Creating a :app:`Pyramid` Project

As we saw in :ref:`firstapp_chapter`, it's possible to create a :app:`Pyramid` application completely manually. However, it's usually more convenient to use a :term:`scaffold` to generate a basic :app:`Pyramid` :term:`project`.

A project is a directory that contains at least one Python :term:`package`. You'll use a scaffold to create a project, and you'll create your application logic within a package that lives inside the project. Even if your application is extremely simple, it is useful to place code that drives the application within a package, because: 1) a package is more easily extended with new code and 2) an application that lives inside a package can also be distributed more easily than one which does not live within a package.

:app:`Pyramid` comes with a variety of scaffolds that you can use to generate a project. Each scaffold makes different configuration assumptions about what type of application you're trying to construct.

These scaffolds are rendered using the pcreate command that is installed

as part of Pyramid.

.. index:: single: scaffolds single: starter scaffold single: zodb scaffold single: alchemy scaffold

Scaffolds Included with :app:`Pyramid`

The convenience scaffolds included with :app:`Pyramid` differ from each other on a number of axes:

- the persistence mechanism they offer (no persistence mechanism, :term:`ZODB`, or :term:`SQLAlchemy`).

- the mechanism they use to map URLs to code (:term:`traversal` or :term:`URL dispatch`).

The included scaffolds are these:

starter- URL mapping via :term:`URL dispatch` and no persistence mechanism.

zodb- URL mapping via :term:`traversal` and persistence via :term:`ZODB`. Note that, as of this writing, this scaffold will not run under Python 3, only under Python 2.

alchemy- URL mapping via :term:`URL dispatch` and persistence via :term:`SQLAlchemy`

.. index:: single: creating a project single: project

In :ref:`installing_chapter`, you created a virtual Python environment via

the virtualenv command. To start a :app:`Pyramid` :term:`project`, use

the pcreate command installed within the virtualenv. We'll choose the

starter scaffold for this purpose. When we invoke pcreate, it will

create a directory that represents our project.

In :ref:`installing_chapter` we called the virtualenv directory env; the

following commands assume that our current working directory is the env

directory.

On UNIX:

$ $VENV/bin/pcreate -s starter MyProject

Or on Windows:

> %VENV%\Scripts\pcreate -s starter MyProject

The above command uses the pcreate command to create a project with the

starter scaffold. To use a different scaffold, such as

alchemy, you'd just change the -s argument value. For example,

on UNIX:

$ $VENV/bin/pcreate -s alchemy MyProject

Or on Windows:

> %VENV%\Scripts\pcreate -s alchemy MyProject

Here's sample output from a run of pcreate on UNIX for a project we name

MyProject:

$ $VENV/bin/pcreate -s starter MyProject

Creating template pyramid

Creating directory ./MyProject

# ... more output ...

Running /Users/chrism/projects/pyramid/bin/python setup.py egg_info

As a result of invoking the pcreate command, a directory named

MyProject is created. That directory is a :term:`project` directory.

The setup.py file in that directory can be used to distribute your

application, or install your application for deployment or development.

A .ini file named development.ini will be created in the project

directory. You will use this .ini file to configure a server, to run

your application, and to debug your application. It contains configuration

that enables an interactive debugger and settings optimized for development.

Another .ini file named production.ini will also be created in the

project directory. It contains configuration that disables any interactive

debugger (to prevent inappropriate access and disclosure), and turns off a

number of debugging settings. You can use this file to put your application

into production.

The MyProject project directory contains an additional subdirectory named

myproject (note the case difference) representing a Python

:term:`package` which holds very simple :app:`Pyramid` sample code. This is

where you'll edit your application's Python code and templates.

We created this project within an env virtualenv directory. However,

note that this is not mandatory. The project directory can go more or less

anywhere on your filesystem. You don't need to put it in a special "web

server" directory, and you don't need to put it within a virtualenv

directory. The author uses Linux mainly, and tends to put project

directories which he creates within his ~/projects directory. On

Windows, it's a good idea to put project directories within a directory that

contains no space characters, so it's wise to avoid a path that contains

i.e. My Documents. As a result, the author, when he uses Windows, just

puts his projects in C:\projects.

Warning

You’ll need to avoid using pcreate to create a project with the same

name as a Python standard library component. In particular, this means you

should avoid using the names site or test, both of which

conflict with Python standard library packages. You should also avoid

using the name pyramid, which will conflict with Pyramid itself.

.. index:: single: setup.py develop single: development install

To install a newly created project for development, you should cd to the

newly created project directory and use the Python interpreter from the

:term:`virtualenv` you created during :ref:`installing_chapter` to invoke the

command python setup.py develop

The file named setup.py will be in the root of the pcreate-generated

project directory. The python you're invoking should be the one that

lives in the bin (or Scripts on Windows) directory of your virtual

Python environment. Your terminal's current working directory must be the

newly created project directory.

On UNIX:

$ cd MyProject

$ $VENV/bin/python setup.py develop

Or on Windows:

> cd MyProject

> %VENV%\Scripts\python.exe setup.py develop

Elided output from a run of this command on UNIX is shown below:

$ cd MyProject

$ $VENV/bin/python setup.py develop

...

Finished processing dependencies for MyProject==0.0

This will install a :term:`distribution` representing your project into the

interpreter's library set so it can be found by import statements and by

other console scripts such as pserve, pshell, proutes and

pviews.

.. index:: single: running tests single: tests (running)

To run unit tests for your application, you should invoke them using the

Python interpreter from the :term:`virtualenv` you created during

:ref:`installing_chapter` (the python command that lives in the bin

directory of your virtualenv).

On UNIX:

$ $VENV/bin/python setup.py test -q

Or on Windows:

> %VENV%\Scripts\python.exe setup.py test -q

Here's sample output from a test run on UNIX:

$ $VENV/bin/python setup.py test -q

running test

running egg_info

writing requirements to MyProject.egg-info/requires.txt

writing MyProject.egg-info/PKG-INFO

writing top-level names to MyProject.egg-info/top_level.txt

writing dependency_links to MyProject.egg-info/dependency_links.txt

writing entry points to MyProject.egg-info/entry_points.txt

reading manifest file 'MyProject.egg-info/SOURCES.txt'

writing manifest file 'MyProject.egg-info/SOURCES.txt'

running build_ext

..

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Ran 1 test in 0.108s

OK

Note

The -q option is passed to the setup.py test command to limit the

output to a stream of dots. If you don't pass -q, you'll see more

verbose test result output (which normally isn't very useful).

The tests themselves are found in the tests.py module in your pcreate

generated project. Within a project generated by the starter scaffold, a

single sample test exists.

.. index:: single: running an application single: pserve single: reload single: startup

Once a project is installed for development, you can run the application it

represents using the pserve command against the generated configuration

file. In our case, this file is named development.ini.

On UNIX:

$ $VENV/bin/pserve development.ini

On Windows:

> %VENV%\Scripts\pserve development.ini

Here's sample output from a run of pserve on UNIX:

$ $VENV/bin/pserve development.ini

Starting server in PID 16601.

serving on http://0.0.0.0:6543

When you use pserve to start the application implied by the default

rendering of a scaffold, it will respond to requests on all IP addresses

possessed by your system, not just requests to localhost. This is what

the 0.0.0.0 in serving on http://0.0.0.0:6543 means. The server will

respond to requests made to 127.0.0.1 and on any external IP address.

For example, your system might be configured to have an external IP address

192.168.1.50. If that's the case, if you use a browser running on the

same system as Pyramid, it will be able to access the application via

http://127.0.0.1:6543/ as well as via

http://192.168.1.50:6543/. However, other people on other computers on

the same network will also be able to visit your Pyramid application in their

browser by visiting http://192.168.1.50:6543/.

If you want to restrict access such that only a browser running on the same

machine as Pyramid will be able to access your Pyramid application, edit the

development.ini file, and replace the host value in the

[server:main] section. Change it from 0.0.0.0 to 127.0.0.1. For

example:

[server:main]

use = egg:waitress#main

host = 127.0.0.1

port = 6543You can change the port on which the server runs on by changing the same

portion of the development.ini file. For example, you can change the

port = 6543 line in the development.ini file's [server:main]

section to port = 8080 to run the server on port 8080 instead of

port 6543.

You can shut down a server started this way by pressing Ctrl-C.

The default server used to run your Pyramid application when a project is

created from a scaffold is named :term:`Waitress`. This server is what

prints the serving on... line when you run pserve. It's a good idea

to use this server during development, because it's very simple. It can also

be used for light production. Setting your application up under a different

server is not advised until you've done some development work under the

default server, particularly if you're not yet experienced with Python web

development. Python web server setup can be complex, and you should get some

confidence that your application works in a default environment before trying

to optimize it or make it "more like production". It's awfully easy to get

sidetracked trying to set up a nondefault server for hours without actually

starting to do any development. One of the nice things about Python web

servers is that they're largely interchangeable, so if your application works

under the default server, it will almost certainly work under any other

server in production if you eventually choose to use a different one. Don't

worry about it right now.

For more detailed information about the startup process, see :ref:`startup_chapter`. For more information about environment variables and configuration file settings that influence startup and runtime behavior, see :ref:`environment_chapter`.

During development, it's often useful to run pserve using its

--reload option. When --reload is passed to pserve, changes to

any Python module your project uses will cause the server to restart. This

typically makes development easier, as changes to Python code made within a

:app:`Pyramid` application is not put into effect until the server restarts.

For example, on UNIX:

$ $VENV/bin/pserve development.ini --reload

Starting subprocess with file monitor

Starting server in PID 16601.

serving on http://0.0.0.0:6543

Now if you make a change to any of your project's .py files or .ini

files, you'll see the server restart automatically:

development.ini changed; reloading...

-------------------- Restarting --------------------

Starting server in PID 16602.

serving on http://0.0.0.0:6543

Changes to template files (such as .pt or .mak files) won't cause the

server to restart. Changes to template files don't require a server restart

as long as the pyramid.reload_templates setting in the

development.ini file is true. Changes made to template files when

this setting is true will take effect immediately without a server restart.

.. index:: single: WSGI

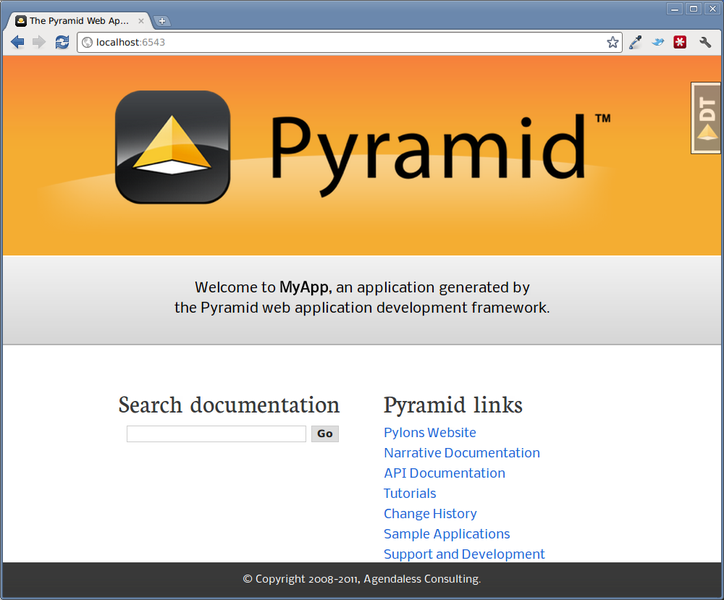

Once your application is running via pserve, you may visit

http://localhost:6543/ in your browser. You will see something in your

browser like what is displayed in the following image:

This is the page shown by default when you visit an unmodified pcreate

generated starter application in a browser.

.. index:: single: debug toolbar

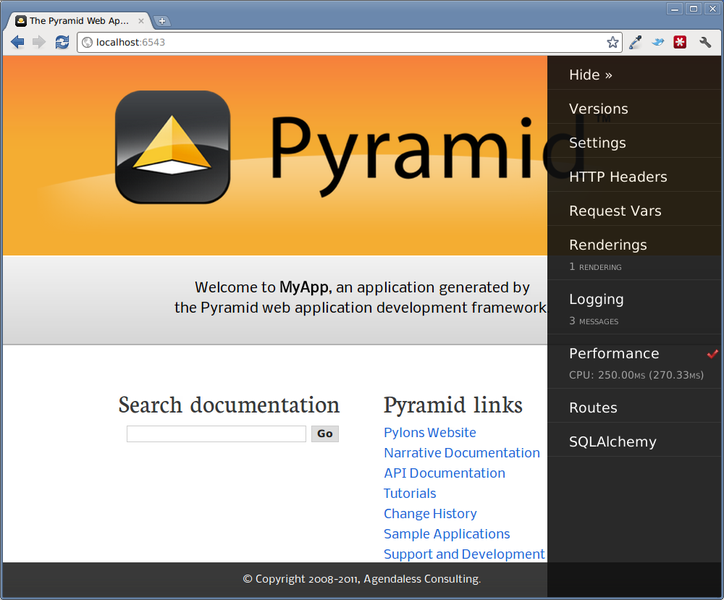

If you click on the image shown at the right hand top of the page ("^DT"),

you'll be presented with a debug toolbar that provides various niceties while

you're developing. This image will float above every HTML page served by

:app:`Pyramid` while you develop an application, and allows you show the

toolbar as necessary. Click on Hide to hide the toolbar and show the

image again.

If you don't see the debug toolbar image on the right hand top of the page,

it means you're browsing from a system that does not have debugging access.

By default, for security reasons, only a browser originating from

localhost (127.0.0.1) can see the debug toolbar. To allow your

browser on a remote system to access the server, add a line within the

[app:main] section of the development.ini file in the form

debugtoolbar.hosts = X.X.X.X. For example, if your Pyramid application

is running on a remote system, and you're browsing from a host with the IP

address 192.168.1.1, you'd add something like this to enable the toolbar

when your system contacts Pyramid:

[app:main]

# .. other settings ...

debugtoolbar.hosts = 192.168.1.1For more information about what the debug toolbar allows you to do, see the documentation for pyramid_debugtoolbar.

The debug toolbar will not be shown (and all debugging will be turned off)

when you use the production.ini file instead of the development.ini

ini file to run the application.

You can also turn the debug toolbar off by editing development.ini and

commenting out a line. For example, instead of:

[app:main]

...

pyramid.includes =

pyramid_debugtoolbarPut a hash mark at the beginning of the pyramid_debugtoolbar line:

[app:main]

...

pyramid.includes =

# pyramid_debugtoolbarThen restart the application to see that the toolbar has been turned off.

Note that if you comment out the pyramid_debugtoolbar line, the #

must be in the first column. If you put it anywhere else,

and then attempt to restart the application,

you'll receive an error that ends something like this:

ImportError: No module named #pyramid_debugtoolbar

.. index:: single: project structure

The starter scaffold generated a :term:`project` (named MyProject),

which contains a Python :term:`package`. The package is also named

myproject, but it's lowercased; the scaffold generates a project which

contains a package that shares its name except for case.

All :app:`Pyramid` pcreate -generated projects share a similar structure.

The MyProject project we've generated has the following directory

structure:

MyProject/

|-- CHANGES.txt

|-- development.ini

|-- MANIFEST.in

|-- myproject

| |-- __init__.py

| |-- static

| | |-- favicon.ico

| | |-- logo.png

| | `-- pylons.css

| |-- templates

| | `-- mytemplate.pt

| |-- tests.py

| `-- views.py

|-- production.ini

|-- README.txt

|-- setup.cfg

`-- setup.py

The MyProject :term:`Project`

The MyProject :term:`project` directory is the distribution and

deployment wrapper for your application. It contains both the myproject

:term:`package` representing your application as well as files used to

describe, run, and test your application.

CHANGES.txtdescribes the changes you've made to the application. It is conventionally written in :term:`ReStructuredText` format.README.txtdescribes the application in general. It is conventionally written in :term:`ReStructuredText` format.development.iniis a :term:`PasteDeploy` configuration file that can be used to execute your application during development.production.iniis a :term:`PasteDeploy` configuration file that can be used to execute your application in a production configuration.setup.cfgis a :term:`setuptools` configuration file used bysetup.py.MANIFEST.inis a :term:`distutils` "manifest" file, naming which files should be included in a source distribution of the package whenpython setup.py sdistis run.setup.pyis the file you'll use to test and distribute your application. It is a standard :term:`setuptools`setup.pyfile.

.. index:: single: PasteDeploy single: ini file

The development.ini file is a :term:`PasteDeploy` configuration file.

Its purpose is to specify an application to run when you invoke pserve,

as well as the deployment settings provided to that application.

The generated development.ini file looks like so:

.. literalinclude:: MyProject/development.ini :language: ini :linenos:

This file contains several sections including [app:main],

[server:main] and several other sections related to logging

configuration.

The [app:main] section represents configuration for your :app:`Pyramid`

application. The use setting is the only setting required to be present

in the [app:main] section. Its default value, egg:MyProject,

indicates that our MyProject project contains the application that should be

served. Other settings added to this section are passed as keyword arguments

to the function named main in our package's __init__.py module. You

can provide startup-time configuration parameters to your application by

adding more settings to this section.

Note

See :ref:`pastedeploy_entry_points` for more information about the

meaning of the use = egg:MyProject value in this section.

The pyramid.reload_templates setting in the [app:main] section is a

:app:`Pyramid` -specific setting which is passed into the framework. If it

exists, and its value is true, :term:`Chameleon` and :term:`Mako`

template changes will not require an application restart to be detected. See

:ref:`reload_templates_section` for more information.

Warning

The pyramid.reload_templates option should be turned off for

production applications, as template rendering is slowed when it is turned

on.

The pyramid.includes setting in the [app:main] section tells Pyramid

to "include" configuration from another package. In this case, the line

pyramid.includes = pyramid_debugtoolbar tells Pyramid to include

configuration from the pyramid_debugtoolbar package. This turns on a

debugging panel in development mode which will be shown on the right hand

side of the screen. Including the debug toolbar will also make it possible

to interactively debug exceptions when an error occurs.

Various other settings may exist in this section having to do with debugging or influencing runtime behavior of a :app:`Pyramid` application. See :ref:`environment_chapter` for more information about these settings.

The name main in [app:main] signifies that this is the default

application run by pserve when it is invoked against this configuration

file. The name main is a convention used by PasteDeploy signifying that

it is the default application.

The [server:main] section of the configuration file configures a WSGI

server which listens on TCP port 6543. It is configured to listen on all

interfaces (0.0.0.0). This means that any remote system which has TCP

access to your system can see your Pyramid application.

The sections that live between the markers # Begin logging configuration

and # End logging configuration represent Python's standard library

:mod:`logging` module configuration for your application. The sections

between these two markers are passed to the logging module's config file

configuration engine when the

pserve or pshell commands are executed. The default

configuration sends application logging output to the standard error output

of your terminal. For more information about logging configuration, see

:ref:`logging_chapter`.

See the :term:`PasteDeploy` documentation for more information about other

types of things you can put into this .ini file, such as other

applications, :term:`middleware` and alternate :term:`WSGI` server

implementations.

.. index:: single: production.ini

The production.ini file is a :term:`PasteDeploy` configuration file with

a purpose much like that of development.ini. However, it disables the

debug toolbar, and filters all log messages except those above the WARN

level. It also turns off template development options such that templates

are not automatically reloaded when changed, and turns off all debugging

options. This file is appropriate to use instead of development.ini when

you put your application into production.

It's important to use production.ini (and not development.ini) to

benchmark your application and put it into production. development.ini

configures your system with a debug toolbar that helps development, but the

inclusion of this toolbar slows down page rendering times by over an order of

magnitude. The debug toolbar is also a potential security risk if you have

it configured incorrectly.

.. index:: single: MANIFEST.in

The MANIFEST.in file is a :term:`distutils` configuration file which

specifies the non-Python files that should be included when a

:term:`distribution` of your Pyramid project is created when you run python

setup.py sdist. Due to the information contained in the default

MANIFEST.in, an sdist of your Pyramid project will include .txt

files, .ini files, .rst files, graphics files, and template files, as

well as .py files. See

http://docs.python.org/distutils/sourcedist.html#the-manifest-in-template for

more information about the syntax and usage of MANIFEST.in.

Without the presence of a MANIFEST.in file or without checking your

source code into a version control repository, setup.py sdist places only

Python source files (files ending with a .py extension) into tarballs

generated by python setup.py sdist. This means, for example, if your

project was not checked into a setuptools-compatible source control system,

and your project directory didn't contain a MANIFEST.in file that told

the sdist machinery to include *.pt files, the

myproject/templates/mytemplate.pt file would not be included in the

generated tarball.

Projects generated by Pyramid scaffolds include a default MANIFEST.in

file. The MANIFEST.in file contains declarations which tell it to

include files like *.pt, *.css and *.js in the generated tarball.

If you include files with extensions other than the files named in the

project's MANIFEST.in and you don't make use of a setuptools-compatible

version control system, you'll need to edit the MANIFEST.in file and

include the statements necessary to include your new files. See

http://docs.python.org/distutils/sourcedist.html#principle for more

information about how to do this.

You can also delete MANIFEST.in from your project and rely on a

setuptools feature which simply causes all files checked into a version

control system to be put into the generated tarball. To allow this to

happen, check all the files that you'd like to be distributed along with your

application's Python files into Subversion. After you do this, when you

rerun setup.py sdist, all files checked into the version control system

will be included in the tarball. If you don't use Subversion, and instead

use a different version control system, you may need to install a setuptools

add-on such as setuptools-git or setuptools-hg for this behavior to

work properly.

.. index:: single: setup.py

The setup.py file is a :term:`setuptools` setup file. It is meant to be

run directly from the command line to perform a variety of functions, such as

testing, packaging, and distributing your application.

Note

setup.py is the de facto standard which Python developers use to

distribute their reusable code. You can read more about setup.py files

and their usage in the Setuptools documentation and The

Hitchhiker's Guide to Packaging.

Our generated setup.py looks like this:

.. literalinclude:: MyProject/setup.py :language: python :linenos:

The setup.py file calls the setuptools setup function, which does

various things depending on the arguments passed to setup.py on the

command line.

Within the arguments to this function call, information about your application is kept. While it's beyond the scope of this documentation to explain everything about setuptools setup files, we'll provide a whirlwind tour of what exists in this file in this section.

Your application's name can be any string; it is specified in the name

field. The version number is specified in the version value. A short

description is provided in the description field. The

long_description is conventionally the content of the README and CHANGES

file appended together. The classifiers field is a list of Trove classifiers

describing your application. author and author_email are text fields

which probably don't need any description. url is a field that should

point at your application project's URL (if any).

packages=find_packages() causes all packages within the project to be

found when packaging the application. include_package_data will include

non-Python files when the application is packaged if those files are checked

into version control. zip_safe indicates that this package is not safe

to use as a zipped egg; instead it will always unpack as a directory, which

is more convenient. install_requires and tests_require indicate that

this package depends on the pyramid package. test_suite points at

the package for our application, which means all tests found in the package

will be run when setup.py test is invoked. We examined entry_points

in our discussion of the development.ini file; this file defines the

main entry point that represents our project's application.

Usually you only need to think about the contents of the setup.py file

when distributing your application to other people, when adding Python

package dependencies, or when versioning your application for your own use.

For fun, you can try this command now:

$ python setup.py sdist

This will create a tarball of your application in a dist subdirectory

named MyProject-0.1.tar.gz. You can send this tarball to other people

who want to install and use your application.

.. index:: single: setup.cfg

The setup.cfg file is a :term:`setuptools` configuration file. It

contains various settings related to testing and internationalization:

Our generated setup.cfg looks like this:

.. literalinclude:: MyProject/setup.cfg :language: guess :linenos:

The values in the default setup file allow various commonly-used internationalization commands and testing commands to work more smoothly.

.. index:: single: package

The myproject :term:`Package`

The myproject :term:`package` lives inside the MyProject

:term:`project`. It contains:

- An

__init__.pyfile signifies that this is a Python :term:`package`. It also contains code that helps users run the application, including amainfunction which is used as a entry point for commands such aspserve,pshell,pviews, and others. - A

templatesdirectory, which contains :term:`Chameleon` (or other types of) templates. - A

tests.pymodule, which contains unit test code for the application. - A

views.pymodule, which contains view code for the application.

These are purely conventions established by the scaffold: :app:`Pyramid` doesn't insist that you name things in any particular way. However, it's generally a good idea to follow Pyramid standards for naming, so that other Pyramid developers can get up to speed quickly on your code when you need help.

.. index:: single: __init__.py

We need a small Python module that configures our application and which

advertises an entry point for use by our :term:`PasteDeploy` .ini file.

This is the file named __init__.py. The presence of an __init__.py

also informs Python that the directory which contains it is a package.

.. literalinclude:: MyProject/myproject/__init__.py :language: python :linenos:

Line 1 imports the :term:`Configurator` class from :mod:`pyramid.config` that we use later.

Lines 4-11 define a function named

mainthat returns a :app:`Pyramid` WSGI application. This function is meant to be called by the :term:`PasteDeploy` framework as a result of runningpserve.Within this function, application configuration is performed.

Line 7 creates an instance of a :term:`Configurator`.

Line 8 registers a static view, which will serve up the files from the

myproject:static:term:`asset specification` (thestaticdirectory of themyprojectpackage).Line 9 adds a :term:`route` to the configuration. This route is later used by a view in the

viewsmodule.Line 10 calls

config.scan(), which picks up view registrations declared elsewhere in the package (in this case, in theviews.pymodule).Line 11 returns a :term:`WSGI` application to the caller of the function (Pyramid's pserve).

.. index:: single: views.py

Much of the heavy lifting in a :app:`Pyramid` application is done by view callables. A :term:`view callable` is the main tool of a :app:`Pyramid` web application developer; it is a bit of code which accepts a :term:`request` and which returns a :term:`response`.

.. literalinclude:: MyProject/myproject/views.py :language: python :linenos:

Lines 4-6 define and register a :term:`view callable` named my_view. The

function named my_view is decorated with a view_config decorator

(which is processed by the config.scan() line in our __init__.py).

The view_config decorator asserts that this view be found when a

:term:`route` named home is matched. In our case, because our

__init__.py maps the route named home to the URL pattern /, this

route will match when a visitor visits the root URL. The view_config

decorator also names a renderer, which in this case is a template that

will be used to render the result of the view callable. This particular view

declaration points at templates/mytemplate.pt, which is a :term:`asset

specification` that specifies the mytemplate.pt file within the

templates directory of the myproject package. The asset

specification could have also been specified as

myproject:templates/mytemplate.pt; the leading package name and colon is

optional. The template file it actually points to is a :term:`Chameleon` ZPT

template file.

This view callable function is handed a single piece of information: the

:term:`request`. The request is an instance of the :term:`WebOb`

Request class representing the browser's request to our server.

This view returns a dictionary. When this view is invoked, a

:term:`renderer` converts the dictionary returned by the view into HTML, and

returns the result as the :term:`response`. This view is configured to

invoke a renderer which uses a :term:`Chameleon` ZPT template

(templates/my_template.pt).

See :ref:`views_which_use_a_renderer` for more information about how views, renderers, and templates relate and cooperate.

Note

Because our development.ini has a pyramid.reload_templates =

true directive indicating that templates should be reloaded when

they change, you won't need to restart the application server to

see changes you make to templates. During development, this is

handy. If this directive had been false (or if the directive

did not exist), you would need to restart the application server

for each template change. For production applications, you should

set your project's pyramid.reload_templates to false to increase

the speed at which templates may be rendered.

.. index:: single: static directory

This directory contains static assets which support the mytemplate.pt

template. It includes CSS and images.

The single :term:`Chameleon` template that exists in the project. Its

contents are too long to show here, but it displays a default page when

rendered. It is referenced by the call to @view_config as the

renderer of the my_view view callable in the views.py file. See

:ref:`views_which_use_a_renderer` for more information about renderers.

Templates are accessed and used by view configurations and sometimes by view functions themselves. See :ref:`templates_used_directly` and :ref:`templates_used_as_renderers`.

.. index:: single: tests.py

The tests.py module includes unit tests for your application.

.. literalinclude:: MyProject/myproject/tests.py :language: python :linenos:

This sample tests.py file has a single unit test defined within it. This

test is executed when you run python setup.py test. You may add more

tests here as you build your application. You are not required to write

tests to use :app:`Pyramid`, this file is simply provided as convenience and

example.

See :ref:`testing_chapter` for more information about writing :app:`Pyramid` unit tests.

.. index:: pair: modifying; package structure

It is best practice for your application's code layout to not stray too much from accepted Pyramid scaffold defaults. If you refrain from changing things very much, other Pyramid coders will be able to more quickly understand your application. However, the code layout choices made for you by a scaffold are in no way magical or required. Despite the choices made for you by any scaffold, you can decide to lay your code out any way you see fit.

For example, the configuration method named

:meth:`~pyramid.config.Configurator.add_view` requires you to pass a

:term:`dotted Python name` or a direct object reference as the class or

function to be used as a view. By default, the starter scaffold would

have you add view functions to the views.py module in your package.

However, you might be more comfortable creating a views directory, and

adding a single file for each view.

If your project package name was myproject and you wanted to arrange all

your views in a Python subpackage within the myproject :term:`package`

named views instead of within a single views.py file, you might:

- Create a

viewsdirectory inside yourmyprojectpackage directory (the same directory which holdsviews.py). - Move the existing

views.pyfile to a file inside the newviewsdirectory named, say,blog.py. - Create a file within the new

viewsdirectory named__init__.py(it can be empty, this just tells Python that theviewsdirectory is a package.

You can then continue to add view callable functions to the blog.py

module, but you can also add other .py files which contain view callable

functions to the views directory. As long as you use the

@view_config directive to register views in conjunction with

config.scan() they will be picked up automatically when the application

is restarted.

It is possible to use the pshell command to load a Python interpreter

prompt with a similar configuration as would be loaded if you were running

your Pyramid application via pserve. This can be a useful debugging tool.

See :ref:`interactive_shell` for more details.

The code generated by an :app:`Pyramid` scaffold assumes that you will be

using the pserve command to start your application while you do

development. pserve is a command that reads a :term:`PasteDeploy`

.ini file (e.g. development.ini) and configures a server to serve a

Pyramid application based on the data in the file.

pserve is by no means the only way to start up and serve a :app:`Pyramid`

application. As we saw in :ref:`firstapp_chapter`, pserve needn't be

invoked at all to run a :app:`Pyramid` application. The use of pserve to

run a :app:`Pyramid` application is purely conventional based on the output

of its scaffolding. But we strongly recommend using while developing your

application, because many other convenience introspection commands (such as

pviews, prequest, proutes and others) are also implemented in

terms of configuration availability of this .ini file format. It also

configures Pyramid logging and provides the --reload switch for

convenient restarting of the server when code changes.

Pyramid scaffolds generate projects which use the :term:`Waitress` WSGI server. Waitress is a server that is suited for development and light production usage. It's not the fastest nor the most featureful WSGI server. Instead, its main feature is that it works on all platforms that Pyramid needs to run on, making it a good choice as a default server from the perspective of Pyramid's developers.

Any WSGI server is capable of running a :app:`Pyramid` application. But we suggest you stick with the default server for development, and that you wait to investigate other server options until you're ready to deploy your application to production. Unless for some reason you need to develop on a non-local system, investigating alternate server options is usually a distraction until you're ready to deploy. But we recommend developing using the default configuration on a local system that you have complete control over; it will provide the best development experience.

One popular production alternative to the default Waitress server is :term:`mod_wsgi`. You can use mod_wsgi to serve your :app:`Pyramid` application using the Apache web server rather than any "pure-Python" server like Waitress. It is fast and featureful. See :ref:`modwsgi_tutorial` for details.

Another good production alternative is :term:`Green Unicorn` (aka

gunicorn). It's faster than Waitress and slightly easier to configure

than mod_wsgi, although it depends, in its default configuration, on having a

buffering HTTP proxy in front of it. It does not, as of this writing, work

on Windows.