For my 6th F# Advent submission (6 years in a row!!), I worked on combining the lessons I learnt from my last 2 submissions: 2020: Bayesian Inference in FSharp and 2021: Perf Avore: A Performance Analysis and Monitoring Tool in FSharp by developing a Bayesian Optimization algorithm in F# to solve global optimization problems for a single variable that can be used in the context of performance tuning and optimization amongst other use cases.

Bayesian Optimization is an iterative optimization algorithm used to find the most optimal element like any other optimization algorithm however, where it shines in comparison to others is when the criterion or objective function is a black box function. A black box function indicates the prospect of a lack of an analytic expression or known mathematical formula for the objective function and/or details about other properties for example, knowing if the derivative exists for the function so as to make use of other optimization techniques such as Stochastic Gradient Descent.

In this submission, I plan to demonstrate how I developed and applied the Bayesian Optimization algorithm to various experiments including one making use of Event Tracing for Windows (ETW) profiles to obtain the best parameters and highlight how I made use of F#'s functional features. In terms of using F#, I have had a fabulous experience, as always! I have expounded on this here.

The motivation behind this submission is 2-fold:

- I have been very eagerly trying to learn about Bayesian Optimization and figured this was a perfect time to dedicate myself to fully understanding the internals by implementing the algorithm in FSharp.

- I am yet to find a library (if you know of one, please let me know) that naturally combines Bayesian Optimization with Performance Engineering in .NET to come up with optimal parameters to use for a specified workload. I believe the applications of this are many in the field of performance engineering and figured I create reusable components that can be leveraged by others.

To kick things off and to be concrete about the objectives of this submission, the 3 main goals are:

- To Describe Bayesian Optimization.

- To Present Multiple Applications of the Bayesian Optimization Implementation from Simple to More Complex in the Form of Repeatable Experiments:

- Maximizing

Sinfunction between -π and π. - Minimizing The Wall Clock Time of A Simple Command Line App: Finding the minima of the wall clock time of execution of an independent process based on the input.

- Minimizing The Percent of Time Spent during Garbage Collection For a High Memory Load Case With Bursty Allocations By Varying The Number of Heaps: Finding the minima of the percent of time spent during garbage collection based on pivoting on the number of Garbage Collection Heaps or Threads using Traces obtained via Event Tracing For Windows (ETW).

- Maximizing

- Describe the Implementation of the Bayesian Optimization Algorithm and Infrastructure

If some or all parts of the aforementioned aspects of the introduction and goals so far seem cryptic, fret not as I plan to cover these topics in detail. The intended audience of this submission is any developer, data scientist or performance engineer interested in how the Bayesian Optimization algorithm is implemented in a functional-first way.

The goal of any mathematical optimization function is the selection of the "best" element vis-à-vis some criterion known as the objective function from a number of available alternatives; the best element also known as the optima here can be either the one that minimizes or maximizes the criterion.

Mathematically, this can expressed as:

i.e., finding the value of

The way I understood this algorithm was through a socratic approach and here are the questions I had when I first started diving into this topic that I gradually answered:

Bayesian Optimization is an iterative optimization algorithm used to find the most optimal element like any other optimization algorithm however, where it shines in comparison to others is when the criterion or objective function is a black box function. A black box function indicates the prospect of a lack of an analytic expression or known mathematical formula for the objective function and/or details about other properties for example, knowing if the derivative exists for the function so as to make use of other optimization techniques such as Stochastic Gradient Descent.

To contrast with 2 other popular optimization techniques namely, Grid Search Optimization and Random Search Optimization whose intractability and efficiency, respectively come into question, Bayesian Optimization uses information from previous iterations to get to the optima in a more computational efficient and directed way based on the data.

To summarize, Bayesian Optimization aims to, with the fewest number of iterations, find the global optima of a function that could be a black box based function by making use of previous data points to make the best guess as to where the global optima could be.

There are 3 main components:

- The Surrogate Model: The surrogate model is used as for approximation of the objective function where new points can be fit and predictions can be made. More details are here.

- The Acquisition Function: The acquisition function helps discerning the next point to sample. More details are here.

- The Iteration Loop: The loop that facilitates the following:

- Make predictions using the surrogate model.

- Based on the predictions from 1., apply the acquisition function.

- Identify the point that maximizes the acquisition function.

- Update the model with the new data point.

Diagrammatically,

The efficiency of the Bayesian Optimization algorithm stems from the use of Bayes Theorem to direct the search of the global optima by updating prior beliefs about the state of the objective function in light of new observations made by sampling or choosing the next point to evaluate as a potential candidate for the global optima. For those new to the world of Bayes Theorem, I have written up a summary that can be found here as a part of a previous advent submission.

To elaborate a bit more, (there is a section below under Gaussian Processes that covers the model most commonly used for this purpose of approximating the objective function) we choose a surrogate model that helps us with approximating the objective function that's initialized based on some prior information and is updated as and when we sample or observe new data points. Subsequently with each iteration, we construct a posterior distribution that is incorporative of the previously observed data points with the expectation that over time it more closely represents the actual objective function which, as mentioned before, can be a black-box function.

- Results Are Extremely Sensitive To Model Parameters: Having some prior knowledge of the shape of the objective function is helpful as otherwise, choosing the wrong parameters results in a need for a higher number of iterations or sometimes convergence to the optima isn't even possible. The previous implication requires "optimization of the optimizer". Additionally, this effect is amplified with a inputs of higher dimensions i.e. you have to carefully choose the model parameters for a lot of variables. As we will see later, we need to make some reasonable choices in terms of:

- The Kernel Parameters.

- Resolution of the Initial Data or how granular our model should be in terms of data points.

- Number of iterations.

- Model Estimation Takes Time: Getting the surrogate model to a point where it is behaving like a reasonable approximation of the true objective function can take quite a few iterations dependent on the shape of the objective function, which implies more time spent to get the result.

- Naive Implementation Isn't Parallelizable By Default: We need to add more complexity to the model to be able to parallelize the algorithm.

Here are some FAQs in terms of the usage of the library:

-

Kernel Parameters For the Squared Exponential Kernel: Length Scale and Variance: The length controls the smoothness between the points while the Variance controls the vertical amplitude. A more comprehensive explanation can be found here but in a nutshell, the length scale determines the length of the 'wiggles' in your function and the variance determines how far out the function can fluctuate.

-

Resolution: Our priors are uniformly initialized as a list ranging from the min and max provided when we create the model. The resolution indicates the number of elements we'd want in the priors that'll be initialized as a uniform list. The code for this is as follows:

// src/Optimization.Core/Model.fs

let inputs : double list = seq { for i in 0 .. (resolution - 1) do i }

|> Seq.map(fun idx -> min + double idx * (max - min) / (double resolution - 1.))

|> Seq.toListThe idea here is to use a higher resolution where precision is of paramount importance i.e. you can guess that the optima will require many digits after the decimal point.

-

Iterations: The number of iterations the Bayesian Optimization Algorithm should run for i.e. the number of times the objective function will be computed by running the workload to get to the optima. The more the better, however, we'd be wasting cycles if we have already reached the maxima and are continuing to iterate; this can be curtailed by early stopping.

-

Range: The Min and Max whose inclusive interval we want to optimize on.

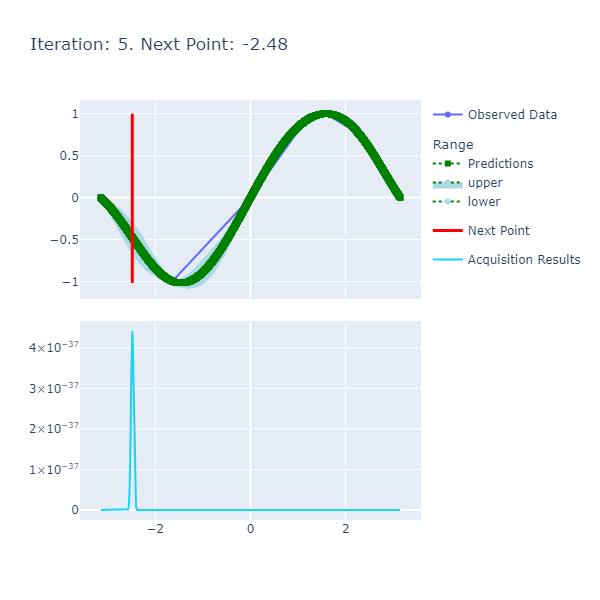

An example of a chart the algorithm is:

Here are the details:

- Predictions: The predictions represent the mean of the results obtained from the underlying model that's the approximate of the unknown objective function. This model is also known as the Surrogate Model and more details about this can be found here. The blue ranges indicate the area between the upper and lower limits based on the confidence generated by the posterior.

- Acquisition Results series represents the acquisition function whose maxima indicates where it is best to search. More details on how the next point to search is discerned can be found here.

- Next Point: The next point is derived from the maximization of the acquisition function and points to where we should sample next.

- Observed Data: The observed data is the data collected from iteratively maximizing the acquisition function. As the number of observed data points increases with increased iterations, the expectation is that the predictions and observed data points converge if the model parameters are set correctly.

Now that a basic definition, reason and other preliminary questions and answers for using Bayesian Optimization are presented, I want to provide some pertinent examples that'll help with contextualizing the associated ideas and highlight the usage of the library.

In this section, I plan to go over 3 main experiments conducted using the optimization algorithm to demonstrate the efficacy of the algorithm and ease of use of the library.

Sin(x) is a Trigonometric Function whose maximum value is 1 if the input is

The experiment can be setup in the following way making use of the library I developed that implements the Bayesian Optimization algorithm:

open Optimization.Domain

open Optimization.Model

open Optimization.Charting

let iterations : int = 10

let resolution : int = 20_000

// Creating the Model.

let gaussianModelForSin() : GaussianModel =

let squaredExponentialKernelParameters : SquaredExponentialKernelParameters = { LengthScale = 1.; Variance = 1. }

let gaussianProcess : GaussianProcess = createProcessWithSquaredExponentialKernel squaredExponentialKernelParameters

let sinObjectiveFunction : ObjectiveFunction = QueryContinuousFunction Trig.Sin

createModel gaussianProcess sinObjectiveFunction ExpectedImprovement -Math.PI Math.PI resolution

// Using the Model to generate the optimaResults.

let model : GaussianModel = gaussianModelForSin()

let optimaResults : OptimaResults = findOptima { Model = model; Goal = Goal.Max; Iterations = iterations }

printfn "Optima: Sin(x) is maximized when x = %A at %A" optimaResults.Optima.X optimaResults.Optima.YThe result of the experiment is: Optima: Sin(x) is maximized when x = 1.570717783 at 0.9999999969.

The optima (maxima, in this case) is very close to the real maxima of

To help better visualize what's happening under the hood, I have created some charting helpers that chart the pertinent series for each iteration and wrap them up into a gif. These charts can be found here.

[<Literal>]

let BASE_SAVE_PATH = @".\\resources\\"

let allCharts : GenericChart.GenericChart seq = chartAllResults optimaResults

saveCharts BASE_SAVE_PATH allCharts |> ignore

let gifPath : string = Path.Combine(BASE_SAVE_PATH, "Combined.gif")

saveGif BASE_SAVE_PATH gifPath |> ignoreThe output gif that's the combination of the iterations is:

The function is smooth and therefore, the length scale and variance of 1. respectively are sufficient to get us to a good point where we achieve the optima in a few number of iterations. The caveat here, however, was the selection of the resolution that had to be high since we want a certain degree of precision in terms of calculating the optima.

This experiment is an example of a mathematical function being optimized. More examples of these can be found here in the Unit Tests.

The Objective Function meant to be minimized here is the wall clock time from running a C# program, our workload, that sleeps for a hard-coded amount of time based on a given input. The full code is available here.

The gist of the trivial algorithm is the following where we sleep for the shortest amount of time if the input is between 1 and 1.5, a slightly shorter amount of time if the input is >= 1.5 but < 2.0 and the most amount of time in all other cases. The premise here is to try and see if we are able to get the optimization algorithm detect the inputs that trigger the lowest amount of sleep time and thereby, the minima of the wall clock time of the program in a somewhat deterministic fashion.

The logic looks like:

// src/Workloads/SimpleWorkload/Program.cs

private const int DEFAULT_SLEEP_MSEC = 2000;

private const int FAST_SLEEP_MSEC = 1000;

private const int FASTEST_SLEEP_MSEC = 50;

switch (o.Input)

{

case double n when n >= 1.0 && n < 1.5:

{

Thread.Sleep(FASTEST_SLEEP_MSEC);

break;

}

case double n when n >= 1.5 && n < 2.0:

{

Thread.Sleep(FAST_SLEEP_MSEC);

break;

}

default:

{

Thread.Sleep(DEFAULT_SLEEP_MSEC);

break;

}

}The setup of the experiment is as follows details of which can be found in the PolyGlot Notebook here.

open Optimization.Domain

open Optimization.Model

open Optimization.Charting

let iterations : int = 20

let resolution : int = 500

[<Literal>]

let workloadPath = @"..\..\src\Workloads\SimpleWorkload\bin\Release\net7.0\SimpleWorkload.exe"

let gaussianModelForSimpleWorkload() : GaussianModel =

let squaredExponentialKernelParameters : SquaredExponentialKernelParameters = { LengthScale = 1.0; Variance = 1.0 }

let gaussianProcess : GaussianProcess = createProcessWithSquaredExponentialKernel squaredExponentialKernelParameters

let queryProcessInfo : QueryProcessInfo = { WorkloadPath = workloadPath; ApplyArguments = (fun input -> $"--input {input}") }

let queryProcessObjectiveFunction : ObjectiveFunction = (QueryProcessByElapsedTimeInSeconds queryProcessInfo)

createModel gaussianProcess queryProcessObjectiveFunction ExpectedImprovement 0 5 resolution

let model : GaussianModel = gaussianModelForSimpleWorkload()

let optima : OptimaResults = findOptima { Model = model; Goal = Goal.Min; Iterations = iterations }

printfn "Optima: Simple Workload Time is minimized when the input is %A at %A seconds" optima.Optima.X optima.Optima.YThe result was: Optima: Simple Workload Time is minimized when the input is 1.372745491 at 0.13 seconds. This was a success as we force the main thread to sleep in the interval [1., 1.5) and the input: 1.37274591 is in that range!

A gif of the charted algorithm is:

The inputs here didn't require a highly precise resolution as the previous experiment and therefore, I set them to a moderately high amount of 500. I had to play around with the number of iterations as this was a more complex objective function in the eyes of the surrogate model; my strategy here was to start high and make my way to an acceptable amount. The other parameters i.e. Length Scale and Variance were the same, as before.

It's worth mentioning that the QueryProcessInfo type is used to specify the path to the workload and a mechanism to set the argument for the input we are pivoting on and is defined:

type QueryProcessInfo =

{

WorkloadPath : string

ApplyArguments : string -> string

}The workload code, that can be found here, first launches a separate process that induces a state of high memory; the source code for the high memory load inducer can be found here. Subsequently, a large number of allocations are intermittently made. While this workload is executing, we will have been taking a ETW Trace that'll contain the GC Pause Time %. The idea behind the experiment is to stress the memory of a machine and see how bursty allocations perform with varying Garbage Collection heaps the value of which, is controlled by 2 environment variables: COMPlus_GCHeapCount and COMPlus_GCServer where the former needs to be specified in Hexadecimal format indicating the number of heaps to be used bounded by the number of logical processors and the latter is a boolean (0 or 1).

The code to get this experiment going can be found here but the following are pertinent excerpts:

let iterations = System.Environment.ProcessorCount - 5

let resolution = System.Environment.ProcessorCount

let getHighMemoryBurstyAllocationsModel() : GaussianModel =

let gaussianProcess : GaussianProcess = createProcessWithSquaredExponentialKernel { LengthScale = 0.1; Variance = 1. }

let queryProcessByTraceLog : QueryProcessInfoByTraceLog =

{

WorkloadPath = WORKLOAD_PATH

ApplyArguments = (fun input -> "")

ApplyEnvironmentVariables = (fun input -> [("COMPlus_GCHeapCount", ( (int ( Math.Round(input))).ToString("X") )); ("COMPlus_GCServer", "1")] |> Map.ofList)

TraceLogApplication = (fun (traceLog : Microsoft.Diagnostics.Tracing.Etlx.TraceLog) ->

let eventSource : Microsoft.Diagnostics.Tracing.Etlx.TraceLogEventSource = traceLog.Events.GetSource()

eventSource.NeedLoadedDotNetRuntimes() |> ignore

eventSource.Process() |> ignore

let burstyAllocatorProcess : TraceProcess = eventSource.Processes() |> Seq.find(fun p -> p.Name.Contains "HighMemory_BurstyAllocations")

let managedProcess : TraceLoadedDotNetRuntime = burstyAllocatorProcess.LoadedDotNetRuntime()

managedProcess.GC.Stats().GetGCPauseTimePercentage()

)

TraceParameters = "/GCCollectOnly"

OutputPath = Path.Combine( basePath, "Traces" )

}

let queryProcessObjectiveFunction : ObjectiveFunction = QueryProcessByTraceLog queryProcessByTraceLog

createModelWithDiscreteInputs gaussianProcess queryProcessObjectiveFunction ExpectedImprovement 1 System.Environment.ProcessorCount resolution

let model : GaussianModel = getHighMemoryBurstyAllocationsModel()

let optima : OptimaResults = findOptima { Model = model; Goal = Goal.Min; Iterations = iterations }

printfn "Optima: GC Pause Time Percentage is minimized when the input is %A at %A" optima.Optima.X optima.Optima.YThe result of this experiment is: Optima: GC Pause Time Percentage is minimized when the input is 12.0 at 2.51148003.

And the gif of the charts is:

To validate these results, I did 2 things:

- Checked if the algorithm read the values correctly from the traces which, I confirmed by writing a simple command line program to do so:

// Experiments/HighMemoryBurstyAllocations/Program.fs

let pathsToTraces : string seq = Directory.GetFiles(Path.Combine(basePath, "Traces_15"), "*.etlx")

let getGCPauseTimePercentage(pathOfTrace : string) : double =

use traceLog : Microsoft.Diagnostics.Tracing.Etlx.TraceLog = new Microsoft.Diagnostics.Tracing.Etlx.TraceLog(pathOfTrace)

let eventSource : Microsoft.Diagnostics.Tracing.Etlx.TraceLogEventSource = traceLog.Events.GetSource()

eventSource.NeedLoadedDotNetRuntimes() |> ignore

eventSource.Process() |> ignore

let burstyAllocatorProcess : TraceProcess = eventSource.Processes() |> Seq.find(fun p -> p.Name.Contains "HighMemory_BurstyAllocations")

let managedProcess : TraceLoadedDotNetRuntime = burstyAllocatorProcess.LoadedDotNetRuntime()

managedProcess.GC.Stats().GetGCPauseTimePercentage()

pathsToTraces

|> Seq.iter(fun p -> (

printfn "Heap Count: %A - Percent Time in GC: %A" (Path.GetFileNameWithoutExtension(p)) (getGCPauseTimePercentage p)

))and confirmed that we did detect the minima:

| Heap Count | Percentage Pause Time In GC |

|---|---|

| "1" | 3.901133255 |

| "2" | 2.798426367 |

| "3" | 5.756154774 |

| "4" | 4.629494334 |

| "5" | 4.612814749 |

| "6" | 4.196522734 |

| "7" | 3.660711125 |

| "8" | 3.01808845 |

| "9" | 3.800542789 |

| "10" | 2.824685307 |

| "11" | 2.516458761 |

| "12" | 2.51148003 <- MIN |

| "13" | 2.710072749 |

| "14" | 2.522749182 |

| "15" | 2.556040017 |

| "16" | 3.506586409 |

- To confirm we were really at the global minima, I redid the experiment except this time, I set all the processors so that we iterated until the maximum number of processors on my machine (20) and got the following results:

Optima: GC Pause Time Percentage is minimized when the input is 12.0 at 2.247975719.

| Heap Count | Percentage Pause Time In GC |

|---|---|

| "1" | 4.7886298 |

| "2" | 4.236894341 |

| "3" | 4.71068455 |

| "4" | 3.870396061 |

| "5" | 4.460504767 |

| "6" | 3.473897596 |

| "7" | 3.276429007 |

| "8" | 3.203552845 |

| "9" | 2.846175963 |

| "10" | 2.563527965 |

| "11" | 2.434899728 |

| "12" | 2.247975719 <- MIN |

| "13" | 2.536508289 |

| "14" | 2.528864583 |

| "15" | 2.400874153 |

| "16" | 2.362189349 |

| "17" | 3.375737401 |

| "18" | 5.864851149 |

| "19" | 5.352540323 |

| "20" | 6.907995823 |

Since the minima was close to 16, we can confirm the validity of the experiment that is also susceptible to non-determinism because of the Garbage Collector, state of the machine at the time of taking the traces and other reasons.

ETW provides a way to capture traces that comprise of structured log messages raised either by User or Kernel Providers that generate these log messages. The specific provider we relied for the previous experiment was that of the CLR that aggregated the data in a clean way to get us the details for the Percentage Pause Time spent in the GC.

A trace can be captured via the command line using PerfView or PerfCollect, a performance analysis and trace capturing tool.

As an example, to start a trace for Experiment 3, I used the following command line:

PerfView.exe start /GCCollectOnly /NoGUI /AcceptEULA collect trace

and to stop:

PerfView.exe stop /GCCollectOnly /NoGUI /AcceptEULA collect trace

/GCCollectOnlyis a special keyword that captures a minimal form the trace with GC specific messages that are sufficient to highlight the GC centric performance of a particular workload.collectis the command to collect a tracetraceis the name of the trace file being saved. This will by default result in a.etl.zipfile.- The other

/NoGUIand/AcceptEULAparameters are to not start the PerfView GUI and to prevent the EULA dialog box from popping up and impeding our ability to capture a trace, respectively.

A trace can be programmatically analyzed using the Trace Event Library and the most comprehensive documentation that goes over details of this can be found here.

The example in Experiment 3 made use of the TraceLog API that converts an ETL file to the more bolstered ETLX file from which we can access the process specific GC metrics.

The three components, as mentioned above, of the Bayesian Optimization algorithm are the Surrogate Model, Acquisition Function and the Iteration Loop. To reiterate, the surrogate model, as hinted to by the name, is a model that serves as an approximation of the objective function while the acquisition function guides where the algorithm should search next where the best observation is most likely to reach the global optima and the iteration loop facilitates the maximization of the acquisition function on the basis of the predictions made by the surrogate model thereby presenting the next point to sample.

To go over the preliminary parts of the domain, we first have a concept of a Goal which, is implemented as a Discriminated Union of a choice of minimization or maximization of the objective function.

// src/Optimization.Core/Domain.fs

type Goal =

| Max

| MinNext, the Observed Data Points by way of which we deduce the optima is defined as a record type:

// src/Optimization.Core/Domain.fs

type DataPoint = { X : double; Y : double }Our main function that kicks off the optimization is modeled in the following way:

// src/Optimization.Core/Model.fs

let findOptima (request : OptimizationRequest) : OptimaResult =

// Optimize!where OptimizationRequest and OptimaResult are defined as:

// src/Optimization.Core/Domain.fs

type OptimizationRequest =

{

Model : GaussianModel

Goal : Goal

Iterations : int

}

type OptimaResult =

{

ExplorationResults : ExplorationResults

Optima : DataPoint

}Now that we have set the stage of the definitions of the major components of the model, we can get more specific.

A number of techniques can be used to represent the surrogate model however, one of the most popular ways to do so is to use Gaussian Processes that are defined as the following to be used in the GaussianModel record type above:

and GaussianProcess =

{

KernelFunction : KernelFunction

ObservedDataPoints : List<DataPoint>

mutable CovarianceMatrix : Matrix<double>

}and since we are using Gaussian Processes for this implementation, a Gaussian Model seemed like an apt name and is defined as and used above in the OptimizationRequest:

type GaussianModel =

{

GaussianProcess : GaussianProcess

ObjectiveFunction : ObjectiveFunction

Inputs : double list

AcquisitionFunction : AcquisitionFunction

}A Gaussian Process is a random process comprising of a collection of random variables such that the joint probability distribution of every subset of these random variables is normally distributed. Intuitively, a Gaussian Process can be thought of a possibly infinite set of normally distributed variables that excel at efficient and effective summarization of a large number of functions and smooth transitions as more data is available to the model.

There are two important details that describe a particular Gaussian Process: Mean Function dictating the mean or centeredness of the individual random variables and the Covariance Matrix that dictates the shape.

An important aspect of defining a Gaussian Process is the Kernel that controls the shape of the function at specific points by changing the Covariance Matrix based on the definition and the parameters supplied. The kernel I have implemented is called the "Squared Exponential Kernel" or "Gaussian Kernel" and has two parameters that control the smoothness of the function via a length parameter and vertical variation via a variance parameter.

The code of this function looks like the following where left and right are the two points for which we get details about the shape of the function at hand.

// src/Optimization.Core/Kernel.fs

let squaredExponentialKernelCompute (parameters : SquaredExponentialKernelParameters) (left : double) (right : double) : double =

if left = right then parameters.Variance

else

let squareDistance : double = Math.Pow((left - right), 2)

parameters.Variance * Math.Exp( -squareDistance / ( parameters.LengthScale * parameters.LengthScale * 2. ))where the SquaredExponentialKernelParameters are defined as:

// src/Optimization.Core/Domain.fs

type SquaredExponentialKernelParameters = { LengthScale : double; Variance : double }More details about the choice of this kernel can be found here.

Mathematically,

With:

-

$σ^2$ the overall variance is also known as amplitude or the vertical variance. -

$\ell$ the length scale gives us the smoothness between the two points.

To allow more kernels to be defined, we define the KernelFunction type as:

//src/Optimization.Core/Domain.fs

// Kernel Function.

and KernelFunction =

| SquaredExponentialKernel of SquaredExponentialKernelParameterswhere we have the ability to add more cases. We pattern match on the type of kernel in a separate function and use partial application to make use of the kernel function as and when the parameters are applied.

// src/Optimization.Core/Kernel.fs

// I ♥ Partial Application.

let getKernelFunction (model : GaussianModel) : double -> double -> double =

match model.GaussianProcess.KernelFunction with

| SquaredExponentialKernel parameters ->

squaredExponentialKernelCompute parametersFitting the Gaussian Process Model entails we reconstruct the Covariance Matrix with the latest data by using the specified Kernel. The code for this looks like the following (cleaned up for simplicity) where we compute the output from the objective function, add the new point to the observations and reconstruct the covariance matrix by way of the kernel function:

// src/Optimization.Core/Model.fs

let result : double =

match model.ObjectiveFunction with

| QueryContinuousFunction queryFunction -> queryFunction input

| QueryProcessByElapsedTimeInSeconds queryProcessInfo -> queryProcessByElapsedTimeInSeconds queryProcessInfo input

| QueryProcessByTraceLog queryProcessInfo -> queryProcessByTraceLog queryProcessInfo input

let matchedKernel : double -> double -> double = getKernelFunction model

let dataPoint : DataPoint = { X = input; Y = result }

model.GaussianProcess.ObservedDataPoints.Add dataPoint

let size : int = model.GaussianProcess.ObservedDataPoints.Count

let mutable updatedCovarianceMatrix : Matrix<double> = Matrix<double>.Build.Dense(size, size)

// Copy over the contents of the current covariance matrix.

for rowIdx in 0..(model.GaussianProcess.CovarianceMatrix.RowCount - 1) do

for columnIdx in 0..(model.GaussianProcess.CovarianceMatrix.ColumnCount - 1) do

updatedCovarianceMatrix[rowIdx, columnIdx] <- model.GaussianProcess.CovarianceMatrix.[rowIdx, columnIdx]

// Compute values of the new point.

for iteratorIdx in 0..(size - 1) do

let modelValueAtIndex : double = model.GaussianProcess.ObservedDataPoints.[iteratorIdx].X

let value : double = matchedKernel modelValueAtIndex dataPoint.X

updatedCovarianceMatrix[iteratorIdx, size - 1] <- value

updatedCovarianceMatrix[size - 1, iteratorIdx] <- value

updatedCovarianceMatrix[size - 1, size - 1] <- matchedKernel dataPoint.X dataUsing the Gaussian Process Model to make predictions essentially means we are generating and sampling the posterior to give us the mean and confidence levels about our sample (This is very Bayesian in contrast to just returning a single point). The output of the prediction is modeled in the following way:

// src/Optimization.Core/Domain.fs

type PredictionResult =

{

Input : double

Mean : double

LowerBound : double

UpperBound : double

}The Linear Algebra involved is that of computing the posterior using the observed data and inputs that the model was initialized with i.e. the priors which, in our case were set based on the range and the resolution:

// src/Optimization.Core/Model.fs

let matchedKernelFunction : (double -> double -> double) = getKernelFunction model

let kStar : double[] =

gaussianProcess.ObservedDataPoints

.Select(fun dp -> matchedKernelFunction input dp.X)

.ToArray()

let yTrain : double[] =

gaussianProcess.ObservedDataPoints

.Select(fun dp -> dp.Y)

.ToArray()

let ks : Vector<double> = Vector<double>.Build.Dense kStar

let f : Vector<double> = Vector<double>.Build.Dense yTrain

// Common helper term.

let common : Vector<double> = gaussianProcess.CovarianceMatrix.Inverse().Multiply ks

// muStar = Kstar^T * K^-1 * f = common dot f

let mu : double = common.DotProduct f

let confidence : double = Math.Abs( matchedKernelFunction input input - common.DotProduct(ks) )

{ Mean = mu; LowerBound = mu - confidence; UpperBound = mu + confidence; Input = input }A more in-depth tutorial on the posterior calculation that leads to the prediction computation can be found here. The explanation there will probably be better than any I can give and despite the seemingly complexity of the linear algebra, at the end of the day, we are applying Bayes Theorem to multivariate normally distributed variables.

Where to sample next within the specified range is dictated by the acquisition function. This function conducts a trade off between "Exploitation and Exploration". Exploitation means we are sampling or choosing points where the surrogate model is know to produce high objective function result. Exploration means we are sampling or choosing points we haven't explored before or where the prediction uncertainty is high. The point where the acquisition function is maximized is the next point to sample.

A very popular acquisition function is called "Expected Improvement (EI)" and is given by:

and can be modeled as:

// src/Optimization.Core/AcquisitionFunction.fs

type AcquisitionFunction =

| ExpectedImprovement

and AcquisitionFunctionRequest =

{

GaussianProcess : GaussianProcess

PredictionResult : PredictionResult

Goal : Goal

}

and AcquisitionFunctionResult = { Input : double; AcquisitionScore: double }and the analytic solution using a Gaussian Process of this is as follows:

// src/Optimization.Core/AcquisitionFunction.fs

let Δ : double = predictionResult.Mean - optimumValue - explorationParameter

let σ : double = (predictionResult.UpperBound - predictionResult.LowerBound) / 2.

let z : double = Δ / σ

let exploitationFactor : double = Δ * Normal.CDF(0, 1, z)

let explorationFactor : double = σ * Normal.PDF(0, 1, z)

let expectedImprovement : double = exploitationFactor + explorationFactorThe idea here is that based on the predicted result from the surrogate function, we compute an exploitation and exploration factor and sum the two to give us the most statistically sound place to sample next balancing both exploitation and exploration.

As described above, in the bayesian optimization loop we do the following:

- Make predictions using the surrogate model.

- Based on the predictions from 1., apply the acquisition function.

- Identify the point that maximizes the acquisition function.

- Update the model with the new data point.

In addition to these steps, we are also keeping track of the intermediate steps of the calculation to help with visualizing the results.

// src/Optimization.Core/Model.fs

// Iterate with each step to find the most optimum next point.

seq { 0..(request.Iterations - 1) }

|> Seq.iter(fun iteration -> (

// Select next point to sample via the surrogate function i.e. estimation of the objective that maximizes the acquisition function.

let predictions : PredictionResult seq = predict model

let acquisitionResults : AcquisitionFunctionResult seq = predictions.Select(fun predictionResult -> applyAcquisitionFunction predictionResult)

let optimumValueFromAcquisition : AcquisitionFunctionResult = acquisitionResults.MaxBy(fun e -> e.AcquisitionScore)

let nextPoint : double = optimumValueFromAcquisition.Input

// Copy the state of the ObservedDataPoints for this iteration.

let copyBuffer : DataPoint[] = Array.zeroCreate model.GaussianProcess.ObservedDataPoints.Count

model.GaussianProcess.ObservedDataPoints.CopyTo(copyBuffer) |> ignore

let result : ModelResult =

{

ObservedDataPoints = copyBuffer.ToList()

AcquisitionResults = acquisitionResults.ToList()

PredictionResults = predictions.ToList()

}

intermediateResults.Add({ Result = result; NextPoint = nextPoint; Iteration = iteration })

// Add the point to the model if it already hasn't been added.

if model.GaussianProcess.ObservedDataPoints.Any(fun d -> d.X = nextPoint) then ()

else applyFitToModel nextPoint

))And there we have it! There is of course room for significant amount of improvement here such as:

- Adding early stopping if we aren't making much progress with each subsequent iteration.

- Adding the ability to optimize multiple variables.

- Adding report generation based on the intermediate results.

Using F# for this project has been nothing short of awesome! After working on these submissions, I am usually left questioning why I don't use F# more often. Even though I didn't use the plethora of features the language has to offer, I lucidly accomplished what I intended to set out to accomplish; I believe the ease with which I was able to get things done is testament to strength of the language that keeps me coming back for more!

Domain Modeling using Discriminated Unions and Record Types, Pattern Matching and Partial Application are the 3 of my favorite features I had the most fun using. My favorite functional programming concept is one of the core ones: how composing functions with other functions is a simple yet powerful foundation to build complex features on.

As always, I am super open to feedback as to how I have made use of F# developing this project and so, if anyone has suggestions of how I could developed this any better, I am all ears!

It has been 6 years of submissions to the FSharp Advent event and it has been an awesome experience. Here are links to my previous posts:

- 2021: Perf Avore: A Performance Analysis and Monitoring Tool in FSharp

- 2020: Bayesian Inference in F#

- 2019: Building A Simple Recommendation System in F#

- 2018: An Introduction to Probabilistic Programming in F#

- 2017: The Lord of The Rings: An F# Approach

Phew! That was quite a bit of information! I had a fantastic time working on this (still continuing) project and learning about the internals of the Bayesian Optimization Algorithm. To reiterate, we covered:

- Details About the Bayesian Optimization Algorithm

- 3 Experimental Usages of the Library I developed that Implemented this.

- Gave a primer on ETW events.

- Described details of the implementation.

Thanks goes out to: Pavel Koryakin whose repository gave me a perfectly apt place to start with developing my own and Sergey Tihon for organizing the FSharp Advent event.

Happy Holidays to All!