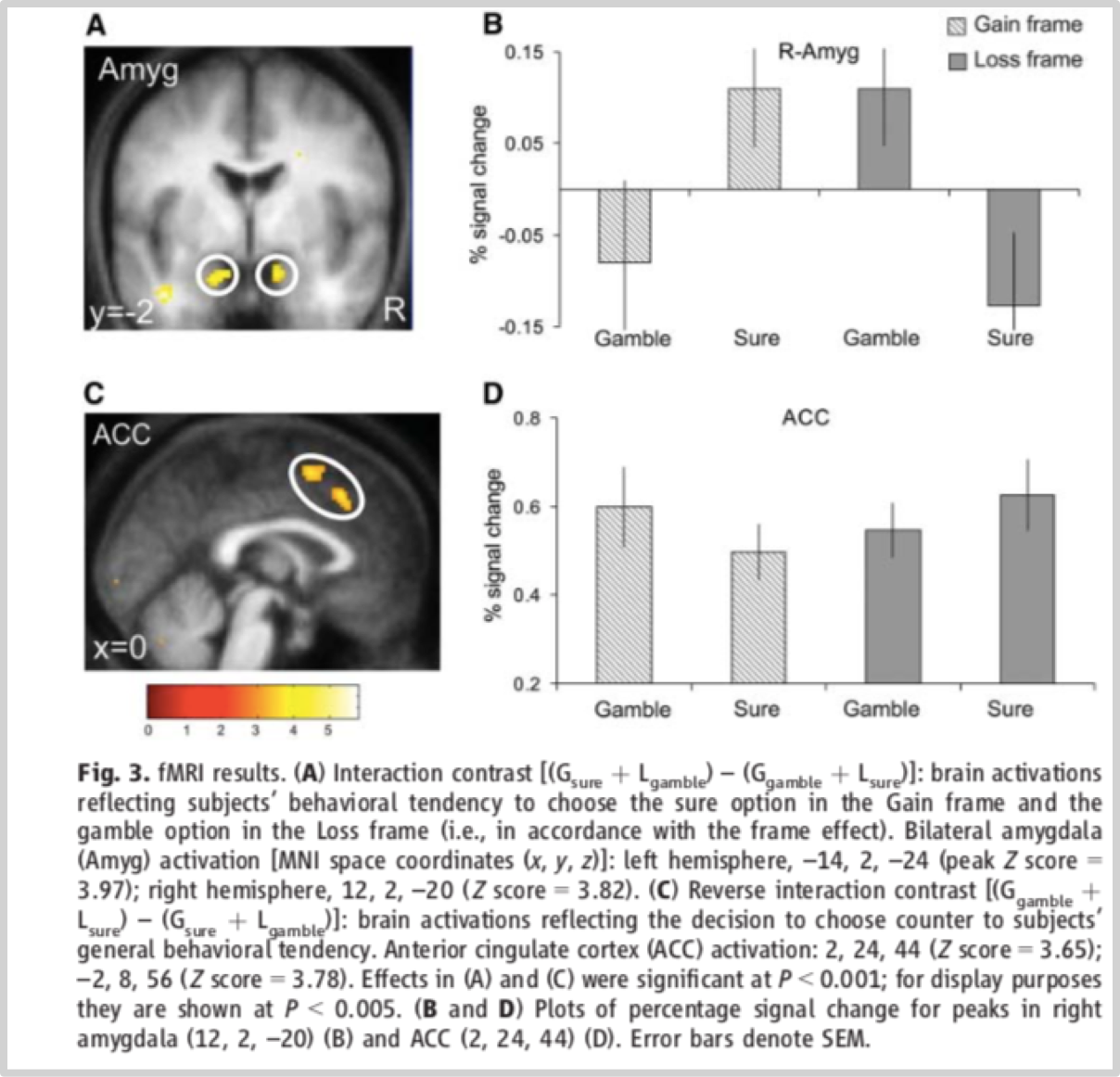

After analyzing every 350-day period of weekly regular investing in bitcoin over the 900-day period from July 17th, 2010, to January 2nd, 2013, the following conclusions have been reached:

Investing on Monday performed 1.2% better than the average of the other days. Furthermore, it is best to avoid Sunday, as Sunday performed 0.8% worse than average, perhaps because people have more time on Sunday, or perhaps because they feel more optimistic on Sunday.

Are these sorts of conclusions meaningful? It's basically impossible to use logic to convince people who don't understand the independence of random events, but in an article written in 1984, Warren Buffett gave a fun and yet deep example that might help:

I would like you to imagine a national coin-flipping contest. Let’s assume we get 225 million Americans up tomorrow morning and we ask them all to wager a dollar. They go out in the morning at sunrise, and they all call the flip of a coin. If they call correctly, they win a dollar from those who called wrong. Each day the losers drop out, and on the subsequent day the stakes build as all previous winnings are put on the line. After ten flips on ten mornings, there will be approximately 220,000 people in the United States who have correctly called ten flips in a row. They each will have won a little over $1,000.

Now this group will probably start getting a little puffed up about this, human nature being what it is. They may try to be modest, but at cocktail parties they will occasionally admit to attractive members of the opposite sex what their technique is, and what marvelous insights they bring to the field of flipping.

Assuming that the winners are getting the appropriate rewards from the losers, in another ten days we will have 215 people who have successfully called their coin flips 20 times in a row and who, by this exercise, each have turned one dollar into a little over $1 million. $225 million would have been lost, $225 million would have been won.

By then, this group will really lose their heads. They will probably write books on “How I turned a Dollar into a Million in Twenty Days Working Thirty Seconds a Morning.” Worse yet, they’ll probably start jetting around the country attending seminars on efficient coin-flipping and tackling skeptical professors with, “If it can’t be done, why are there 215 of us?”

In addition to not fitting our basic understanding of statistical probability, another reason why "invest on Monday and not Sunday" is unlikely to work is the following:

If it is really effective, then everybody will start doing it, and then it will no longer be effective.

Regular investing is simple, direct, brutal and effective. However, in addition to depending on the ability of the practitioner to earn money outside of the market, it depends even more on the selection of a quality investment target. If a mistake is made in the selection of the target, the result over the long term will be terrible.

It's important to note that what we are discussing is "how regular investors should choose an investment target", and not "how investors should choose the correct investment target". The former is a subset of the latter, and actually only has one additional condition:

Is it worth holding over the long term?

In the investment world, the Greet letter alpha (α) is used to refer to returns that exceed overall market returns. The goal of regular investors when choosing their investment target is to create alpha. They won't sell before at least two full market cycles have passed, because to do so would be to waste all of their previous efforts. All they do is buy, so they won't know for a long time whether or not their alpha is positive or negative.

The hardest question for those just entering the market is this:

Which one should I pick?

How can someone who doesn't even know what their criteria should be make a choice? How can someone who can only see the superficial and not the true nature of something make a correct choice about what to hold over the long term without wavering? There is a simple, direct, brutal and effective strategy that is also free:

Blindly follow the advice of truly successful investors who have shown excellent returns over the long term.

"Blindly follow" sounds extremely terrifying, but we actually can blindly follow the advice of truly successful investors who have shown excellent returns over the long term (please notice the key term: "long term"), because in the investment world there is an amazing phenomenon:

The more long-term successful experience investors have, the more open they are.

Warren Buffett started writing public letters to investors a long time ago, and later on he continued to share his investing ideas and decision-making process on television and through other media. Starting in 1964, Buffett has written a public letter to investors each year. As of 2019, he has been writing them for 54 years! Ever since 1973, he and Charlie Munger have held freewheeling Q&A sessions at yearly shareholder meetings. In 2019, the 46th year, a record 16,200 people attended, not including people watching online around the world.

Berkshire Hathaway's shareholder letters from 1977 to 2018 are available here:

http://www.berkshirehathaway.com/letters/letters.html CNBC's website has a special section called the "Warren Buffet Archive": https://buffett.cnbc.com/warren-buffett-archive/

Warren Buffett's mentor, Benjamin Graham, was also someone who shared without reservation. In addition to teaching investing classes, he wrote several books, most notably Security Analysis (1934) and The Intelligent Investor (1949). Warren Buffett read The Intelligent Investor when he was 19, and he became a fan of Benjamin Graham. One Saturday in 1951, while in the library of Columbia Business School, Buffett learned that Benjamin Graham was Chairman of GEICO, and he immediately decided to pay a visit to the company's office. Many years later, in an interview with Forbes, Buffett recalled that the investment he made in GEICO at the age of 20 was one of the investments he was most proud of.

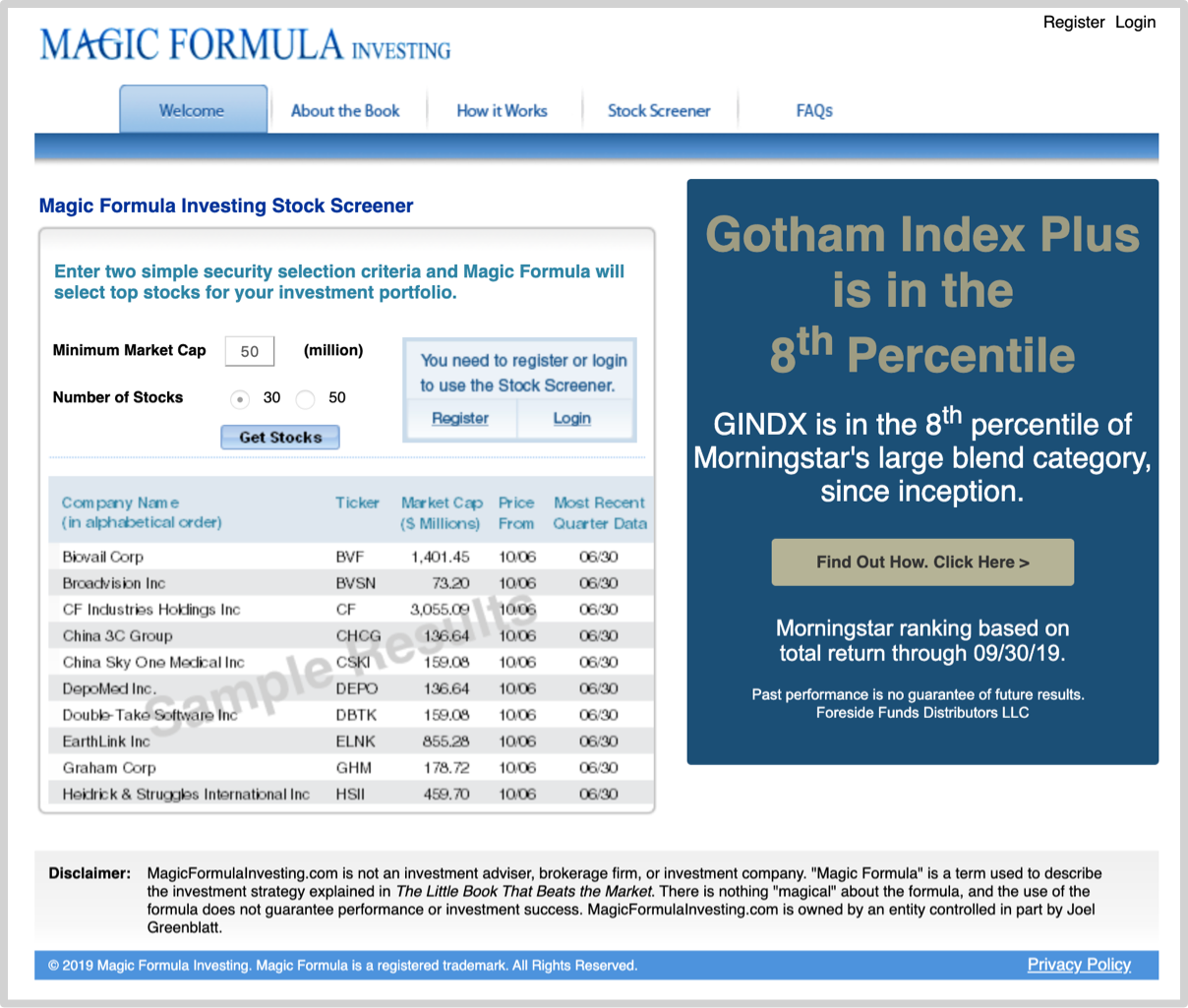

Joel Greenblatt's investing returns are perhaps even more impressive than Warren Buffet's -- from 1985 to 2006, his annual compounded returns exceeded 40%! Having been successful over the long term, Joel Greenblatt is also quite willing to openly share. He has published three books, namely You Can Be a Stock Market Genius (1999), The Little Book That Still Beats the Markets (2010), and The Big Secret for the Small Investor (2011). He is so down to earth that his standard for writing the books was that his teenage children could understand them.

Greenblatt didn't just share his ideas in his books, he also made a website, Magic Formula Investing, that allows investors to use his ideas to build their own portfolios. All you have to do is enter a few parameters and the site will give you a ready-to-go portfolio based on the "Magic Forumula".

Ray Dalio, the founder of Bridgewater, is yet another investor who has been successful over the long term and is willing to share his ideas. Long before his book, Principles, was officially published in 2017, he released a version for free online. In 2019, he even released an app called Principles in Action, which helps readers put the principles in his book into practice.

In the investing sphere, one must use money, time and action to create real results, and everyone is either a 0 or a 1. Investors who can successfully produce returns over the long term are 1s, and the rest are 0s, including those so-called experts who spend all of their time yelling through the television or other media but have no skin in the game. Investors like Warren Buffett, Joel Greenblatt and Ray Dalio don't need to spend all day screaming through the television, because their ideas have already been clearly expressed through their books, writings and speeches.

Perhaps the most simple, direct, brutal and effective strategy that novice investors can use is to just buy whatever Warren Buffett buys. They don't need to dream about "beating Warren Buffet", they can just “keep up with Warren Buffett" by buying shares in his companies. The easiest way to do this, of course, is to just buy Berkshire Hathaway shares. If novice investors feel that Berkshire Hathaway's share price is too expensive (it was over $310,000 in October of 2019), then they can look at its individual holdings and choose the stocks they want!

CNBC has a page listing all of Berkshire's stock holdings:

Of course, if a novice investor actually did this, their success would be dependent on whether they were able to hold the stocks for as long as Warren Buffett does. For the vast majority of people, holding for the long term is a much bigger challenge than making the initial choice of what to buy.

Alternatively, they could go to Joel Greenblatt's Magic Formula Investing site, enter a few parameters, and buy the suggested collection of stocks. It's important to note, however, that Greenblatt's Magic Formula is not suitable for regular investing, since his method is to choose a new batch of stocks each year. See? Regular investing isn't the only effective strategy, it's just the easiest for most people to put into practice.

So why can we blindly follow these truly successful investors who have shown excellent returns over the long term? It's because they have used their own strategies over the long term, and their strategies have passed the test of time. They are also skilled at thinking with a long-term perspective, or else they wouldn't have been able to carry out their strategies over the long term. In their eyes, the long-term effectiveness of a strategy is not related to how complicated it is. To the contrary, only simple strategies can actually be carried out over the long term. Furthermore, the long-term effectiveness of a strategy is not correlated with the intellect of its user. The core prerequisite for the long-term effectiveness of an investment strategy is whether or not it is faithfully carried out over the long term.

In fact, there is no secret to success. Even if there were, it would be an "open secret". All paths to success are open, as are all of the necessary tools and knowledge. It's just that few people are able to patiently follow a path, picking up knowledge and understanding bit-by-bit, and persistently execute along the way. How few? They're actually quite hard to find.

These people are the rare ones who have achieved a unity of knowledge and action. Actually, the suggestions of anyone in any field throughout history who has achieved a unity of knowledge and action are worth accepting and putting into practice. If we understand it right away, that's great, just do it. If at first we don't understand, we can blindly follow.

The key point is that investing ideas from the most successful investors are free! You don't even need to worry that these ideas will be adopted by everyone and lose their effectiveness, because history has shown that the vast majority of people won't use these ideas. Maybe it's because most people are afraid of simplicity. They think that success is difficult, so they must discover a complicated secret or they won't be able to succeed. There's also another important and common fear involved that keeps people from following this priceless advice: it's terrifying to use our own money to carry out the ideas of others that we still don't understand!

Of course, there's yet another reason:

People like to use their own smarts and efforts to get a reward.

"Even if I make money by buying whatever Warren Buffet buys, it doesn't feel like success." This might be the actual feeling that many people are hiding.

When people talk about value investing and trend investing, they often mistakenly see them as opposites. In fact, they are only opposites when viewed from a short-term perspective.

For regular investors, however, who always view things from a long-term perspective, value investing and trend investing are not opposites. In the long term, which is to say after two full market cycles, value investments will show a trend of compound growth, and investments that trend upward over the long term will also certainly be valuable. A simple change in perspective can cause the relationship between two terms to be completely opposite!

I often say the following:

Don't have blind faith in value investing.

I also often say this:

Don't have a one-sided understanding of value investing.

Why do I feel that I always have to remind people of this? Because I often see this situation:

Most people are clearly (short-term) trend investors, because the bull market was obviously the reason they entered the market! But as soon as they get trapped by falling prices in a bear market, they suddenly become value investors!

So, in most situations, people who mention the concept of value investing to you actually only became value investors after getting trapped in the market. I can also guarantee to you that, once the market picks up, they will suddenly turn into what they would call trend investors.

This is truly a fascinating phenomenon. They completely fail to understand that the huge loss and the awkward situation that they are facing are entirely due to having a different perspective. Even sadder is that these people, who use the short term as the basis for their decisions, also don't know that they have no way of understanding the free and correct advice on the market that is available from those most successful investors who can be blindly followed. And it's all due to a different perspective! Because those "truly successful investors who have shown excellent returns over the long term" all look at things from a long-term perspective.

To take it a step further, trend investing is better than value investing when viewed from a long-term perspective.

Even though Benjamin Graham's value investing thesis is obviously correct, few people notice that it has a hidden limitation:

According to his thesis, you must always pay attention to the current price.

Behind this hidden limitation is an even more deeply hidden factor:

Even though it is possible to determine whether the current price is lower than the current value, it's nearly impossible to determine the future price and value, especially the price and value after two full cycles.

It's an almost impossible feat to both pay attention to the details of the present and seriously consider everything that could happen in the distant future. This is the key reason why truly successful value investors are so rare. A good analogy is the saying that if you wear one watch you'll basically know what time it is, even if it's a few minutes slow or a few minutes fast, but if you wear two watches you'll be very mixed up.

According to value investing theory, you must work hard to find an investment with a price below its actual value. But when will you sell it? According to the theory, once its price exceeds its actual value you should sell it, whether it's been ten days or ten years since you purchased it.

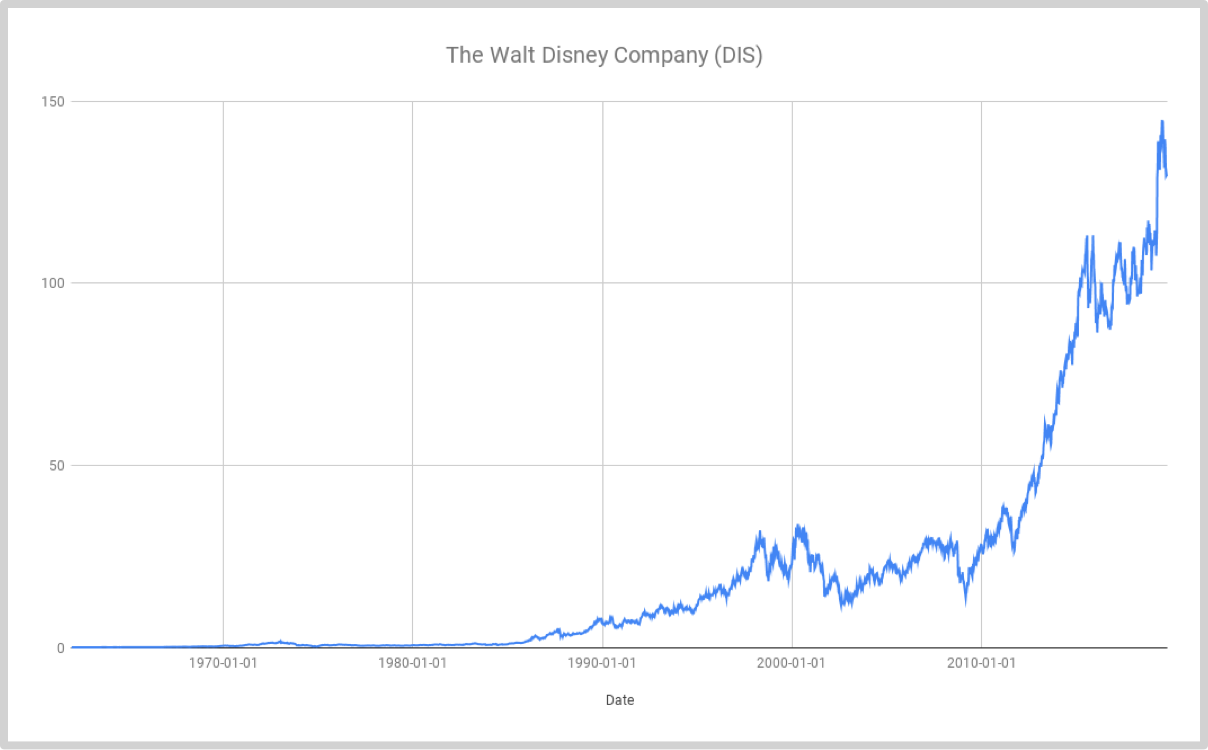

Following this theory, even Warren Buffett will make mistakes. His most famous mistake was his investment in Disney -- he actually made two mistakes trading Disney stock. In 1966, 36-year-old Buffett met Disney founder Walt Disney in California. Following the meeting, Buffett bought 5% of Disney (NYSE:DIS) for $4 million at a price of $0.31 per share.

Note: Historical data is from Yahoo Finance (DIS), and the chart above was created in Google Sheets; you can view the data and chart here.

In his 1995 investor letter, Buffett relayed this story. He bought Disney stock in 1966 at $0.31 per share, and then sold it a year later for $0.48 per share, making a profit of 50%. Over the next thirty years, Buffett could only watch as Disney stock rose, reaching $13 in 1995.

But the story was not over. In 1995, Buffett helped Disney purchase Capital Cities/ABC, of which he was a shareholder, and once again ended up with a 3.6% stake in Disney! He sold his shares within three years, though, and missed out as Disney's stock continued to rise up to $129 in October of 2019. Business Insider calculated that, had Buffett continued to hold 8.3% of Disney through 2019, his shares would have been worth $21 billion, and he would have received $1.5 billion in dividends.

Of course, this story doesn't mean that Buffett failed in his investment, and he certainly didn't actually "lose" $22.5 billion. After all, he made a profit on Disney, and he didn't just spend the money after selling -- he kept investing according to his strategy, and he has a 55-year track record of around 25% returns. Over the past 53 years, not accounting for dividends, Disney has returned just over 19% compounded annually. If dividends are taken in to account, Buffett would have been better off holding Disney, but he certainly didn't "lose" as much trading Disney as some people think.

What this story really tells us is that, over at least two full cycles, value investing, which requires constant focus on price, is not necessarily better than long-term trend investing.

Therefore, regular investors focus more on the overall trend. Even though we are also value investors, the difference is that we view things from a long-term perspective. While it can make people uncomfortable, the logic is sound:

If the correct trend is chosen, then while the difference between price and value is not unimportant, it's not as important as people think.

With a focus on long-term trends, and the requirement of only focusing on the long term, regular investment targets must be chosen in a different way. Compared to many other investors, regular investors have an extra screening criterion:

Sustained growth over the long term.

Don't discount the importance of "one extra criterion".

Amazon (NASDAQ: AMZN) currently has the highest market cap of any e-commerce company in the world. According to Morningstar's calculations, it has provided investors with a compound yearly return of 40.42% over the past five years. Over the past 15 years, the compound yearly return has been 28.51%.

Have you thought about why Amazon started by selling books, even though there were so many other potential items to sell? Aside from the fact that the book market is a large market, and the fact that people need and want to buy books frequently, there is one extra screening criterion that the book market fulfills: once you have sold a book, you very rarely need to provide customer service. Just this one extra criterion eliminated 99.99% of the other choices!

Regular investors can only choose investments that grow sustainably over the long term (of course, the more growth the better!). Just this one seemingly simple criterion eliminates 99.99% of the options, because, strictly speaking, there is no one individual investment that we can be sure will meet this criterion, no matter how good it looks now. This is because companies are just like people:

In the long run, we are all dead. -- John Maynard Keynes

So what should a regular investor do?

Everyone can understand how difficult it is to pick the best possible investment, especially in the midst of price fluctuations. It's as difficult as a world champion archer standing on a boat being rocked by waves in the middle of the ocean hitting the bullseye on a target on the shore.

Only investing in one investment also entails opportunity cost. Time and money are limited resources, and if you use them in one way you can't use them in another. So, if you invested in A but B performs better, the opportunity cost of your investment decision is quantifiable.

Fortunately, we have another simple, direct, brutal and effective solution:

Invest in everything.

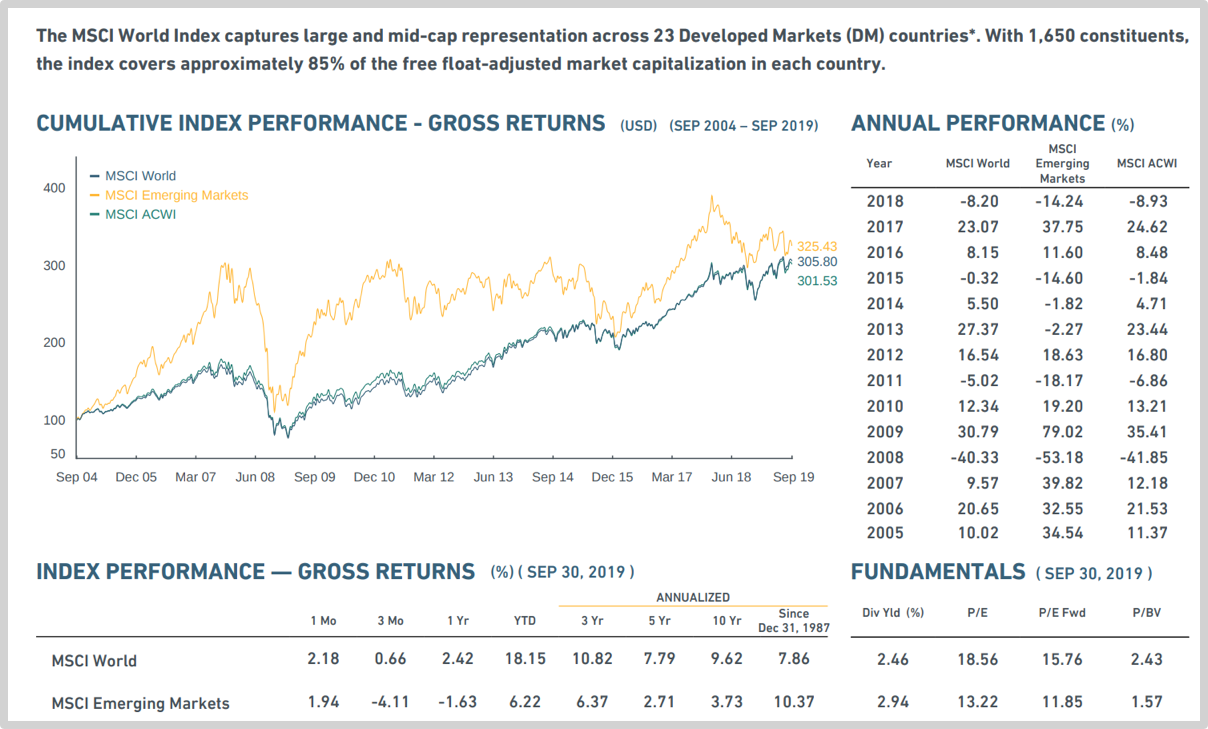

This sounds a little bit crazy, and perhaps a bit stupid, but let's put aside whether it's actually crazy and/or stupid, and first ask: Is it possible to invest in everything? The answer is definitely yes! The MSCI World Index tracks the price of 1,650 mid- and high-cap stocks in 23 developed countries. If we actually invested in this index, what would our results be?

Note: It's possible to buy ETFs that track various world stock indexes. The iShares MSCI World ETF (NYSEARCA: URTH) tracks the MSCI World Index; the iShares MSCI ACWI ETF (NASDAQ: ACWI) tracks the MSCI All Country World Index, which includes emerging markets; and the Vanguard Total World Stock ETF (NYSEARCA: VT) tracks the FTSE Global All Cap World Index, which also includes developed and emerging markets.

In addition to the MSCI World Index, there are several other MSCI indexes, including the MSCI Emerging Markets Index. From December 31st, 1987, to September 30th, 2019, the MSCI World Index has shown yearly compounded returns of 7.86%, and the MSCI Emerging Markets Index has shown yearly compounded returns of 10.37%. This makes sense, as you would expect emerging markets to grow faster, albeit with more risk.

An investment in a fund that tracks the MSCI World Index is like a bet on the growth of the world economy, and an investment in an S&P 500 fund is like a bet on the US economy. If we look again at the chart of the S&P 500, we can see that it has also provided around 9% returns over several decades!

Note: The historical figures above are from Yahoo Finance (^GSPC), and the chart was created in Google Sheets; you can view the chart and data here.

Investing in the S&P 500, with an annual compound growth rate (ACGR) of 9%, performed better than investing in the MSCI World Index, which had an ACGR of 7.86%, but the MSCI Emerging Markets Index performed even better, with an ACGR of 10.37%. What's the easiest way to explain this?

- The US grew faster than the world;

- emerging markets grew faster than the US.

Now we can see that, when we choosing investments, in addition to "one" (quite dangerous) and "all" (mediocre), there is another choice: "part". So which parts are worth choosing? I like this analogy even better than "betting on the world":

Choosing investments is like choosing a method of transportation. If you walk, you can still get there, it will just take longer. But if you have a bike you shouldn't walk, if you have a car you shouldn't bike, and if you have an airplane you shouldn't drive -- you should take whatever will get you there the fastest.

We've seen that emerging markets develop faster, so it's easy, we can just choose the "emerging market part", right? Or could we just choose one fastest-growing country, or even just choose the fastest growing industry in that country? Sure! Choosing a market that is growing faster is just like choosing a faster method of transportation.

It's extremely difficult to pick the best investment out of tens of thousands of possibilities, but it's quite easy to pick a couple of the fastest-growing areas out of ten or so regions. Everyone knows that the US and China are the fastest-growing places in the world. If I were to design an ETF, I would look for my investments in just these two places. This ETF would have a high probability of doing better than the MSCI World Index, wouldn't it? To take it a step further, it wouldn't be that difficult to further limit my investments to the fastest growing one or two industries in each country. At least legendary investor Masayoshi Son doesn't think it would be difficult:

Making money is easy. All you need to have done is invested in the Internet 20 years ago, because at that time the Internet was the future of the world. Now, you should invest in AI, because AI is the future of the world.

I agree with Masayoshi Sun's point of view, and believe that in the foreseeable future AI will be the best industry. However, my point of view is slightly different. For instance, I believe the following:

No matter how good the algorithm is, it needs data to feed it. Public companies with large and growing amounts of user data already have sufficient profit-making ability. If in the future algorithms are large trees, then growing amounts of data are fertile ground. Without fertile ground, the trees can't grow. Most algorithm companies will in the end be used by large companies with data.

When I started to buy lots of bitcoin in 2011, many people thought I was crazy. They all said the same thing: "Isn't it too risky?" They felt like it was too risky, but I had the opposite feeling:

Isn't it too risky not to invest in Bitcoin?

This was the logical reasoning behind this feeling:

We've seen the incredible changes brought about by the Internet allowing information to flow rapidly with basically zero cost, so what kind of incredible changes would be brought about if assets could also flow rapidly with basically zero cost?

After ten years, the Internet is still bringing about massive changes. Even if it isn't exactly what we initially imagined, it's still amazing. In the same way, ten years from now the financial Internet is extremely likely to have brought about incredible changes, even if we can't know exactly what those changes will be...

So for me at the time, blockchain was the future, blockchain was a trend, and blockchain would likely be the fastest growing industry. Looking back from eight years later, it has become the fastest growing industry, and my investment has grown at a scale not even imaginable at the time.

You see? "Choosing the fastest growing sector" is the most simple, direct, brutal and effective method. It's also the most direct conclusion that can be derived from macro observation. For those who can't think based on the long term, this statement isn't understandable as an effective piece of advice. To them, it seems stupid, and you can imagine them yelling out, "Who doesn't know this!?" Yes, everyone knows this, but not everyone thinks based on the long term, so they are not used to macro observation, and so of course they can't understand the power of long-term macro observation.

Can we take it further, and ask ourselves, "Can I choose the fastest growing company in this fastest growing sector?" I don't think it's worth it, because doing so is essentially returning to the most dangerous situation, and becoming more vulnerable to regression to the mean. The core skill of macro observation is very simple: don't go to extremes. The reason is that we hate risk, and we hate systematic risk even more. The core strategy is always "a part of a part":

- Look for one or more regions in the world;

- in those regions look for one or more sectors;

- in those sectors look for the best companies...

However, whether we're choosing regions, sectors, companies or projects, we should never pick just one. So in a global sector such as blockchain, as long as opportunities are available, my choice is no longer a single investment, but the mix of investments in BOX, which includes BTC, EOS, and XIN.

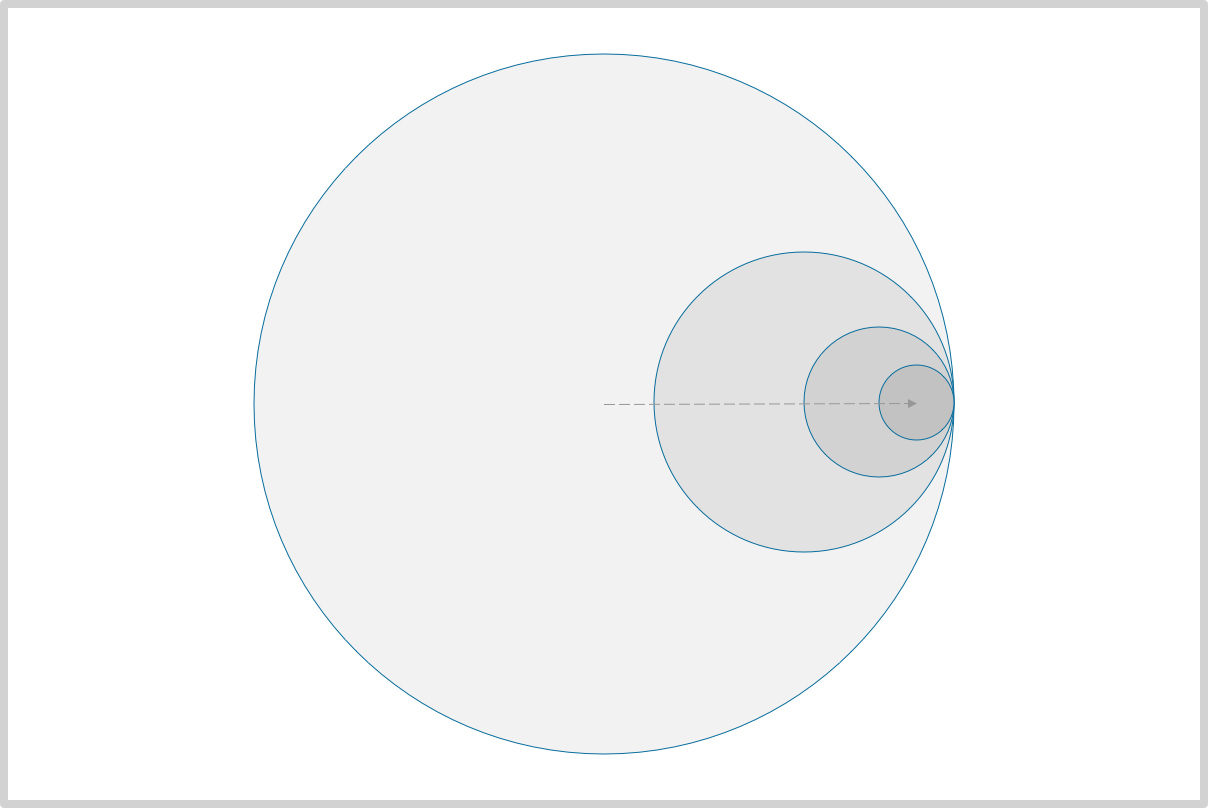

The diagram below may make it easier to understand.

The largest circle represents the entire world, and you are standing in the middle holding a bow and arrow....

You look around, hoping to find the best place to shoot your arrow. It's difficult, because in the entire circle there are limitless places to chose, and it's basically impossible for you to choose the best possible place and hit it from so far away...

So you think about it, and you choose "everywhere". You decide to change tools, and trade your arrow for a net. This is much better! It's easy, and even if the results are average, it's much better than shooting arrows all day and hitting nothing...

But you'd like to have better results, so you first choose a general direction. You're not just choosing randomly, you have a reasonable basis for your choice: you decide to shoot your arrow in the direction of the area that is developing most rapidly. This way you're more likely to hit something, right? Or you could put down your arrows, and just throw your net in that direction!

But then you realize that you could use the same basic rationale to adjust your general direction. If there are regions that are growing more rapidly, then there must also be sectors within those regions that are growing the most rapidly. The same logic still works.

You've already made three guesses: 1) a net might work better than an arrow; 2) certain regions might grow more rapidly than the whole; and 3) some sectors within those regions might grow even more rapidly. If you keep guessing, your accuracy will certainly suffer. So what should you do? Don't use an arrow, use a shotgun! This way, although your accuracy will suffer, you'll be more likely, and perhaps almost certain, to hit something. Anyway, since it's so far away, no one can be completely accurate, but after so many adjustments, you're more likely than others to be accurate!

In the end, you have another discovery, which is that using an arrow is never the best choice...

Choosing a mix of multiple investments, rather than just one, has a powerful effect. The most famous example once again comes from Warren Buffet. In April of 2017, United Airlines had a PR disaster on their hands when, after overselling a flight, they had 69-year-old David Dao dragged off of an aircraft. Quite a few of the media reports that followed were about Warren Buffett, because he owned a large amount of stock in United's parent company. The reports said that, since the company's stock had gone down 4%, losing more than $1 billion in market value, Buffett had lost more than $90 million. At the end of trading that day, the stock was down just over 1%, so Buffett's paper loss was around $24 million.

But did Buffett really lose money? No. In addition to United, he also had stock in American Airlines, Delta Airlines, and Southwest Airlines. The stock prices of those three airlines all went up that day, giving Buffett an overall paper gain of $140 million on his airline stocks! Buffett's diversification in the airline sector insulated him from the price volatility of a single airline stock. Had Buffett not had diversified his holdings in the airline sector, the result would have been quite different!

Words that have been paired most frequently with "bubble" include "tulip" and "Internet". In 2019, a new one has been added: "Artificial Intelligence". People are worried that that a global AI bubble is about to burst, even though just a year ago startups in the AI sector were the hottest in the world. On October 5th, 2018, Forbes reported that there were 14 AI unicorns just in China (a "unicorn" is a startup with a valuation of over $1 billion). In aggregate, these companies had valuations of over $40 billion. A year previously, AI startups had been even hotter, with a report from Tsinghua University stating that 369 investments had been made in AI startups in China, with the total investment reaching $27.7 billion.

But why are people suddenly worried about a bubble? It's because there has been a rash of negative news stories about the AI sector. For instance, it was reported that Facebook infringed on user privacy in order to develop their voice recognition system, and that IBM used similar methods to develop their facial recognition system. AI has also been used for what some consider to be nefarious purposes, such as in the case of Cambridge Analytica's use of Facebook user data in the US elections, and Amazon's use of AI to fire low-productivity workers.

Perhaps the silliest story was about Kiwi Campus, a startup founded at UC-Berkeley in 2017 that makes robots, called Kiwibots, that deliver food on campuses. It has received multiple rounds of funding, and its CEO received an entrepreneurship award from MIT in 2018. In the summer of 2018, however, it was reported that the "AI robots" were actually being controlled remotely by students in Columbia being paid $2 an hour.

The AI sector seems too hot. With startups raising too much money, unclear valuation methods, and frequent issues with applications of the technology, it's hard not to be reminded of the Internet bubble. So, of course, people start to worry that there may be an AI bubble that could burst...

But is it such a bad thing for a bubble to burst?

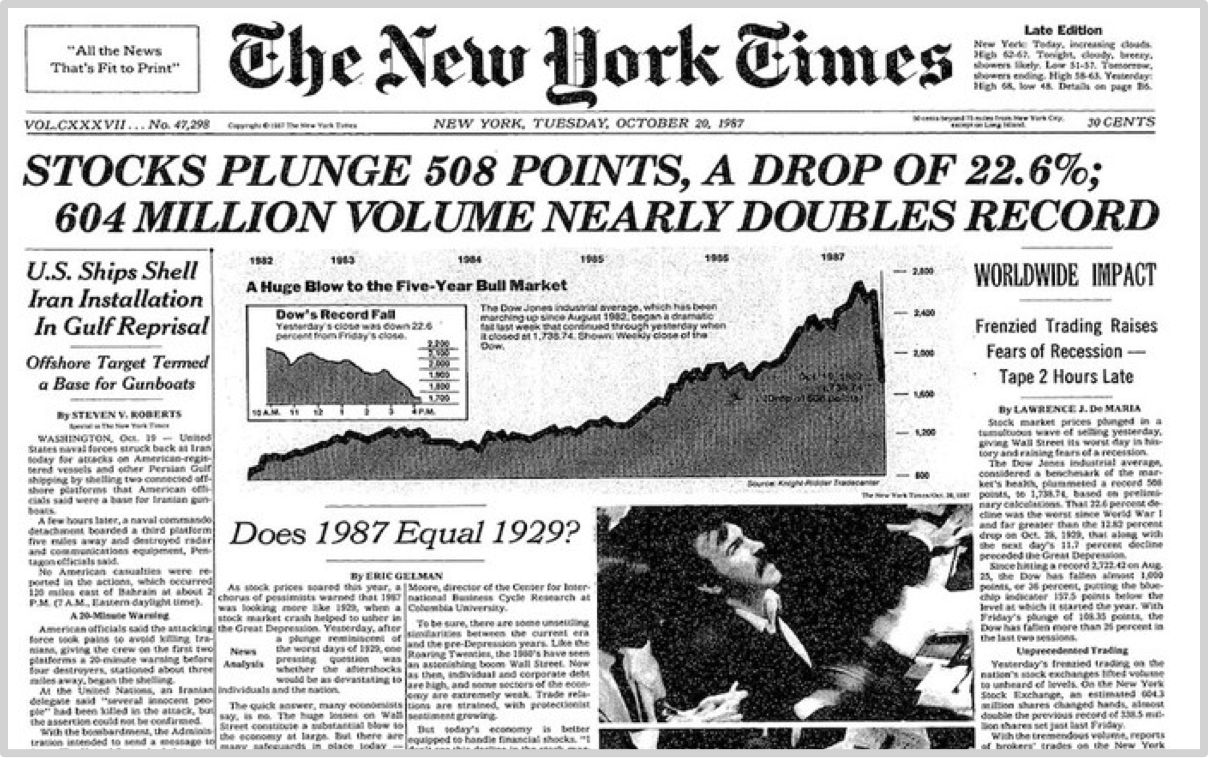

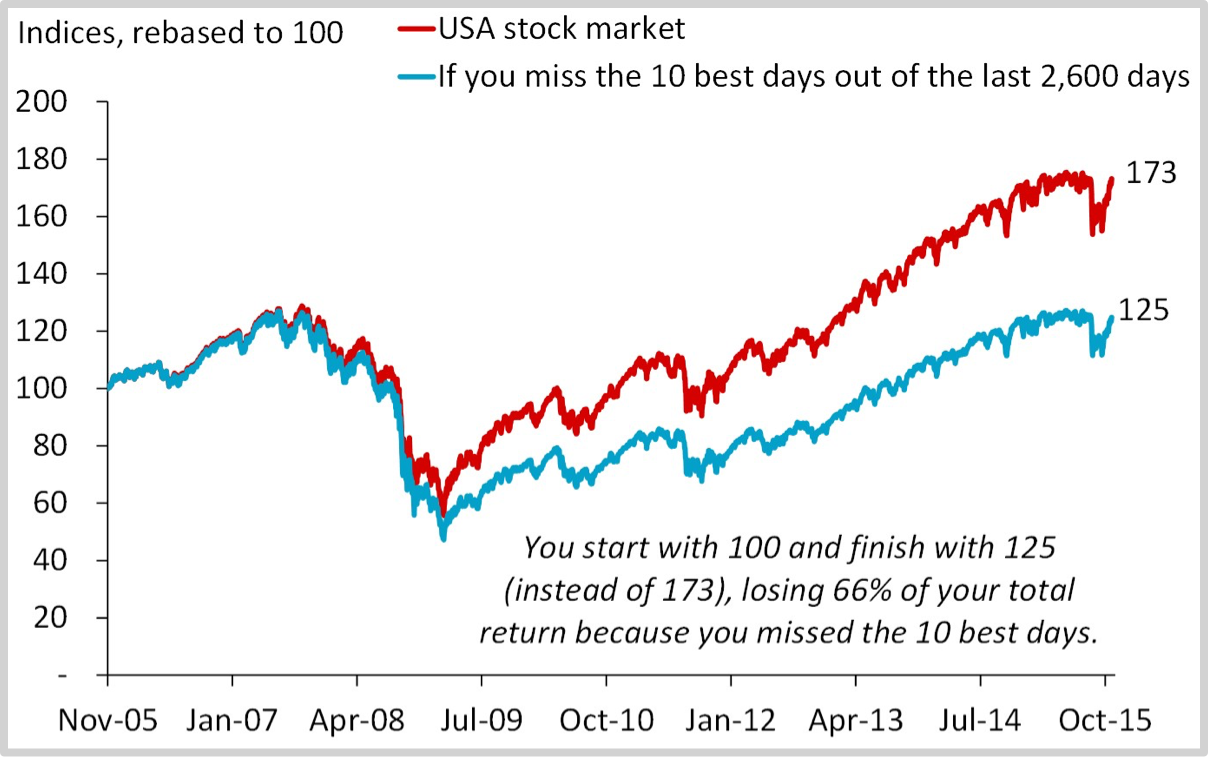

Let's take another look at the historical price chart for the S&P 500. The two red circles indicate the peak of the Internet bubble in 2000 and the peak of the housing bubble that led to the financial crisis in 2008. If we were living in the world of 2000 to 2003, it would seem to be a terrible winter for the Internet, with companies going bankrupt and dissolving. From our vantage point in 2019, however, we can see that from 2000 to 2019 the Internet grew from being the world of a few to being everyone's world. According to the World Bank, in 2000 only 1.8% of people in China were online; by 2019, WeChat -- just one app -- had over 1.1 billion users. This is the story of the Internet in China -- from 1.8% of the population using the Internet to 70% of people using just one app in around 20 years. Long-term trends can take a while, but they are quite powerful!

For regular investors, even if we entered the market at the height of the bubble in 2000, looking back after two full cycles, in 2015, our entry point still looks like a "low" price. It turns out that the secret to "buy low, sell high" is quite simple:

Wait for a long time after you buy before you sell.

So is the popping of the AI bubble a good thing or a bad thing? It's hard to say for others, but for regular investors a bubble popping is always a good thing. In fact, the popping of a bubble may be a great opportunity for a regular investor to enter the market.

If we look back over history, industries representing all great trends went through bubbles. The difference between the tulip bubble and the Internet bubble was that, while tulips were not completely without value, there was no way for their value to grow sustainably. The Internet, however, had a value that could grow over time. All the way through the Internet bubble the Internet was growing, creating value, and changing the world.

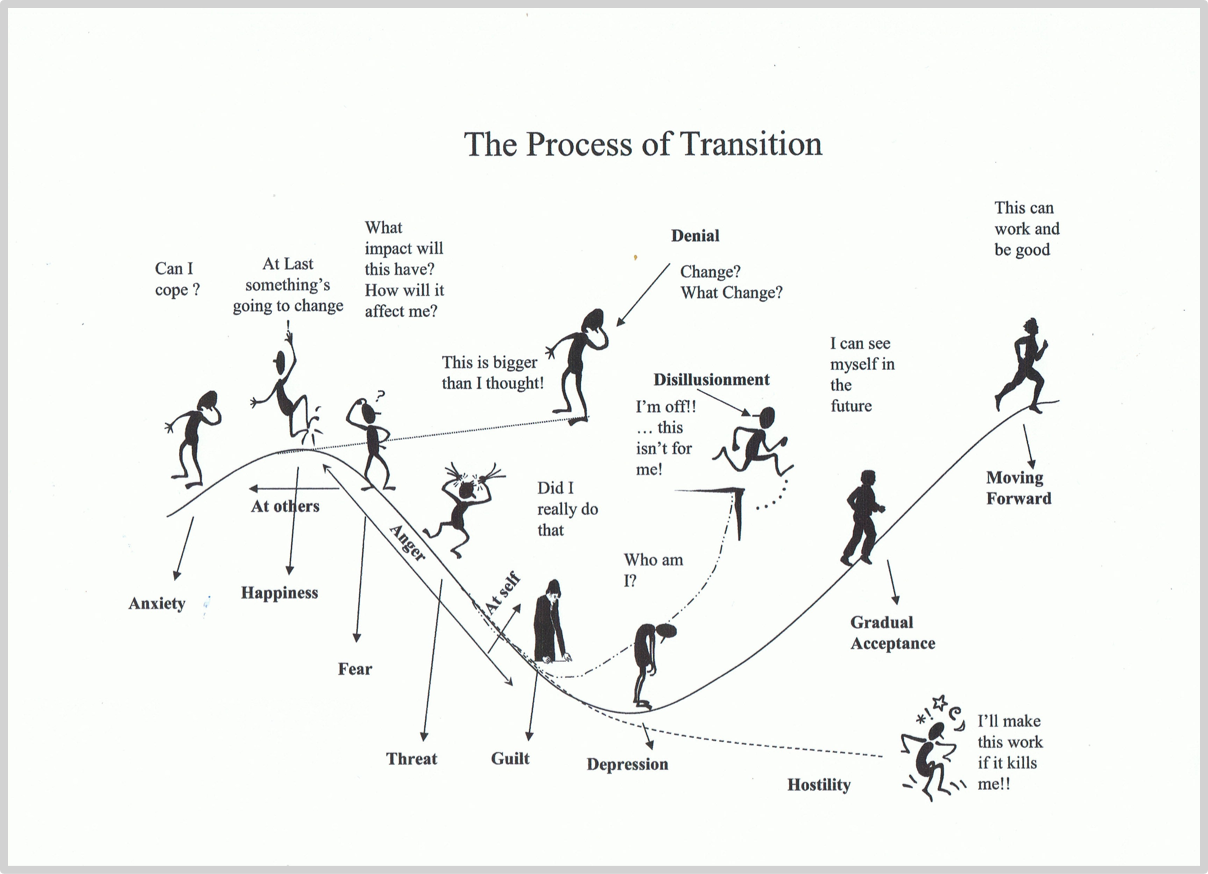

Why do all great trends go through bubbles? The best explanation comes from John Fisher's Transition Curve:

When going through a transition, after some initial anxiety, people feel happy because they think that, "At last something's going to change!" But then they often begin to experience a myriad of negative emotions. Some people deny the negative emotions, and then crash later on, while some slowly fall into feelings of fear, guilt and even depression. While some eventually give up, others slowly begin to accept and adapt to the change. But this only happens after a long process.

Major trends, which become apparent after many years, must initially go through the process of acceptance described above. The first crest in the curve is the cause of the bubble, and the ensuing trough is the reason for the bubble bursting. This is shown most clearly in the markets, because the market price at each moment is a representation of everyone in the market's collective understanding of an investment. When people are feeling disillusioned, the bubble pops.

So, contrary to what most people think, the popping of a bubble quite possibly represents opportunity. Whether or not there actually is an opportunity depends on whether or not the object of the bubble has long-term sustainable value and growth potential. If it does, then there is an opportunity. It's possible, though, that bubbles may continue to occur until its value has been fully realized.

After reaching an all-time high of $19,800 in December of 2017, bitcoin entered a long bear market. As of October 2019, it remains in a bear market, with its price less than 43% of its all-time high. But is the popping of this bubble different from the popping of previous bubbles in the bitcoin market? From its inception through October 11th, 2019, bitcoin, the world's first blockchain application, was pronounced dead 337 times. Each short bull market has been called a bubble, and they have all popped, but the popping of the bubble in 2017 has one difference from previous bubbles:

No one denies bitcoin's value.

This is an extremely important, if subtle, difference. I have a very simple, direct, brutal and effective way to determine if a trend has been established:

Don't look at how many people have already accepted it, look to see if most people can no longer deny it.

Undeniability is an important sign of an established trend. It doesn't matter whether or not they understand it, or whether or not they accept it. If they can't deny it, then the trend has basically already "filled up the bubble". This is the best signal for regular investors to decide when to enter the market. This is why I didn't introduce BOX, my no-carry, no-management-fee blockchain ETF, until July of 2019, even though my thinking about and designs for a blockchain ETF began in 2015.

It's important to point out that most novice investors fall into the trap of "looking for the next...". Actually, very few people succeed by choosing carefully and holding over the long term (whether through regular investing or not), and the vast majority of people never make deep macro observations from a long-term perspective, but everyone is jealous of those who have already succeeded, so they can't help but think:

If only I had also chosen correctly that early!

But it's hard for that thought not to evolve into this next thought:

I also want to find an investment that I can get in early on!