Use this text to work through the tutorial if you using an IDE or SBT in a terminal. If you are using the Jupyter notebook option, the same content can be found in the 00_Tutorial.ipynb notebook.

We'll assume you've setup the tutorial as described in the README.

We'll describe the techniques used for running in an IDE and SBT. Pick the appropriate choice as described for each particular example.

For the regular Scala programs, i.e., the ones that don't use the naming convention *-script.scala, you can select the class in the project browser or the editor for the file, then invoke the IDE's run command.

Many of the examples accept command line arguments to configure behavior, but all have suitable defaults. To change the command line arguments, use IDE's tool for editing the run configuration.

Try running WordCount3. Note the output directory listed in the console output; it should be output/kjv-wc3. Use a file browser or a terminal window to view the output in that directory. You should find a _SUCCESS and a part-00000 file. Following Hadoop conventions, the latter contains the actual data for the "partitions" (in this case just one, the 00000 partition). The _SUCCESS file is empty. It is written when output to the part-NNNNN files is completed, so that other applications watching the directory know the process is done and it's safe to read the data.

For the "script" files, i.e., those use the naming convention *-script.scala, they are designed to be run in the Spark Shell, which we have simulated with our configuration of SBT.

To run these scripts, use the sbt console command discussed in the SBT section below or the equivalent within your IDE. It's not sufficient to just run a "generic" Scala REPL (interpreter), because you need the libraries and expressions setup as part of the SBT project for the console.

Or you can download the Spark 2.2.0 distribution, expand it somewhere, and start the $SPARK_HOME/bin/spark-shell (use this project's working directory as your starting point). Then load the script file as follows at the scala> prompt:

scala> :load src/main/scala/sparktutorial/Intro1-script.scala

...

scala>You can also copy and paste individual lines, but be careful about using the correct "paste" conventions required by the Scala interpreter. See here for details.

There's no real need to start the shell first; the following command just passes the script to the spark-shell on invocation.

$SPARK_HOME/bin/spark-shell src/main/scala/sparktutorial/Intro1-script.scala

...It's easiest to work at the SBT prompt. Start sbt and you'll arrive at the prompt sbt:spark-scala-tutorial>.

To run an executable program, use one of the following:

sbt:spark-scala-tutorial> runMain WordCount3

...

or have SBT prompt you for the executable to run:

sbt:spark-scala-tutorial> run

Multiple main classes detected, select one to run:

[1] Crawl5a

[2] Crawl5aLocal

...

Enter number:

Enter a number to pick WordCount3 and hit RETURN. Unfortunately, the programs are not listed in alphabetical order, nor is your order guaranteed to match the order I see!

Tip: Change your mind? Enter an invalid number and it will stop.

Finally, most of the programs have command aliases defined in build.sbt for runMain Foo. For example, ex3 runs runMain WordCount3.

Note the output directory listed in the console output. If you picked WordCount3, it will be output/kjv-wc3. Use a file browser or a terminal window to view the output in that directory. You should find a _SUCCESS and a part-00000 file. Following Hadoop conventions, the latter contains the actual data for the "partitions" (in this case just one, the 00000 partition). The _SUCCESS file is empty. It is written when output to the part-NNNNN files is completed, so that other applications watching the directory know the process is done and it's safe to read the data.

The script files, i.e., those using the naming convention *-script.scala, are designed to be run in the Spark Shell, but we have configured the SBT "console" to simulate the shell. The following example starts the console from the SBT prompt and loads one of the scripts at the scala> prompt:

sbt:spark-scala-tutorial> console

...

scala> :load src/main/scala/sparktutorial/Intro1-script.scala

...

scala>

We're using a few conventions for the package structure and main class names:

FooBarN.scala- TheFooBarcompiled program for the N^th^ example.FooBarN-script.scala- TheFooBarscript for the N^th^ example. It is run using thespark-shellor the SBTconsole, as described above.solns/FooBarNSomeExercise.scala- The solution to the "some exercise" exercise that's described inFooBarN.scala. These programs are also invoked in the same ways.

Otherwise, we don't use package prefixes, but only because they tend to be inconvenient. Most production code should use packages, of course.

Let's start with an overview of Spark, then discuss how to setup and use this tutorial.

Apache Spark is a distributed computing system written in Scala for distributed data programming. Besides Scala, you can program Spark using Java, Python, R, and SQL! This tutorial focuses on Scala and SQL.

Spark includes support for stream processing, using an older DStream or a newer Structured Streaming backend, as well as more traditional batch-mode applications.

Note: The streaming examples in this tutorial use the older library. Newer examples are TODO.

There is a SQL module for working with data sets through SQL queries or a SQL-like API. It integrates the core Spark API with embedded SQL queries with defined schemas. It also offers Hive integration so you can query existing Hive tables, even create and delete them. Finally, it supports a variety of file formats, including CSV, JSON, Parquet, ORC, etc.

There is also an interactive shell, which is an enhanced version of the Scala REPL (read, eval, print loop shell).

By 2013, it became increasingly clear that a successor was needed for the venerable Hadoop MapReduce compute engine. MapReduce applications are difficult to write, but more importantly, MapReduce has significant performance limitations and it can't support event-streaming ("real-time") scenarios.

Spark was seen as the best, general-purpose alternative, so all the major Hadoop vendors announced support for it in their distributions.

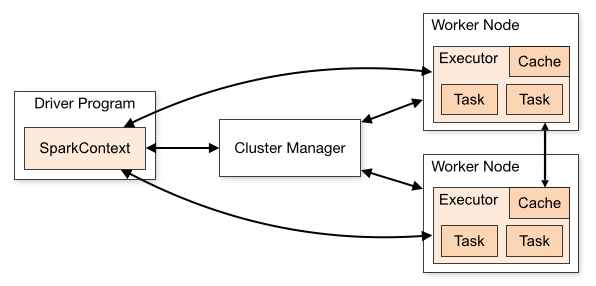

Let's briefly discuss the anatomy of a Spark cluster, adapting this discussion (and diagram) from the Spark documentation. Consider the following diagram:

Each program we'll write is a Driver Program. It uses a SparkContext to communicate with the Cluster Manager, which is an abstraction over Hadoop YARN, Mesos, standalone (static cluster) mode, EC2, and local mode.

The Cluster Manager allocates resources. An Executor JVM process is created on each worker node per client application. It manages local resources, such as the cache (see below) and it runs tasks, which are provided by your program in the form of Java jar files or Python scripts.

Because each application has its own executor process per node, applications can't share data through the Spark Context. External storage has to be used (e.g., the file system, a database, a message queue, etc.)

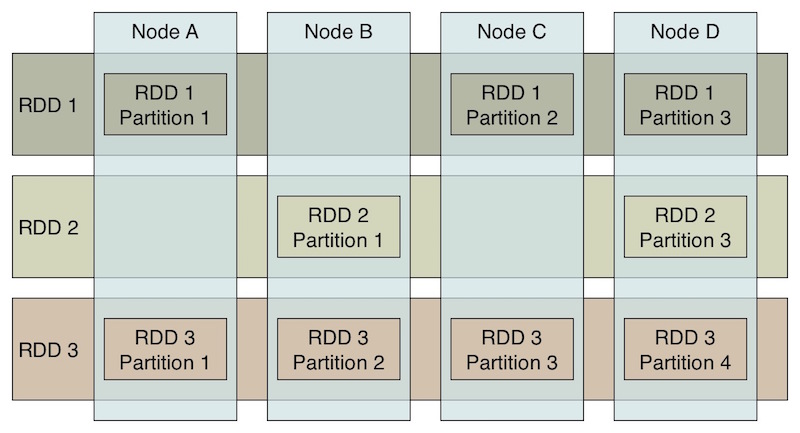

The data caching is one of the key reasons that Spark's performance is considerably better than the performance of MapReduce. Spark stores the data for the job in Resilient, Distributed Datasets (RDDs), where a logical data set is partitioned over the cluster.

The user can specify that data in an RDD should be cached in memory for subsequent reuse. In contrast, MapReduce has no such mechanism, so a complex job requiring a sequence of MapReduce jobs will be penalized by a complete flush to disk of intermediate data, followed by a subsequent reloading into memory by the next job.

RDDs support common data operations, such as map, flatmap, filter, fold/reduce, and groupby. RDDs are resilient in the sense that if a "partition" of data is lost on one node, it can be reconstructed from the original source without having to start the whole job over again.

The architecture of RDDs is described in the research paper Resilient Distributed Datasets: A Fault-Tolerant Abstraction for In-Memory Cluster Computing.

SparkSQL first introduced a new DataFrame type that wraps RDDs with schema information and the ability to run SQL queries on them. A successor called Dataset removes some of the type safety "holes" in the DataFrame API, although that API is still available.

There is an integration with Hive, the original SQL tool for Hadoop, which lets you not only query Hive tables, but run DDL statements too. There is convenient support for reading and writing various formats like Parquet and JSON.

This tutorial uses Spark 2.2.0.

The following documentation links provide more information about Spark:

The Documentation includes a getting-started guide and overviews of the various major components. You'll find the Scaladocs API useful for the tutorial.

Here is a list of the examples, some of which have exercises embedded as comments. In subsequent sections, we'll dive into the details for each one. Note that each name ends with a number, indicating the order in which we'll discuss and try them:

- Intro1-script: The first example is actually run interactively as a script.

- WordCount2: The Word Count algorithm: read a corpus of documents, tokenize it into words, and count the occurrences of all the words. A classic, simple algorithm used to learn many Big Data APIs. By default, it uses a file containing the King James Version (KJV) of the Bible. (The

datadirectory has a README that discusses the sources of the data files.) - WordCount3: An alternative implementation of Word Count that uses a slightly different approach and also uses a library to handle input command-line arguments, demonstrating some idiomatic (but fairly advanced) Scala code.

- Matrix4: Demonstrates using explicit parallelism on a simplistic Matrix application.

- Crawl5a: Simulates a web crawler that builds an index of documents to words, the first step for computing the inverse index used by search engines. The documents "crawled" are sample emails from the Enron email dataset, each of which has been classified already as SPAM or HAM.

- InvertedIndex5b: Using the crawl data, compute the index of words to documents (emails).

- NGrams6: Find all N-word ("NGram") occurrences matching a pattern. In this case, the default is the 4-word phrases in the King James Version of the Bible of the form

% love % %, where the%are wild cards. In other words, all 4-grams are found withloveas the second word. The%are conveniences; the NGram Phrase can also be a regular expression, e.g.,% (hat|lov)ed? % %finds all the phrases withlove,loved,hate, andhated. - Joins7: Spark supports SQL-style joins as shown in this simple example. Note this RDD approach is obsolete; use the SparkSQL alternatives.

- SparkSQL8: Uses the SQL API to run basic queries over structured data in

DataFrames, in this case, the same King James Version (KJV) of the Bible used in the previous tutorial. There is also a script version of this file. Using the spark-shell to do SQL queries can be very convenient! - SparkSQLFileFormats9: Demonstrates writing and reading Parquet-formatted data, namely the data written in the previous example.

- SparkStreaming10: The older structured streaming (

DStream) capability. Here it's used to construct a simplistic "echo" server. Running it is a little more involved, as discussed below.

Let's now work through these exercises...

Our first exercise demonstrates the useful Spark Shell, which is a customized version of Scala's REPL (read, eval, print, loop). It allows us to work interactively with our algorithms and data.

You can run this script, as described earlier, using either the spark-shell command in the Spark 2.2.0 distribution, or you can use the SBT console (Scala interpreter or "REPL"), which I've customized to behave in a similar way. For Hadoop, Mesos, or Kubernetes execution, you would have to use spark-shell; see the Spark Documentation for more details.

We'll copy and paste expressions from the file Intro1-script.scala. We showed above how to run it all at once.

Open the file in your favorite editor/IDE. The extensive comments in this file and the subsequent files explain the API calls in detail. You can copy and paste the comments, too.

NOTE: while the file extension is

.scala, this file is not compiled with the rest of the code, because it works like a script. The SBT compile step is configured to ignore files with names that match the pattern*-script.scala.

To run this example, start the SBT console, e.g.,

$ sbt

> console

...

scala>

Now you are at the prompt for the Scala interpreter. Note the three prompts, $ for your command-line shell, > for SBT, and scala> for the Scala interpreter. Confusing, yes, but you'll grow accustom to them.

First, there are some commented lines that every Spark program needs, but you don't need to run them in this script. Both the local Scala REPL configured in the build and the spark-shell variant of the Scala REPL execute more or less the same lines automatically at startup:

// If you're using the Spark Shell, $SPARK_HOME/bin/spark-shell, the following

// commented-out code are done automatically by the shell as it starts up.

// In this tutorial, we don't download and use a full Spark distribution.

// Instead, we'll use SBT's "console" task, but we'll configure it to use the

// same commands that spark-shell uses (more or less...).

// import org.apache.spark.sql.SparkSession

// import org.apache.spark.SparkContext

// val spark = SparkSession.builder.

// master("local[*]").

// appName("Console").

// config("spark.app.id", "Console"). // to silence Metrics warning

// getOrCreate()

// val sc = spark.sparkContext

// val sqlContext = spark.sqlContext

// import sqlContext.implicits._

// import org.apache.spark.sql.functions._ // for min, max, etc.The SparkSession drives everything else. Before Spark 2.0, the SparkContext was the entry point. You can still extract it from the SparkSession as shown near the end, for convenience.

The SparkSession.builder uses the common builder pattern to construct the session object. Note that value passed to master. The setting local[*] says run locally on this machine, but take all available CPU cores. Replace * with a number to limit this to fewer cores. Just using local limits execution to 1 core. There are different arguments you would use for Hadoop, Mesos, Kubernetes, etc.

Next we define a read-only variable input of type RDD by loading the text of the King James Version of the Bible, which has each verse on a line, we then map over the lines converting the text to lower case:

val input = sc.textFile("data/kjvdat.txt").map(line => line.toLowerCase)More accurately, the type of input is RDD[String] (or RDD<String> in Java syntax). Think of it as a "collection of strings".

The

datadirectory has aREADMEthat discusses the files present and where they came from.

Then, we cache the data in memory for faster, repeated retrieval. You shouldn't always do this, as it's wasteful for data that's simply passed through, but when your workflow will repeatedly reread the data, caching provides performance improvements.

input.cacheNext, we filter the input for just those verses that mention "sin" (recall that the text is now lower case). Then count how many were found.

val sins = input.filter(line => line.contains("sin"))

val count = sins.count() // How many sins?Next, convert the RDD to a Scala collection (in the memory for the driver process JVM). Finally, loop through the first twenty lines of the array, printing each one, then we do this again with the RDD itself.

val array = sins.collect() // Convert the RDD into a collection (array)

array.take(20).foreach(println) // Take the first 20, loop through them, and print them 1 per line.

sins.take(20).foreach(println) // ... but we don't have to "collect" first;

// we can just use foreach on the RDD.Continuing, you can define functions as values. Here we create a separate filter function that we pass as an argument to the filter method. Previously we used an anonymous function. Note that filterFunc is a value that's a function of type String to Boolean.

val filterFunc: String => Boolean =

(s:String) => s.contains("god") || s.contains("christ")The following more concise form is equivalent, due to type inference of the argument's type:

val filterFunc: String => Boolean =

s => s.contains("god") || s.contains("christ")Now use the filter to find all the sin verses that also mention God or Christ, then count them. Note that this time, we drop the "punctuation" in the first line (the comment shows what we dropped), and we drop the parentheses after "count". Parentheses can be omitted when methods take no arguments.

val sinsPlusGodOrChrist = sins filter filterFunc // same as: sins.filter(filterFunc)

val countPlusGodOrChrist = sinsPlusGodOrChrist.countFinally, let's do Word Count, where we load a corpus of documents, tokenize them into words and count the occurrences of all the words.

First, we'll define a helper method to look at the data. We need to import the RDD type:

import org.apache.spark.rdd.RDD

def peek(rdd: RDD[_], n: Int = 10): Unit = {

println("RDD type signature: "+rdd+"\n")

println("=====================")

rdd.take(n).foreach(println)

println("=====================")

}In the type signature RDD[_], the _ means "any type". In other words, we don't care what records this RDD is holding, because we're just going to call toString on each one. The second argument n is the number of records to print. It has a default value of 10, which means if the caller doesn't provide this argument, we'll print 10 records.

The peek function prints the type of the RDD by calling toString on it (effectively). Then it takes the first n records, loops through them, and prints each one on a line.

Let's use peek to remind ourselves what the input value is. For this and the next few lines, I'll put in the scala> prompt, followed by the output:

scala> input

res27: org.apache.spark.rdd.RDD[String] = MapPartitionsRDD[9] at map at <console>:20

scala> peek(input)

=====================

gen|1|1| in the beginning god created the heaven and the earth.~

gen|1|2| and the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. and the spirit of god moved upon the face of the waters.~

gen|1|3| and god said, let there be light: and there was light.~

gen|1|4| and god saw the light, that it was good: and god divided the light from the darkness.~

gen|1|5| and god called the light day, and the darkness he called night. and the evening and the morning were the first day.~

gen|1|6| and god said, let there be a firmament in the midst of the waters, and let it divide the waters from the waters.~

gen|1|7| and god made the firmament, and divided the waters which were under the firmament from the waters which were above the firmament: and it was so.~

gen|1|8| and god called the firmament heaven. and the evening and the morning were the second day.~

gen|1|9| and god said, let the waters under the heaven be gathered together unto one place, and let the dry land appear: and it was so.~

gen|1|10| and god called the dry land earth; and the gathering together of the waters called he seas: and god saw that it was good.~

=====================Note that input is a subtype of RDD called MapPartitionsRDD. and the RDD[String] means the "records" are just strings. (You might see a different name than res27.) You might confirm for yourself that the lines shown by peek(input) match the input data file.

Now, let's split each line into words. We'll treat any run of characters that don't include alphanumeric characters as the "delimiter":

scala> val words = input.flatMap(line => line.split("""[^\p{IsAlphabetic}]+"""))

words: org.apache.spark.rdd.RDD[String] = MapPartitionsRDD[25] at flatMap at <console>:22

scala> peek(words)

=====================

gen

in

the

beginning

god

created

the

heaven

and

the

=====================Does the output make sense to you? The type of the RDD hasn't changed, but the records are now individual words.

Now let's use our friend from SQL, GROUPBY, where we use the words as the "keys":

scala> val wordGroups = words.groupBy(word => word)

wordGroups: org.apache.spark.rdd.RDD[(String, Iterable[String])] = ShuffledRDD[27] at groupBy at <console>:23

scala> peek(wordGroups)

=====================

(winefat,CompactBuffer(winefat, winefat))

(honeycomb,CompactBuffer(honeycomb, honeycomb, honeycomb, honeycomb, honeycomb, honeycomb, honeycomb, honeycomb, honeycomb))

(bone,CompactBuffer(bone, bone, bone, bone, bone, bone, bone, bone, bone, bone, bone, bone, bone, bone, bone, bone, bone, bone, bone))

(glorifying,CompactBuffer(glorifying, glorifying, glorifying))

(nobleman,CompactBuffer(nobleman, nobleman, nobleman))

(hodaviah,CompactBuffer(hodaviah, hodaviah, hodaviah))

(raphu,CompactBuffer(raphu))

(hem,CompactBuffer(hem, hem, hem, hem, hem, hem, hem))

(onyx,CompactBuffer(onyx, onyx, onyx, onyx, onyx, onyx, onyx, onyx, onyx, onyx, onyx))

(pigeon,CompactBuffer(pigeon, pigeon))

=====================Note that the records are now two-element Tuples: (String, Iterable[String]), where Iterable is a Scala abstraction for an underlying, sequential collection. We see that these iterables are CompactBuffers, a Spark collection that wraps an array of objects. Note that these buffers just hold repeated occurrences of the corresponding keys. This is wasteful, especially at scale! We'll learn a better way to do this calculation shortly.

Finally, let's compute the size of each CompactBuffer, which completes the calculation of how many occurrences are there for each word:

scala> val wordCounts1 = wordGroups.map( word_group => (word_group._1, word_group._2.size))

wordCounts1: org.apache.spark.rdd.RDD[(String, Int)] = MapPartitionsRDD[28] at map at <console>:24

scala> peek(wordCounts1)

=====================

(winefat,2)

(honeycomb,9)

(bone,19)

(glorifying,3)

(nobleman,3)

(hodaviah,3)

(raphu,1)

(hem,7)

(onyx,11)

(pigeon,2)

=====================Note that the function passed to map expects a single two-element Tuple argument. We extract the two elements using the _1 and _2 methods. (Tuples index from 1, rather than 0, following historical convention.) The type of wordCounts1 is RDD[(String,Int)].

There is a more concise syntax we can use for the method, which exploits pattern matching to break up the tuple into its constituents, which are then assigned to the value names:

scala> val wordCounts2 = wordGroups.map{ case (word, group) => (word, group.size) }

wordCounts2: org.apache.spark.rdd.RDD[(String, Int)] = MapPartitionsRDD[28] at map at <console>:24

scala> peek(wordCounts2)

=====================

(winefat,2)

(honeycomb,9)

(bone,19)

(glorifying,3)

(nobleman,3)

(hodaviah,3)

(raphu,1)

(hem,7)

(onyx,11)

(pigeon,2)

=====================The results are exactly the same.

But there is actually an even easier way. Note that we aren't modifying the

keys (the words), so we can use a convenience function mapValues, where only

the value part (second tuple element) is passed to the anonymous function and

the keys are retained:

scala> val wordCounts3 = wordGroups.mapValues(group => group.size)

wordCounts3: org.apache.spark.rdd.RDD[(String, Int)] = MapPartitionsRDD[31] at mapValues at <console>:24

scala> peek(wordCounts3)

// same as beforeFinally, let's save the results to the file system:

wordCounts3.saveAsTextFile("output/kjv-wc-groupby")If you look in the directory output/kjv-wc-groupby, you'll see three files:

_SUCCESS

part-00000

part-00001

The _SUCCESS file is empty. It's a marker used by the Hadoop File I/O libraries (which Spark uses) to signal to waiting processes that the file output has completed. The other two files each hold a partition of the data. In this case, we had two partitions.

We're done, but let's finish by noting that a non-script program should shutdown gracefully by calling spark.stop(). However, we don't need to do so here, because both our configured console environment for local execution and spark-shell do this for us:

// spark.stop()If you exit the REPL immediately, this will happen implicitly. Still, it's a good practice to always call stop. Don't do this now; we want to keep the session alive...

When you have a SparkContext running, it provides a web UI with very useful information about how your job is mapped to JVM tasks, metrics about execution, etc.

Before we finish this exercise, open localhost:4040 and browse the UI. You will find this console very useful for learning Spark internals and when debugging problems.

There are comments at the end of this file with suggested exercises to learn the API. All the subsequent examples we'll discuss include suggested exercises, too.

Solutions for some of the suggested exercises are provided in the src/main/scala/sparktutorial/solns directory (athough not for this script's suggestions).

You can exit the Scala REPL now. Type :quit or use ^d (control-d - which means "end of input" for *NIX systems.).

The classic, simple Word Count algorithm is easy to understand and it's suitable for parallel computation, so it's a good vehicle when first learning a Big Data API.

In Word Count, you read a corpus of documents, tokenize each one into words, and count the occurrences of all the words globally.

WordCount2.scala uses the KJV Bible text again. (Subsequent exercises will add the ability to specify different input sources using command-line arguments.)

Use your IDE's run command for the file or use SBT to run it. For SBT, use one of the following three methods:

- Enter the

runcommand at thesbtprompt and select the number corresponding to theWordCount2program. - Enter

runMain WordCount2 - Enter

ex2, a command alias forrunMain WordCount2. (The alias is defined in the project's./build.sbtfile.)

Either way, the output is written to output/kjv-wc2 in the local file system. Use a file browser or another terminal window to view the files in this directory. You'll find an empty _SUCCESS file that marks completion and a part-00000 file that contains the data.

As before, here is the text of the script in sections, with code comments removed:

import util.FileUtil

import org.apache.spark.SparkContext

import org.apache.spark.SparkContext._We use the Java default package for the compiled exercises, but you would normally include a package ... statement to organize your applications into packages, in the usual Java way.

We import a FileUtil class that we'll use for "housekeeping". Then we use two SparkContext imports. The first one imports the type, the second imports items inside the companion object, for convenience.

Even though most of the examples and exercises from now on will be compiled classes, you could still use the Spark Shell to try out most constructs. This is especially useful when experimenting and debugging!

Here is the outline of the rest of the program, demonstrating a pattern we'll use throughout.

object WordCount2 {

def main(args: Array[String]): Unit = {

val sc = new SparkContext("local", "Word Count (2)")

try {

...

} finally {

sc.stop() // Stop (shut down) the context.

}

}

}In case the script fails with an exception, putting the SparkContext.stop() inside a finally clause ensures that we'll properly clean up no matter what happens.

The content of the try clause is the following:

val out = "output/kjv-wc2"

FileUtil.rmrf(out) // Delete old output (if any)

val input = sc.textFile("data/kjvdat.txt").map(line => line.toLowerCase)

input.cache

val wc = input

.flatMap(line => line.split("""[^\p{IsAlphabetic}]+"""))

.map(word => (word, 1))

.reduceByKey((count1, count2) => count1 + count2)

println(s"Writing output to: $out")

wc.saveAsTextFile(out)Because Spark follows Hadoop conventions that it won't overwrite existing data, we delete any previous output, if any. Of course, you should only do this in production jobs when you know it's okay!

Next we load and cache the data like we did previously, but this time, it's questionable whether caching is useful, since we will make a single pass through the data. I left this statement here just to remind you of this feature.

Now we setup a pipeline of operations to perform the word count.

First the line is split into words using as the separator any run of characters that isn't alphabetic, e.g., digits, whitespace, and punctuation. (Note: using "\\W+" doesn't work well for non-UTF8 character sets!) This also conveniently removes the trailing ~ characters at the end of each line that exist in the file for some reason. input.flatMap(line => line.split(...)) maps over each line, expanding it into a collection of words, yielding a collection of collections of words. The flat part flattens those nested collections into a single, "flat" collection of words.

The next two lines convert the single word "records" into tuples with the word and a count of 1. In Spark, the first field in a tuple will be used as the default key for joins, group-bys, and the reduceByKey we use next.

The reduceByKey step effectively groups all the tuples together with the same word (the key) and then "reduces" the values using the passed in function. In this case, the two counts are added together. Hence, we get two-element records with unique words and their counts.

Finally, we invoke saveAsTextFile to write the final RDD to the output location.

Note that the input and output locations will be relative to the local file system, when running in local mode, and relative to the user's home directory in HDFS (e.g., /user/$USER), when a program runs in Hadoop.

Spark also follows another Hadoop convention for file I/O; the out path is actually interpreted as a directory name. It will contain the same _SUCCESS and part-00000 files discussed previously. In a real cluster with lots of data and lots of concurrent tasks, there would be many part-NNNNN files.

Quiz: If you look at the (unsorted) data, you'll find a lot of entries where the word is a number. (Try searching the input text file to find them.) Are there really that many numbers in the bible? If not, where did the numbers come from? Look at the original file for clues.

At the end of each example source file, you'll find exercises you can try. Solutions for some of them are implemented in the solns package. For example, solns/WordCount2GroupBy.scala solves the "group by" exercise described in WordCount2.scala.

This exercise also implements Word Count, but it uses a slightly simpler approach. It also uses a utility library to support command-line arguments, demonstrating some idiomatic (but fairly advanced) Scala code. We won't worry about the details of this utility code, just how to use it. Next, instead of using the old approach of creating a SparkContext, we'll use the new approach of creating a SparkSession and extracting the SparkContext from it when needed. Finally, we'll also use Kryo Serialization, which provides better compression and therefore better utilization of memory and network bandwidth (not that we really need it for this small dataset...).

This version also does some data cleansing to improve the results. The sacred text files included in the data directory, such as kjvdat.txt are actually formatted records of the form:

book|chapter#|verse#|text

That is, pipe-separated fields with the book of the Bible (e.g., Genesis, but abbreviated "Gen"), the chapter and verse numbers, and then the verse text. We just want to count words in the verses, although including the book names wouldn't change the results significantly. (Now you can figure out the answer to the "quiz" in the previous section...)

Using SBT, do one of the following:

- Enter the

runcommand and select the number corresponding to theWordCount3program. - Enter

runMain WordCount3 - Enter

ex3, a command alias forrunMain WordCount3.

Command line options can be used to override the default settings for input and output locations, among other things. You can specify arguments after the run, runMain ..., or ex3 commands.

Here is the help message that lists the available options. The "" characters indicate long lines that are wrapped to fit. Enter the commands on a single line without the "". Following Unix conventions, [...] indicates optional arguments, and | indicates alternatives:

runMain WordCount3 [ -h | --help] \

[-i | --in | --inpath input] \

[-o | --out | --outpath output] \

[-m | --master master] \

[-q | --quiet]

Where the options have the following meanings:

-h | --help Show help and exit.

-i ... input Read this input source (default: data/kjvdat.txt).

-o ... output Write to this output location (default: output/kjvdat-wc3).

-m ... master local, local[k], yarn-client, etc., as discussed previously.

-q | --quiet Suppress some informational output.

Try running ex3 -h to see the help message.

When running in Hadoop, relative file paths for input our output are interpreted to be relative to /user/$USER in HDFS.

Here is an example that uses the default values for the options:

runMain WordCount3 \

--inpath data/kjvdat.txt --outpath output/kjv-wc3 \

--master local

You can try different variants of local[k] for the master option, but keep k less than the number of cores in your machine or use *.

When you specify an input path for Spark, you can specify bash-style "globs" and even a list of them:

data/foo: Just the filefooor if it's a directory, all its files, one level deep (unless the program does some extra handling itself).data/foo*.txt: All files indatawhose names start withfooand end with the.txtextension.data/foo*.txt,data2/bar*.dat: A comma-separated list of globs.

Okay, with all the invocation options out of the way, let's walk through the implementation of WordCount3.

We start with import statements:

import util.{CommandLineOptions, FileUtil, TextUtil}

import org.apache.spark.sql.SparkSession

import org.apache.spark.SparkContextAs before, but with our new CommandLineOptions utilities added.

object WordCount3 {

def main(args: Array[String]): Unit = {

val options = CommandLineOptions(

this.getClass.getSimpleName,

CommandLineOptions.inputPath("data/kjvdat.txt"),

CommandLineOptions.outputPath("output/kjv-wc3"),

CommandLineOptions.master("local"),

CommandLineOptions.quiet)

val argz = options(args.toList)

val master = argz("master")

val quiet = argz("quiet").toBoolean

val in = argz("input-path")

val out = argz("output-path")I won't discuss the implementation of CommandLineOptions.scala except to say that it defines some methods that create instances of an Opt type, one for each of the options we discussed above. The single argument given to some of the methods (e.g., CommandLineOptions.inputPath("data/kjvdat.txt")) specifies the default value for that option.

After parsing the options, we extract some of the values we need.

Next, if we're running in local mode, we delete the old output, if any:

if (master.startsWith("local")) {

if (!quiet) println(s" **** Deleting old output (if any), $out:")

FileUtil.rmrf(out)

}Note that this logic is only invoked in local mode, because FileUtil only works locally. We also delete old data from HDFS when running in Hadoop, but deletion is handled through a different mechanism, as we'll see shortly.

Now we create a SparkSession, the new way (since Spark 2.0) to create a Spark job. It encompasses both the older SparkContext and the SQLContext. Note we turn on Kryo serialization.

val name = "Word Count (3)"

val spark = SparkSession.builder.

master(master).

appName(name).

config("spark.app.id", name). // To silence Metrics warning.

config("spark.serializer", "org.apache.spark.serializer.KryoSerializer").

getOrCreate()

val sc = spark.sparkContextIf the data had a custom type, we would want to register it with Kryo, which already handles common types, like String, which is all we use here for "records". For serializing your classes, replace this line:

config("spark.serializer", "org.apache.spark.serializer.KryoSerializer").with this line:

registerKryoClasses(Array(classOf[MyCustomClass])).Actually, it's harmless to leave in the config("spark.serializer", ...), but it's done for you inside registerKryoClasses.

Now we process the input as before, with a few changes...

try {

val input = sc.textFile(in)

.map(line => TextUtil.toText(line)) // also converts to lower caseIt starts out much like WordCount2, but it uses a helper method TextUtil.toText to split each line from the religious texts into fields, where the lines are of the form: book|chapter#|verse#|text. The | is the field delimiter. However, if other inputs are used, their text is returned unmodified. As before, the input reference is an RDD.

Note that I omitted a subsequent call to input.cache as in WordCount2, because we are making a single pass through the data.

val wc2a = input

.flatMap(line => line.split("""[^\p{IsAlphabetic}]+"""))

.countByValue() // Returns a Map[T, Long]Take input and split on non-alphabetic sequences of character as we did in WordCount2, but rather than map to (word, 1) tuples and use reduceByKey, we simply treat the words as values and call countByValue to count the unique occurrences. Hence, this is a simpler and more efficient approach.

val wc2b = wc2a.map(key_value => s"${key_value._1},${key_value._2}").toSeq

val wc2 = sc.makeRDD(wc2b, 1)

if (!quiet) println(s"Writing output to: $out")

wc2.saveAsTextFile(out)

} finally {

spark.stop() // was sc.stop() in WordCount2

}

}

}The result of countByValue is a Scala Map, not an RDD, so we format the key-value pairs into a sequence of strings in comma-separated value (CSV) format. The we convert this sequence back to an RDD with makeRDD. Finally, we save to the file system as text.

WARNING: Methods like

countByValuethat return a Scala collection will copy the entire object back to the driver program. This could crash your application with an OutOfMemory exception if the collection is too big!

Don't forget the try the exercises at the end of the source file.

An early use for Spark was implementing Machine Learning algorithms. Spark's MLlib of algorithms contains classes for vectors and matrices, which are important for many ML algorithms. This exercise uses a simpler representation of matrices to explore another topic; explicit parallelism.

The sample data is generated internally; there is no input that is read. The output is written to the file system as before.

Here is the runMain command with optional arguments:

runMain Matrix4 [ -h | --help] \

[-d | --dims NxM] \

[-o | --out | --outpath output] \

[-m | --master master] \

[-q | --quiet]The one new option is for specifying the dimensions, where the string NxM is parsed to mean N rows and M columns. The default is 5x10.

Like for WordCount3, there is also a ex4 shortcut for runMain Matrix4.

Here is how to run this example:

runMain Matrix4 \

--master local --outpath output/matrix4

We won't cover all the code from now on; we'll skip the familiar stuff:

import util.Matrix

...

object Matrix4 {

case class Dimensions(m: Int, n: Int)

def main(args: Array[String]): Unit = {

val options = CommandLineOptions(...)

val argz = options(args.toList)

...

val dimsRE = """(\d+)\s*x\s*(\d+)""".r

val dimensions = argz("dims") match {

case dimsRE(m, n) => Dimensions(m.toInt, n.toInt)

case s =>

println("""Expected matrix dimensions 'NxM', but got this: $s""")

sys.exit(1)

}Dimensions is a convenience class for capturing the default or user-specified matrix dimensions. We parse the argument string to extract N and M, then construct a Dimension instance.

val sc = spark.sparkContext

try {

// Set up a mxn matrix of numbers.

val matrix = Matrix(dimensions.m, dimensions.n)

// Average rows of the matrix in parallel:

val sums_avgs = sc.parallelize(1 to dimensions.m).map { i =>

// Matrix indices count from 0.

// "_ + _" is the same as "(count1, count2) => count1 + count2".

val sum = matrix(i-1) reduce (_ + _)

(sum, sum/dimensions.n)

}.collect // convert to an arrayThe core of this example is the use of SparkContext.parallelize to process each row in parallel (subject to the available cores on the machine or cluster, of course). In this case, we sum the values in each row and compute the average.

The argument to parallelize is a sequence of "things" where each one will be passed to one of the operations. Here, we just use the literal syntax to construct a sequence of integers from 1 to the number of rows. When the anonymous function is called, one of those row numbers will get assigned to i. We then grab the i-1 row (because of zero indexing) and use the reduce method to sum the column elements. A final tuple with the sum and the average is returned.

// Make a new sequence of strings with the formatted output, then we'll

// dump to the output location.

val outputLines = Vector( // Scala's Vector, not MLlib's version!

s"${dimensions.m}x${dimensions.n} Matrix:") ++ sums_avgs.zipWithIndex.map {

case ((sum, avg), index) =>

f"Row #${index}%2d: Sum = ${sum}%4d, Avg = ${avg}%3d"

}

val output = sc.makeRDD(outputLines) // convert back to an RDD

if (!quiet) println(s"Writing output to: $out")

output.saveAsTextFile(out)

} finally { ... }

}

}The output is formatted as a sequence of strings and converted back to an RDD for output. The expression sums_avgs.zipWithIndex creates a tuple with each sums_avgs value and it's index into the collection. We use that to add the row index to the output.

Try the simple exercises at the end of the source file.

The fifth example is in two-parts. The first part simulates a web crawler that builds an index of documents to words, the first step for computing the inverted index used by search engines, from words to documents. The documents "crawled" are sample emails from the Enron email dataset, each of which has been previously classified already as SPAM or HAM.

Crawl5a supports the same command-line options as WordCount3:

runMain Crawl5a [ -h | --help] \

[-i | --in | --inpath input] \

[-o | --out | --outpath output] \

[-m | --master master] \

[-q | --quiet]Run with runMain Crawl5a, or the ex5a alias:

runMain Crawl5a \

--outpath output/crawl --master local

Crawl5a uses a convenient SparkContext method called wholeTextFiles, which is given a directory "glob". The default we use is data/enron-spam-ham/*, which expands to data/enron-spam-ham/ham100 and data/enron-spam-ham/spam100. This method returns records of the form (file_name, file_contents), where the file_name is the absolute path to a file found in one of the directories, and file_contents contains its contents, including nested linefeeds. To make it easier to run unit tests, Crawl5a strips off the leading path elements in the file name (not normally recommended) and it removes the embedded linefeeds, so that each final record is on a single line.

Here is an example line from the output:

(0038.2001-08-05.SA_and_HP.spam.txt, Subject: free foreign currency newsletter ...)The next step has to parse this data to generate the inverted index.

Note: There is also an older

Crawl5aLocalincluded but no longer used. It works similarly, but for local file systems only.

Using the crawl data just generated, compute the index of words to documents (emails). This is a simple approach to building a data set that could be used by a search engine. Each record will have two fields, a word and a list of tuples of documents where the word occurs and a count of the occurrences in the document.

InvertedIndex5b supports the usual command-line options:

runMain InvertedIndex5b [ -h | --help] \

[-i | --in | --inpath input] \

[-o | --out | --outpath output] \

[-m | --master master] \

[-q | --quiet]+Run with runMain InvertedIndex5b, or the ex5b alias:

runMain InvertedIndex5b \

--outpath output/inverted-index --master local

The code outside the try clause follows the usual pattern, so we'll focus on the contents of the try clause:

try {

val lineRE = """^\s*\(([^,]+),(.*)\)\s*$""".r

val input = sc.textFile(argz("input-path")) map {

case lineRE(name, text) => (name.trim, text.toLowerCase)

case badLine =>

Console.err.println("Unexpected line: $badLine")

("", "")

}We load the "crawl" data, where each line was written by Crawl5a with the following format: (document_id, text) (including the parentheses). Hence, we use a regular expression with "capture groups" to extract the document_id and text.

Note the function passed to map. It has the form:

{

case lineRE(name, text) => ...

case line => ...

}There is now explicit argument list like we've used before. This syntax is the literal syntax for a partial function, a mathematical concept for a function that is not defined at all of its inputs. It is implemented with Scala's PartialFunction type.

We have two case match clauses, one for when the regular expression successfully matches and returns the capture groups into variables name and text and the second which will match everything else, assigning the line to the variable badLine. (In fact, this catch-all clause makes the function total, not partial.) The function must return a two-element tuple, so the catch clause simply returns ("","").

Note that the specified or default input-path is a directory with Hadoop-style content, as discussed previously. Spark knows to ignore the "hidden" files.

The embedded comments in the rest of the code explains each step:

if (!quiet) println(s"Writing output to: $out")

// Split on non-alphabetic sequences of character as before.

// Rather than map to "(word, 1)" tuples, we treat the words by values

// and count the unique occurrences.

input

.flatMap {

// all lines are two-tuples; extract the path and text into variables

// named "path" and "text".

case (path, text) =>

// If we don't trim leading whitespace, the regex split creates

// an undesired leading "" word!

text.trim.split("""[^\p{IsAlphabetic}]+""") map (word => (word, path))

}

.map {

// We're going to use the (word, path) tuple as a key for counting

// all of them that are the same. So, create a new tuple with the

// pair as the key and an initial count of "1".

case (word, path) => ((word, path), 1)

}

.reduceByKey{ // Count the equal (word, path) pairs, as before

(count1, count2) => count1 + count2

}

.map { // Rearrange the tuples; word is now the key we want.

case ((word, path), n) => (word, (path, n))

}

.groupByKey // There is a also a more general groupBy

// reformat the output; make a string of each group,

// a sequence, "(path1, n1) (path2, n2), (path3, n3)..."

.mapValues(iterator => iterator.mkString(", "))

// mapValues is like the following map, but more efficient, as we skip

// pattern matching on the key ("word"), etc.

// .map {

// case (word, seq) => (word, seq.mkString(", "))

// }

.saveAsTextFile(out)

} finally { ... }Each output record has the following form: (word, (doc1, n1), (doc2, n2), ...). For example, the word "ability" appears twice in one email and once in another (both SPAM):

(ability,(0018.2003-12-18.GP.spam.txt,2), (0020.2001-07-28.SA_and_HP.spam.txt,1))It's worth studying this sequence of transformations to understand how it works. Many problems can be solved with these techniques. You might try reading a smaller input file (say the first 5 lines of the crawl output), then hack on the script to dump the RDD after each step.

A few useful RDD methods for exploration include RDD.sample or RDD.take, to select a subset of elements. Use RDD.saveAsTextFile to write to a file or use RDD.collect to convert the RDD data into a "regular" Scala collection (don't use for massive data sets!).

In Natural Language Processing, one goal is to determine the sentiment or meaning of text. One technique that helps do this is to locate the most frequently-occurring, N-word phrases, or NGrams. Longer NGrams can convey more meaning, but they occur less frequently so all of them appear important. Shorter NGrams have better statistics, but each one conveys less meaning. In most cases, N = 3-5 appears to provide the best balance.

This exercise finds all NGrams matching a user-specified pattern. The default is the 4-word phrases the form % love % %, where the % are wild cards. In other words, all 4-grams are found with love as the second word. The % are conveniences; the user can also specify an NGram Phrase that is a regular expression or a mixture, e.g., % (hat|lov)ed? % % finds all the phrases with love, loved, hate, or hated as the second word.

NGrams6 supports the same command-line options as WordCount3, plus two new options:

runMain NGrams6 [ -h | --help] \

[-i | --in | --inpath input] \

[-o | --out | --outpath output] \

[-m | --master master] \

[-c | --count N] \

[-n | --ngrams string] \

[-q | --quiet]Where

-c | --count N List the N most frequently occurring NGrams (default: 100)

-n | --ngrams string Match string (default "% love % %"). Quote the string!I'm in yür codez:

...

val ngramsStr = argz("ngrams").toLowerCase

val ngramsRE = ngramsStr.replaceAll("%", """\\w+""").replaceAll("\\s+", """\\s+""").r

val n = argz("count").toIntFrom the two new options, we get the ngrams string. Each % is replaced by a regex to match a word and whitespace is replaced by a general regex for whitespace.

try {

object CountOrdering extends Ordering[(String,Int)] {

def compare(a:(String,Int), b:(String,Int)) =

-(a._2 compare b._2) // - so that it sorts descending

}

val ngramz = sc.textFile(argz("input-path"))

.flatMap { line =>

val text = TextUtil.toText(line) // also converts to lower case

ngramsRE.findAllMatchIn(text).map(_.toString)

}

.map(ngram => (ngram, 1))

.reduceByKey((count1, count2) => count1 + count2)

.takeOrdered(n)(CountOrdering)We need an implementation of Ordering to sort our found NGrams descending by count.

We read the data as before, but note that because of our line orientation, we won't find NGrams that cross line boundaries! This doesn't matter for our sacred text files, since it wouldn't make sense to find NGrams across verse boundaries, but a more flexible implementation should account for this. Note that we also look at just the verse text, as in WordCount3.

The map and reduceByKey calls are just like we used previously for WordCount2, but now we're counting found NGrams. The takeOrdered call combines sorting with taking the top n found. This is more efficient than separate sort, then take operations. As a rule, when you see a method that does two things like this, it's usually there for efficiency reasons!

The rest of the code formats the results and converts them to a new RDD for output:

// Format the output as a sequence of strings, then convert back to

// an RDD for output.

val outputLines = Vector(

s"Found ${ngramz.size} ngrams:") ++ ngramz.map {

case (ngram, count) => "%30s\t%d".format(ngram, count)

}

val output = sc.makeRDD(outputLines) // convert back to an RDD

if (!quiet) println(s"Writing output to: $out")

output.saveAsTextFile(out)

} finally { ... }Note: This example is obsolete. Use

Dataset(SQL) joins instead. They are far more flexible and performant!

Joins are a familiar concept in databases and Spark supports them, too. Joins at very large scale can be quite expensive, although a number of optimizations have been developed, some of which require programmer intervention to use. We won't discuss the details here, but it's worth reading how joins are implemented in various Big Data systems, such as this discussion for Hive joins and the Joins section of Hadoop: The Definitive Guide.

NOTE: You will typically use the SQL/DataFrame API to do joins instead of the RDD API, because it's both easier to write them and the optimizations under the hood are better!

Here, we will join the KJV Bible data with a small "table" that maps the book abbreviations to the full names, e.g., Gen to Genesis.

Joins7 supports the following command-line options:

runMain Joins7 [ -h | --help] \

[-i | --in | --inpath input] \

[-o | --out | --outpath output] \

[-m | --master master] \

[-a | --abbreviations path] \

[-q | --quiet]Where the --abbreviations is the path to the file with book abbreviations to book names. It defaults to data/abbrevs-to-names.tsv. Note that the format is tab-separated values, which the script must handle correctly.

Here r yür codez:

...

try {

val input = sc.textFile(argz("input-path"))

.map { line =>

val ary = line.split("\\s*\\|\\s*")

(ary(0), (ary(1), ary(2), ary(3)))

}The input sacred text (default: data/kjvdat.txt) is assumed to have the format book|chapter#|verse#|text. We split on the delimiter and output a two-element tuple with the book abbreviation as the first element and a nested tuple with the other three elements. For joins, Spark wants a (key,value) tuple, which is why we use the nested tuple.

The abbreviations file is handled similarly, but the delimiter is a tab:

val abbrevs = sc.textFile(argz("abbreviations"))

.map{ line =>

val ary = line.split("\\s+", 2)

(ary(0), ary(1).trim) // I've noticed trailing whitespace...

}Note the second argument to split. Just in case a full book name has a nested tab, we explicitly only want to split on the first tab found, yielding two strings.

// Cache both RDDs in memory for fast, repeated access.

input.cache

abbrevs.cache

// Join on the key, the first field in the tuples; the book abbreviation.

val verses = input.join(abbrevs)

if (input.count != verses.count) {

println(s"input count != verses count (${input.count} != ${verses.count})")

}We perform an inner join on the keys of each RDD and add a sanity check for the output. Since this is an inner join, the sanity check catches the case where an abbreviation wasn't found and the corresponding verses were dropped!

The schema of verses is this: (key, (value1, value2)), where value1 is (chapter, verse, text) from the KJV input and value2 is the full book name, the second "field" from the abbreviations file. We now flatten the records to the final desired form, fullBookName|chapter|verse|text:

val verses2 = verses map {

// Drop the key - the abbreviated book name

case (_, ((chapter, verse, text), fullBookName)) =>

(fullBookName, chapter, verse, text)

}Lastly, we write the output:

if (!quiet) println(s"Writing output to: $out")

verses2.saveAsTextFile(out)

} finally { ... }The join method we used is implemented by spark.rdd.PairRDDFunctions, with many other methods for computing "co-groups", outer joins, etc.

You can verify that the output file looks like the input KJV file with the book abbreviations replaced with the full names. However, as currently written, the books are not retained in the correct order! (See the exercises in the source file.)

SparkSQL8.scala

SparkSQL8-script.scala

The next to last set of examples and exercises explores the SparkSQL API, which extends RDDs with the DataFrame API that adds a "schema" for records, defined using Scala case classes, tuples, or a built-in schema mechanism. The DataFrame API is inspired by similar DataFrame concepts in R and Python libraries. The transformation and action steps written in any of the support languages, as well as SQL queries embedded in strings, are translated to the same, performant query execution model, optimized by a new query engine called Catalyst.

Note: The even newer

DatasetAPI encapsulatesDataFrame, but adds more type safety for the data columns.

Tip: Even if you prefer the Scala collections-like

RDDAPI, consider using theDataFrameAPI because the performance is significantly better in most cases.

Furthermore, SparkSQL has convenient support for reading and writing files encoded using Parquet, ORC, JSON, CSV, etc.

Finally, SparkSQL embeds access to a Hive metastore, so you can create and delete tables, and run queries against them using SparkSQL.

This example treats the KJV text we've been using as a table with a schema. It runs several SQL queries on the data, then performs the same calculation using the DataFrame API.

There is a SparkSQL8.scala program that you can run as before using SBT. However, SQL queries are more interesting when used interactively. So, there's also a "script" version called SparkSQL8-script.scala, which we'll look at instead. (There are minor differences in how output is handled.)

The codez:

import util.Verse

import org.apache.spark.sql.DataFrameThe helper class Verse will be used to define the schema for Bible verses. Note the new imports.

Next, define the input path:

val inputRoot = "."

val inputPath = s"$inputRoot/data/kjvdat.txt"For HDFS, inputRoot would be something like hdfs://my_name_node_server:8020.

We discussed earlier that our console setup automatically instantiates the SparkSession as a variable named spark and it extracts the SQLContext variable it holds. It also does some convenient imports.

Next, after defining a few simple variables, we define a regex to parse the input verses and extract the book abbreviation, chapter number, verse number, and text. The fields are separated by "|", and also removes the trailing "~" unique to this file. Then it invokes flatMap over the file lines (each considered a record) to extract each "good" lines and convert them into a Verse instances. Verse is defined in the util package. If a line is bad, a log message is written and an empty sequence is returned. Using flatMap and sequences means we'll effectively remove the bad lines.

We use flatMap over the results so that lines that fail to parse are essentially put into empty lists that will be ignored.

val lineRE = """^\s*([^|]+)\s*\|\s*([\d]+)\s*\|\s*([\d]+)\s*\|\s*(.*)~?\s*$""".r

val versesRDD = sc.textFile(argz("input-path")).flatMap {

case lineRE(book, chapter, verse, text) =>

Seq(Verse(book, chapter.toInt, verse.toInt, text))

case line =>

Console.err.println("Unexpected line: $line")

Seq.empty[Verse] // Will be eliminated by flattening.

}Create a DataFrame from the RDD. Then, so we can write SQL queries against it, register it as a temporary "table". As the name implies, this "table" only exists for the life of the process. (There is also an evolving facility for defining "permanent" tables.) Then we write queries and save the results back to the file system.

val verses = sqlContext.createDataFrame(versesRDD)

verses.registerTempTable("kjv_bible")

verses.cache()

// print the 1st 20 lines. Pass an integer argument to show a different number

// of lines:

verses.show()

verses.show(100)

import sqlContext.sql // for convenience

val godVerses = sql("SELECT * FROM kjv_bible WHERE text LIKE '%God%'")

println("The query plan:")

godVerses.queryExecution // Compare with godVerses.explain(true)

println("Number of verses that mention God: "+godVerses.count())

godVerses.show()Here is the same calculation using the DataFrame API:

val godVersesDF = verses.filter(verses("text").contains("God"))

println("The query plan:")

godVersesDF.queryExecution

println("Number of verses that mention God: "+godVersesDF.count())

godVersesDF.show()Note that the SQL dialect currently supported by the sql method is a subset of HiveSQL. For example, it doesn't permit column aliasing, e.g., COUNT(*) AS count. Nor does it appear to support WHERE clauses in some situations.

It turns out that the previous query generated a lot of partitions. Using "coalesce" here collapses all of them into 1 partition, which is preferred for such a small dataset. Lots of partitions isn't terrible in many contexts, but the following code compares counting with 200 (the default) vs. 1 partition:

val counts1 = counts.coalesce(1)

val nPartitions = counts.rdd.partitions.size

val nPartitions1 = counts1.rdd.partitions.size

println(s"counts.count (can take a while, # partitions = $nPartitions):")

println(s"result: ${counts.count}")

println(s"counts1.count (usually faster, # partitions = $nPartitions1):")

println(s"result: ${counts1.count}")The DataFrame version is quite simple:

val countsDF = verses.groupBy("book").count()

countsDF.show(100)

countsDF.countSo, how do we use this script in the spark-shell that comes with the Spark distribution?

First, use SBT to create a jar ("package") of all the utility code (as well as the full Spark jobs we've written):

sbt packageThe jar is found in target/scala-2.11. Now you can pass this jar to spark-shell:

$SPARK_HOME/bin/spark-shell \

--jars target/scala-2.11/spark-scala-tutorial_2.11-X.Y.Z.jar [arguments]To run this script locally, use the same spark-shell or the SBT console, then use the Scala interpreter's :load command to load the file and evaluate its contents:

scala> :load src/main/scala/sparktutorial/SparkSQL8-script.scala

...

scala> :quit

>

To enter the statements using copy and paste, just paste them at the scala> prompt instead of loading the file.

SparkSQLFileFormats9-script.scala

This script demonstrates the methods for reading and writing files in the Parquet and JSON formats. It reads in the same data as in the previous example, writes it to new files in Parquet format, then reads it back in and runs queries on it. Then it repeats the exercise using JSON.

The key SparkSession and Dataset methods are SparkSession.read.parquet(inpath) and Dataset.write.save(outpath) for reading and writing Parquet, and SparkSession.read.json(inpath) and Dataset.write.json(outpath) for reading and writing JSON. (The format for the first write.save method can be overridden to default to a different format.)

See the script for more details. Run it the same way we ran SparkSQL8-script.scala.

This example shows the original implementation of streaming in Spark, the Spark streaming capability that is based on the RDD API. We construct a simple "word count" server. The example has two running configurations, reflecting the basic input sources supported by Spark Streaming.

The newer streaming module is called Structured Streaming. It is based on the Dataset API, for better performance and convenience. It has supports much lower-latency processing. Examples of this API are TBD here, but see the Apache Spark Structured Streaming Programming Guide for more information.

In the first configuration, which is also the default behavior for this example, new data is read from files that appear in a directory. This approach supports a workflow where new files are written to a landing directory and Spark Streaming is used to detect them, ingest them, and process the data.

Note that Spark Streaming does not use the _SUCCESS marker file we mentioned in an earlier notebook for batch processing, in part because that mechanism can only be used once all files are written to the directory. Hence, Spark can't know when writing the file has actually completed. This means you should only use this ingestion mechanism with files that "appear instantly" in the directory, i.e., through renaming from another location in the file system.

The second basic configuration reads data from a socket. Spark Streaming also comes with connectors for other data sources, such as Apache Kafka and Twitter streams. We don't explore those here.

SparkStreaming10 uses directory watching by default. A temporary directory is created and a second process writes the user-specified data file(s) (default: Enron emails) to a temporary directory every second. SparkStreaming10 does Word Count on the data. Hence, the data would eventually repeat, but for convenience, we also stop after 200 iterations (the number of email files).

The socket option works similarly, but this time, the data are written to a socket.

In either configuration, we need a second process or dedicated thread to either write new files to the watch directory or over the socket. To support this, SparkStreaming10Main.scala is the actual driver program we'll run. It uses two helper classes, util.streaming.DataDirectoryServer.scala and util.streaming.DataSocketServer.scala, respectively. It runs their logic in a separate thread, although each can also be run as a separate executable. Command line options specify which one to use and it defaults to DataSocketServer.

So, let's run this configuration first. In SBT, run SparkStreaming10Main (not SparkStreaming10MainSocket) as we've done for the other exercises.

There two SBT aliases, ex10directory, for watching a directory, and ex10socket, for listening on a socket.

This driver uses DataDrectoryServer or DataSocketServer to periodically write the data to a temporary directory, tmp/streaming-input, or to a socket, respectively.

If you watch the console output, you'll see messages like this:

-------------------------------------------

Time: 1413724627000 ms

-------------------------------------------

(limitless,2)

(grand,2)

(someone,4)

(priority,2)

(goals,1)

(ll,5)

(agree,1)

(offer,2)

(yahoo,3)

(ebook,3)

...The time stamp will increment by 2000 ms each time, because we're running with 2-second batch intervals. This particular output comes from the print method in the program (discussed below), which is a useful debug tool for seeing the first 10 or so values in the current batch RDD.

At the same time, you'll see new directories appear in output, one per batch. They are named like output/wc-streaming-1413724628000.out, again with a timestamp appended to our default output argument output/wc-streaming. Each of these will contain the usual _SUCCESS and part-0000N files, one for each core that the job can get!

Now let's run with socket input. In SBT, run SparkStreaming10MainSocket. The corresponding alias is ex8socket. In either case, this is equivalent to passing the extra option --socket localhost:9900 to SparkStreaming10Main, telling it spawn a thread running an instance of DataSocketServer to write data to a socket at this address. SparkStreaming10 will read this socket. the same data file (KJV text by default) will be written over and over again to this socket.

The console output and the directory output should be very similar to the output of the previous run.

SparkStreaming10 supports the following command-line options:

runMain SparkStreaming10 [ -h | --help] \

[-i | --in | --inpath input] \

[-s | --socket server:port] \

[--term | --terminate N] \

[-q | --quiet]Where the default is --inpath tmp/wc-streaming. This is the directory that will be watched for data, which DataDirectoryserver will populate. However, the --inpath argument is ignored if the --socket argument is given.

By default, it runs for 30 seconds, unless a different duration is specified with the "--terminate seconds" option. Pass 0 for no termination.

Note that there's no argument for the data file. That's an extra option supported by SparkStreaming10Main (SparkStreaming10 is agnostic to the source!):

-d | --data fileThe default is data/kjvdat.txt.

There is also an alternative to SparkStreaming10 called SparkStreaming10SQL, which uses a SQL query rather than the RDD API to do the calculation. To use this variant, pass the --sql argument when you invoke either version of SparkStreaming10Main or SparkStreaming10MainSocket.

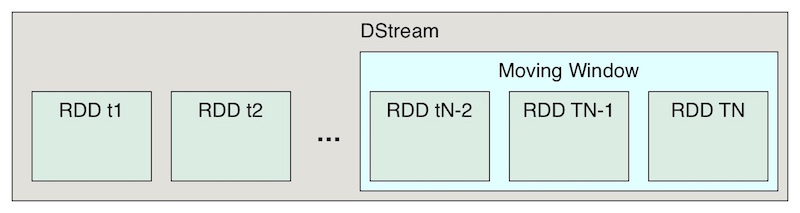

Spark Streaming uses a clever hack; it runs more or less the same Spark API (or code that at least looks conceptually the same) on deltas of data, say all the events received within one-second intervals (which is what we used here). Deltas of one second to several minutes are most common. Each delta of events is stored in its own RDD encapsulated in a DStream ("Discretized Stream").

You can also define a moving window over one or more batches, for example if you want to compute running statistics.

A StreamingContext is used to wrap the normal SparkContext, too.

Note: The new Structured Streaming module has a brand new runtime engine, providing true streaming capabilities.

Here are the key parts of the code for SparkStreaming10.scala:

...

case class EndOfStreamListener(sc: StreamingContext) extends StreamingListener {

override def onReceiverError(error: StreamingListenerReceiverError):Unit = {

out.println(s"Receiver Error: $error. Stopping...")

sc.stop()

}

override def onReceiverStopped(stopped: StreamingListenerReceiverStopped):Unit = {

out.println(s"Receiver Stopped: $stopped. Stopping...")

sc.stop()

}

}The EndOfStreamListener will be used to detect when a socket connection drops. It will start the exit process. Note that it is not triggered when the end of file is reached while reading directories of files. In this case, we have to rely on the 5-second timeout to quit.

...

val name = "Spark Streaming (10)"

val spark = SparkSession.builder.

master(master).

appName(name).

config("spark.app.id", name). // To silence Metrics warning.

config("spark.files.overwrite", "true").

// If you need more memory:

// config("spark.executor.memory", "1g").

getOrCreate()

val sc = spark.sparkContext

val ssc = new StreamingContext(sc, Seconds(batchSeconds))

ssc.addStreamingListener(new EndOfStreamListener(ssc))It is necessary to use at least 2 cores here, because each stream Reader will lock a core. We have run stream for input and hence one Reader, plus another core for the rest of our processing. So, we use * to let it use as many cores as it can, setMaster("local[*]")

With the SparkContext, we create a StreamingContext, where we also specify the time interval, 2 seconds. The best choice will depend on the data rate, how soon the events need processing, etc. Then, we add a listener for socket drops:

If a socket connection wasn't specified, then use the input-path to read from one or more files (the default case). Otherwise use a socket. An InputDStream is returned in either case as lines. The two methods useDirectory and useSocket are listed below.

try {

val lines =

if (argz("socket") == "") useDirectory(ssc, argz("input-path"))

else useSocket(ssc, argz("socket"))The lines value is a DStream (Discretized Stream) that encapsulates the logic for listening to a socket or watching for new files in a directory. At each batch interval (2 seconds in our case), an RDD will be generated to hold the events received in that interval. For low data rates, an RDD could be empty.

Now we implement an incremental word count:

val words = lines.flatMap(line => line.split("""[^\p{IsAlphabetic}]+"""))

val pairs = words.map(word => (word, 1))

val wordCounts = pairs.transform(rdd => rdd.reduceByKey(_ + _))

wordCounts.print() // print a few counts...

// Generates a new, timestamped directory for each batch interval.

if (!quiet) println(s"Writing output to: $out")

wordCounts.saveAsTextFiles(out, "out")

ssc.start()

if (term > 0) ssc.awaitTermination(term * 1000)

else ssc.awaitTermination()

} finally {

// Having the ssc.stop here is only needed when we use the timeout.

out.println("+++++++++++++ Stopping! +++++++++++++")

ssc.stop()

}This works much like our previous word count logic, except for the use of transform, a DStream method for transforming the RDDs into new RDDs. In this case, we are performing "mini-word counts", within each RDD, but not across the whole DStream.

The DStream also provides the ability to do window operations, e.g., a moving average over the last N intervals.

Lastly, we wait for termination. The term value is the number of seconds to run before terminating. The default value is 30 seconds, but the user can specify a value of 0 to mean no termination.

The code ends with useSocket and useDirectory:

private def useSocket(sc: StreamingContext, serverPort: String): DStream[String] = {

try {

// Pattern match to extract the 0th, 1st array elements after the split.

val Array(server, port) = serverPort.split(":")

out.println(s"Connecting to $server:$port...")

sc.socketTextStream(server, port.toInt)

} catch {

case th: Throwable =>

sc.stop()

throw new RuntimeException(

s"Failed to initialize host:port socket with host:port string '$serverPort':",

th)

}

}

// Hadoop text file compatible.

private def useDirectory(sc: StreamingContext, dirName: String): DStream[String] = {

out.println(s"Reading 'events' from directory $dirName")

sc.textFileStream(dirName)

}

}See also SparkStreaming10Main.scala, the main driver, and the helper classes for feeding data to the example, DataDirectoryServer.scala and

DataSocketServer.scala.

This is just the tip of the iceberg for Streaming. See the Streaming Programming Guide and the newer Structured Streaming Programming Guide for more information.

That's it for the examples and exercises based on them. Let's wrap up with a few tips and suggestions for further information.

Let's end with a tip; how to write "safe" closures. When you use a closure (anonymous function), Spark will serialize it and send it around the cluster. This means that any captured variables must be serializable.

A common mistake is to capture a field in an object, which forces the whole object to be serialized. Sometimes it can't be. Consider this example adapted from this presentation.

class RDDApp {

val factor = 3.14159

val log = new Log(...)

def multiply(rdd: RDD[Int]) = {

rdd.map(x => x * factor).reduce(...)

}

}The closure passed to map captures the field factor in the instance of RDDApp. However, the JVM must serialize the whole object, and a NotSerializableException will result when it attempts to serialize log.

Here is the work around; assign factor to a local field:

class RDDApp {

val factor = 3.14159

val log = new Log(...)

def multiply(rdd: RDD[Int]) = {

val factor2 = factor

rdd.map(x => x * factor2).reduce(...)

}

}Now, only factor2 must be serialized.

This is a general issue for distributed programs written for the JVM. A future version of Scala may introduce a "serialization-safe" mechanism for defining closures for this purpose.

See the README for a list of resources for more information.

Thank you for working through this tutorial. Feedback and pull requests are welcome.