Let's learn git!

Following the main README.md you should go through the installation process for your machine as well as the required git config commands.

Note: You'll see $ these a lot. Don't actually type them in! They just mean you're entering a command!

Git needs to know two things about you to associate you with your commits. Name and email address - don't worry, you will never be emailed. Also, this is not making an account, just setting variables in a configuration file.

Do so like the:

$ git config --global user.name "Darth Vader"

$ git config --global user.email "[email protected]"

The --global flag tells git that you want your name and email address to be the same across all of the repositories you work in, not just the current one.

A repo is simply a directory (folder) being tracked by git. Tracking means that git keeps track of the changes made to files inside the folder.

So to make a repo, we first need a directory. Let's make one:

$ mkdir deathstar

$ cd deathstar/

Now we should be inside our deathstar directory. Let's check by using the print working directory command, pwd.

$ pwd

/home/vader/deathstar

Cool, but this is just a directory (or folder) without git! Let's initialize git in our directory:

$ git init

Initialized empty Git repository in /home/vader/deathstar/.git/

Sweet! The entire deathstar directory is now being tracked by git. Git uses the hidden folder ./git/ to keep track of changes – don't delete it!

We can verify that git is tracking deathstar by using the git status command:

$ git status

On branch master

Initial commit

nothing to commit (create/copy files and use "git add" to track)

As Lord Vader, we want to tell our troops what to do. Make a text file to keep all your orders in:

$ touch orders.txt

$ ls

orders.txt

Now open your text editor of choice and add the following line to orders.txt

$ vim orders.txt

$ cat orders.txt

Tear this ship apart until you find those plans

Now that we have orders.txt with content we should use our best friend git status to see what git thinks of the state of our repo right now.

$ git status

On branch master

Initial commit

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

orders.txt

nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)

Notice how git says orders.txt is untracked? That means git recognizes that this is a new text file. To tell git to start tracking changes to orders.txt, we need to add it to the staging area:

$ git add orders.txt

Right. Now git is keeping track of changes to that file. Now lets see what our status is after adding it:

$ git status

On branch master

Initial commit

Changes to be committed:

(use "git rm --cached <file>..." to unstage)

new file: orders.txt

As you can see, we've added the new file orders.txt to git's tracking. Whenever you modify, create, or delete a file, git will tell you to add those changes.

Now that we've made a new file, added content to it and added it to staging, time to package them into commit with a description.

$ git commit -m "Add initial orders"

[master (root-commit) 6323231] Initial Commit

1 file changed, 1 insertions(+)

create mode 100644 orders.txt

We've just made a commit with everything we've done until this point and given it a description "Add initial orders", which people will see when they look through the history of changes.

Next time you made changes to a file(s), go through the adding process and then this committing process. Rinse, repeat.

For this example, lets make another commit.

Open orders.txt and add the following line to the end:

Bring me YOUR_NAME - I want them alive

Then go through the adding the changes (above), and the commit them like we just did.

This time write a different commit message. It should describe what changes you've made.

So we've made a few commits. Now let's browse them to see what we changed.

Fortunately for us, there's git log. Think of Git's log as a journal that remembers all the changes we've committed so far, in the order we committed them. Try running it now:

$ git log

commit 3ef1ee7e39dc69a5e14119a0cca6d951b5e86c95

Author: Darth Vader <[email protected]>

Date: In a galaxy far, far away

Get the passengers

commit 6323231533dcee3e9f80cc20f99dc991d4e2e34f

Author: Darth Vader <[email protected]>

Date: A long time ago

Add initial order

Up until now, the work we've been doing has been on our local computer, nothing has left our little folder... time to change that.

We're going to assume you have a Github account. Sign in now or make one.

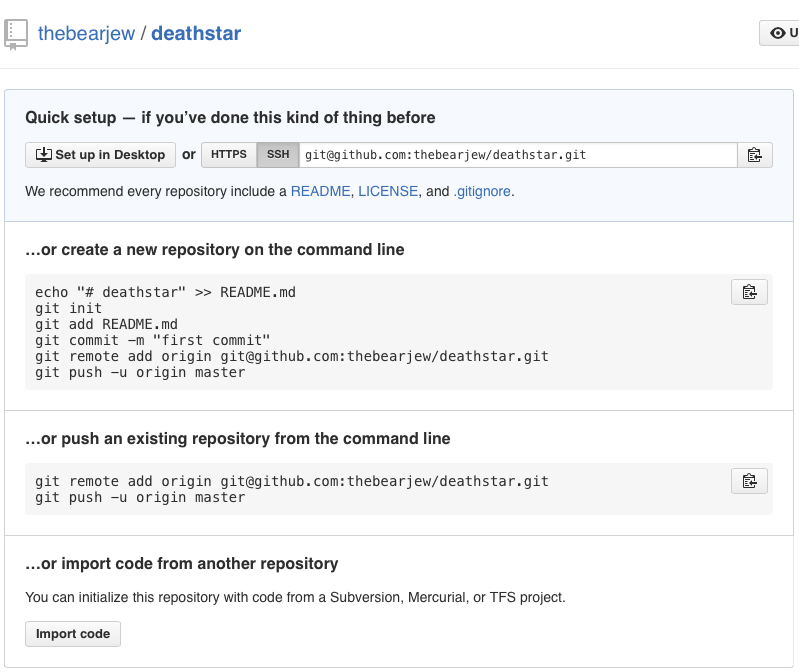

Now, on Github make a new repo with the same name as our directory - "deathstar"

Thankfully, Github has been nice and explained how we can link our folder and this one (remote) together.

First we'll add the URL of this repository to our local folder, and name it origin with this command:

$ git remote add origin https://github.com/YOUR_USERNAME/deathsar.git

Pushing is simply update your remote repository with the commits you've made on a branch.

We're on the master branch with two commits (the ones we just made). And we want to send this to our repository on Github. Lets push the commits to the corresponding branch:

$ git push -u origin master

Counting objects: 3, done.

Delta compression using up to 4 threads.

Compressing objects: 100% (2/2), done.

Writing objects: 100% (3/3), 804 bytes | 0 bytes/s, done.

Total 3 (delta 0), reused 0 (delta 0)

To [email protected]:YOUR_USERNAME/deathstar.git

* [new branch] master -> master

Branch master set up to track remote branch master from origin.

This means push to the origin (https://github.com/YOUR_USERNAME/deathstar.git) branch called master (the same one we're on). If we were on another branch, we would push to the branch with the same name.

Git is also telling us that the remote now has a new branch called master! The same one we were working on

Note: The -u is only used the first time to connect branches between local and remote repositories. Next time you push do so like this $ git push origin branch-name.

Refresh the page on your Github repo!

In order to practice pulling, you need to work with another person. So turn to the person next to you, say hi, ask their name, and their Github username.

One person will be called "Developer A" and the other "Developer B".

Dev A should add Dev B as a collaborator on their Github repository (https://github.com/DEVELOPER-A/deathstar.git).

You can do that by going to Settings > Collaborators > Then add Dev B's username.

Dev B should now clone Dev A's repository on Github.

$ cd

$ git clone https://github.com/DEVELOPER-A/deathstar.git deathstar-other

Cloning into 'deathstar-other'...

remote: Counting objects: 3, done.

remote: Compressing objects: 100% (2/2), done.

remote: Total 3 (delta 0), reused 3 (delta 0), pack-reused 0

Receiving objects: 100% (3/3), done.

Checking connectivity... done.

Congrats Dev B, you just clone Dev A's work! Now cd into the repo and open up orders.txt... You should see Dev A's print statement at the end:

Bring me DEVELOPER-A - I want them alive

Okay Dev B, your time to shine!

Edit orders.txt and give (type up) any order you like.

- Add the changes

- Commit the changes

- Push the commits to the master branch on Dev A's repo

If you need help, there are mentors around the room ready to help you

Your turn Dev A. So your friend and made a commit to your repo, awesome!

But how do you get those changes onto your local repository? With pulling. Pulling is simply the opposite of pushing (duh!) - it means there are things on the remote you don't have which you want, so you pull them down to your computer.

Here's a picture to visualize

Time to pull:

$ git pull

remote: Counting objects: 4, done.

remote: Compressing objects: 100% (1/1), done.

remote: Total 4 (delta 2), reused 4 (delta 2), pack-reused 0

Unpacking objects: 100% (4/4), done.

From github.com:thebearjew/deathstar

c6ff65f..9b39773 master -> origin/master

Updating c6ff65f..9b39773

Fast-forward

orders.txt | 2 ++

1 file changed, 2 insertions(+)

Now, Dev A, open your orders.txt file and you should see the additions that Dev B made!

Pulling worked!

Branching is actually the most important feature of Git. It allows 2 or 2,000 developers work on the same code without writing over or deleting each other's work.

So we just learned the ins-and-outs of pulling and pushing our changes (or commits) to a repository.

However, what happens if Dev A decides to rename orders.txt to chill.txt?

Dev B will still have their file named orders.txt. After they edit orders.txt, add the changes, commit them, and push them, they might get this error.

$ git push origin master

To [email protected]:DEVELOPER-A/deathstar.git

! [rejected] master -> master (fetch first)

error: failed to push some refs to '[email protected]:DEVELOPER-A/deathstar.git'

hint: Updates were rejected because the remote contains work that you do

hint: not have locally. This is usually caused by another repository pushing

hint: to the same ref. You may want to first integrate the remote changes

hint: (e.g., 'git pull ...') before pushing again.

hint: See the 'Note about fast-forwards' in 'git push --help' for details.

Dev B is unable to push because Dev A made changes and pushed them before Dev B did.

Now Dev B should try to $ git pull and see what happens -> a merge conflict.

A merge conflict is the same as two people trying to write on the same line of paper at the same time. We can avoid this by giving each person a copy of the paper and let them work on their own, this is branching.

Both Dev A and Dev B should make their own branches:

#Dev A

$ git checkout -b feature/<DEVELOPER_A_NAME> <-"jake" for example

Switched to a new branch 'feature/<DEVELOPER_A_NAME>'

#Dev B

$ git checkout -b feature/<DEVELOPER_B_NAME>

Switched to a new branch 'feature/<DEVELOPER_B_NAME>'

The command $ git checkout -b branch-name creates a branch and simultaneously switch to it.

checkout allows you to jump between branches. Do so later by using $ git checkout branch-name

We can see that we made the branch successfully by asking Git to list the branches

$ git branch -a

*feature/<YOUR_NAME>

master

remote/origin/master

Dev A Add the following to orders.txt

Come to the dark side

Dev B add the following to orders.txt

Overthrow the emperor

Both Devs add, commit, and push like so $ git push origin feature/<YOUR_NAME>

Now check the Github repo and you should see 3 branches at the top.