- Preface

- General

- Controllers

- Directives

- Filters

- Services

- Other stuff

- [Testing] (#testing)

- Miscellaneous

Thank you for reading this guide, on how to get the best possible outcomes out of your astonishing Angular app. This guide contains procedures and advices, collected from our experience on the tool over time. Every single item should have not only the what, but also the why using such specific method shall give you better results.

This guide covers development techniques tightly related to Angular JS. Even if them rules could be abstracted into many other tools, you shall see the specific guide for such tool for further best practises.

The content of this guide lays on top of Frontend's best practises, whose contents should be taken into account too when developing an Angular application.

In order to fully understand the practises defined here, it would be really useful to have certain knowledge about how Angular deals with things. So here you'll find brief details on Angular's phases.

During app startup, Angular first calls to its declared config procedures. On these tasks your application should configure all stuff required to initialise your app. Amongst other thigs, this phase usually contains:

- Route configuration.

- i18n configuration.

- Global

$http,$location, and other provider's configurations. - Your custom config.

The run process is another configuration phase. But this time around your app will be fully prepared and actually running. This could be a good place to load your transversal resources, configure app's language, ...

Whilst the run process is engaged once the app is configured (and all stuff will be loaded and ready), during the config phase the application is still loading, and hence Angular hasn't inject your dependencies in order for you to use them. Therefore, during the config phase you will have available this:

| Dependency type | Availability |

|---|---|

| constants | Constants are available throughout all cycles of Angular's life. |

| providers | Angular providers are singletons (just as any other services) that are not yet initialised during config. However, providers provides you (LOL) with a direct access to the declared function before init. |

When you request Angular to load a route, you're internally triggering some tasks to verify and load your route, and several events will be fired.

$routeChangeStart: This event is fired once a new route is requested. If you listen to this event you could intercept all route changes, and make some controlling within (verify authorization for the requested path, log information...).$stateChangeSuccess: Once your new route is loaded and if everything went smooth, you'll get this event triggered.$routeChangeError: If anything went south this event will be dispatched.

NOTE: All above-menctioned events are documented here.

Once this flow finishes, and if everything went ok, your new route will be loaded. Usually routing processes are followed up by rendering processes.

Rendering is the phase in which Angular takes your views and templates and $compiles them. During this lap, all your directives will be engaged, your bindings linked and synced, and your application freed to the user to interact with it. This is all achieved via the $digest cycle.

This rendering flow is in most cases completely automatic. Thanks to Angular's dirty checking, once something changes within your binded model, Angular will internally launch a $digest cycle, in which all targeted values will be checked and updated, and your view should immediately reflect your model updates. There are some cases though in which Angular does not now something has changed, and you need to notify its core to perform a new $digest. This is achieved via the $apply method.

NOTE: As word of advice, read carefully the section about bindings and expressions. Is not usually a good practise to override Angular's native cycle through manual $apply calls, and most of the times this could be overcome with a slightly different approach.

When you inject some dependencies into yours, Angular recognises what you're intending to do by the name of your dependency. Once obfuscation process is through, your variable names would be messed up, and hence Angular would not have a clue about what to inject where.

Angular's solution is to explicitely define dependencies into an array, before declaring your dependency function. In fact, your dependency function will be the last item of such array, and it will receive as arguments all other earlier items.

/*

* Do this

*/

angular.module('myFancyApp')

.controller('myFancyCtrl', ['$scope', '$filter', 'otherDependency', function($scope, $filter, otherDependency) {

...

}]);

/*

* InsteadOf this

*/

angular.module('myFancyApp')

.controller('myFancyCtrl', function($scope, $filter, otherDependency) {

...

});NOTE: On some examples below we have ommited this syntax. Our only purpose is to keep this guide short.

As in any other development language/tool/technique, atomicity gives you great leverage on reading/understanding/refactoring your code. If you don't avoid having thousands lines files with many dependencies within them, using your code will eventually be a nightmare.

/*

* Do this

*/

// SampleDirective.js

angular.module('myFancyApp').directive('sampleDirective', [..., function(...) {

...

}]);

// AnotherDirective.js

angular.module('myFancyApp').directive('anotherDirective', [..., function(...) {

...

}]);

// --------

/*

* InsteadOf this

*/

// Directives.js

angular.module('myFancyApp').directive('sampleDirective', [..., function(...) {

...

}]).directive('anotherDirective', [..., function(...) {

...

}]);Angular modules are defined by invoking the module function, passing through a name for the module, and the array of dependencies it must be able to inject. Afterwards, modules are got via the same function call, but giving it just the name attribute. You must avoid setting up modules more than once.

/*

* Do this only once!

*/

//Setting up a module

angular.module('myFancyApp', ['ngRoute', 'ngAnimate', ...]);

/*

* Once your module is set up, you can just get it anywhere you want

*/

// Getting the module

angular.module('myFancyApp')Using global variables is always a discouraged technique. True they will be available all along your app, but precisely, you could cause collisions among your different files. If you want more information about this topic, please go to Douglas Crockford's article on why global variables are evil.

/*

* Do this

*/

// Setting up

angular.module('myFancyApp', [...]);

// Getting

angular.module('myFancyApp')

.controller(...);

/*

* InsteadOf this

*/

// Setting up

var myFancyApp = angular.module('myFancyApp', [...]);

// Getting

myFancyApp.controller(...);

In almost every project you will be facing some feature development that doesn't belong to your project's core, or that could be otherwise extracted from central functionalities.

If you extract these features outside your core, you will ease code understanding, and you could reuse all modularised functionalities into other projects that suit, as they will be component-ready for direct-importing.

Let's assume your application needs to handle users, and you need to provide several tools for audits.

/*

* Do this

*/

angular.module('myFancyApp.users', [...]) ... // Users' stuff

angular.module('myFancyApp.tools', [...]) ... // Audit tools

angular.module('myFancyApp', ['myFancyApp.users', 'myFancyApp.tools']) ... // General stuff

/*

* InsteadOf this

*/

angular.module('myFancyApp', [...])

.directive('userStuff', function() {...})

.provider('auditTools', function() {...})When you declaring a controller within a view, you will immediately be provided with its scope, for direct use under your views (in other words, the $scope of such controller will be the namespace of the view, just as if all view were nested within a with($scope) clause).

This is cool. However, for non-complex types you could be facing reference problems when your model updates, specially if you are using a variable from an inner $scope. Your solution's name is controllerAs.

<!-- Do this -->

<div ng-controller="myFancyCtrl as fancy">

{{ fancy.variable }}

</div>

<!-- InsteadOf this -->

<div ng-controller="myFancyCtrl">

{{ variable }}

</div>This will also help you while using nested controllers, as you won't need to follow-up hierarchy to arrive at your target variable:

<!-- Do this -->

<div ng-controller="myFancyCtrl as fancy">

<div ng-controller="myChildCtrl as child">

{{ fancy.variable + child.variable }}

</div>

</div>

<!-- InsteadOf this -->

<div ng-controller="myFancyCtrl">

<div ng-controller="myChildCtrl">

{{ $parent.variable + variable }}

</div>

</div>As Angular documentation states:

Scope is an object that refers to the application model. It is an execution context for expressions. Scopes are arranged in hierarchical structure which mimic the DOM structure of the application. Scopes can watch expressions and propagate events.

Due to this $scope inheritance, all parameters defined in upper scopes will be propagated to lower ones. This could be a source of performance leaks, and you should fairly know how Angular's scopes need to work (See the guide about $scopes and the $rootScope documentation.

$rootScope is the highest-level $scope of your app. There's only one, accessible and mutable by all child controllers. Hence, every attribute and method defined within $rootScope will be propagated downwards to every single controller. Be wise about what you put inside it.

- Common, view-accessible methods

-

Configuration attributes -

Other things?

Directive's restrict parameter lets you define in which form your directive would be recognized. There are four types of directive restrictions:

E: Your directive would be a DOM element (i.e.<my-directive></my-directive>).A: You will assign the directive to an element via an html attribute (i.e.<any my-directive></any>).C: You can use a css class to identify your directive (i.e.<any class="my-directive"></any>).M: Declare your directive with a html comment (i.e.<!-- my-directive --><!-- /my-directive -->).

Using the last two is not recommended, as first could be messed-up via dynamic class assignment, and the last could (and should) be removed by your code minifier.

/*

* Do this

*/

angular.module('myFancyApp')

.directive('myDirective', function() {

return {

restrict: 'E', // or 'A' or 'EA'

...

};

});When you use element-restricted directives (i.e. E), your DOM will render a <my-directive> tag in it. While this is cool for development purposes (as it keeps the html simple and more readable) it does not comply with HTML standards, and thus some browsers (e.g. our truly loving friend IE) won't execute your application properly. The solution? Replacing directive's content.

angular.module('myFancyApp')

.directive('myDirective', function() {

return {

...

restrict: 'E',

replace: true

};

})WARNING: When using replace, the template of your directive must lay into one sole root element. Otherwise you will get an exception thrown.

NOTE: It seems that Angular has deprecated the replace attribute, and won't be available on 2.0 release. Shame on you, older IEs!

Angular directives let you declare their templates either by an inline html structure (i.e. template) or via a view's URL (i.e. templateUrl). The latter the better, as therefore you will keep each language within its proper file.

/*

* Do this

*/

angular.module('myFancyApp')

.directive('myDirective', function() {

return {

...

templateUrl: '/path/to/your/view.html'

};

})

/*

* InsteadOf this

*/

angular.module('myFancyApp')

.directive('myDirective', function() {

return {

...

template: '<div class="my-content"></div>'

};

})When your application grows big you could end up having several different directives on the very same DOM element, each of which with a duty given. In some cases you may need one particular directive to be compiled after another. For that purpose Angular gives us a directive priority configuration (see more on $compile documentation).

<div my-directive1 my-directive2></div>// Directive 1 (more priority -> compiled first)

angular.module('myFancyApp')

.directive('myDirective1', function() {

return {

...

priority: 1

};

})

// Directive 2 (less priority -> compiled last)

angular.module('myFancyApp')

.directive('myDirective2', function() {

return {

...

priority: 0

};

})Directives are directly nested down on DOM's structure, and hence on the $scope hierarchy. Thus, a directive will inherit by default all $scope attributes available on the context the directive's at.

Directive isolation lets you define which attributes the directive could use, and even tell angular how.

/*

* Do this

*/

angular.module('myFancyApp')

.directive('myDirective', function() {

return {

...

scope: {

inheritValue: '=', // Value obtained from upper scopes

plainValue: '@', // Value given directly via String

functionValue: '&', // Function call value

renamedValue: '=otherValue', // Value set up as 'other-value' within the HTML, renamed to 'renamedValue'

optionalValue: '=?' // If followed-up by a question mark, your parameter will be optional

}

};

})

/*

* InsteadOf this (full isolated scope)

*/

angular.module('myFancyApp')

.directive('myDirective', function() {

return {

...

scope: true

};

})

/*

* Or this (no isolated scope)

*/

angular.module('myFancyApp')

.directive('myDirective', function() {

return {

...

scope: false

};

})You can include controller functionality under the link or compile methods. This is on most cases enough to cover your needs.

Angular directives could also define a controller to be directly engaged to the directive's template, in which you could also include features. This is not the best practise. At least not normally.

If your directive features intention are to be shared, an explicit controller might be your solution. On any other cases, link methods will do just fine.

/*

* Do this

*/

angular.module('myFancyApp')

.directive('myDirective', function() {

return {

link: function postLink(scope, element, attrs) {

// your code

}

};

})

/*

* InsteadOf this

*/

angular.module('myFancyApp')

.directive('myDirective', function() {

return {

controller: function() {

// your code

}

};

})#Filters

Angular provides you many filters that can help you to show formatted values to the users. It's better to use these filters than process data in the controllers.

If you use date or currency filters, Angular translate automatically the values to the language you are using in your application.

E.g. the markup {{ 12 | currency }} formats the number 12 as a currency using the currency filter. The resulting value is $12.00 if you are using US language. If you are using Spanish language, result will be 12€ for the same sentence.

Sometimes you need to show certain values from the database, but you need to parse these values before showing them to the users. You must use filters for this purpose.

You can make filters to parse boolean, custom currencies or long texts values, for example:

/*

* Do this for show Yes or No instead of true or false

*/

angular.module('myFancyApp')

.filter('yesNo',['$translate', function ($translate) {

return function (input) {

var st = input ? 'YES' : 'NOT';

st = $translate('COMMON.'+st);

return st;

};

}]);

});#Services

Angular provides several kinds of services, having them some differences among each others. Angular's documentation on providers and recipes there's an explanation about the peculiarities of each type.

Factories are yet another recipe for defining a service in angular. Due to its name (and given that factories are often use to manage data) seems just reasonable to use this kind of service for such purpose.

Angular gives you a great system for managing web service connections (i.e. angular-resource). Via a $resource you can natively consume any RESTFUL service, and define all methods required for your custom operations. See the $resource documentation for further info.

As we talked before in our Config vs. Run chapter, during configuration phases not all dependency types would be available. Thus, if you need to execute some behavior on a service during your config phase, it must be a provider.

Example:

If you have a complex

localemanagement, you shall want to execute something onconfigphase (e.g. loading your languages hashes, determining default language, etcetera. Then during execution you'd also want to consume some of the behaviors defined there. A provider is just what you need.

Angular constants are mutable. Weird? Yeah, but true. It's therefore your sole responsibility to keep standard procedures and never ever modify a constant after it's defined. Values would serve you well for this mutable variables.

#Other stuff

Watch expressions engage your $scope and view together, syncing changes bi-directionally, via dirty checking. Hence, once you start using a $watcher, all changes on the view model will be reflected autommatically in the view, and vice-versa. Watchers could be defined within a view (via the double-curly syntax - i.e. {{ watcher }}), or directly declared over your $scope (i.e. $scope.$watch('scopeParam', ...)).

As using a watcher means listening to every change performed, overloading your app with an excessive amount of watchers could trigger a dramatic perfomance leak.

As stated by Ben Nadel on his article Counting the number of watchers in Angular, you must keep your watcher count under 2,000.

When you define a view, it is a plain HTML file stored apart from scripts and other resources. Thus, when Angular tries to load some view, it has to perform an XHR request to get your view loaded. ¿The problem? The timing. While your view is loading asynchronously your application will be already rendered, and hence you can feel a lack of integrity or a time-consuming loading for a single purpose.

To overcome this, Angular provides us with the $templateCache. When you request a view load, Angular first tries to resolve it's path within the cached templates. If (and only if) none is found there, an XHR request is triggered.

WARNING: Having templates cached is cool, but developing already cached templates (inline HTML) is an awkward procedure. Leverage Grunt or Gulp tasks (i.e. angular-templates or ng-templates) to compile your views at build time.

// Gruntfile.js -EXAMPLE CONFIGURATION-

...

ngtemplates: {

main: {

cwd: '<%= yeoman.app %>',

src: [ 'views/{,*/}*.html', 'templates/**/*.html' ],

dest: '<%= yeoman.dist %>/views.js',

options: {

prefix: '/', // Include a preffix to every view loaded

module: 'myFancyApp'

}

}

},

...When you deploy your app into productive environments timing is of the essence. Normal minification procedures cover the obfuscation, concatenation, minification and compression of all your resources into one file. Your JSON resources that represent static files on your filesystem shall be minified too, and even converted into an Angular-ready format (avoiding the XHR calls to retrieve them on startup). For that purpose both Grunt and Gulp offer you tools (angular-constants or ng-constants) to convert such JSON files into Angular constants that could be directly injected into your app as another dependency. Nice and neat, you're avoiding N service calls with this approach.

// Gruntfile.js -EXAMPLE CONFIGURATION-

...

ngconstant: {

options: {

space: ' ',

name: 'myFancyApp.config', // Name of the module

wrap: '"use strict";\n\n {%= __ngModule %}',

dest: '<%= yeoman.dist %>/config.js',

// Global constants

constants: {

config: { // -> Constant name

profiles: grunt.file.readJSON('app/resources/availableProfiles.json'),

global: grunt.file.readJSON('app/resources/globalConf.json'),

infoData: grunt.file.readJSON('app/resources/infoData.json'),

langList: grunt.file.readJSON('app/resources/langList.json'),

roleList: grunt.file.readJSON('app/resources/roleList.json'),

routes: grunt.file.readJSON('app/resources/routes.json')

},

i18n: { // -> Constant name

en: grunt.file.readJSON('app/i18n/en.json'),

en_US: grunt.file.readJSON('app/i18n/en_US.json'),

es: grunt.file.readJSON('app/i18n/es.json'),

es_ES: grunt.file.readJSON('app/i18n/es_ES.json'),

}

}

},

...WARNING: When injecting your i18n resources this way, you might find your texts messed-up. To overcome this, be sure the config.js file generated with such resources is loaded into the app with its proper encoding and mime-type.

NOTE: This chapter covers exclusively Angular ways of testing. There's a broad greater set of best practises on the particular Testing & QA section of the guide.

When defining unit testing, you often need to inject dependencies that won't be available on testing phases. Angular mocks let you inject such services, and train them to return sample values of your choice. Take a look at Angular's unit testing documentation for fully detailed information.

Angular mocks example

// Initialize the controller and a mock scope

beforeEach(inject(function ($controller, $rootScope) {

scope = $rootScope.$new();

ManagementServiceManagementCtrl = $controller('ManagementServiceManagementCtrl', {

$scope: scope

// place here mocked dependencies

});

}));Karma and Jasmine let you write atomic behavioral test specs that fullify the unit testing of your app. They're awesome tools.

Sample test file

'use strict';

describe('Controller: ManagementServiceManagementCtrl', function () {

// load the controller's module

beforeEach(module('myFancyApp'));

var ManagementServiceManagementCtrl,

scope;

// Initialize the controller and a mock scope

beforeEach(inject(function ($controller, $rootScope) {

scope = $rootScope.$new();

ManagementServiceManagementCtrl = $controller('ManagementServiceManagementCtrl', {

$scope: scope

// place here mocked dependencies

});

}));

it('should attach a list of awesomeThings to the scope', function () {

expect(ManagementServiceManagementCtrl.awesomeThings.length).toBe(3);

});

});Moving around sprints of your project you stepped back at some point, leaving unused some code. Code coverage lets you graphically see what code is being run or not, once executed your unit tests. Is fully graphical and gives you great insights about your code execution.

You can use keywords to ignore several content, that wouldn't apply for general code coverage reports.

See Istanbul documentation here

E2E tests allow you to simulate user's behavior executing certain tasks. Plus is cool to see your app moving back and forth magically.

Protractor leverages web drivers (just as Selenium or other tools do) to launch your favorite web browser and execute the tasks you've automated first. With this tool you can assure compliance of all covered behaviors, which is a really handy information before deploying into production environments, at the very least.

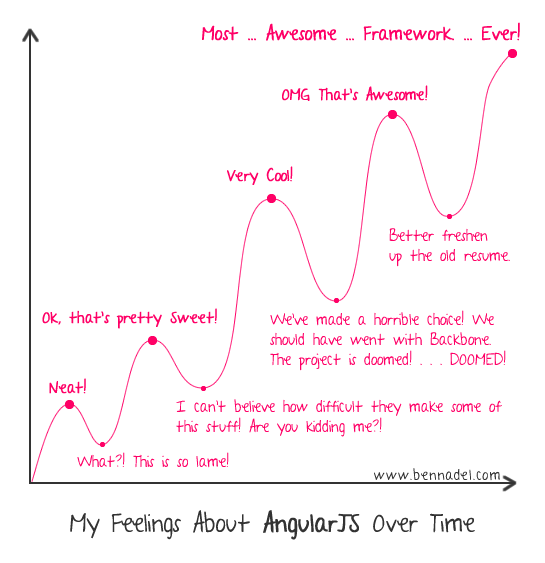

Angular is a great tool, but its learning curve could be tricky. It's full of complex stuff and it's so complete, that along with your experience gaining you'll feel stuck somewhere. Don't panic, and try to keep going. Eventually you'll overcome its rollercoaster learning curve:

Image provided by Ben Nadel on his article My experience with AngularJS

Image provided by Ben Nadel on his article My experience with AngularJS

Angular is awesome, right. But most of its awesomeness is that finding someone that had already dealt with some challenge your facing is an almost-sure thing. Plus, its documentation is neat.

Once you evolve with Angular you'll be capable of great-helping others, that could be struggling with some problem you've already solved.

We cannot say nothing about the public community, as open source contributions are completely optional and altruist, but you shall spend some time around our internal front-end community, to give and get as much as you can :).

- Angular Site API, SDK, News & Documentation

- ng-newsletter Newsletter about the angular community

- ng-book Book about Angular 1.4

- Angular John Papa's Styleguide

- [CodeSchool free MOOC] (https://www.codeschool.com/courses/shaping-up-with-angular-js)

BEEVA | 2016