At this point we're going to talk about best practices for develop Restful API

- Introduction to REST

- URL construction

- Operations over resources

- Status codes

- Payload formatting

- Filters

- Pagination

- HATEOAS

- API Versioning

- API throughput restrictions

- OAuth

- Errors

- Status and Health endpoints

- References

In this guide we are going to describe the best practices we consider most relevant at design time for a good REST API.

According with the wikipedia definition:

- Representational State Transfer (REST) is the software architectural style of the World Wide Web. REST gives a coordinated set of constraints to the design of components in a distributed hypermedia system that can lead to a higher-performing and more maintainable architecture. [1]

In the above definition, we can see that REST is a architectural style not an implementation. An implementation of this architecture is RESTFul. This is a common mistake that some people have.

The use of REST is often preferred over the more heavyweight SOAP (Simple Object Access Protocol) style because REST does not leverage as much bandwidth, which makes it a better fit for use over the Internet.

REST, which typically runs over HTTP (Hypertext Transfer Protocol), has several architectural constraints:

-

Decouples consumers from producers

-

Stateless existence

-

Able to leverage a cache

-

Leverages a layered system

-

Leverages a uniform interface

The REST style emphasizes that interactions between clients and services is enhanced by having a limited number of operations (verbs). Flexibility is provided by assigning resources (nouns) their own unique Universal Resource Identifiers (URIs). Because each verb has a specific meaning (GET, POST, PUT and DELETE), REST avoids ambiguity.

The use of hypermedia both for application information as to the state transitions of the application: the representation of this state in a REST system are typically HTML, XML or JSON. As a result, it is possible to browse a resource REST to many others simply following links without requiring the use of registries or another additional infrastructure.

The first important thing in the URL construction is not using verbs, only nouns. This is because the verbs are implicit in the method:

| Method | Verb |

|---|---|

| POST | Create |

| GET | Read |

| PUT | Update |

| DELETE | Delete |

With this in mind, you can start thinking which are the best nouns that describe your resources. It is good that the names are as simple as posible and best describe the resource.

There are some points to consider when you construct the URL:

- Shorts, to makes them easy to write and remenber.

- Predictable, to makes the users understand them and the site structure.

- The nouns must be in plural to make more easy to use for the users.

- Use the same noun with the differents methods of http to do the actions that represent the methods.

###Relations

If there is a relation that can only exist within another resource. You must to put the reference of the resources one next to the other.

/films/57/reviews // Return all the reviews of the film 57

/films/57/reviews/5 // Return the review 5 of the film 57

###Versioning It is advisable to put the version of the API in the URL and don't release without it. Another recommendation is that the version number is preceded by a v to avoid disambiguations.

Only put the MAJOR version number, never the MINOR or PATCH. For example don't use v1.2 or v2.1.3.

Correct form:

/api/v1/films // Return all the films of version 1

/api/v2/films/57 // Return the film 57 of version 2

The operations over resources are limited, the variety is on the resources. The operations over REST are specified as the standard HTTP methods, it constraints the construction of operations trough these methods.

There are operations that are idempotent, it means that it can be called many times without different outcomes. It would not matter if the method is called only once, or ten times over, the system state will be the same.

Moreover, there are safe operations, which should never change the resource. These operations could be cached without any consequence to the resource.

In a REST implementation there are four basic operations which can be published for a resource.

This operation retrieves all the information of a resource, or all resources in a collection (if the resource is a collection). It's a safe operation and it should not have other effect.

GET /clients/123

It introduces an item in the collection represented by the resource. It is used to create a new item in the collection, the URI of the final resource will be defined by the server.

POST /products

{ "name": "car", "color": "black" }

PUT operation requests that the entity is stored in the resource indicated. It means that the resource doesn't exist, it creates it. However, if the resource exists, it is overwritten by the given entity. Because of this behavoir, it is idempotent.

POST and PUT are similar, POST will be used when we don't know the locality of the resource, and PUT where we know it. For this reason, POST is usually implemented as create operation while PUT can be used as update.

PUT /products/123

{ "name": "car", "color": "black" }

It deletes the specified resource. Despite the server could return other response if the item already was deleted (the resource does not exist), this operation is idempotent, because the system status will be the same.

DELETE /client/123

These are the basic operations, they allow to implement CRUD operations, but there are some extra operations. It can be used in some special requirements.

HEAD operation is similar to GET, with the difference that with HEAD operation the data retrieved only includes the header. Normally it is used if the size of content of the resources is large.

All the operations doesn't have to be implemented, with OPTIONS operation the client can discover the list of methods implemented for a resource.

The HTTP methods PATCH can be used to update partial resources. While PUT operation must take a full resource representation as the request entity (if only few attributes are provided, the others should be removed), PATCH operation allow partial changes to a resource. It is not idempotent. This operation should not be used as a partial data which only will be updated, it should define the 'suboperation' that are going to do over the resource.

PATCH /clients/123

[

{ "op": "replace", "path": "/name", "value": "Patricia" }

]

All these operations, specially the basic operations must be used like they were defined. POST operation must never be used to get a resource, or GET to produce any modification. All implementations in REST should be defined as a combination of resource-request_method, don't use new operations, respect standard HTTP methods.

When you are developing a REST API, a common doubt is what status code use in response.

One of the most important point, while you are designing an API Rest, is correctly choose how we will inform our customers of the status of their requests. Since one of the main features of the REST services is that they are built on HTTP protocol, the best way to inform the user will be to use HTTP status codes.

It is a good practice to add to the response of REST services a new field "result" which contains HTTP status code number and a more descriptive message related to contexts of the request.

When you are creating new resources, you have to report to client that these resources has been created.

Method: POST (We can also use PUT method intead of POST, but POST it's most recomended for creating resources).

| Result | Code | Response Body |

|---|---|---|

| Sucessful created | 201 | Empty |

| Bad Request | 400 | codeError and description |

| Invalid credentials | 401 | codeError and description |

When you are updating existing resources, you have to report to client that these resources has been updated.

Method: PUT (We can also use POST method intead of PUT, but PUT it's most recomended for updating resources).

| Result | Code | Response Body |

|---|---|---|

| Sucessful updated | 200 | Empty or fields of updated resource |

| Bad Request | 400 | codeError and description recommended |

| Invalid credentials | 401 | codeError and description recommended |

| Resource not found | 404 | Empty |

When you are querying an unique and existing resource, you have to report to client the content of this resource.

Method: GET.

| Result | Code | Response Body |

|---|---|---|

| Resource founded | 200 | Resource with partially or fully data |

| Resource don't exists | 204 | Empty |

| Bad Request | 400 | codeError and description recommended |

| Invalid credentials | 401 | codeError and description recommended |

| Resource not found | 404 | Empty |

When you are querying a list of resources by certain pattern, you have to report to client at least a list with some info about these resources.

It's also recommended to return info about pagination like total number of resources in list, number of pages, current page, etc....

Method: GET.

| Result | Code | Response Body |

|---|---|---|

| Resources founded | 200 | Resource list with partial or full data |

| Resources not founded | 204 | Empty |

| Resources paginated | 206 | Resource list with pagination info |

| Bad Request | 400 | codeError and description recommended |

| Invalid credentials | 401 | codeError and description recommended |

There are other status codes than have to be taken into account:

| Action | Code | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Request to non-existent or without sense method | 405 | PUT over all resource collection |

| Request to existent resource with invalid headers | 412 | One header is no correct or field missed |

These status codes are informative and tell the user that his request has been processed correctly.

| Code | Message | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 200 | OK | Request completed successfully. Used mainly in response to GET methods |

| 201 | Created | New resource has been created. Used in response to POST methods |

| 202 | Accepted | Request has been accepted but has not been completed yet. It is a response code which is commonly used for asynchronous processing |

| 204 | No Content | Request has been completed successfully but the method does not return any information. For example, when a resource exists but it does not have information or in response to a DELETE request |

| 206 | Partial Content | Partial response indicates that there are more elements available to return. It is good practice to use the Content-Range header to indicate at what position we are in and how many elements is able to return the service |

These response codes indicate to the user to do any additional actions to complete his request

| Code | Message | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 301 | Moved Permanently | The requested resource has been assigned a new permanent URI and any future references to this resource should use one of the returned URIs. |

| 304 | Not Modified | In HEAD and GET requests indicates that the requested resource has not changed since the last request received. Mostly used in caching systems |

These response codes are used to tell the client that there are some type of error in his request and he have to fix it before send another request

| Code | Message | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 400 | Bad Request | The request could not be understood by the server due to malformed syntax. For example, request parameters in bad format in the case of a GET method or a field of a json that does not validate properly in the case of PUT/POSTS methods |

| 401 | Unauthorized | The request requires user authentication |

| 403 | Forbidden | The requested action cannot be carried out on the specified resource. For example, a DELETE operation on a resource that cannot be deleted |

| 404 | Not Found | You cannot perform any operation on the requested resource because server has not found anything matching the Request-URI |

| 405 | Method Now Allowed | Unable to perform the specified action on the requested resource |

| 409 | Conflict | The request cannot be completed because there is a problem with the current state of the resource |

| 410 | Gone | The resource in this endpoint is no longer available. Useful for deprecate older versions of an API |

| 429 | Too Many Request | Request has been denied because exceeded of rate limits |

They are used to inform the user of errors in valid requests

| Code | Message | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 500 | Internal Server Error | Generic code indicating an unexpected error |

| 503 | Service Unavailable | The server is currently unable to handle the request due to a temporary overloading or maintenance of the server |

The payload is the actual data provided in a REST message, the payload does not include the overhead data. That means it is not either the headers or the envelope.

Both the requests and the responses can have a payload.

For example, in operations such as GET and DELETE, it does not make sense, because there should not be content in the payload. On the other hand, operations like PUT or POST usually contains a payload with data. Most of the responses may contain a payload, for responses with data content and for providing extra information about the success (or not) of the operation.

There are many formats as payload, the most used are JSON and XML though. The structure for a payload depends on the information that is represented on it. It will not be the same for an item creation, error content response, successful message, etc.

Respecting status codes - It's a bad practice to send a response with status 200, and return in the payload the detail that the response was not successful, with a particular messages result format for our API. The status code for a response must be used to define how was it, don't use the payload to specify the nature of the response. The payload should be used in that case to specify the detail of the operation result.

Sometimes, our API can be prepared to return the responses in xml or json format, the client should specify the format required. There are two ways to define the format of the response expected:

- Accept header: Indicating in the Accept http header what are the contents types accepted. The request put application/xml or application/json to ask for a xml or json response format.

- Extension: other way to specify the response format is indicating the extension on the resource. For example, GET /api/resource.xml?param=value or /api/resource.json?param=value.

When we are developing a new project, it's important to define a common layout for payloads on requests and responses. It will make easier for us and the clients of our REST api. It facilitates to identify any kind of response, error or success, if the layout doesn't match, it could produce confusion and errors.

There are several ways to filter the resources of a REST Api. However is a good practice to design an API with the next four features

Avoid use one unique parameter for filtering all fields, is a much better approach to use one parameter for each field to filter. Use multiple values separted by comma if you need to filter a resource by multiple field values.

GET /campaigns?status=computed&provider=CVIP,BBVAGeneric parameter "sort" can be used to describe sorting rules. Allow sort by multiple fields with the use of a list of fields separated by comma. Use - sign before fields to sort in descent order and no sign to sort in ascending order.

GET /campaigns?sort=last_update,-statusSometimes API consumers don't need all attributes of a resource. Is a good practice give the consumer the ability to choose returned fields. This will improve API's performance and reduce the network bandwidth.

GET /campaigns?fields=id,status,nameDefine search as a sub-resorce for your collection. Use generic query parameter like "q" to perform a full text search over your resources and return the search result in the same format as a normal list result. In order to make more complex searches allow the use of full text search operators like + - or "/ .

GET /campaigns/search?q=PAYPAL-BBVAThe right way to include pagination details today is using the Link header introduced by RFC 5988

An API that uses the Link header can return a set of ready-made links so the API consumer doesn't have to construct links themselves.

Link: <https://www.beeva.com/sample/api/v1/cars?offset=15&limit=5>; rel="next",

<https://www.beeva.com/sample/api/v1/cars?offset=50&limit=3>; rel="last",

<https://www.beeva.com/sample/api/v1/cars?offset=0&limit=5>; rel="first",

<https://www.beeva.com/sample/api/v1/cars?offset=5&limit=5>; rel="prev"| Name | Description |

|---|---|

| next | The link relation for the immediate next page of results. |

| last | The link relation for the last page of results. |

| first | The link relation for the first page of results. |

| prev | The link relation for the immediate previous page of results. |

But this isn't a complete solution as many APIs do like to return the additional pagination information, like a count of the total number of available results. An API that requires sending a count can use a custom HTTP header like X-Total-Count.

On the other hand, in order to indicate the page that we want to visualize and amount of data per page, we should use some parameters in the rest calling. There are some kind of pagination-based (you cand find some of them here), and these parameters had been define by pagination-type based.

Anyway whatever pagination-based you choose, there must always be a parameter that indicates the number of individual objects that are returned in each page (usaully is limit) and another one that indicates current page (like page , page_number, offset...)

Sometimes, at Beeva projects, we use a link node in the responses instead of use the link header to paginate. See the example below:

{

"result": {

"code": 206,

"info": "Partial Content"

},

"paging": {

"page_size": 3,

"links": {

"first": {

"href": "https://www.beeva.com/sample/api/v1/cars?offset=0&limit=5"

},

"prev": {

"href": "https://www.beeva.com/sample/api/v1/cars?offset=5&limit=5"

},

"next": {

"href": "https://www.beeva.com/sample/api/v1/cars?offset=15&limit=5"

},

"last": {

"href": "https://www.beeva.com/sample/api/v1/cars?offset=50&limit=3"

}

}

},

"data": [

{

"date": "201401",

"avg": 46.38

},

{

"date": "201402",

"avg": 45.66

},

{

"date": "201403",

"avg": 48.6

}

]

}Definition from Wikipedia: "HATEOAS, an abbreviation for Hypermedia as the Engine of Application State, is a constraint of the REST application architecture that distinguishes it from most other network application architectures. The principle is that a client interacts with a network application entirely through hypermedia provided dynamically by application servers. A REST client needs no prior knowledge about how to interact with any particular application or server beyond a generic understanding of hypermedia. By contrast, in some service-oriented architectures (SOA), clients and servers interact through a fixed interface shared through documentation or an interface description language (IDL). The HATEOAS constraint decouples client and server in a way that allows the server functionality to evolve independently."

Let’s take as an example an Amazon customer who wishes to read the details of his last order. To do this, he has to follow two steps:

- List all his orders

- Select his last order

On the Amazon website, he does not need to be a web expert to read his last order: he just has to login into his account, then click on the “my orders” link and finally select the most recent one.

Now let’s imagine the customer wishes to use an API to do the same thing!

He must begin by reading Amazon documentation to find the URL that returns the list of orders. When he finds it, he must make an actual HTTP call to this URL. He’ll see the reference of his order in the list, but he’ll need to make a second call to another URL to get its details. He will have to figure out how to construct the proper URL from Amazon‘s documentation.

There is one main difference between these two scenarii: In the first one, the customer just needed to know the first URL “http://www.amazon.com” then follow the links on the web page. Whereas in the second one, he needed to read the documentation so as to elaborate the URL.

The drawbacks of the second process are:

- The developers do not like documentation.

- In real life, the documentation is usually not up to date. The developer may miss one or several available services just because they are not properly documented.

- The API is less accessible.

Now let’s assume we develop a component to automatically create these contextual URLs. What happens when Amazon modifies its URLs?

In practical, HATEOAS is like a urban legend. Everybody talks about it but nobody ever witnessed an actual implementation. Paypal proposes one:

[{

"href": "https://api.sandbox.paypal.com/v1/payments/payment/PAY-6RV70583SB702805EKEYSZ6Y",

"rel": "self",

"method": "GET"

}, {

"href": "https://www.sandbox.paypal.com/webscr?cmd=_express-checkout&token=EC-60U79048BN77196",

"rel": "approval_url",

"method": "REDIRECT"

}, {

"href": "https://api.sandbox.paypal.com/v1/payments/payment/PAY-6RV70583SB702805EKEYSZ6Y/execute",

"rel": "execute",

"method": "POST"

}]In our Amazon case, a call to /customers/007 would then return the details of the customer, along with pointers towards linked resources :

GET /customers/007

200 Ok

{

"id": "007",

"firstname": "James",

...,

"links": [{

"rel": "self",

"href": "https://api.domain.com/v1/customers/007",

"method": "GET"

}, {

"rel": "addresses",

"href": "https://api.domain.com/v1/addresses/42",

"method": "GET"

}, {

"rel": "orders",

"href": "https://api.domain.com/v1/orders/1234",

"method": "GET"

},

...

]

}

For implementing HATEOAS, we therefore recomment using the following method, also applied in the pagination section, compliant with RFC 5988 and usable by clients that don’t support several Header “Link”:

GET /customers/007

200 Ok

{

"id":"007",

"firstname":"James",

...

}

Link : https://api.domain.com/v1/customers/007; rel="self"; method:"GET",

https://api.domain.com/v1/addresses/42; rel="addresses"; method:"GET",

https://api.domain.com/v1/orders/1234; rel="orders"; method:"GET"

Make the API Version mandatory and do not release an unversioned API. There are two versioning topics on wich we will talk. The first one is the what versioning specification should we use to release our api. And the second one is how and when should we engage it with our API releasing.

As a especification of our APIs we use Semantic Versioning. This is an spefication authored by Tom Preston-Werner based on three digits MAJOR.MINOR.PATCH

Theses are the main rules about this speficiation

-

A normal version number MUST take the form X.Y.Z where X, Y, and Z are non-negative integers, and MUST NOT contain leading zeroes. X is the major version, Y is the minor version, and Z is the patch version. Each element MUST increase numerically. For instance: 1.9.0 -> 1.10.0 -> 1.11.0.

-

Major version zero (0.y.z) is for initial development. Anything may change at any time. The public API should not be considered stable.

-

Version 1.0.0 defines the public API. The way in which the version number is incremented after this release is dependent on this public API and how it changes.

-

Patch version Z (x.y.Z | x > 0) MUST be incremented if only backwards compatible bug fixes are introduced. A bug fix is defined as an internal change that fixes incorrect behavior.

-

Minor version Y (x.Y.z | x > 0) MUST be incremented if new, backwards compatible functionality is introduced to the public API. It MUST be incremented if any public API functionality is marked as deprecated. It MAY be incremented if substantial new functionality or improvements are introduced within the private code. It MAY include patch level changes. Patch version MUST be reset to 0 when minor version is incremented.

-

Major version X (X.y.z | X > 0) MUST be incremented if any backwards incompatible changes are introduced to the public API. It MAY include minor and patch level changes. Patch and minor version MUST be reset to 0 when major version is incremented.

For performance reasons and to ensure a homogeneous response times APIs, it is good practice to limit the consumption of APIs. This limitation can be performed based on many factors:

- Limit requests in a time slot for an authenticated user. Such limitations are usually carried out in public APIs to control abusive access to the APIs. There are several approaches such as restricting the number of day / month requests for authenticated users.

- Limit requests for public / private consumption API depending on the authenticated user profile. Usually public APIs have limited consumption, always with the concept of ensuring homogeneous consumption of all users allowing resizes infrastructure in stages. Now another factor to consider, the payment appears APIs. If someone pays for higher demand requests, we can not make this service affects the service consumer of APIs, so normally corresponding changes will be made in infrastructure to ensure the number of requests the client demands, and there is a unique routing requests asigned to the user profile.

To manage the rate of requests are often used the following headers in responses of each request:

- X-Rate-Limit-Limit: The number of allowed requests in the current period

- X-Rate-Limit-Remaining: The number of remaining requests in the current period

- X-Rate-Limit-Reset: The number of seconds left in the current period. It is necessary to clarify at this point that should not be confused with a timestamp, you should be the seconds remaining to avoid problems with time zones.

As we can see in the following link, There are multiple APIs that use these headers (and sometimes more), to inform the user of the limits.

For ending this section, when the request limit is reached, the response will return this code status: HTTP - 429 Too Many Requests as indicated in the RFC 6585 Section 4

The OAuth authorization framework enables a third-party application to obtain limited access to an HTTP service, either on behalf of a resource owner by orchestrating an approval interaction between the resource owner and the HTTP service, or by allowing the third-party application to obtain access on its own behalf.

This is a very brief introduction, please refer to OAuth RFC 6749 for a detailed documentation.

It is very important to know the involved roles for the sake of this section understanding:

OAuth defines four roles:

- resource owner : An entity capable of granting access to a protected resource. When the resource owner is a person, it is referred to as an end-user.

- resource server : The server hosting the protected resources, capable of accepting and responding to protected resource requests using access tokens.

- client : An application making protected resource requests on behalf of the resource owner and with its authorization. The term "client" does not imply any particular implementation characteristics (e.g., whether the application executes on a server, a desktop, or other devices).

- authorization server : The server issuing access tokens to the client after successfully authenticating the resource owner and obtaining authorization. The authorization server may be the same server as the resource server or a separate entity. A single authorization server may issue access tokens accepted by multiple resource servers.

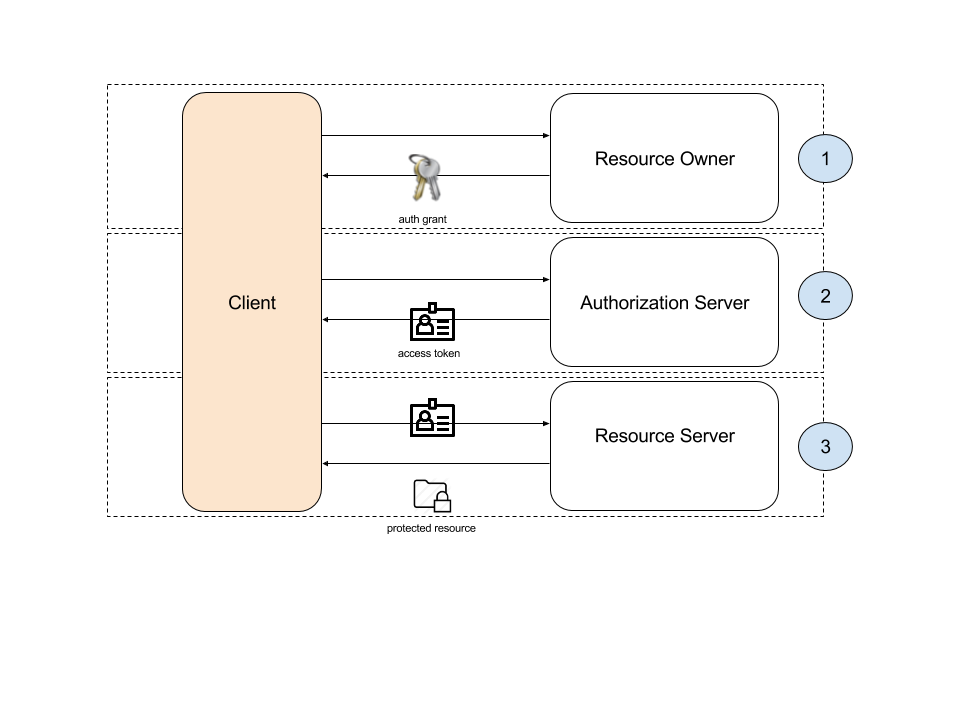

The image below describes the authentication flow (usually referred as OAuth handshake or negotiation).

We can observe 3 separated blocks in this negotiation:

- Authorization request to access protected resources from a resource owner, there are several granting types to use, see references for further details

We recommend to delegate this authorization process to an authorization server, but it could be handled directly by the resource owner

- Access token request, using the authorization grant obtained in the previous step the client obtains a valid OAuth access token

- Retrieval of protected resources, using OAuth access token obtained in previous step

This scenario can be referred as 3-legged OAuth. There is a special case when resource owner and client is the same entity, this is called 2-legged OAuth because there is no need of authorization request from resource owner.

Access tokens are associated to a set of scopes that represent permissions on how and which resources are available for a given token. We recommend to carefully define a rich set of scopes that enable a fine grained set of permissions to restrict client's access and operations to protected resources.

Access tokens should have an expiration time defined. It is not a good practice to allow a token to last forever. If a client need to extend the expiration time, a "refresh token" endpoint should be available. In this case, in step 2 of protocol flow a refresh token is provided along with the access token. This refresh token should be used by the client for refreshing the expiration time of a token. See RFC for further details.

A good practice to avoid an unnecesary traffic overhead to the authorization server is to enable caching in clients. This access token will not change until expires.

Client credentials should never travel as plain text without using SSL on requests. This way credentials are protected from eavesdropping and man-in-the-middle attacks.

However, even with the use of TLS/SSL credentials could be sent to the wrong server using OAuth 2.0 - either by misconfiguration or because the server has been compromised. If this is critical for us, maybe the credentials should not travel as plain text, but signed. This sacrifices complexity over protocol requests for a higher security.

Below is a list of sample implementations of OAuth 2.0:

A major element of web services is planning for when things go wrong, and propagating error messages back to client applications. However, REST-based web services do not have a well-defined convention for returning error messages.

Nonetheless, here are the most important criteria for manage REST API response errors:

-

Error Messages must be readable for humans: Part of the major appeal of REST based web services is that you can open any browser, type in the right URL, and see an immediate response -- no special tools needed. However, HTTP error codes do not always provide enough information and we need to share with client a short description of the error committed.

-

Application Specific Errors: The response body in errors must have the imprint of the application.

-

Error Codes must be readable for other applications: As a third criteria, error codes should be easily readable by other applications.

So the best option for response error are:

-

Use HTTP Status Codes for problems specifically related to HTTP, and not specifically related to your web service.

-

When an error occurs, always return an error code and description document detailing this.

-

Error document must contain both an error code, and a human readable error message.

User error. This can mean that a required field or parameter has not been provided, the value supplied is invalid, or the combination of provided fields is invalid.

This error can be thrown when trying to add a duplicate parent to a Drive item. It can also be thrown when trying to add a parent that would create a cycle in the directory graph.

{

"error": {

"errors": [

{

"domain": "global",

"reason": "badRequest",

"message": "Bad Request"

}],

"code": 400,

"message": "Bad Request"

}

}or

{

"error": "short_description",

"error_description": "longer description, human-readable",

"error_uri": "URI to a detailed error description on the API developer website"

}Invalid authorization header. The access token you're using is either expired or invalid.

{

"error": {

"errors": [

{

"domain": "global",

"reason": "authError",

"message": "Invalid Credentials",

"locationType": "header",

"location": "Authorization",

}],

"code": 401,

"message": "Invalid Credentials"

}

}or

{

"error": "no_credentials",

"error_description": "This resource requires authorization, you must be authenticated and have the correct rights to access it"

}You are identified, but you do not have the necessary authorizations.

{

"error": {

"errors": [

{

"domain": "global",

"reason": "authError",

"message": "Forbidden",

"location": "Authorization",

}],

"code": 403,

"message": "Forbidden"

}

}or

{

"error": "not_allowed",

"error_description": "You're not allowed to perform this request"

}A good practice for you REST API is to reserve a couple of endpoints for checking the status and health/integrity of the API.

The status endpoint allows third party applications to check if your API is UP or DOWN.

A good endpoint could be /status.

The convention for this endpoint is to return a 200 status code response with a very simple response. For example:

{

"status":"UP"

}Any other response status should be interpreted as an outline API.

The health endpoint goes a step further and it does not only informs about the availability of the API but also about its integrity and health.

A good endpoint could be /health.

The response in case that our API is healthy could be very similar to the one returned by the status endpoint, a 200 response with the following body:

{

"health" : "OK"

}We should check the status of every needed sub-component for our API to work correctly. For example, we could check the status of any databases or external services.

In case we need a more verbose response, we could enable a second endpoint whose response could be more detailed. For example, /health/systems could return a 200 response with the following body:

{

"health" : {

"subsystem A" : "OK",

"subsystem B" : "KO",

"subsystem C" : "OK",

"subsystem D" : "OK"

}

}This endpoint should not be published to third party applications because this information is typically needed for internal development or architecture issues.

- [1] REST Wikipedia

- [2] OAuth RFC 6749 OAuth RFC 6749 defined by IETF

- [3] RFC 6585 Section 4: HTTP - 429 Too Many Requests

- [4] Examples API Throughput Restrictions

- [5] Google APIs

- [6] Twitter APIs

BEEVA | 2016