ThunderKittens is a framework to make it easy to write fast deep learning kernels in CUDA (and, soon, MPS, and eventually ROCm and others, too!)

ThunderKittens is built around three key principles:

- Simplicity. ThunderKittens is stupidly simple to write.

- Extensibility. ThunderKittens embeds itself natively, so that if you need more than ThunderKittens can offer, it won’t get in your way of building it yourself.

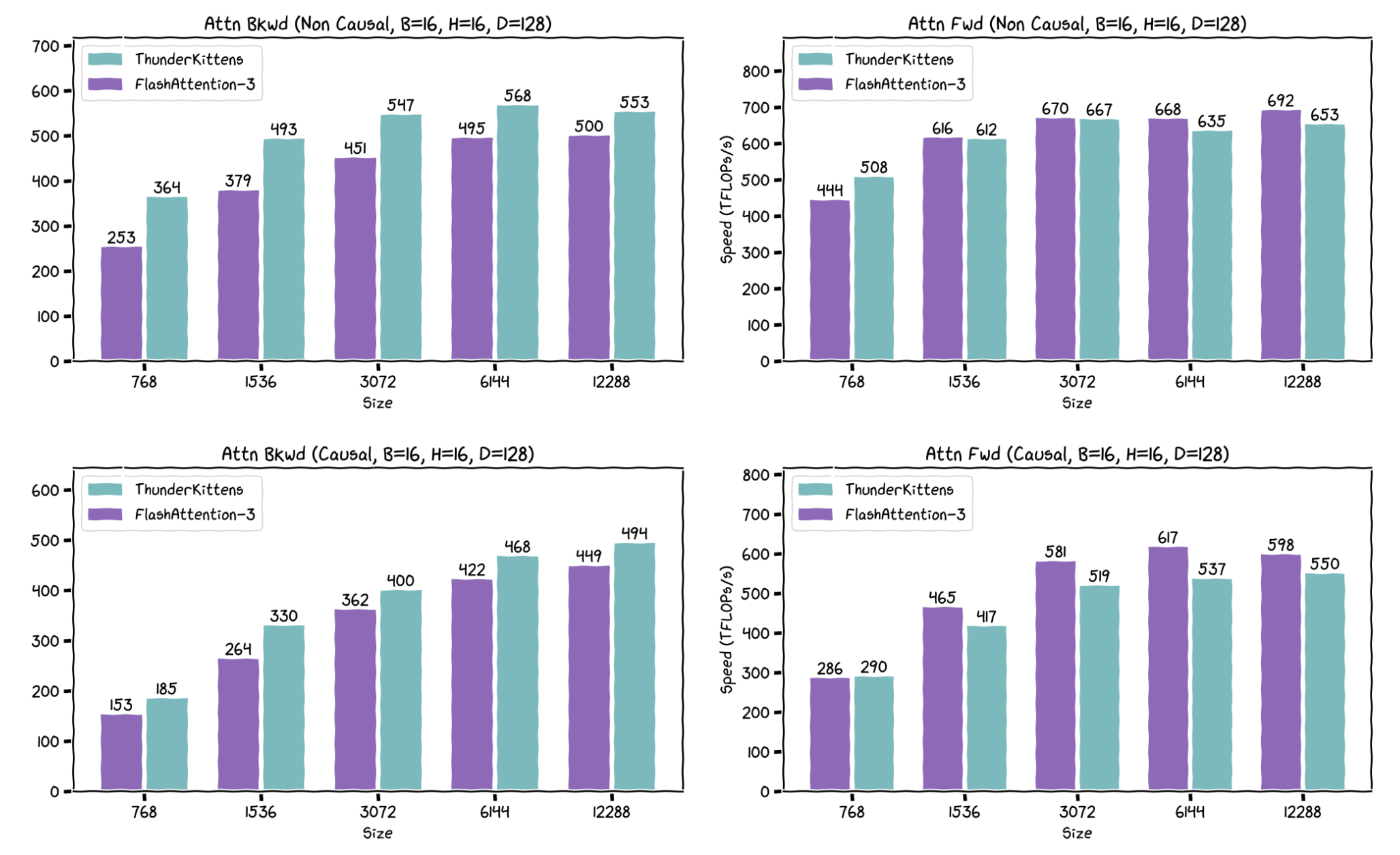

- Speed. Kernels written in ThunderKittens should be at least as fast as those written from scratch -- especially because ThunderKittens can do things the “right” way under the hood. We think our Flash Attention 3 implementation speaks for this point.

ThunderKittens is built from the hardware up -- we do what the silicon tells us. And modern GPUs tell us that they want to work with fairly small tiles of data. A GPU is not really a 1000x1000 matrix multiply machine (even if it is often used as such); it’s a manycore processor where each core can efficiently run ~16x16 matrix multiplies. Consequently, ThunderKittens is built around manipulating tiles of data no smaller than 16x16 values.

ThunderKittens makes a few tricky things easy that enable high utilization on modern hardware.

- Tensor cores. ThunderKittens can call fast tensor core functions, including asynchronous WGMMA calls on H100 GPUs.

- Shared Memory. I got ninety-nine problems but a bank conflict ain’t one.

- Loads and stores. Hide latencies with asynchronous copies and address generation with TMA.

- Distributed Shared Memory. L2 is so last year.

- Worker overlapping. Use our Load-Store-Compute-Finish template to overlap work and I/O.

Example: A Simple Atention Kernel

Here’s an example of what a simple FlashAttention-2 kernel for an RTX 4090 looks like written in ThunderKittens.

#include "kittens.cuh"

using namespace kittens;

constexpr int NUM_WORKERS = 4; // This kernel uses 4 worker warps per block, and 2 blocks per SM.

template<int D> constexpr size_t ROWS = 16*(128/D); // height of each worker tile (rows)

template<int D, typename T=bf16, typename L=row_l> using qkvo_tile = rt<T, ROWS<D>, D, L>;

template<int D, typename T=float> using attn_tile = rt<T, ROWS<D>, ROWS<D>>;

template<int D> using shared_tile = st_bf<ROWS<D>, D>;

template<int D> using global_layout = gl<bf16, -1, -1, -1, D>; // B, H, g.Qg.rows specified at runtime, D=64 known at compile time for this kernel

template<int D> struct globals { global_layout<D> Qg, Kg, Vg, Og; };

template<int D> __launch_bounds__(NUM_WORKERS*WARP_THREADS, 1)

__global__ void attend_ker(const __grid_constant__ globals<D> g) {

using load_group = kittens::group<2>; // pairs of workers collaboratively load k, v tiles

int loadid = load_group::groupid(), workerid = kittens::warpid(); // which worker am I?

constexpr int LOAD_BLOCKS = NUM_WORKERS / load_group::GROUP_WARPS;

const int batch = blockIdx.z, head = blockIdx.y, q_seq = blockIdx.x * NUM_WORKERS + workerid;

extern __shared__ alignment_dummy __shm[]; // this is the CUDA shared memory

shared_allocator al((int*)&__shm[0]);

// K and V live in shared memory. Here, we instantiate three tiles for a 3-stage pipeline.

shared_tile<D> (&k_smem)[LOAD_BLOCKS][3] = al.allocate<shared_tile<D>, LOAD_BLOCKS, 3>();

shared_tile<D> (&v_smem)[LOAD_BLOCKS][3] = al.allocate<shared_tile<D>, LOAD_BLOCKS, 3>();

// We also reuse this memory to improve coalescing of DRAM reads and writes.

shared_tile<D> (&qo_smem)[NUM_WORKERS] = reinterpret_cast<shared_tile<D>(&)[NUM_WORKERS]>(k_smem);

// Initialize all of the register tiles.

qkvo_tile<D, bf16> q_reg, k_reg; // Q and K are both row layout, as we use mma_ABt.

qkvo_tile<D, bf16, col_l> v_reg; // V is column layout, as we use mma_AB.

qkvo_tile<D, float> o_reg; // Output tile.

attn_tile<D, float> att_block; // attention tile, in float. (We want to use float wherever possible.)

attn_tile<D, bf16> att_block_mma; // bf16 attention tile for the second mma_AB. We cast right before that op.

typename attn_tile<D, float>::col_vec max_vec_last, max_vec, norm_vec; // these are column vectors for the in-place softmax.

// each warp loads its own Q tile of 16x64

if (q_seq*ROWS<D> < g.Qg.rows) {

load(qo_smem[workerid], g.Qg, {batch, head, q_seq, 0}); // going through shared memory improves coalescing of dram reads.

__syncwarp();

load(q_reg, qo_smem[workerid]);

}

__syncthreads();

// temperature adjustment. Pre-multiplying by lg2(e), too, so we can use exp2 later.

if constexpr(D == 64) mul(q_reg, q_reg, __float2bfloat16(0.125f * 1.44269504089));

else if constexpr(D == 128) mul(q_reg, q_reg, __float2bfloat16(0.08838834764f * 1.44269504089));

// initialize flash attention L, M, and O registers.

neg_infty(max_vec); // zero registers for the Q chunk

zero(norm_vec);

zero(o_reg);

// launch the load of the first k, v tiles

int kv_blocks = g.Qg.rows / (LOAD_BLOCKS*ROWS<D>), tic = 0;

load_group::load_async(k_smem[loadid][0], g.Kg, {batch, head, loadid, 0});

load_group::load_async(v_smem[loadid][0], g.Vg, {batch, head, loadid, 0});

// iterate over k, v for these q's that have been loaded

for(auto kv_idx = 0; kv_idx < kv_blocks; kv_idx++, tic=(tic+1)%3) {

int next_load_idx = (kv_idx+1)*LOAD_BLOCKS + loadid;

if(next_load_idx*ROWS<D> < g.Kg.rows) {

int next_tic = (tic+1)%3;

load_group::load_async(k_smem[loadid][next_tic], g.Kg, {batch, head, next_load_idx, 0});

load_group::load_async(v_smem[loadid][next_tic], g.Vg, {batch, head, next_load_idx, 0});

load_async_wait<2>(); // next k, v can stay in flight.

}

else load_async_wait(); // all must arrive

__syncthreads(); // Everyone's memory must be ready for the next stage.

// now each warp goes through all of the subtiles, loads them, and then does the flash attention internal alg.

#pragma unroll LOAD_BLOCKS

for(int subtile = 0; subtile < LOAD_BLOCKS && (kv_idx*LOAD_BLOCKS + subtile) < g.Qg.rows; subtile++) {

load(k_reg, k_smem[subtile][tic]); // load k from shared into registers

zero(att_block); // zero 16x16 attention tile

mma_ABt(att_block, q_reg, k_reg, att_block); // [email protected]

copy(max_vec_last, max_vec);

row_max(max_vec, att_block, max_vec); // accumulate onto the max_vec

sub_row(att_block, att_block, max_vec); // subtract max from attention -- now all <=0

exp2(att_block, att_block); // exponentiate the block in-place.

sub(max_vec_last, max_vec_last, max_vec); // subtract new max from old max to find the new normalization.

exp2(max_vec_last, max_vec_last); // exponentiate this vector -- this is what we need to normalize by.

mul(norm_vec, norm_vec, max_vec_last); // and the norm vec is now normalized.

row_sum(norm_vec, att_block, norm_vec); // accumulate the new attention block onto the now-rescaled norm_vec

copy(att_block_mma, att_block); // convert to bf16 for mma_AB

load(v_reg, v_smem[subtile][tic]); // load v from shared into registers.

mul_row(o_reg, o_reg, max_vec_last); // normalize o_reg in advance of mma_AB'ing onto it

mma_AB(o_reg, att_block_mma, v_reg, o_reg); // mfma onto o_reg with the local attention@V matmul.

}

}

div_row(o_reg, o_reg, norm_vec);

__syncthreads();

if (q_seq*ROWS<D> < g.Qg.rows) { // write out o.

store(qo_smem[workerid], o_reg); // going through shared memory improves coalescing of dram writes.

__syncwarp();

store(g.Og, qo_smem[workerid], {batch, head, q_seq, 0});

}

}Altogether, this is about 100 lines of code, and achieves about 155 TFLOPs on an RTX 4090. (93% of theoretical max.) We’ll go through some of these primitives more carefully in the next section, the ThunderKittens manual.

To use Thunderkittens, there's not all that much you need to do with TK itself. It's a header only library, so just clone the repo, and include kittens.cuh. Easy money.

But ThunderKittens does use a bunch of modern stuff, so it has fairly aggressive requirements.

- CUDA 12.3+. Anything after CUDA 12.1 will probably work, but you'll likely end up with serialized wgmma pipelines on H100s due to a bug in those earlier versions of CUDA. We do our dev work on CUDA 12.6, because we want our kittens to play in the nicest, most modern environment possible.

- (Extensive) C++20 use -- TK runs on concepts. If you get weird compilation errors, chances are your gcc is out of date.

sudo apt update

sudo apt install gcc-10 g++-10

sudo update-alternatives --install /usr/bin/gcc gcc /usr/bin/gcc-10 100 --slave /usr/bin/g++ g++ /usr/bin/g++-10

sudo apt update

sudo apt install clang-10If you can't find nvcc, or you experience issues where your environment is pointing to the wrong CUDA version:

export CUDA_HOME=/usr/local/cuda-12.6/

export PATH=${CUDA_HOME}/bin:${PATH}

export LD_LIBRARY_PATH=${CUDA_HOME}/lib64:$LD_LIBRARY_PATHWe've provided a number of TK kernels in the kernels/ folder! To use these with PyTorch bindings:

- Set environment variables.

To compile examples, run source env.src from the root directory before going into the examples directory. (Many of the examples use the $THUNDERKITTENS_ROOT environment variable to orient themselves and find the src directory.

-

Select the kernels you want to build in

configs.pyfile -

Install:

python setup.py installFinally, thanks to Jordan Juravskey for putting together a quick doc on setting up a kittens-compatible conda.

We've included a set of starter demos in the demos/ folder, showing how to use TK kernels for training and LLM inference (Qwens, Llamas, LoLCATS LLMs, etc.)!

We are excited to feature any demos you build, please link PRs! Potential contributions:

- New kernels: attention decoding, parallel scan, training long convolutions

- New features: converting PyTorch to TK code, supporting new hardware (AMD?)

- Anything else that comes to mind!

To validate your install, and run TK's fairly comprehensive unit testing suite, simply run make -j in the tests folder. Be warned: this may nuke your computer for a minute or two while it compiles thousands of kernels.

ThunderKittens is actually a pretty small library, in terms of what it gives you.

- Data types: (Register + shared) * (tiles + vectors), all parameterized by layout, type, and size.

- Operations for manipulating these objects.

Despite its simplicity, there are still a few sharp edges that you might encounter if you don’t know what’s going on under the hood. So, we do recommend giving this manual a good read before sitting down to write a kernel -- it’s not too long, we promise!

To understand ThunderKittens, it will help to begin by reviewing a bit of how NVIDIA’s programming model works, as NVIDIA provides a few different “scopes” to think about when writing parallel code.

- Thread -- this is the level of doing work on an individual bit of data, like a floating point multiplication. A thread has up to 256 32-bit registers it can access every cycle.

- Warp -- 32 threads make a warp. This is the level at which instructions are issued by the hardware. It’s also the base (and default) scope from which ThunderKittens operates; most ThunderKittens programming happens here.

- Warpgroup -- 4 warps make a warpgroup. This is the level from which asynchronous warpgroup matrix multiply-accumulate instructions are issued. (We really wish we could ignore this level, but you unfortunately need it for the H100.) Correspondingly, many matrix multiply and memory operations are supported at the warpgroup level.

- Block -- N warps make a block, which is the level that shares “shared memory” in the CUDA programming model. In ThunderKittens, N is often 8.

- Grid -- M blocks make a grid, where M should be equal to (or slightly less) than a multiple of the number of SMs on the GPU to avoid tail effects. ThunderKittens does not touch the grid scope except through helping initialize TMA descriptors.

“Register” objects exist at the level of warps -- their contents is split amongst the threads of the warp. Register objects include:

- Register tiles, declared as the

kittens::rtstruct insrc/register_tile/rt.cuh. Kittens provides a few useful wrappers -- for example, a 32 row, 16 column, row-layout bfloat16 register tile can be declared askittens::rt_bf<32,16>;-- row-layout is implicit by default. - Register vectors, which are associated with register tiles. They come in three flavors: naive, aligned, and orthogonal. What's going on under the hood is a bit too complicated for a readme, but what you need to know is that the naive layout is used for when you expect to do lots of compute on vectors (like a layernorm), and otherewise you should just instantiate column or row vectors depending on how you want to interact with a tile, and let TK take care of the layout for you. Column vectors are used to reduce or map across tile rows (it's a single column of the tile), and row vectors reduce and map across tile columns (a single row of the tile). For example, to hold the sum of the rows of the tile declared above, we would create a

kittens::rt_bf<32,16>::col_vec;In contrast, “Shared” objects exist at the level of the block, and sit only in shared memory.

All ThunderKittens functions follow a common signature. Much like an assembly language (ThunderKittens' origin comes from thinking about an idealized tile-oriented RISC instruction set), the destination of every function is the first operand, and the source operands are passed sequentially afterwards.

For example, if we have three 32 row, 64 col floating point register tiles: kittens::rt_fl<32,64> a, b, c;, we can element-wise multiply a and b and store the result in c with the following call: kittens::mul(c, a, b);.

Similarly, if we want to then store the result into a half-precision shared tile __shared__ kittens:st_hf<32, 64> s;, we write the function analogously: kittens::store(s, c);.

ThunderKittens tries hard to protect you from yourself. In particular, ThunderKittens wants to know layouts of objects at compile-time and will make sure they’re compatible before letting you do operations. This is important because there are subtleties to the allowable layouts for certain operations, and without static checks it is very easy to get painful silent failures. For example, a normal matrix multiply requires the B operand to be in a column layout, whereas an outer dot product requires the B operand to be in a row layout.

If you are being told an operation that you think exists doesn't exist, double-check your layouts -- this is the most common error. Only then report a bug :)

By default, ThunderKittens operations exist at the warp-level. In other words, each function expects to be called by only a single warp, and that single warp will do all of the work of the function. If multiple warps are assigned to the same work, undefined behavior will result. (And if the operation involves memory movement, it is likely to be completely catastrophic.) In general, you should expect your programming pattern to involve instantiating a warpid at the beginning of the kernel with kittens::warpid(), and assigning tasks to data based on that id.

However, not all ThunderKittens functions operate at the warp level. Many important operations, particularly WGMMA instructions, require collaborative groups of warps. These operations exist in the templated kittens::group<collaborative size>. For example, wgmma instructions are available through kittens::group<4>::mma_AB (or kittens::warpgroup::mma_AB, which is an alias.) Groups of warps can also collaboratively load shared memory or do reductions in shared memory

Most operations in ThunderKittens are pure functional. However, some operations do have special restrictions; ThunderKittens tries to warn you by giving them names that stand out. For example, a register tile transpose needs separable arguments: if it is given the same underlying registers as both source and destination, it will silently fail. Consequently, it is named transpose_sep.

Learn more about ThunderKittens and how GPUs work by checking out: