- What is Alfred?

- Features

- Example Use Cases

- Tasks

- Task components

- Arguments, Variables and Templates Oh My!

- Alfred files getting too large?

- Tab completion

Alfred is a simple yaml based task runner. It helps automate tedious tasks among many things. I built it primarily as a replacement to docker-compose as an evolution to Yoda however it's grown into something a bit bigger. It's been used for all kinds of automated tasks, and has become part of my daily workflow automating tedious tasks I was previously doing by hand. Another reason it's been great is the automation of dev workflows. Setting up configuration files, creating symlinks, running all sorts of commands in the proper order in order to get dev boxes up and running as quickly as possible. Get

- Extendable. Common tasks(Private too)

- Watch files for modifications

- Retry/Rerun tasks based on failures before giving up

- Logging

- Success/Failure decision tree

- Run tasks asynchronously or synchronously

- Autocomplete task names

- Many more!

I've used alfred for many things, and as I build commonly run tasks I try to share them via remote modules. Some examples.

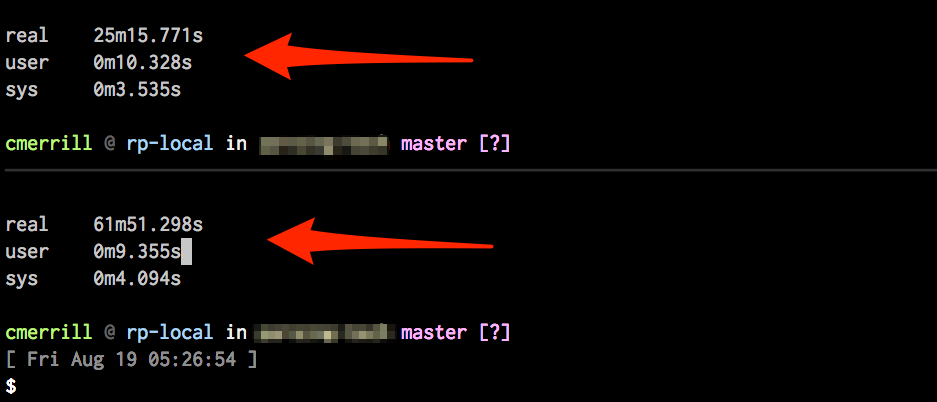

I like docker and docker-compose, but it was lacking for some of my needs. The inability to pull/build images in parallel was frustrating. Especially in larger build systems. On top of that, docker-compose does one thing and it does it really well. The problem with docker is when it comes to dev box orchestration in my opinion. Setting up symlinks, moving configs here and there. Starting up microservices in just the right order, putting code exactly in differnet spots and coordinating multiple git repos became a nightmare. This is a pretty common example of using alfred to setup a dev env. By pulling, building and running multiple microservices(20+) we were able to take build times and cut them literally in half.

By posting metrics on success or failure and setting up alerting we were able to use alfred as a cron job monitor. Here is an example file:

* * 1 * * alfred monitor python somescript.py

monitor:

summary: Monitor a specific cron job

command: {{ .AllArgs }}

ok: success

fail: failed

ok:

summary: Send ok data point to datadog agent

command: |

echo "cron.{{ index .Args 1 }}.ok:1|c|#cron" | nc -w 1 -u 0.0.0.0 8125

private: true

failed:

summary: Send failure data point to datadog agent

command: |

echo "cron.{{ index .Args 1 }}.failed:1|c|#cron" | nc -w 1 -u 0.0.0.0 8125

private: true

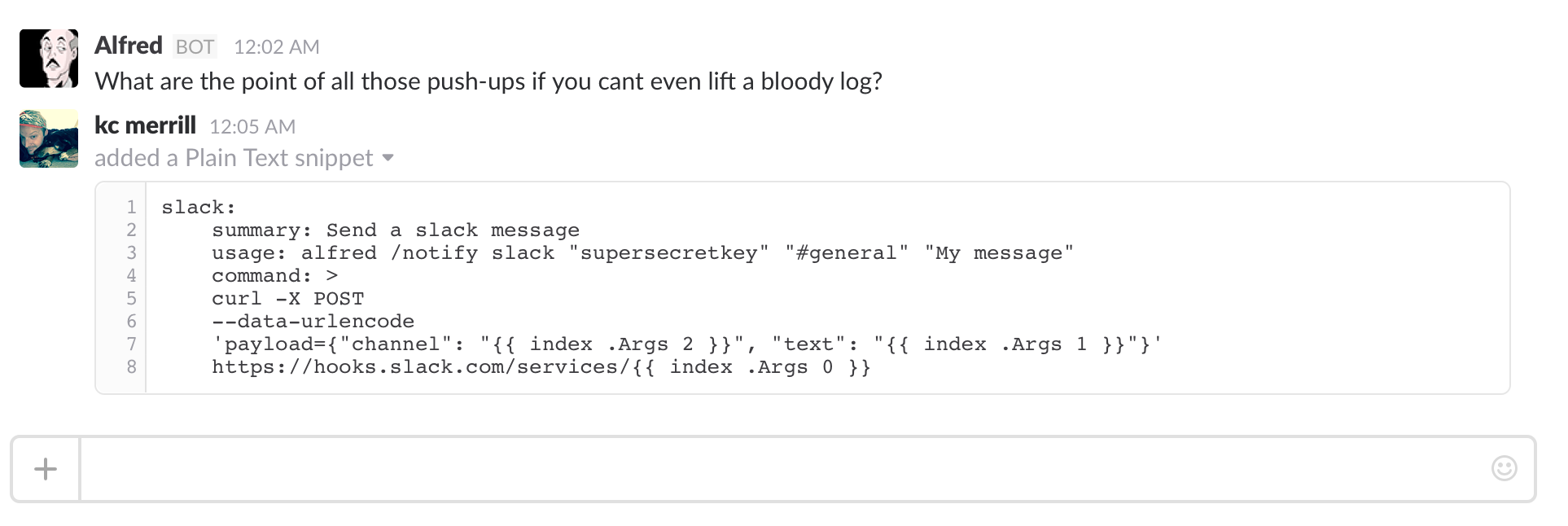

By leveraging the common modules, in this case slack, alfred will post into a slack channel letting you know that your website is down.

`alfred /http.slack "kcmerrill.com" "supersecretslackkey"`

http.slack:

summary: HTTP Check

usage: alfred /http.slack "website" "supersecretkey"

dir: /tmp/http/{{ index .Args 0 }}

command: wget {{ index .Args 0 }}

ok: cleanup

fail: send.notification

every: 10s

send.notification:

dir: /tmp/http/{{ index .Args 0 }}

command: test ! -f last_notified || test $(find -amin +{{ index .Args 2 }} | wc -l) -ge "2"

private: true

ok: notify

defaults:

- ""

- ""

- "10"

notify:

dir: /tmp/http/{{ index .Args 0 }}

summary: Send slack notification

notify: slack "{{ index .Args 1 }}" "{{ index .Args 0 }} is down"

command: touch last_notified

cleanup:

dir: /tmp/http/{{ index .Args 0 }}

command: |

rm -rf last_notified

rm -rf index.html*

The way I think of tasks are like reusable functions but for shell scripts. They are built using components(just YAML key/value combinations). Your tasks can be anything you need/want them to be, and there isn't any required components. The only requirement is you use at least one. If not at least one, then there isn't a point to a task!

Name the task whatever you'd like. Having built quite a few projects I'd recommend you come up with a naming convention.

While formally, there is no such thing as task groups, using a . in the name is a great way of identifying groups of tasks. By "grouping" tasks together using a good naming convention will make it easier for those using your task file to know what's going on. what.action is a typical approach.

Examples:

servicea.buildservicea.destroydocker.run.webdocker.run.db

Task names with an * at the end of it's name denotes it's an "important" task. Important tasks are useful when your alfred.yml file gets rather large and you have a bunch of tasks, tasks that can be run from the command line and are not private, but perhaps not as useful as others. These tasks are showed at the bottom of the list output when running alfred and tend to stick out more than a normal task.

a.basic.task:

summary: I am a basic task

command: |

echo "hello world"

important.task*:

summary: I am important! I show up at the bottom of the list(which is most visible to devs using me!)

command: |

echo "I am important I say!"

It might help to call your tasks with parameters for example with tasks, setup, multitask, ok, fail as examples. If we were to rewrite the original demo example using params it would look something like this.

say:

summary: I will say what you send me!

usage: alfred say hello

command: echo {{ index .Args 0 }}

speak:

tasks: say(hello) say(goodbye)

blurt:

multitask: say(hello) say(goodbye)If you do call a task with params, all tasks that get called must have () even if they do NOT have params. The reason? I was lazy and didn't come up with a robust solution to fix this. It's either all or nothing.

Alfred comes with multiple components built in. A task can be as simple or as complex as you want to make it. It's really up to you. A task can have one or many components. Lets go over what's available to you, and more importantly, it's order that it's run within the task. By default, all alfred commands are run at the root level where alfred.yml exists.

An alias maps back to the task name. Sometimes it helps to name a task multiple things, without copying the contents of the task. When set it's a space separated string of names

A few things to note:

- Be careful not to have an alias that matches another task name.

my.task:

summary: My task! Woot woot!

command: >

echo

"hello

world"

This component is the first to be called. It's a string of space seperated task names. Useful if you need tasks to run before this task is run.

run.first:

summary: A task to be run before the main task

main.task

summary: The main task

setup: run.first

command: echo "the task run.first would be run before this task"

If set and not an empty string, represents a filename in which stdout will be sent to.

A few things to note:

- Relative paths are relative to the

alfred.ymlfile - If the location is not writable, no logs are saved. Make sure all dirs exist and are writeable.

- Only the command of the given task gets logged. All of it's sub tasks will not be logged.

Example use cases:

- Show build errors without rerunning entire tasks over again.

mytask:

summary: Lets log "hello world!"

log: /tmp/hello_world.txt

command: |

echo "hello world!"

The default starting location for this particular task. If set to a non empty string, will create the directory if not exist.

A few things to note:

- Relative paths are relative to the

alfred.ymlfile. - Directories that do not exist will attempt to be created. If unable, the task will fail.

- Be careful when used in multitask(not guarenteed the dir due to other tasks). Setup your tasks accordingly.

- Every task starts by default to the location of the alfred, including tasks run after

diris set. diris for this task only, and not for any downstream tasks.

example.task:

summary: Will change this task to the specified directory

dir: /tmp

command: |

echo "The current working directory is now /tmp regardless of alfred file!"

If set to a non empty string, will watch for file modifications times to change. The string given should be a regular expression of file patterns to match against.

Example use cases:

- TDD, when files change, build, run tests

- Minify, lint or format code changes upon file changes

A few things to note:

- This will override the

everycomponent to1s, and will check file changes with a1spause. watchhalts execution of the task, and when a file modification is found, continues on.- Is relative to the

dircomponent. Ifdiris not set, relative toalfred.ymlfile.

test:

summary: Testing ...

command: |

go test -v

tdd:

summary: Watch for code changes and run tests when .go files are modified

watch: "*.go$"

tasks: test

A string separated list of tasks to be run in order provided. Each task is run in order as if it were it's own standalone task. If no exits, will return accordingly. Can be used instead of setup if no setup tasks are required.

task.one:

summary: Task One!

command: echo "task one!"

task.two:

summary: Task Two!

command: echo "task two!"

task.three:

summary: The third and final act!

tasks: task.one task.two

command: echo "task three!"

Alfred's way of extending it's functionality, modules, are key value yaml pairs that repesent a github username/project: task. The project should contain a valid alfred.yml file or configuration at it's root level. So lets say you have a github project with an alfred file, you can interact with that alfred file without actually having it on your machine. Simply put, remote modules are remote alfred.yml files.

Example use cases:

- Create a number of reusable components that you can make private or shared.

- Extend alfred and make it extensible.

- Setup github projects with one command.

alfred /project kcmerrill/yoda - Create common tasks with your team with one centralized location

A few things to note:

- You can add additional repositories, not just github. See below.

- Alfred comes with a built in webserver to serve up your own remote modules.

- The convention is

username/project, by default alfred points to itself(on github).github.com/kcmerrill/alfred/tree/master/modules. - This does execute remote code so be careful and be sure to trust the source!

- Remote modules are not cached, which has it's pros and cons. With great power comes great responsibility.

This is the notify module in action. alfred /notify slack ...

# Used to self update itself. See the `self` folder in modules for additional information

$ alfred /self update

# Used to install a github repo and run `alfred install` inside

$ alfred kcmerrill/yoda

start.container:

docker: kill.remove mycontainer

command: |

docker run -P -d mycontainer

If a remote isn't found, alfred will default to github as described above. If you have alfred files that you'd like to keep private, but you'd like to share with your team, you can simply start a static webserver(alfred comes built in with one). alfred --serve --dir . --port 80 Where directory is the files to serve, and port is the posrt to listen on.

To allow alfred to access these files, you'll need to create a configuration file located here: $HOME/.alfred/config.yml. Contained within this config file, is a key repos which will container a key value pair. The key will be something you define. So walk through an example. We will pretend your using these private repos for work, and you work for companyxyz.

$ cd /tmp

$ mkdir companyxyzalfredfiles

# start a static webserver here.

$ alfred --serve --port 8080

# lets create a few folders to organize our alfred files(this is required).

$ mkdir projectX

$ touch projectX/alfred.yml

# inside projectX/alfred.yml, is your standard alfred file with tasks in it.

$ mkdir projectY

$ touch projectY/alfred.yml, is your standard alfred file with tasks in it.

Ok, now that you have a location of private alfred files with a static webserver running on port 8080, lets add it to the repos section to your $HOME/.alfred/config.yml

remote:

companyxyz: http://localhost:8080/

Now, companyxyz is the key ... and we know we have projectX and projectY located at http://localhost:8080.

To use the remote module you'd simply do:

alfred companyxyz/projectX <taskname>

or to list out the tasks located under projectX simply do:

alfred companyxyz/projectX

Of course, you can use whatever else is situated there as well, so you can also do something like this:

alfred companyxyz/projectY

etc etc ...

In order to ensure these are really private, make sure http://localhost:8080 can only be accessible by those whom you are ok reading in the .alfred files and it's tasks.

I was using localhost as an example, but note that you can replace localhost with whatever url the static webserver is located.

A brief text descrption to let the end user know what the general idea of the task is. Visible when listing out the tasks

my.simple.task:

summary: I will echo out everytime I'm run!

A string representation of a string variable to be stored for later use by other tasks. The variable that is stored is the stderr/stdout from command component.

fourty.one:

summary: Register a variable

register: my.new.var

command: |

echo "5678"

fourty.two:

setup: fourty.one

summary: Retrieve a registered variable

command: |

echo The variable is {{ index .Vars "my.new.var"}}Example use cases:

- Use to store changing information per alfred run, but needed throughout all tasks

A few things to note:

- Either stderr or stdout will be saved

- If you define

alfred.vars, be careful the names you choose, as you can overwrite a previously defined variable.

A shell command that should return a proper exit code before continuing. Should it fail, the task will fail and will continue on to the fail tasks, then to exit or skip depending on whatever was set.

Example use cases:

- Before running a task that interacts with a file, check it's existance first without needing to create another task.

- Test to see if certain things are installed. Using

wget?unzip? Verify it's insalled first.

A few things to note:

- It's currently a shell command. It's exit code determines if the task fails or not.

- It's silent, meaning it's output is not shown to the end user. This can make initial debugging harder but it keeps the

alfred.ymlfile tidy.

download.url:

summary: Lets download google.com's page

test: which wget

fail: install.wget

command: |

wget http://www.google.com

An integer value, if set to a non zero value will retry the command component X number of times before giving up.

pesky.task:

summary: This task may/may not run on the first time. Try at least 10 times before all hope is lost

command: |

python pesky.script.py

retry: 10

A string that gets sent to bash -c. Based upon it's error code, will determine if the task is succesful or fails.

A few things to note:

- By using the

|in yaml, you can have multiple commands, however, the success/failure is only the last command run. - By using the

>in yaml, you can have a multiline command. Yaml converts newlines to spaces. Useful for a really long command without needing to use\. - Without exit codes, Checking out muliple git repos.

- You can call alfred from here need be.

- Omitting

commandor by supplying an empty string will always be skipped and marked as succesful, continuing the task.

dont.care.about.exit.codes:

summary: Lets checkout some repositories. Who cares about exit codes, probably already checked out!

command: |

git clone [email protected]/username/projectA

# regardless of exit code, continue ...

git clone [email protected]/username/projectB

# regardless of exit code, continue ...

git clone [email protected]/username/projectC

# regardless of exit code, continue ...

git clone [email protected]/username/projectD

# note, the last command to be run, it's exit code determines exit/skip/ok/fail components if they are set.

a.really.long.cmd:

summary: This is a really long command, lets say a long docker run command.

command: >

docker run

-d

-P

--name mycontainer

username/image:tag

Nearly identical to command however, each line is evaluated independantly based upon it's success/failure. Meaning each line and each command is interpreted as if it were it's own command and alfred will respond accordingly.

A few things to note:

- Omitting

commandsor by supplying an empty string will always be skipped and marked as succesful, continuing the task.

checkout.repos:

summary: Checkout repositories, fail if any do not exist

commands: |

git clone [email protected]/username/projectA

# projectA must _NOT_ have been checked out already, or do not continue

git clone [email protected]/username/projectB

git clone [email protected]/username/projectC

git clone [email protected]/username/projectD

# We can only make it here if all the commands, or each line representing a command exited properly.

If not an empty string, will be the port number in which to serve a static webserver.

Example use cases:

- JS programming

- Get a dev/api sandbox up and running quickly(just serve json endpoints)

A few things to note:

- When alfred exits, the server will exit

- If you need a long running server without running other tasks use

waitand a long duration - No need to multitask, simply serve and continue on ...

- By default, serve's documentroot will be relative to the

alfred.ymlfile unless thedircomponent is set

static.webserver:

summary: Start a static webserver on port 8000

serve: 8000

If not an empty string, wait takes a golang string time duration. So 1h, 1s etc ... See golang time duration documentation for more information.

Example use cases:

- Check service every few seconds to make sure it comes online before running the next task.

A few things to note:

- If duration is not able to be parsed properly, it will be skipped as if it were not set.

- If

watchis enabled, this will be overwritten with1s

say.hello:

summary: Lets say hello every 5 seconds!

wait: 5s

every: 0s

command: |

echo "Hello $USER!"

A string which is a space separated list of tasks to run if the task has failed up to this point. Identical to ok.

Example use cases:

- When a

commandcompletes with an error, perform other actions such as cleanup, monitoring etc ... - Halt the build process, or cleanup running processes for the task's next run.

- HTTP/Service check. If failure, send metrics indicating so.

A few things to note:

- Tasks continue on to the next task in the list unless the exit is provoked at which point the process stops

http.check

summary: HTTP check -> Data dog

test: which wget

command: |

wget echo -n "custom_metric:60|g|#shell" >/dev/udp/localhost/8125

every: 1h

ok: up.metric

fail: down.metric

up.metric:

summary: Sending in an up metric! Woot!

command: |

echo -n "http.check.up:60|g|#shell" >/dev/udp/localhost/8125

private: true

down.metric:

summary: Sending a down metric! #sadpanda

command: |

echo -n "http.check.down:60|g|#shell" >/dev/udp/localhost/8125

private: true

A boolean, which if set to true will be omitted from the listing of tasks. Private tasks can only be run from other tasks from within alfred, and cannot be run from the command line.

Example use cases: - Some tasks are dependant on other tasks to be setup, etc ... make sure they cannot be run - Hide tasks from the list of tasks

A few things to note:

- tasks cannot be run from the command line. They can only be called from other tasks within alfred.

- tasks will not be shown when alfred is called in list mode.

example.task:

summary: This task does a bunch of stuff

command: |

# do a bunch of stuff, that _must_ be done before the next task can be run.

ok: next.task

next.task

summary: I cannot be run without example.task to be run ...

command: |

echo "I am doing something important, but cannot be a standalone task!"

private: true

Haults the entire task. If you're running ok, or fail tasks, the only way to stop continuation is to exit. If you do not wish to exit, this will continue onto the next task.

A few things to note:

- Identical to exit, without actually exiting. Just continues on to the next task.

task.one:

summary: Task one!

task.two:

summary: Task two!

task.three:

summary:

on.failure:

summary: Stop processing this task, but continue on!

command: |

ls /doesnotexist #to simulate a failure

skip: true

A number, which if is not 0, haults the entire process if the task should fail. A bad command, commands etc ... exiting with the value given

Example use cases:

- If tests fail within a build, exit the application with a non zero exit code haulting deployment.

- Processes should stop if certain things are done incorrectly, or if applications are not installed.

A few things to note:

- This haults the entire application. No further action is taken.

bad.task:

summary: This task will fail

command: |

echo "Goodbye world :(" && false

exit: 10

A space separated list of task names that can be run in parallel.

Example use cases:

- Pulling/Building/Deleting docker images

- Setting up multiple dev projects at once

A few things to note:

- Avoid changing directories or using the

dirkey as this might impact your other tasks - The logging will appear different. It will be taskname | taskoutput

- A lot of applications use stdout as a way to filter debuggign information,

alfredshows this astaskname:erroreven though it might not be an error.

run.many.tasks

summary: This task will call a bunch of other tasks at the SAME time

multitask: taska taskb taskc taskd

A string which is space separated list of tasks to be run if the task was succesful to this point.

Example use cases:

- When a

commandcompletes succesfully, perform other actions such as cleanup, monitoring etc ... - A continuation of a build process if tests passed. Deploy for example.

- HTTP/Service check. If ok, send metrics indicating so. Same thing with fail.

A few things to note:

- Tasks continue on to the next task in the list unless the exit is provoked at which point the process stops

http.check

summary: HTTP check -> Data dog

test: which wget

command: |

wget echo -n "custom_metric:60|g|#shell" >/dev/udp/localhost/8125

every: 1h

ok: up.metric

fail: down.metric

up.metric:

summary: Sending in an up metric! Woot!

command: |

echo -n "http.check.up:60|g|#shell" >/dev/udp/localhost/8125

private: true

down.metric:

summary: Sending a down metric! #sadpanda

command: |

echo -n "http.check.down:60|g|#shell" >/dev/udp/localhost/8125

private: true

A golang string duration representing how often this task should run. A task with every: 10s will run every ten seconds.

Example use cases:

- HTTP checks

- File System checks

- Monitoring

A few things to note:

skipandexitwill invalidateevery.- When

everyis set, it's an infinite loop and will need to be cancelled manually, or throughexitorskip

say.hello:

summary: Saying hello every second!

every: 1s

Alfred allows the use of variables and arguments to be passed in. This allows tasks to be reusable bits of code. Using alfred task.name zero one two three etc as our example, the argument immediately following the task.name start at index zero. Knowing this, you can then inject this into a wide variety of task components. By using the defaults task component, you can set the defaults too.

do.you.know:

summary: Do you know?

command: |

echo "Do you know {{ index .Args 0 }}

defaults:

- The muffin man

$ alfred do.you.know

// Do you know The muffin man

If you do not specify defaults, alfred will exit due to insufficient arguments passed in.

Every task is injected with the time that the particular task started. You can use it in your task by using {{ .Time }}

task.name:

summary: Another task!

command: |

echo "The date/time object you can play with can be found here: {{ .Time }}"

echo "The epoch time is: {{ .Time.Unix }}

Every task is injected with a UUID4 string. You can use it in your task by using {{ .UUID }}

another.task:

summary: Woot! Another task

command: |

echo The UUID is {{ .UUID }}

You can break up your alfred files in multiple ways. The following are glob patterns that can be used:/alfred.yml, /.alfred/*alfred.yml, /alfred/*alfred.yml. As an example, you can create a directory called alfred or .alfred or just create mutliple alfred files.

Copy the included alfred.completion.sh to /etc/bash_completion.d/, or source it in your ~/.profile file.