Swift for TensorFlow provides a define-by-run programming model while also providing the full benefit of graphs. This is possible because of a core "graph program extraction" algorithm that we’ve built into the Swift compiler that takes imperative Swift code and automatically builds a graph as part of the normal compilation flow. This document frames and motivates the challenge, explains related work, describes our technique at a high level to contrast with prior work, explains an inductive mental model for how our approach works, and explains the resultant programming model in user terms.

It is helpful to have an idea of how the overall design of Swift for TensorFlow works, which you can get from the Swift for TensorFlow design overview document.

Our goal is to provide the best possible user experience for machine learning researchers, developers and production engineers. We believe that improving the usability of high performance accelerators will enable even faster breakthroughs in ML than is happening now.

Usability is not a simple thing: many aspects of a design contribute to (or harm) overall usability, and one of the key reasons ML frameworks exist in the first place is to provide usable access to high performance computation. After all, high theoretical performance is irrelevant when underutilized in practice, for example because it requires too much work or expertise from the programmer. As such, a primary goal of ours is to eliminate the compromises that have historically forced developers to choose between performance or usability.

Our approach came when we looked at the entire software stack from first principles, and concluded that we could achieve new things if we could enhance the compiler and language. The result of this is the compiler-based graph program extraction algorithm described in this document: it allows an ML programmer to write simple imperative code using normal control flow, and have the compiler do the job of building a TensorFlow graph. In addition to the performance benefits of graph abstractions, this framework allows other compiler analysis to automatically detect bugs (like shape mismatches) in user code without even running it.

There are several different approaches used by machine learning frameworks which we briefly explore here. Before we do that though, it is important to observe a key commonality about all of these approaches (including ours). Machine learning models contain a mix of two different kinds of code: tensor number crunching logic, and other general code for command line option processing, data pipeline setup, and other orchestration logic.

All of these approaches are just different ways for the system to "find" the tensor logic, extract it out, and send it to an accelerator. By exploring the diversity of approaches, we can see each of their strengths and also the tradeoffs forced by them.

Before modern ML frameworks were developed, linear algebra libraries like NumPy, Eigen and systems like MatLab were the primary way to explore ML techniques. These have the advantage that they are extremely concrete and familiar to programmers everywhere that understand a bit of linear algebra, they are relatively easy to debug and work with, and they work well with autodiff APIs such as autograd. This is one reason why popular introductions to neural networks teach neural nets this way.

Despite these strengths, few people use NumPy directly for computation-intensive ML research anymore: while it is relatively efficient on a single CPU, it doesn’t allow op fusion, doesn’t support GPUs (though extensions exist) or other exotic accelerators and doesn’t support distribution to multiple devices. This leads to orders-of-magnitude performance deltas, which prevents working with large models and large data.

These limitations led to the development of specialized frameworks like TensorFlow.

Perhaps the most popular solution to these challenges is to introduce a graph abstraction and introduce APIs for building and executing that graph (e.g. the TensorFlow session API). Many important performance optimizations become possible once the computation is expressed as a graph, as does support for accelerator hardware like GPUs and Cloud TPUs, and distribution across multiple accelerators.

The downside to this approach is that significant usability is sacrificed to achieve these goals. For example, as a user, dynamic control flow is difficult to express, because you have to use special looping/conditional operators and get control dependence edges right. Shape mismatch errors in your code are another pain point: typically they produce a stack trace through a bunch of runtime code you didn’t write, making it difficult to understand the bug and the ultimate fix. It is also awkward to work with tensors progressively in an interpreter, difficult to step through your code in the debugger, etc.

When confronted with these usability tradeoffs, some users choose to sacrifice a little bit of performance to get a significant improvement in usability.

Define-by-run approaches provide a "direct execution" model for machine learning operations, and the most widely used implementation is through an interpreter (as in TensorFlow with eager execution). Instead of building a graph when you say "matmul", they immediately execute a matmul operation on a connected device. This can be a big usability win, particularly for models that use control flow (because you can use Python control flow directly instead of staging control flow into a graph), dynamic models are much easier to write because you can mix in arbitrary Python code inline with your model, you can step through your model in a debugger, and you can iteratively design ML code right in the Python interpreter.

This approach has a lot of advantages, however there are also limitations of this approach:

- The low performance of the Python interpreter can matter for some kinds of models - particularly ones that use fine grained operations.

- The GIL can force complicated workarounds (e.g. mixing in C++ code) for models that want to harness multicore CPUs as part of their work.

- Even if we had an infinitely fast interpreter without a GIL, interpreters cannot "look ahead" beyond the current op. This prevents discovering future work that is dependent on work that it is currently dispatching and waiting for. This in turn prevents certain optimizations, like general op fusion, model parallelism, etc.

Finally, while automatic differentiation (AD) is not the focus of this whitepaper, define-by-run approaches prevent the use of "Source Code Transformation" techniques to AD. The "operator overloading" approaches they use are effective, but lose the ability to translate control flow constructs in the host language to the computation graph, make it difficult to perform optimizations or provide good error messages when differentiation fails.

Several active research projects are exploring the use of tracing JIT compilers in define-by-run systems (e.g. JAX, a new PyTorch JIT, etc). Instead of having the interpreter immediately execute an op, these approaches buffer up "traces" which provide some of the advantages of graph techniques with some of the usability advantages of the interpreter approach. On the other hand, tracing JITs introduce their own tradeoffs:

- Tracing JITs change the user model from computing tensor values back to building staged graph nodes, which is an observable part of the user model. For example, failures can come out of the runtime system when the trace is compiled/executed instead of at the op that is the source of the problem. This reduces the key usability advantages of define-by-run systems.

- Tracing JITs fully "unroll" computations, which can lead to very large traces.

- Tracing JIT are unable to "look ahead" across data dependent branches, which can lead to short traces in certain types of models, and bubbles in the execution pipeline.

- Tracing JITs allow dynamic models to intermix non-Tensor Python computation, but doing so reintroduces the performance problems of Python: values produced by such computation split traces, can introduce execution bubbles, and delay trace execution.

Overall, these approaches provide a hybrid model that provide much of the performance of graphs along with some of the usability of the interpreter-based define-by-run models, but include compromises along both axes.

Lightweight Modular Staging is a runtime code generation approach that allows expression of the generated code directly in the language. This approach is not widely used in the machine learning community, but newer research systems like DLVM are pioneering applications of LMS techniques to machine learning frameworks in Swift.

LMS allows direct expression of imperative tensor code within the source language, implicitly builds a graph at runtime, and requires no compiler or programming language extensions. On the other hand, while LMS techniques can be applied within many different languages, natural staging of control flow requires exotic features that are only supported by a few languages (e.g. scala-virtualized) because static analysis over the program structure is required. Furthermore, LMS is a user-visible part of the programming model - even in Scala, users are required to explicitly wrap the Rep type around data types.

LMS has the most similarities to our Graph Program Extraction approach. We chose to go with first-class compiler and language integration because "staging" of tensor computation is only one of the usability problems we are looking to solve. We are also interested in using compiler analysis to detect shape errors and other bugs at compile time, and we believe that the usability benefits of a fully integrated approach more than justify a modest investment into the compiler.

Our approach is based on the observation that a compiler can "see" all of the tensor operations in a program simply by parsing the code and applying static analysis techniques. This allows the user to program directly against a natural Tensor API and build additional high-level APIs (like layers and estimators) on top of tensors. The compiler then builds a TensorFlow graph as part of the standard compilation process, just like any other code generation task.

This provides a number of advantages, including:

- a natural define-by-run model, including the ability to use language control flow like

forloops andifstatements - the full performance of graphs

- full access to anything you can express in those graphs, including input pipeline abstractions

- natural interoperability between accelerated tensor operations and arbitrary non-tensor host code, copying data back and forth only when required by the user’s program

- the ability to produce compiler warning or error messages, which allows the programmer to avoid unnecessary host/device copies if desired and understand where they occur

- the ability to perform additional value-add static analysis in order to find other bugs and problems - e.g. to detect shape errors at compile time

There is a final point that is worth emphasis: while TensorFlow is the critical motivator for this project, these algorithms are completely TensorFlow independent. The same compiler transformations can be used to extract any computation that executes asynchronously with the host program while (optionally) communicating through sends and receives. This is useful for anything that represents computation as a graph, including other ML frameworks, other kinds of accelerators (e.g. for cryptography or graphics), and for graph-based distributed system programming models. These applications would also benefit from the Swift type system, e.g. the ability to statically diagnose invalid graphs at compile time.

Our goal is to provide a simple, predictable, and reliable programming model that is easy to intuitively understand, can be explained to a user in a few paragraphs, and which the compiler can reinforce with warnings and other diagnostics.

The most significant challenge is that the programming model must be amenable to reliable static analysis, but also allow the use of high-level user-defined abstractions like (layers and estimators). Our approach can be implemented in a few languages that support reliable static analysis. For a detailed discussion of the issues involved, please see our Why Swift for TensorFlow? document.

In order to explain our model, we provide a bottom-up intuitive explanation that starts from a trivial (and not very useful!) programming model, and incrementally builds it up to something that achieves our goals.

The output of our Graph Program Extraction algorithm is a domain-specific (e.g. TensorFlow) graph but the representation in Swift and the extraction algorithm is independent of most of those details.

We assume that each node has an operation name encoded as a string, dataflow inputs and results, may optionally have constant attributes, and could also potentially have side effects. Because the extraction algorithm doesn’t itself care about attributes or side effects, we ignore them in the discussion below and just consider the operation name and its dataflow inputs and results. We also assume that the graph has some ability to represent control flow, but the algorithms below are independent of those representation details. A subset of our approach can be used for graph abstractions that do not support control flow.

Though we use Swift and TensorFlow in the examples below, the algorithms are independent of them, and we would love to see others take this work and apply it to new domains and languages!

Reliable static-analysis-based graph extraction is trivial if you constrain the problem enough: to start with, we won’t support any mutation, pointer aliasing, control flow, function calls (or other abstractions!), aggregate values like structs or arrays, and no interoperability with host code.

With those restrictions, we are only able to express a very simple programming model where each "op" has magic syntax that takes an operation name, one or more graph values as arguments, and returns one or more result values. Because there is no interoperability with host code yet, the graph operations are only produced and consumed by graph operations.

Our implementation uses #tfop as a distinct syntax for spelling operations, and has well-known types (with names like TensorHandle and VariantHandle) to represent graph values. Note that TensorHandle is an internal implementation detail of our system, not something normal users would ever see or interact with. With this type and syntax for operations, we can write a function like this:

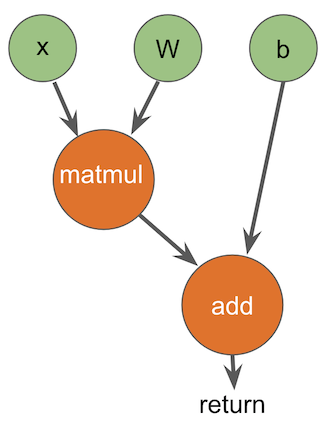

/// Compute matmul(x,w)+b in a TensorFlow graph.

func multiplyAndAdd(x: TensorHandle, w: TensorHandle, b: TensorHandle) -> TensorHandle {

let tmp = #tfop("MatMul", x, w)

let tmp2 = #tfop("Add", tmp, b)

return tmp2

}Because we added so many constraints on what we accept, it is trivial to transform this into a graph through static analysis: we can do a top-down walk over the code. Each function parameter is turned into an input to the graph. Each operation is trivial to identify, and can be transformed 1-1 into graph nodes: given a top-down walk, inputs are already graph nodes, and the op name, inputs, and any attributes (which aren’t discussed here) are immediately available. Because we have no control flow, there is exactly one return instruction, and it designates the result of the graph.

This gives us a result like this:

In addition to the translation process, it is important to notice that we have a well-defined language subset that is easy to explain to users (though, it is also not very useful yet!). The compiler is able to reinforce the limitations of our model through compiler errors, for example if the user attempted to store a TensorHandle in a variable, pass a TensorHandle to a non-graph operation like print, or use control flow. Because the analysis is built into the compiler, the compiler errors can point directly to the line of code that causes a problem, which is great for usability: the user knows exactly what they did wrong, and what they have to fix in order to get the code to compile.

That said, while this is a good foundation for a reliable, predictable, and implementable model, this design is so limited that it does not achieve our goals. To expand it, we start composing features on top to make the model more general and usable.

The next capability we will add are variables, which allow mutation and reassignment. For example, we want to allow code like this:

/// Compute a+b+c+d in a TensorFlow graph.

func addAll(a: TensorHandle, b: TensorHandle, c: TensorHandle, d: TensorHandle) -> TensorHandle {

var result = #tfop("Add", a, b)

result = #tfop("Add", result, c)

result = #tfop("Add", result, d)

return result

}Given that we have no control flow or aliasing, we can trivially eliminate all variable mutation from code by performing a top-down pass over the code, "renaming" the result of each assignment and updating later uses to use the renamed value. In this example, the compiler "desugars" this code into:

/// Compute a+b+c+d in a TensorFlow graph.

func addAll(a: TensorHandle, b: TensorHandle, c: TensorHandle, d: TensorHandle) -> TensorHandle {

let result1 = #tfop("Add", a, b)

let result2 = #tfop("Add", result1, c)

let result3 = #tfop("Add", result2, d)

return result3

}We don’t show a proof here, but it is well known that variables are provably lowerable to renamed immutable values - because our programming model doesn’t support aliasing or control flow. As described in the previous section, we also know that we can lower any of the resulting functions (that only use immutable values) into a graph. As such, by induction, we know that we can reliably lower this expanded class of functionality to a graph, while retaining our ability to reliably statically diagnose anything that exceeds our supported model.

This inductive model is the key to our transformation: we can introduce new abstractions, so long as we can provably eliminate them in a predictable way. Predictability is an essential requirement here: it would be problematic to introduce a new abstraction that requires a heuristic-based analysis technique to eliminate, because when that heuristic fails, it affects what sort of code can be compiled. The compiler would be able to diagnose that failure, but this would lead to a flaky and difficult-to-predict programming model for the user.

Early compilers were based on bit vector dataflow analysis and used renaming extensively in their optimizers to build more accurate use-def chains and eliminate false dependencies in their analyses. These techniques were eventually generalized into an approach known as Static Single Assignment (SSA) form which has been widely adopted by modern compiler systems.

The details of SSA form and its mathematical formulation are beyond the scope of this document, but will give the broad strokes. SSA generalizes the renaming transformation above to support static intraprocedural control flow (i.e., if, while, for, break, switch and other control flow statements) that is typically represented with a Control Flow Graph (CFG). Its standard formulation can rename variables that lack aliasing (which our model does not have), and introduces a concept called "phi" nodes to represent values at control flow merge points. This allows us to eliminate variable mutation from general control flow within a function for all standard language constructs. For example, SSA construction renames this code:

/// Compute a weird function in a TensorFlow graph using control flow and mutation.

func conditionalCode(a: TensorHandle, b: TensorHandle, c: TensorHandle, d: TensorHandle) -> TensorHandle {

var result = #tfop("Mul", a, b)

if ... {

result = #tfop("Add", result, c)

} else {

result = #tfop("Sub", result, d)

}

return result

}into this lowered pseudo code:

/// Compute a weird function in a TensorFlow graph using control flow and mutation.

func conditionalCode(a: TensorHandle, b: TensorHandle, c: TensorHandle, d: TensorHandle) -> TensorHandle {

bb0:

result1 = #tfop("Mul", a, b)

if (...) goto then_block else goto else_block

then_block:

result2 = #tfop("Add", result1, c)

goto after_ifelse

else_block:

result3 = #tfop("Sub", result1, d)

goto after_ifelse

after_ifelse:

result4 = phi(result2, result3)

return result4

}Once mutation is eliminated by SSA construction, we need to transform the control flow graph of the function into the control flow representation used by the graph we are targeting. In the case of TensorFlow, we choose to generate the pure-functional While and If control flow structures popularized by the XLA compiler backend but it would also be also be possible to generate standard TensorFlow Switch/Merge primitives.

Because we are lowering to a functional control flow representation, we use well known "Structural Analysis" techniques to transform a control flow graph into a series of Single-Entry-Single-Exit (SESE) regions. These techniques also work for arbitrary control flow graph structures, including irreducible control flow which can occur in languages that have unstructured goto statements (but Swift doesn’t).

When applied to the example above, our SESE transformation produces a structure like this:

/// Compute a weird function in a TensorFlow graph using control flow and mutation.

func conditionalCode(a: TensorHandle, b: TensorHandle, c: TensorHandle, d: TensorHandle) -> TensorHandle {

let result1 = #tfop("Mul", a, b)

// Note: named parameter labels are our representation for constant attributes.

let result4 = #tfop("If", ..., result1, c, d, true: ifTrueFunction, false: ifFalseFunction)

return result4

}

func ifTrueFunction(result1: TensorHandle, c: TensorHandle, d: TensorHandle) -> TensorHandle {

let result2 = #tfop("Add", result1, c)

return result2

}

func ifFalseFunction(result1: TensorHandle, c: TensorHandle, d: TensorHandle) -> TensorHandle {

let result3 = #tfop("Sub", result1, d)

return result3

}Our implementation handles the branching constructs and loops that Swift supports, and it should be straightforward to generalize them to support exotic control flow constructs like indirect gotos, so long as the target graph has a way of expressing this, or the host program has a way to asynchronously communicate destination identifiers to the graph runtime.

Combined, SSA construction and SESE region formation reliably desugars arbitrary local mutation and local control flow into the form we know we can lower to a graph, which is an important expansion of our programming model. That said, there are still important missing pieces to our model, so let’s keep building!

Beyond the ability to use language native control flow, perhaps the biggest payoffs of the define-by-run model is that they allow users to mix and match tensor computation with host code: this is critical for dynamic machine learning models (common in NLP), for reinforcement learning algorithms that include simulators, because researchers sometimes want to implement their own Tensor ops without writing CUDA code, and because it is nice to be able to just call print to see what your code is doing!

Before we explain our approach, we’ll introduce an (abstracted) example that uses an Atari simulator in the middle of a training loop, and explain how different define-by-run approaches handle it. The example is written in our current limited programming model, but with the addition of host-to-graph communication:

func hostAndGraphCommunication() -> TensorHandle {

var values = #tfop("RandomInitOp")

for i in 0 ... 1000 {

let x = #tfop("SomeOp", values)

// This is not a tensor op, it has to run on the host CPU.

// It might be dispatched to a cluster of worker machines.

let result = atariGameSimulator(x)

let y = #tfop("AnotherOp", x)

values = #tfop("MixOp", result, y)

}

return result

}In interpreter-based define-by-run systems, the host CPU is running the interpreter, and it dispatches every operation when it encounters them. When it encounters the atariGameSimulator call (which isn’t a TensorFlow op), the interpreter just copies the data back from the accelerator to the host, makes the call, and copy the result back to the accelerator when it gets to the MixOp operation that uses it.

Tracing JITs take this further by having the interpreter collect longer series of tensor operations - this "trace" of operations allows more optimization of the tensor code. This example is too simple to really show the power of this, but even here a tracing JIT should be able to build a trace that includes both the RandomInitOp operation and the SomeOp operation on the first iteration, allowing inter-op fusion between them. On the other hand, tracing JITs are forced to end a trace any time a data dependency is found: the call to atariGameSimulator needs the value of x, so the trace stops there.

Because of the way these systems work, neither of them can discover that AnotherOp can be run on the accelerator in parallel with atariGameSimulator on the host. Furthermore, because a tracing JIT splits the trace, data layout optimizations between SomeOp and AnotherOp are not generally possible: the two are in separate traces.

This sort of situation is just one example of where the compiler-based approach can really shine, because the compiler can see beyond the call to atariGameSimulator. This gives it better scope of optimization, can allow it to build much larger regions, and perform copies to the host at the exact points where the model requires it. This capabilities are particularly important when aiming to get full utilization of ultra high performance accelerators like Cloud TPUs.

Host/device communication with Graph Program Extraction

TensorFlow already has advanced primitives to send and receive data between devices, and we can actually represent the entire training loop as a single graph. As such, in the face of host/device communication, our compiler "partitions" the input into two different programs: one that runs on the host, and one that is run by TensorFlow (represented as a graph). The algorithm to do this isn’t trivial, but it is easy to conceptually understand, particularly given the limitations in our programming model at this point: there are no abstractions in the way like function calls or user defined data types.

First we start by duplicating the function, and replace all host code with send and receive ops. This gives us code like this:

func hostAndGraphCommunication_ForGraph() -> TensorHandle {

var values = #tfop("RandomInitOp")

for i in 0 ... 1000 {

let x = #tfop("SomeOp", values)

// REMOVED: let result = atariGameSimulator(x)

#tfop("SendToHost", x)

let result = #tfop("ReceiveFromHost")

let y = #tfop("AnotherOp", x)

values = #tfop("MixOp", result, y)

}

return result

}We know that this transformation provably eliminates all host-only code, so we can now progressively desugar and generate a graph using our earlier method. Because the graph captures all of the tensor computation, it is straightforward for TensorFlow’s graph runtime to perform the optimizations that tracing JITs achieve. Additional optimizations also fall out of this approach, e.g. executing AnotherOp in parallel with the host computation and layout optimizations between SomeOp and AnotherOp.

With the graph built, the compiler next needs to attend to the code that runs on the host. It simply removes the tensor operations, and replace them with calls into the TensorFlow runtime. It also inserts calls into the runtime to start and finish execution of the TensorFlow graph (which roughly correspond to Session.run).

Altogether, we get host code like this:

func hostAndGraphCommunication() -> TensorHandle {

let tensorProgram = startTensorFlowGraph("... proto buf for TensorFlow graph ... ")

// REMOVED: var values = #tfop("RandomInitOp")

for i in 0 ... 1000 {

// REMOVED: let x = #tfop("SomeOp", values)

let x = receiveFromTensorFlow(tensorProgram)

// This is not a tensor op, it has to run on the host CPU.

// It might be dispatched to a cluster of worker machines.

let result = atariGameSimulator(x)

sendToTensorFlow(tensorProgram, result)

// REMOVED: let y = #tfop("AnotherOp", x)

// REMOVED: values = #tfop("MixOp", result, y)

}

let result = finishTensorFlowGraph(tensorProgram)

return result

}The result of these transformations is that we get two co-executing programs running on different devices, and that these devices only have to rendezvous with each other when they need to exchange data. This directly reflects the hardware design of high-performance accelerators: they are independent processors that run code asynchronously from the main CPU. At the physical level, they communicate by sending and receiving messages - e.g. with DMA transfers or network packets.

Because we produce a TensorFlow graph, this design allows TensorFlow to apply interesting heterogenous techniques. For example, TensorFlow’s XLA compiler for GPUs applies aggressive fusion between operations, but allows the CPU to drive the top level control flow (like the training loop). All of this naturally falls out of this approach.

One final comment: this sort of transformation is well known in the compiler world as program slicing. Though we are not aware of these techniques being used for this purpose, the algorithms and theory behind these techniques have been well studied for many years.

Control flow synchronization with Graph Program Extraction

We’ve glossed over some important topics in the discussion above: How do the two co-executing programs stay synchronized with each other? Why do both programs duplicate the for i in 0 ... 1000 computation? What happens if the loop condition is something that can only run on the host? If we do something non-deterministic (like a random number generator) do the two programs diverge?

Let’s consider a simple example which does computation iteratively until a key is pressed on the user’s keyboard - a predicate that clearly has to be evaluated on the host. To make later code easier to explain, the example uses while true and break, but the compiler can handle any form:

func countUntilKeyPressed() -> TensorHandle {

var result = #tfop("Zero")

while true {

let stop = keyPressed()

if stop { break }

result = #tfop("HeavyDutyComputation", result)

}

return result

}When we apply the program slicing algorithm above, we apply program slicing to partition the tensor operations out to a graph. While doing so, the algorithm notices that the HeavyDutyComputation is "control dependent" on the condition that exits the loop: you can’t move the loop over without moving over control flow that could cause the loop to exit. When doing this, it sees that keyPressed() is a host function (just like atariGameSimulator call in the previous example) and so it arranges to run the function on the host and send the value over to TensorFlow. The graph function ends up looking like this:

func countUntilKeyPressed_ForGraph() -> TensorHandle {

var result = #tfop("Zero")

while true {

// REMOVED: let stop = keyPressed()

let stop = #tfop("ReceiveFromHost")

if stop { break }

result = #tfop("HeavyDutyComputation", result)

}

return result

}... and the host function looks like this:

func countUntilKeyPressed() -> TensorHandle {

let tensorProgram = startTensorFlowGraph("... proto buf for TensorFlow graph ... ")

// REMOVED: var result = #tfop("Zero")

while true {

let stop = keyPressed()

sendToTensorFlow(tensorProgram, stop)

if stop { break }

// REMOVED: result = #tfop("HeavyDutyComputation", result)

}

let result = finishTensorFlowGraph(tensorProgram)

return result

}It is interesting to see how the host is simply shadowing the heavy duty computation that the accelerator is performing, sending over a stream of boolean values that tells the accelerator when to stop. At the end of the computation, the tensor result value is copied back one time as the result of the program.

Having the host CPU handle all of the high level control flow in a machine model guarantees that the two programs stay synchronized: for example, non-deterministic random predicates are evaluated in one place (on the host) sending the result over to the accelerator. This is also a standard model for orchestrating GPU computation.

On the other hand, this approach can be a performance concern when the latency between the host and accelerator is high (e.g. if there is networking involved) or when seeking maximum performance from an accelerators like a Cloud TPU. Because of that, as a performance optimization, our compiler looks for opportunities to reduce communication by duplicating computation on both devices. This allows it to promote simple conditions (like for i in 0 ... 1000) to run "in graph", eliminating a few communication hops.

Performance predictability and implicit host/device communication

A final important topic is performance predictability. We like that our define-by-run model allows the user to flexibly intermix host and tensor code, but this brings in a concern that this could lead to very difficult to understand pitfalls, where large tensor values are bouncing back and forth between devices excessively.

The solution to this fits right into the standard compiler design: by default, Swift produces compiler warnings when an implicit copy is made (as in the examples above), which makes it immediately clear when a copy is being introduced.

These warnings can be annoying when the copies are intentional, so the user can either disable the warning entirely (e.g. when doing research on small problem sizes where performance doesn’t matter at all) or the warnings can be disabled on a case-by-case basis by calling a method (currently named x.toDevice() and x.toHost()) to tell the compiler (and future maintainers of the code!) that the copy is intentional.

This model is particularly helpful to production engineers who deploy code at scale, because they can upgrade the warning to an error, to make sure that no implicit copies creep in, even as the code continues to evolve.

Now that we have a robust approach for handling communication between the host program and the TensorFlow program, let’s return to the task of improving the programming model to something that is more user friendly and less primitive.

As we discussed before, we can add any abstractions to our model as long as we have a provable way to eliminate them. Once they are eliminated, we can lower the code to graph using the approaches described above. In the case of structs and tuples, Swift is guaranteed to be able to scalarize them away, so long as the compiler can see the type definition. This is possible because we have no aliasing in our programming model.

This is great because it allows users to compose high level abstractions out of tensors and other values. For example, the compiler scalarizes this code:

struct S {

var a, b: TensorHandle

var c: String

}

let value = S(a: t1, b: t2, c: "Hello World")

print(value.a)

let tuple = (t3, t4)

print(tuple.0)Into:

let valueA = t1, valueB = t2

let valueC = "Hello World"

print(valueA)

// equivalent to: tuple0 = y; tuple1 = z

let (tuple0, tuple1) = (y, z)

print(tuple0)This allows the compiler to handle the string processing logic on the host, and tensor processing in TensorFlow. The user can build their model in a way that feels most natural to them.

While structs and tuples can be handled as above, classes are more involved because their references may be aliased, among other reasons. We will discuss them in more detail below.

The next big jump is to add function calls, which the compiler can provably eliminate through inlining. The two requirements are that the compiler needs to be able to see the body of the function, and that the call must be a direct call: indirect function calls, virtual calls, and calls through existential values require something like alias or class hierarchy analysis to disambiguate, and heuristic based techniques like these lead to a fragile programming model.

Fortunately, Swift has a strong static side, and all top-level functions, methods on structs, and many other things (like computed properties on structs) are consistently direct calls. This is a huge step forward in terms of our modeling power, because we can now build a reasonable user-facing set of Tensor APIs. For example, something like this:

struct Tensor {

// TensorHandle is now an internal implementation detail, not user exposed!

private var value: TensorHandle

func matmul(_ b: Tensor) -> Tensor {

return Tensor(#tfop("MatMul", self.value, b.value))

}

static func +(lhs: Tensor, rhs: Tensor) -> Tensor {

return Tensor(#tfop("Add", lhs.value, rhs.value))

}

}

func calculate(a: Tensor, b: Tensor, c: Tensor) -> Tensor {

let result = a.matmul(b) + c

return result

}Desugars the body of the calculate function with inlining into:

let tmp = Tensor(#tfop("MatMul", a.value, b.value))

let result = Tensor(#tfop("Add", tmp.value, c.value))... and then scalarizes the Tensor structs to produce this:

let tmp_value = #tfop("MatMul", a_value, b_value)

let result_value = #tfop("Add", tmp_value, c_value)... which is trivially promotable to the graph. It is very nice how these simple desugaring transformations compose cleanly, but this is only the case if they are guaranteed and can be tied to simple language constructs that the user can understand.

We don’t have space to go into it here, but this inlining transformation also applies to higher-order functions like map and filter so long as their closure parameters are non-escaping (which is the default): inlining a call to map eventually exposes a direct call to its closure. Additionally, an important design point of Swift is that the non-aliasing property we depend on even extends to inout arguments and the self argument of mutating struct methods. This allows the compiler to aggressively analyze and transform these values, and is a result of Swift’s law of exclusivity which grants Fortran style non-aliasing properties to these values.

It is also worth mentioning that TensorFlow graphs support function calls. In theory we should be able to use them to avoid the code explosion problems that can theoretically come from extensive inlining. Very few machine learning models implemented with TensorFlow use these features so far and we haven’t run into graph size problems in practice, so it hasn’t been a priority to explore this.

The Swift generics model can be provably desugared using generics specialization - and of course, this is also an important performance optimization for normal Swift code! This is a huge expansion of the expressive capabilities of our system: it allows the rules around the dtype of Tensors to be captured and enforced directly by Swift. For example, we can expand our example above to look like this:

struct Tensor<Scalar : AccelerableByTensorFlow> {

private var value: TensorHandle

func matmul(b: Tensor) -> Tensor {

return Tensor(#tfop("MatMul", self.value, b.value))

}

static func +(lhs: Tensor, rhs: Tensor) -> Tensor {

return Tensor(#tfop("Add", lhs.value, rhs.value))

}

}The nice thing about this is that users of the Tensor API get dtype checking automatically: if you accidentally attempt to add a Tensor<Float> with a Tensor<Float16>, you’ll get a compile-time error, instead of a runtime error from TensorFlow. This happens even though the underlying TensorHandle abstraction is untyped.

Another nice thing about this is that this extends to high level and user-defined abstractions as well, e.g. if you define code like this:

struct DenseLayer<Scalar : Numeric> {

var weights: Tensor2D<Scalar>

var bias: Tensor1D<Scalar>

var dLoss_dB: Tensor1D<Scalar>

var dLoss_dW: Tensor2D<Scalar>

init(inputSize: Int, outputSize: Int) {...}

}

...

fcl = DenseLayer<Float>(inputSize: 28 * 28, outputSize: 10)Generic specialization will desugar into this:

struct DenseLayer_Float {

var weights: Tensor2D_Float

var bias: Tensor1D_Float

var dLoss_dB: Tensor1D_Float

var dLoss_dW: Tensor2D_Float

init(inputSize: Int, outputSize: Int) {...}

}

...

fcl = DenseLayer_Float(inputSize: 28 * 28, outputSize: 10)... and then Swift will apply all the other destructuring transformations until we get to something that can be trivially transformed into a graph.

There is a lot more to go here, but this document is already too long, so we’ll avoid going case by case any further. One last important honorable mention is that Swift’s approach to "Protocol-Oriented Programming" [youtube] allows many things traditionally expressed with OOP to be expressed in a purely static way through composition of structs using the mix-in behavior granted by default implementations of protocol requirements.

We’ve covered the static side of Swift extensively, but have completely neglected its dynamic side: classes, existentials, and dynamic data structures built upon them like dictionaries and arrays. These are actually two different classes to consider. Let’s start with the dynamic types first:

Swift puts aggregate types into two categories: dynamic (classes and existentials) and static (struct, enum, and tuple). Because existential types (i.e., values whose static type is a protocol) could be implemented by a class, here we just describe the issues with classes. Classes in Swift are extremely dynamic: each method is dynamically dispatched via a vtable (in the case of a Swift object) or a message send (with a type deriving from NSObject or another Objective-C class on Apple platforms only). Furthermore, properties in classes can be overridden by derived classes, and pointers to instances of classes can be aliased in an unstructured way.

As it turns out, this is the same sort of situation you get in object oriented languages like Java, C#, Scala, and Objective-C: in full generality, class references cannot be analyzed (this is discussed in our Why Swift for TensorFlow document). A compiler can handle many common situations through heuristic-based analysis (using techniques like interprocedural alias analysis and class hierarchy analysis) but relying on these techniques as part of the programming model means that small changes to code can break the heuristics they depend on. This is an inherent result of relying on Heroic optimizations as part of the user-visible behavior of the programming model.

Our feeling is that it isn’t acceptable to bake heuristics like these into the user-visible part of the programming model. The problem is that these approaches rely on global properties of a program under analysis, and small local changes can upset global properties. In our case, that means that a small change to an isolated module can cause new implicit data copies to be introduced in a completely unrelated part of the code - which could cause gigabytes worth of data transfer to be unexpectedly introduced. We refer to this as "spooky action at a distance", and because it could introduce unsettling feelings into our users, we deny it.

The second problem is that collections like Array, Dictionary, and other types are built out of reference types like classes. It turns out that Swift’s array and dictionary types are built on the principles of value semantics, which compose very naturally on top of the pointer aliasing and other existing analyses that Swift provides. Because these are very commonly used and could be special-cased in the implementation, one could argue that we should build special support for these types into the compiler (like tf.TensorArray in TensorFlow).

On the other hand, indices into these data structures are almost always dynamic themselves: you don’t use constant indices into an array, you use an array because you’re going to have a for loop over all its elements. While it is possible that we could build in special support for unrolling loops over array elements, this is a slippery slope which would eventually lead to a large number of additional special cases added to the model. At this point in our implementation, we prefer to hold the line and not special case any "well known" types: it is easier to add new things later if needed than it is to take add them proactively and take them away if unneeded.

While Swift’s type system overall is a good fit for what we’re doing in this project, there is one exceptional case that we’d love to see improved. Swift has a well designed error handling system (with a detailed rationale). Unfortunately, while the design of this system was specifically intended to support throwing typed errors, at present, Swift only supports throwing values through type-erased Error existentials. This makes error handling completely inaccessible to our TensorFlow work and anything else that relies on reliable static analysis. We would love to see this extended to support "typed throws" as a natural solution to complete the static side of Swift.

Above we claimed that good usability requires us to "provide a simple, predictable, and reliable programming model that is easy to intuitively understand, can be explained to a user in a few paragraphs, and which the compiler can reinforce with warnings and other diagnostics". We think that our design achieves that.

Our user model fits in a single paragraph: you write normal imperative Swift code against a normal Tensor API. You can use (or build) arbitrary high level abstractions without a performance hit, so long as you stick with the static side of Swift: tuples, structs, functions, non-escaping closures, generics, and the like. If you intermix tensor operations with host code, the compiler will generate copies back and forth. Likewise, you’re welcome to use classes, existentials, and other dynamic language features but they will cause copies to/from the host. When an implicit copy of tensor data happens, the compiler will remind you about it with a compiler warning.

One of the beauties of this user model is that directly aligns with several of the defaults encouraged by the Swift language (e.g. closures default to non-escaping and the use of zero-cost abstractions to build high level APIs), and the core values of Swift API design (e.g. the pervasive use of value semantics strongly encourages the use of structs over classes). We believe that this will make Swift for TensorFlow "feel nice in practice" because you don’t have to resort to anti-idiomatic design to get things to work.

Our implementation work is still early, but we are shifting from an early research project into a public open source project now because we believe that the theory behind this approach has been proven out. We are far enough along in the implementation to have a good understanding of the engineering concerns facing an actual implementation of these algorithms.