...menustart

- Hidden Markov Model

...menuend

Hidden Markov Model

This pacman can eat ghost but first he has to find them. So soon as pacman start moving , you will see in the bottom colord numbers , which are kind of noisy readings of how far the ghosts are.

Now let's say I want to eat the orange ghost. If you could somehow take these numbers over time and combine them with your model of how the world works -- means where are the walls, where are the maze -- and also your model of how the ghosts move , and figure out where they are.

- A Markov Model is a chain-structured Bayes' net (BN)

- Each node is identically distributed (stationarity)

- Value of X at a given time is called the state

- As a Bayes' net

- P(X₁)

- P(Xt | Xt-1)

- Parameters: called transition probability or dynamics, specify how the state evolves over time (also, initial state probabilities)

- this is the model how the world changes

- Same as MDP transition model , but no choice of action

- here is no action, you just watching

- Basic conditional independence:

- Past and future independent of the present

- the past anything before the current state and future anything beyond the current state are independent given the current state

- Each time step only depends on the previous

- This is called the (first order) Markov property

- Past and future independent of the present

- Note that the chain is just a (growable) BN

- We can always use generic BN reasoning on it if we truncate the chain at a fixed length

Hidden Markov Models

A Markov model can talk about how the world changes , but if I forecast into the future sooner or later I just don't know anything anymore.

But hidden Markov model says 2 things: I know how the world changes in a time step which let me figure out roughly what's gonna happen in the absense of evidence and at every time step I also getting some kind of reading -- I got some evidence that helps me sharpen my belief about what's happening. So as the same time that time passes ,evidence also comes in. The robot moves and takes another sonar reading.

- Markov chains not so useful for most agents

- need observations to update your beliefs

- Hidden Markov models (HMMs)

- Underlying Markov chain over states S

- You observe outpus (effects) at each time step

- As a Bayes' net :

- the hidden variable: where or not it's raining -- True or False

- the observed variable: an umbrella

So what do we need to define the HMM ?

- we need 1 function which says how rain on one day depends on the previous day.

- we also need a function says given rain and separately given sun, what's probability of seeing an umbrella

So from a single observation of an umbrella you don't know very much , but if day after day you're seeing the umbrella you start to kind of gain some confidence.

- An HMM is defined by:

- Initial distribution: P(X₁)

- Transitions: P(X|X₋₁)

- how the world evolved in a single time step

- Emissions: P(E|X)

- the probability of various evidence values given the underlying state , which we then used to predict the opposite -- something about x.

- P(X₁) = uniform

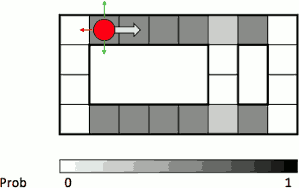

- P(X|X') = usually move clockwise, but sometimes move in a random direction or stay in place

- for that red square , it's 50% precent probability of moving right , 1/6 probability that you'll stand, 1/6 probability to go in other direction.

- Where do these conditional probabilities come from ?

- This is your assumptions about the world , you might learn them from data, for now that's just an input.

- That's what happens from that one state. But you generally don't know what state you're in, and you need to sum over all the options , that's the forward algorithm was about.

- P(Rᵢⱼ|X) = same sensor model as before: red means close, green means far away.

- somewhere there has to be specified precisely the probability of reading at a certain position given the underlying state.

- so it might say if you read at (3,3) and the ghost is there , your probability of getting red is 0.9. Those facts live in the emission model , they say how the evidence directly relates to the state at that time.

- HMMs have 2 import independence properties

- Markov hidden process: future depends on past via the present

- same as MM.

- Current observation independent of all else given current state

- given X₃ , E₃ is independent of all everything else X₃.

- Markov hidden process: future depends on past via the present

- Quiz: does this mean that evidence variables are guaranteed to be independent ?

- If I don't observe anything I could say : Is the evidence I see at time₁ independent of the evidence I see at time₂ ?

- It is like the umbrella on tuesday is independent of the umbrella on Wednesday.

- So It seems like it shouldn't be. The evidence variables are absolutely not independent. They're only conditionally independent.

The prior probability P(X₀), dynamics model P(Xt+1|Xt ), and sensor model P(Et|Xt) are as follows:

We perform a first dynamics update ,and fill in the resulting belief distribution B'(X₁)

| X₁ | B'(X₁) |

|---|---|

| 0 | 0.415 |

| 1 | 0.585 |

- 0.415 = 0.7*0.4+0.3*0.45

We incorporate the evidenc E₁=b. We fill in the evidence-weighted distribution P(E₁=b|X₁)·B'(X₁), and and the (normalized) belief distribution B(X₁).

For every HMM there is a hidden state -- which is usually the thing you want to figure out -- , and an evidence variable -- which is the thing you got to observe.

You get the evidence at every time and you usually want to figure out the state at every time.

-

Speech recognition HMMs:

- Observations are acoustic signals (continuous valued)

- States are specific positions in specific words (so, tens of thousands)

-

Machine translation HMMs:

- Observations are words (tens of thousands)

- States are translation options

-

Robot tracking:

- Observations are range readings (continuous)

- States are positions on a map (continuous)

Now we are going to talk about how to keep track of what you believe about a variable X -- the state variable -- as evidence comes it and time passes, and from this we'll build up the full-forward algorithm.

The task is to figure out at any given time what do I believe is happening in the hidden state ( Bt(X) ) given all the evidence from the first time step all the way up to the current time.

- Filtering, or monitoring, is the task of tracking the distribution Bt(X) = Pt(Xt | e₁, …, et) (the belief state) over time

- We start with B₁(X) in an initial setting, usually uniform

- As time passes, or we get observations, we update B(X)

- The Kalman filter was invented in the 60’s and first implemented as a method of trajectory estimation for the Apollo program

The robot doesn't know where it is . It knows the map -- somebody gave blueprints .

It is going down the corridor and all do is shoot out lasers in each direction and see how close they bounced off a wall.

- Sensor model: can read in which directions there is a wall, never more than 1 mistake

- Motion model: may not execute action with small prob.

So it knows there's a wall right here , but no wall in front of me. And if it gets a reading that says there's wall on my left and right but not in front or behind, then suddenly it shouldn't think it's anywhere in this building. Where should I think it is? It is kind of think it's in the corridors, corridors look like that. It's the sensor model , formly is conditioned on my current position, I need say a distribution over readings. Let's image that instead of the continuous readings , the readings are wall or not in each direction.

So if I sense that is a wall above and below I should have pretty high probability of my belief distribution of being in the dark gray squares. I should have some smaller probability of being in the lighter grey square.

- t=1

- Lighter grey: was possible to get the reading, but less likely b/c required 1 mistake

Time passes.

As I continue reading north and south walls , what will happen is there will be fewer and fewer places which are consistent with my history of readings.

Inference in Markov model is acutally the approximate inference .

Let's do the base cases. There's really 2 things that happen in HMMs.

One is time passes. You go from X at a certain time to X at the next time. The other thing happens you see evidence. There things are interleaved.

But if all you had was a single time slice, you had X₁ and you saw evidence at time₁ E₁ , and you want to compute what's probability over my hidden state X₁ given my evidence E₁. So you just want to compute this conditional probability : P(X₁|e₁).

- I know P(X₁) , this is what before I see the evidence.

- Now I also know a distribution that tells me how the evidence relates to X₁ : P( E₁ | X₁ ).

That's not quite what I want. What I want is P(X₁|e₁).

- X is capital because it's a vector here. I need one of these numbers for each value of X.

- e is lowercase because there's a specific value , it's scalar.

P(X₁|e₁) = P(X₁,e₁)/P(e₁)

= P(e₁|X₁)·P(X₁) /P(e₁)

The above manipulation I just did has nothing to do with HMMs. Now what I don't know is P(e₁). But that is a constant as I vary X (not understand!).

So as you saw with the variable elimination I can just ignore it. So the actual reasoning goes something a little bit more cpmpactly .

I'm instead going to compute P( X₁,e₁ ) and normalize in the end. I know how to compute it -- P(X₁,e₁) = P(e₁|X₁)·P(X₁). So I compute all of these products: current probability times evidence probability. And then once I have that whole vector of those I re-normalize and now I have the conditional distribution of P(X₁|e₁). That is what happens when you incorporate evidence: you take your current vector of probabilities P(X₁) ,you multiply each one by the appropriate evidence factor and then you renormalize it.

P(x₁|e₁) = P(x₁,e₁)/P(e₁)

∝ P(x₁,e₁)

= P(x₁)·P(e₁|x₁)

大家都无视 P(e₁) , 最后重新 normalize

The other base case is this.

You have a distribution over X₁ and rather than seeing evidence , time passes by one step. Well in this case I know P(X₁) , and I know P(X₂|X₁) . But I want is P(X₂).

全概率模型

- Those 2 pieces assembled to do everything you need in HMMs.

- Assume we have current belief P(X | evidence to date)

- B(Xt) = P(Xt|e1:t)

- Then, after one time step passes:

- Or, compactly :

- it says: you want to know the probability tomorrow of being at some particular Xt+1. You consider how likely it is to get to Xt+1 from each locations (X'). So you want to know how likely it is that I'll end up at this particular Xt+1 , you consider all the places that could get you there , in one time step. and you say : what's the probability of being , here at A and then moving there , what's the probability ? and whatelse if at B, C, ...

- that is this, you summer(∑) all of the places you could have been , you look how likely it is that you were there ( B(xt) ) to begin with , times how likely it is had you been there to get to X'.

- Basic idea: beliefs get “pushed” through the transitions

- With the “B” notation, we have to be careful about what time step t the belief is about, and what evidence it includes

- As time passes, uncertainty “accumulates”

- That's basically your robot knows what's going on today and sooner or later if you never get any more evidence , the robot will become more and more confused until it has no idea what's going on.

- Assume we have current belief P(X | previous evidence):

- B'(Xt+1) = P(Xt+1|e1:t)

- I have a belief vector that says here's my probability distribution over what's going on at a centain time BEFORE I see my evidence.

- Then , after the evidence tomorrow comes in:

- take you current vector which represents the various probabilities right now , for each probability multiply by the evidence factor. So if the evidence is totally inconsistent with that state then even if somthing had high probability suddenly it might get zero out if it can't produce the evidence.

- so you go to each probability of each state you multiply each one by the evidence.

- so the blue thing is your probability before you saw your evidence , you weighted by the evidence, and then this vector doesn't add to 1 anymore. So you re-normalized it now it adds up to 1 again , now the red thing is including the evidence you just saw.

- Or:

- Basic idea: beliefs “reweighted” by likelihood of evidence

- Unlike passage of time, we have to renormalize

- We are given evidence at each time and want to know

- Bt (X) = P(Xt|e1:t)

- We can derive the following updates:

- This is exactly variable elimination with order X₁,X₂,...

The forward algorithm is a dynamic program for computing at each time slice , the distribution over the state at that time given all the evidence to date.

- Every time step, we start with current P(X | evidence)

- We update for time:

- We update for evidence:

- The forward algorithm does both at once (and doesn’t normalize)

- model

- state X: cell in tiled map , eg.(2,3)

- transition model: P(X' | X )

- Pr( ghost is at position p at time t + 1 | ghost is at position oldPos at time t )

- probability of ghost move from state X to state X'

- sensor reading: noisyDistance

- estimated Manhattan distance to the ghost

- that is , how close ghost is

- emission model: P( noisyDistance | TrueDistance )

- Observation : got a sensor reading

- for each position p (it a state ) in all legal positions

- calculate pacman's manhattan distance to p state -- trueDistance

- newBelief[p] = self.beliefs[p] * emissionModel[trueDistance]

- eventually , re-normalize , and update self.beliefs

- newBelief.normalize()

- self.beliefs = newBelief

- for each position p (it a state ) in all legal positions

- Time Elapse: the ghost may move

- note: you don’t know exactly where is the ghost , you need compute the distribution , for all possible positions

- for each position oldPos (it a state ) in all legal positions

- you may get the distribution : newPostDist -- P( newPos | oldPos )

- then for every newPostion, you update the part of its new belief

- newBelief[ newPos ] += prob * self.beliefs[ oldPos ]

- Note !!! here is not update 1 belief ! it update part of serveral beliefs !!!!

- self.beliefs = newBelief

Let's thought about something different. Let's say you look at that, and you say all right I get these variable eliminations, I can compute big tables of probability distribution over X , and I can do these online , I can do these on step-by-step update. But there's actually a couple problems.

One question is there's enough sums and products that can kind of become a little unclear what the equations doing until you're familiar with it. That's a temporary problem but there are permanent problems as well with the exact inference.

One is sometimes the space X is really really big and there's almost no chance that you're at anywhere except a couple locations. So think about you discrete tile compus down to 100 cm x 100 cm , and you have a robot that's right here . You started here and you run it for a minute but you kind of don't know if it's going to be 3 feet of 7 feet in that direction. But youk know that it's not going to kind of be in sproul plaza. So you have the giant state-space , you're only using a small little piece of it and so somehow we like to not have to have our computation be proportional to the number of states and in fact is proportional to the O(n²).

Secondly there are more complicated versions of HMMs called dynamic business for which inference actually gets quite difficult.

So what are we gonna do ?

We are going to replace the idea of a probability distribution that for each possible value of X returns your number -- was a lookup table for every state you get a numbe. Instead we're going to keep around a collection of hypotheses that may or may not be correct , and the hypotheses are going to embody a distribution as samples. So it's going to look something like this : you got a map ,and instead of each 10cm² piece of that map, having a tiny probability attached on it, I'm just going to have 300 places I might be. Now if I look these samples I don't exactly know where I am. Each sample says something different but I would guess that I'm somewhere in the upper right. And that's the idea.

- Filtering: approximate solution

- Sometimes |X| is too big to use exact inference

- |X| may be too big to even store B(X)

- E.g. X is continuous

- Solution: approximate inference

- Track samples of X, not all values

- instead of keeping track of a map from X to real numbers , I'm gonna keep track of a list of samples.

- here are 10 samples each red dot is a sample

- and in this case my samples live on some but not all of the location on the grid.

- Samples are called particles

- Time per step is linear in the number of samples

- But: number needed may be large

- In memory: list of particles, not states

- Track samples of X, not all values

- This is how robot localization works in practice

- Particle is just new name for sample

- Our representation of P(X) is now a list of N particles (samples)

- Generally, N << |X|

- Storing map from X to counts would defeat the point

- here instead of writing 9 numbers which is 1 probability for each square I'm gonna have maybe 10 particles.

- Each particle has a specific value of X , eg. green particle (3,3), and it's not the only particle that represents that hypothesis , we actually have 5 completely different particle that all predicting the same state.

- so what's the probability of (3,3) ? 50% ! It's probably wrong but that's what the particles say.

- P(x) approximated by number of particles with value x

- So, many x may have P(x) = 0!

- More particles, more accuracy

- For now, all particles have a weight of 1

Now what do I do ? I might start with my particles uniform or I have some particular belief and when time passes I need to move these particles around to reflect that. So I pick up each particle -- let's pick up the green one , a hypothesis of (3,3) -- where will it be next time in the next time slice? Well I grab my transition model -- which might say counterclockwise motion with high probability -- , so I grap this particle and I say you're no longer a distribution, you're a single value of X , you maybe wrong but you'er a single value of X and for that particular value of X.

- Each particle is moved by sampling its next position from the transition model

x' = sample( P(X'|x) )- This is like prior sampling -- samples’ frequencies reflect the transition probabilities

- Here, most samples move clockwise, but some move in another direction or stay in place

- 解释:

- I have a transition function

P(X'|x)that says from that specific square here is where I go in with what probability. - Now this is one particle and I can't do all of the things that might happen. So I flip a coin, this is a sampling. I take this particle and I pick one of the things that might evolve into , and I pick in proportion to the conditional proabability given by the transition function. So I get a new sampe

x', which might be in the same place or it might go couterclockwise. and if I do that to each one of these 10 particles I might get these 10 particles(bottom of pic) out. - I don't create particles , don't destroy particles, I picked them up 1 by 1 and I simulate what might happen to that particle in the next time step.

- so there might be 5 particles on (3,3) but they might not all get the same future because I flip a coin for each one. They might spread out in this case they do.

- I have a transition function

- This captures the passage of time

- If enough samples, close to exact values before and after (consistent)

- so someone gives me a HMM, that means they've given me the transition probabilities. I take my particles and each particle get simulated. That is like letting time pass in my model. That's how in particle filtering time passes.

What happens when I get evidence ? It's a little tricky.

- Slightly trickier:

- Don’t sample observation, fix it

- Similar to likelihood weighting, downweight samples based on the evidence

- w(x) = P(e|x)

- B(X) ∝ P(e|X)B'(x)

- As before, the probabilities don’t sum to one, since all have been downweighted (in fact they now sum to (N times) an approximation of P(e))

Let's say here are my 10 particles . What happens when I get evidence that there's a reading of red meaning the ghost is close right here in this square (3,2). We'll remember how evidence works in the that case: I take each of my probabilities and I downweighted by the probability of the evidence. In that analog of that here is to take each of your particles and give it a weight that reflects how likely the evidence is from that location. So this green particle at (3,2) maybe the probability of seeing red if you actually are at (3,2) is 0.9. So this is a reasonable hypothesis. But this guy at top-left square has a very low probability of seeing this reading.

So when time passed I just picked a future -- just like regular sampling , but here I'm stuck with the observation I have. So instead of generating it I force each sample to accept this future and some of them accept with a high probability and some of them accept with a low probability , and now there tiny little samples that have small weight.

There's one more trick. If I did this my samples would kind of go all over the place , and rather than clustering in the high probability regions , they just kind of drift around and some of them will get big weights and some of them will get small. So I'd like to as samples become very small , I'd like to kind of naturally and correctly have samples move over to where they're needed. And the way that works is even though I'm strictly speaking multiplying the each sample by the evidence weight is enough to incorporate the evidence I want to get back to unweighted samples that we're kind of the look where samples all have the same weight and tend to cluster in high probability regions.

- Rather than tracking weighted samples, we resample

- we're not going to track these samples under their weights. So I line up my 10 weighted samples , and I get 10 new ones according to my distribution.

- So we're going to get 10 new particles , and for each new particle we're gonna pick one of the old ones in proportion to their weights.

- That means (3,2) had a pretty high weight. So even though we get rid of all the old particles there going to be a lot of new ones which choose (3,2).

- So you go from the position like in top of pic, where part of the information of the distribution is in the location of the hypothesis -- the particles, and part of it is in their weights. You now have a new sampling ( bottom of pic ) , where all of the information is in their location -- they are now equally weighted. Where did the weights go? They went into the multiplicities -- the fact (3,2) has a high weight leads to more particles get clone from it , and (1,3) has a low weight that's reflected in the fact that probably it's not going to get chosen for the new team.

- N times, we choose from our weighted sample distribution (i.e. draw with replacement)

- This is equivalent to renormalizing the distribution

- procedurally the idea is when you see evidence in your particle filter , you line up your particles , you weight them by the evidence and then you clone new particles through your old particles , and now the weights are all gone.

- Now the update is complete for this time step, continue with the next one

- Particles: track samples of states rather than an explicit distribution

You have some belief function. It is represented by a list of particles of things that might be true , and they are all kind of the particles represent your distribution at samples.

When time passes, you take your particles and you don't add or delete particles. For each one you pick a future for it through simulation -- you flip coin. That's like prior sampling.

When evidence comes in , you weight the particles based on a factor from the evidence , so some particles get shrunk down to almost zero, other particles that match the evidence still have a pretty substantial weight.

Then you decide you don't actually want these weighted particles. So you resample and new() particles and each one clones an old particle , that means some old particles now kind of have multiplicity and some of them are gone.

Implementation

- Initialize particles by sampling from initial state distribution

- Repeat

- Perform time update

- Weight according to evidence

- corner case: When all your particles receive zero weight based on the evidence, you should resample all particles to initial distribution

- Resample according to weights

- Note: for partical filtering , you no need to store beliefs, current belief is stored in particles

- difference :

- sample

- Forward Algorithm : you consider all possible positions

- particle filtering : you consider just particles.

- time elapse

- Forward Algorithm : you consider how likely it is to get to Xt+1 from each locations (X').

- particle filtering : you just roll a dice, and move particle to next most likely position.

- sample

Question:

- use a particle filter to track the state of a robot that is lost in the small map below

- robot state: 1 ≤ Xt ≤ 10

- particles: approximate our belief over this state with N = 8 particles

- transition: At each timestep, the robot either stays in place, or moves to any one of its neighboring locations, all with equal probability

- eg. if the robot starts in state Xt = 2 , the next state Xt+1 can be any element of { 1 , 2 , 3 , 10 } , and each occurs with probability 1/4 .

- evidence: a sensor on the robot gives a reading Et ∈ {H,T,C,D}, corresponding to the type of state the robot is in. The possible types are:

- Hallway (H) for states bordered by two parallel walls (4,9).

- Corner (C) for states bordered by two orthogonal walls (3,5,8,10).

- Tee (T) for states bordered by one wall (2,6).

- Dead End (D) for states bordered by three walls (1,7).

- The sensor is not very reliable: it reports the correct type with probability 1/2 , but gives erroneous readings the rest of the time, with probability 1/6 for each of the three other possible readings.

So the Sensor Model is : (only list P(Sensor | H ))

| Sensor Reading | State Type | P(Sensor | State Type) |

|---|---|---|

| H | H | 0.5 |

| T | H | 1/6 |

| C | H | 1/6 |

| D | H | 1/6 |

| H | T | 1/6 |

| T | T | 0.5 |

| ... | ... | ... |

step1: Initialize particles by sampling from initial state distribution, for t=0.

- sample the starting positions for our particles , by generating a random number rᵢ sampled uniformly from [ 0 , 1).

| Particle | p₁ | p₂ | p₃ | p₄ | p₅ | p₆ | p₇ | p₈ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rᵢ | 0.914 | 0.473 | 0.679 | 0.879 | 0.212 | 0.024 | 0.458 | 0.154 |

| Location | 10 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 2 |

step2: Time update from t=0 → t=1.

- 移动每个粒子

- eg. p₈ 在 location 2,可能的移动为 { 1 , 2 , 3 , 10 }, 产生另一个 random number ,来执行移动

| Particle | p₁ | p₂ | p₃ | p₄ | p₅ | p₆ | p₇ | p₈ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rᵢ | 0.674 | 0.119 | 0.748 | 0.802 | 0.357 | 0.736 | 0.425 | 0.058 |

| Location | 10 | 4 | 7 | 10 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 |

step3: Incorporating Evidence at t = 1 : E₁ = D

- Weight according to evidence , weight = P( e | X )

- 当证据出现时,step2 做的预测 ,可能性会出现变化

| Particle | p₁ | p₂ | p₃ | p₄ | p₅ | p₆ | p₇ | p₈ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight | 1/6 | 1/6 | 0.5 | 1/6 | 1/6 | 1/6 | 1/6 | 0.5 |

step4: Resample according to weights

- normalize weights

- 计算 cumulative weights

- 生成 uniform random , sample new particle

| Particle | p₁ | p₂ | p₃ | p₄ | p₅ | p₆ | p₇ | p₈ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | 10 | 4 | 7 | 10 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 |

| Weight | 1/6 | 1/6 | 0.5 | 1/6 | 1/6 | 1/6 | 1/6 | 0.5 |

| normalized weight | 1/12 | 1/12 | 0.25 | 1/12 | 1/12 | 1/12 | 1/12 | 0.25 |

| Cumulative weight | 1/12=0.083 | 2/12=0.167 | 5/12=0.417 | 0.5 | 7/12=0.583 | 8/12=0.667 | 9/12=0.75 | 1 |

| rᵢ | 0.403 | 0.218 | 0.217 | 0.826 | 0.717 | 0.460 | 0.794 | 0.016 |

| new particle (clone) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 8 | 7 | 4 | 8 | 1 |

| new location | 7 | 7 | 7 | 1 | 5 | 10 | 1 | 10 |