Mu is a minimal-dependency hobbyist computing stack (everything above the processor).

Mu is not designed to operate in large clusters providing services for millions of people. Mu is designed for you, to run one computer. (Or a few.) Running the code you want to run, and nothing else.

Here's the Mu computer running Conway's Game of Life.

git clone https://github.com/akkartik/mu

cd mu

./translate life.mu # emit a bootable code.img

qemu-system-i386 code.img(Colorized sources. This is memory-safe code, and most statements map to a single instruction of machine code.)

Rather than start from some syntax and introduce layers of translation to implement it, Mu starts from the processor's instruction set and tries to get to some safe and clear syntax with as few layers of translation as possible. The emphasis is on internal consistency at any point in time rather than compatibility with the past. (More details.)

Tests are a key mechanism here for creating a computer that others can make their own. I want to encourage a style of active and interactive reading with Mu. If something doesn't make sense, try changing it and see what tests break. Any breaking change should cause a failure in some well-named test somewhere.

Currently Mu requires a 32-bit x86 processor.

In priority order:

- Reward curiosity.

- Easy to build, easy to run. Minimal dependencies, so that installation is always painless.

- All design decisions comprehensible to a single individual. (On demand.)

- All design decisions comprehensible without needing to talk to anyone. (I always love talking to you, but I try hard to make myself redundant.)

- A globally comprehensible codebase rather than locally clean code.

- Clear error messages over expressive syntax.

- Safe.

- Thorough test coverage. If you break something you should immediately see an error message. If you can manually test for something you should be able to write an automated test for it.

- Memory leaks over memory corruption.

- Teach the computer bottom-up.

Thorough test coverage in particular deserves some elaboration. It implies that any manual test should be easy to turn into a reproducible automated test. Mu has some unconventional methods for providing this guarantee. It exposes testable interfaces for hardware using dependency injection so that tests can run on -- and make assertions against -- fake hardware. It also performs automated white-box testing which enables robust tests for performance, concurrency, fault-tolerance, etc.

- Speed. Staying close to machine code should naturally keep Mu fast enough.

- Efficiency. Controlling the number of abstractions should naturally keep Mu using far less than the gigabytes of memory modern computers have.

- Portability. Mu will run on any computer as long as it's x86. I will enthusiastically contribute to support for other processors -- in separate forks. Readers shouldn't have to think about processors they don't have.

- Compatibility. The goal is to get off mainstream stacks, not to perpetuate them. Sometimes the right long-term solution is to bump the major version number.

- Syntax. Mu code is meant to be comprehended by running, not just reading. For now it's a thin memory-safe veneer over machine code. I'm working on a high-level "shell" for the Mu computer.

The Mu stack consists of:

- the Mu type-safe and memory-safe language;

- SubX, an unsafe notation for a subset of x86 machine code; and

- bare SubX, a more rudimentary form of SubX without certain syntax sugar.

All Mu programs get translated through these layers into tiny zero-dependency binaries that run natively. The translators for most levels are built out of lower levels. The translator from Mu to SubX is written in SubX, and the translator from SubX to bare SubX is built in bare SubX. There is also an emulator for Mu's supported subset of x86, that's useful for debugging SubX programs.

Mu programs build natively either on Linux or on Windows using WSL 2. For Macs and other Unix-like systems, use the (much slower) emulator:

./translate_emulated ex2.mu # ~2 mins to emit code.imgMu programs can be written for two very different environments:

-

At the top-level, Mu programs emit a bootable image that runs without an OS (under emulation; I haven't tested on native hardware yet). There's rudimentary support for some core peripherals: a 1024x768 screen, a keyboard with some key-combinations, a PS/2 mouse that must be polled, a slow ATA disk drive. No hardware acceleration, no virtual memory, no process separation, no multi-tasking, no network. Boot always runs all tests, and only gets to

mainif all tests pass. -

The top-level is built using tools created under the

linux/sub-directory. This sub-directory contains an entirely separate set of libraries intended for building programs that run with just a Linux kernel, reading from stdin and writing to stdout. The Mu compiler is such a program, atlinux/mu.subx. Individual programs typically run tests if given a command-line argument calledtest.

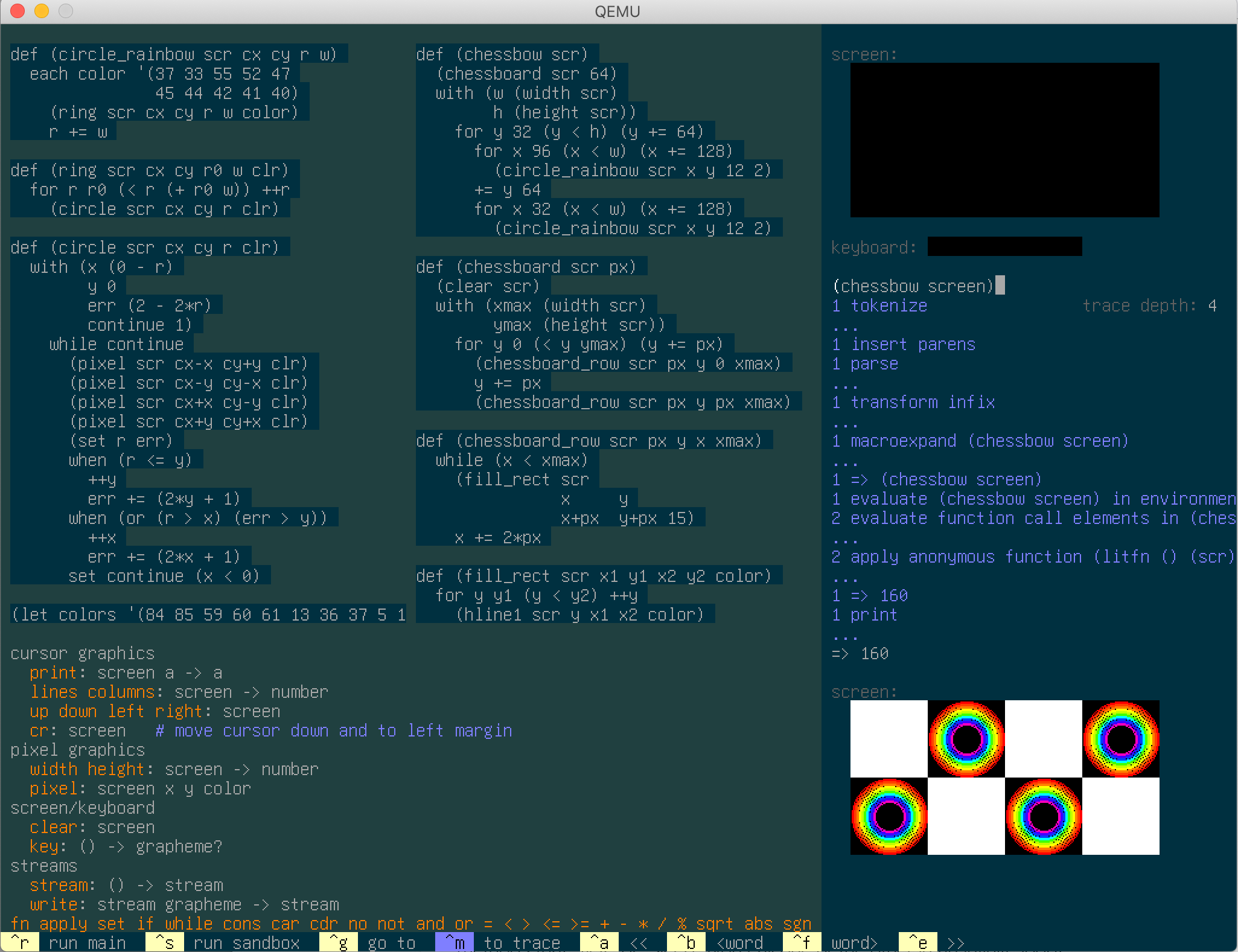

The largest program built in Mu today is its prototyping environment for writing slow, interpreted programs in a Lisp-based high-level language.

(For more details, see the shell/ directory.)

While I currently focus on programs without an OS, the linux/ sub-directory

is fairly ergonomic. There's a couple of dozen example programs to try out

there. It is likely to be the option for a network stack in the foreseeable

future; I have no idea how to interact on the network without Linux.

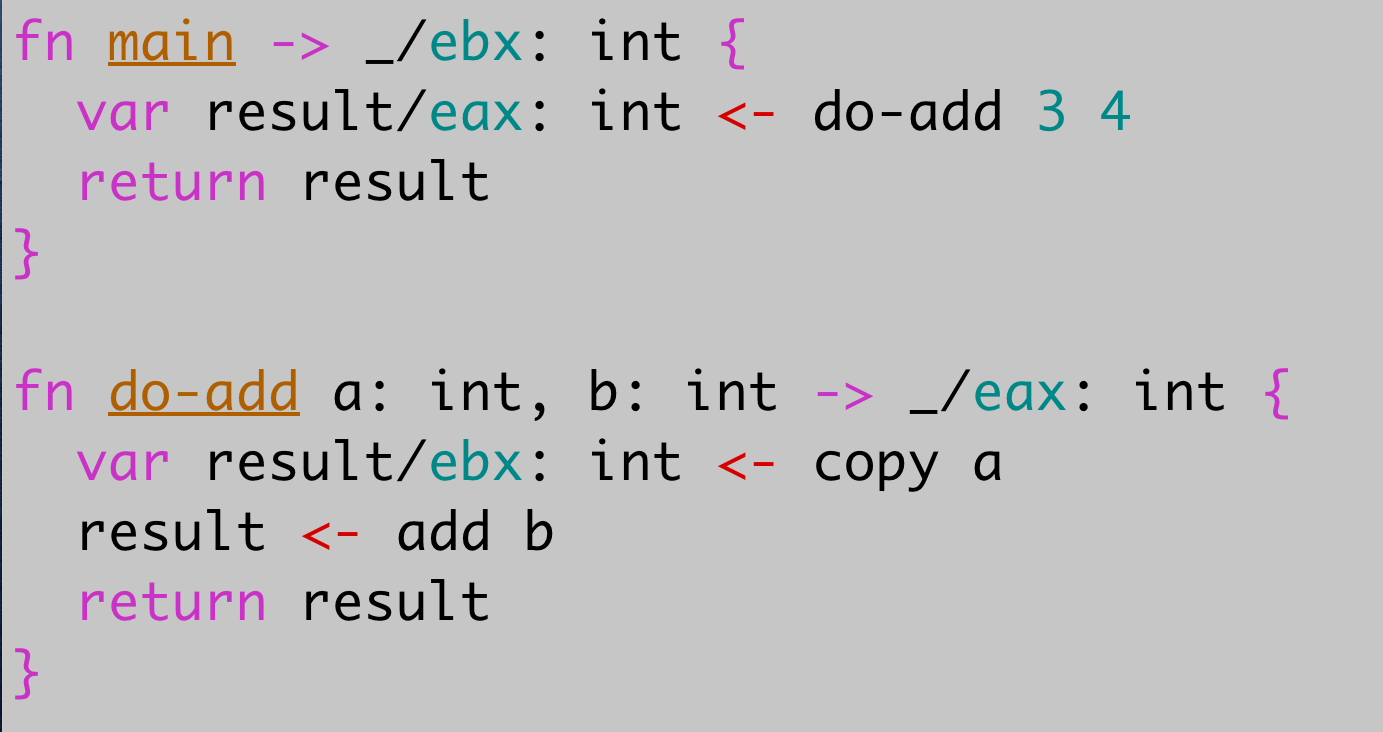

The entire stack shares certain properties and conventions. Programs consist

of functions and functions consist of statements, each performing a single

operation. Operands to statements are always variables or constants. You can't

perform a + b*c in a single statement; you have to break it up into two.

Variables can live in memory or in registers. Registers must be explicitly

specified. There are some shared lexical rules. Comments always start with

'#'. Numbers are always written in hex. Many terms can have context-dependent

metadata attached after '/'.

Here's an example program in Mu:

More resources on Mu:

-

Library reference. Mu programs can transparently call low-level functions written in SubX.

Here's an example program in SubX:

== code

Entry:

# ebx = 1

bb/copy-to-ebx 1/imm32

# increment ebx

43/increment-ebx

# exit(ebx)

e8/call syscall_exit/disp32More resources on SubX:

-

Some starter exercises for learning SubX (labelled

hello). Feel free to ping me with any questions. -

The list of x86 opcodes supported in SubX:

linux/bootstrap/bootstrap help opcodes.

Forks of Mu are encouraged. If you don't like something about this repo, feel free to make a fork. If you show it to me, I'll link to it here. I might even pull features upstream!

- uCISC: a 16-bit processor being designed from scratch by Robert Butler and programmed with a SubX-like syntax.

- subv: experimental SubX-like syntax by s-ol bekic for the RISC-V instruction set.

- mu-x86_64: experimental fork for 64-bit x86 in collaboration with Max Bernstein. It's brought up a few concrete open problems that I don't have good solutions for yet.

- mu-normie: with a more standard

build system for the

linux/bootstrap/directory that organizes the repo by header files and compilation units. Stays in sync with this repo.

If you're still reading, here are some more things to check out:

-

How to get your text editor set up for Mu and SubX programs.

-

A summary of how the Mu compiler translates statements to SubX. Most Mu statements map to a single x86 instruction. (colorized version)

-

A prototype live-updating programming environment for a postfix language that I might work on again one day:

cd linux ./translate tile/*.mu ./a.elf screen

Mu builds on many ideas that have come before, especially:

- Peter Naur for articulating the paramount problem of programming: communicating a codebase to others;

- Christopher Alexander and Richard Gabriel for the intellectual tools for reasoning about the higher order design of a codebase;

- David Parnas and others for highlighting the value of separating concerns and stepwise refinement;

- The folklore of debugging by print and the trace facility in many Lisp systems;

- Automated tests for showing the value of developing programs inside an elaborate harness;

On a more tactical level, this project has made progress in a series of bursts as I discovered the following resources. In autobiographical order, with no claims of completeness:

- “Bootstrapping a compiler from nothing” by Edmund Grumley-Evans.

- StoneKnifeForth by Kragen Sitaker, including a tiny sketch of an ELF loader.

- “Creating tiny ELF executables” by Brian Raiter.

- Single-page cheatsheet for the x86 ISA by Daniel Plohmann (cached local copy)

- Minimal Linux Live for teaching how to create a bootable disk image using the syslinux bootloader.

- “Writing a bootloader from scratch” by Nick Blundell.

- Wikipedia on BIOS interfaces: Int 10h, Int 13h.

- Some tips on programming bootloaders by Michael Petch.

- xv6, the port of Unix Version 6 to x86 processors

- Some tips on handling keyboard interrupts by Alex Dzyoba and Michael Petch.