There a number of common user interface patterns that can be implemented using Qt Quick Controls. In this section, we try to demonstrate how some of the more common ones can be built.

For this example we will create a tree of pages that can be reached from the previous level of screens. The structure is pictured below.

The key component in this type of user interface is the StackView. It allows us to place pages on a stack which then can be popped when the user wants to go back. In the example here, we will show how this can be implemented.

The initial home screen of the application is shown in the figure below.

The application starts in main.qml, where we have an ApplicationWindow containing a ToolBar, a Drawer, a StackView and a home page element, Home. We will look into each of the components below.

import QtQuick

import QtQuick.Controls

ApplicationWindow {

// ...

header: ToolBar {

// ...

}

Drawer {

// ...

}

StackView {

id: stackView

anchors.fill: parent

initialItem: Home {}

}

}The home page, Home.qml consists of a Page, which is n control element that support headers and footers. In this example we simply center a Label with the text Home Screen on the page. This works because the contents of a StackView automatically fill the stack view, so the page will have the right size for this to work.

<<< @/docs/ch06-controls/src/interface-stack/Home.qml

Returning to main.qml, we now look at the drawer part. This is where the navigation to the pages begin. The active parts of the user interface are the ÌtemDelegate items. In the onClicked handler, the next page is pushed onto the stackView.

As shown in the code below, it is possible to push either a Component or a reference to a specific QML file. Either way results in a new instance being created and pushed onto the stack.

ApplicationWindow {

// ...

Drawer {

id: drawer

width: window.width * 0.66

height: window.height

Column {

anchors.fill: parent

ItemDelegate {

text: qsTr("Profile")

width: parent.width

onClicked: {

stackView.push("Profile.qml")

drawer.close()

}

}

ItemDelegate {

text: qsTr("About")

width: parent.width

onClicked: {

stackView.push(aboutPage)

drawer.close()

}

}

}

}

// ...

Component {

id: aboutPage

About {}

}

// ...

}The other half of the puzzle is the toolbar. The idea is that a back button is shown when the stackView contains more than one page, otherwise a menu button is shown. The logic for this can be seen in the text property where the "\\u..." strings represents the unicode symbols that we need.

In the onClicked handler, we can see that when there is more than one page on the stack, the stack is popped, i.e. the top page is removed. If the stack contains only one item, i.e. the home screen, the drawer is opened.

Below the ToolBar, there is a Label. This element shows the title of each page in the center of the header.

ApplicationWindow {

// ...

header: ToolBar {

contentHeight: toolButton.implicitHeight

ToolButton {

id: toolButton

text: stackView.depth > 1 ? "\u25C0" : "\u2630"

font.pixelSize: Qt.application.font.pixelSize * 1.6

onClicked: {

if (stackView.depth > 1) {

stackView.pop()

} else {

drawer.open()

}

}

}

Label {

text: stackView.currentItem.title

anchors.centerIn: parent

}

}

// ...

}Now we’ve seen how to reach the About and Profile pages, but we also want to make it possible to reach the Edit Profile page from the Profile page. This is done via the Button on the Profile page. When the button is clicked, the EditProfile.qml file is pushed onto the StackView.

<<< @/docs/ch06-controls/src/interface-stack/Profile.qml

For this example we create a user interface consisting of three pages that the user can shift through. The pages are shown in the diagram below. This could be the interface of a health tracking app, tracking the current state, the user’s statistics and the overall statistics.

The illustration below shows how the Current page looks in the application. The main part of the screen is managed by a SwipeView, which is what enables the side by side screen interaction pattern. The title and text shown in the figure come from the page inside the SwipeView, while the PageIndicator (the three dots at the bottom) comes from main.qml and sits under the SwipeView. The page indicator shows the user which page is currently active, which helps when navigating.

Diving into main.qml, it consists of an ApplicationWindow with the SwipeView.

import QtQuick

import QtQuick.Controls

ApplicationWindow {

visible: true

width: 640

height: 480

title: qsTr("Side-by-side")

SwipeView {

// ...

}

// ...

}Inside the SwipeView each of the child pages are instantiated in the order they are to appear. They are Current, UserStats and TotalStats.

ApplicationWindow {

// ...

SwipeView {

id: swipeView

anchors.fill: parent

Current {

}

UserStats {

}

TotalStats {

}

}

// ...

}Finally, the count and currentIndex properties of the SwipeView are bound to the PageIndicator element. This completes the structure around the pages.

ApplicationWindow {

// ...

SwipeView {

id: swipeView

// ...

}

PageIndicator {

anchors.bottom: parent.bottom

anchors.horizontalCenter: parent.horizontalCenter

currentIndex: swipeView.currentIndex

count: swipeView.count

}

}Each page consists of a Page with a header consisting of a Label and some contents. For the Current and User Stats pages the contents consist of a simple Label, but for the Community Stats page, a back button is included.

import QtQuick

import QtQuick.Controls

Page {

header: Label {

text: qsTr("Community Stats")

font.pixelSize: Qt.application.font.pixelSize * 2

padding: 10

}

// ...

}The back button explicitly calls the setCurrentIndex of the SwipeView to set the index to zero, returning the user directly to the Current page. During each transition between pages the SwipeView provides a transition, so even when explicitly changing the index the user is given a sense of direction.

::: tip

When navigating in a SwipeView programatically it is important not to set the currentIndex by assignment in JavaScript. This is because doing so will break any QML bindings it overrides. Instead use the methods setCurrentIndex, incrementCurrentIndex, and decrementCurrentIndex. This preserves the QML bindings.

:::

Page {

// ...

Column {

anchors.centerIn: parent

spacing: 10

Label {

anchors.horizontalCenter: parent.horizontalCenter

text: qsTr("Community statistics")

}

Button {

anchors.horizontalCenter: parent.horizontalCenter

text: qsTr("Back")

onClicked: swipeView.setCurrentIndex(0);

}

}

}This example shows how to implement a desktop-oriented, document-centric user interface. The idea is to have one window per document. When opening a new document, a new window is opened. To the user, each window is a self-contained world with a single document.

The code starts from an ApplicationWindow with a File menu with the standard operations: New, Open, Save and Save As. We put this in the DocumentWindow.qml.

We import Qt.labs.platform for native dialogs, and have made the subsequent changes to the project file and main.cpp as described in the section on native dialogs above.

import QtQuick

import QtQuick.Controls

import Qt.labs.platform as NativeDialogs

ApplicationWindow {

id: root

// ...

menuBar: MenuBar {

Menu {

title: qsTr("&File")

MenuItem {

text: qsTr("&New")

icon.name: "document-new"

onTriggered: root.newDocument()

}

MenuSeparator {}

MenuItem {

text: qsTr("&Open")

icon.name: "document-open"

onTriggered: openDocument()

}

MenuItem {

text: qsTr("&Save")

icon.name: "document-save"

onTriggered: saveDocument()

}

MenuItem {

text: qsTr("Save &As...")

icon.name: "document-save-as"

onTriggered: saveAsDocument()

}

}

}

// ...

}To bootstrap the program, we create the first DocumentWindow instance from main.qml, which is the entry point of the application.

<<< @/docs/ch06-controls/src/interface-document-window/main.qml

In the example at the beginning of this chapter, each MenuItem calls a corresponding function when triggered. Let’s start with the New item, which calls the newDocument function.

The function, in turn, relies on the createNewDocument function, which dynamically creates a new element instance from the DocumentWindow.qml file, i.e. a new DocumentWindow instance. The reason for breaking out this part of the new function is that we use it when opening documents as well.

Notice that we do not provide a parent element when creating the new instance using createObject. This way, we create new top level elements. If we had provided the current document as parent to the next, the destruction of the parent window would lead to the destruction of the child windows.

ApplicationWindow {

// ...

function createNewDocument()

{

var component = Qt.createComponent("DocumentWindow.qml");

var window = component.createObject();

return window;

}

function newDocument()

{

var window = createNewDocument();

window.show();

}

// ...

}Looking at the Open item, we see that it calls the openDocument function. The function simply opens the openDialog, which lets the user pick a file to open. As we don’t have a document format, file extension or anything like that, the dialog has most properties set to their default value. In a real world application, this would be better configured.

In the onAccepted handler a new document window is instantiated using the createNewDocument method, and a file name is set before the window is shown. In this case, no real loading takes place.

::: tip

We imported the Qt.labs.platform module as NativeDialogs. This is because it provides a MenuItem that clashes with the MenuItem provided by the QtQuick.Controls module.

:::

ApplicationWindow {

// ...

function openDocument(fileName)

{

openDialog.open();

}

NativeDialogs.FileDialog {

id: openDialog

title: "Open"

folder: NativeDialogs.StandardPaths.writableLocation(NativeDialogs.StandardPaths.DocumentsLocation)

onAccepted: {

var window = root.createNewDocument();

window.fileName = openDialog.file;

window.show();

}

}

// ...

}The file name belongs to a pair of properties describing the document: fileName and isDirty. The fileName holds the file name of the document name and isDirty is set when the document has unsaved changes. This is used by the save and save as logic, which is shown below.

When trying to save a document without a name, the saveAsDocument is invoked. This results in a round-trip over the saveAsDialog, which sets a file name and then tries to save again in the onAccepted handler.

Notice that the saveAsDocument and saveDocument functions correspond to the Save As and Save menu items.

After having saved the document, in the saveDocument function, the tryingToClose property is checked. This flag is set if the save is the result of the user wanting to save a document when the window is being closed. As a consequence, the window is closed after the save operation has been performed. Again, no actual saving takes place in this example.

ApplicationWindow {

// ...

property bool isDirty: true // Has the document got unsaved changes?

property string fileName // The filename of the document

property bool tryingToClose: false // Is the window trying to close (but needs a file name first)?

// ...

function saveAsDocument()

{

saveAsDialog.open();

}

function saveDocument()

{

if (fileName.length === 0)

{

root.saveAsDocument();

}

else

{

// Save document here

console.log("Saving document")

root.isDirty = false;

if (root.tryingToClose)

root.close();

}

}

NativeDialogs.FileDialog {

id: saveAsDialog

title: "Save As"

folder: NativeDialogs.StandardPaths.writableLocation(NativeDialogs.StandardPaths.DocumentsLocation)

onAccepted: {

root.fileName = saveAsDialog.file

saveDocument();

}

onRejected: {

root.tryingToClose = false;

}

}

// ...

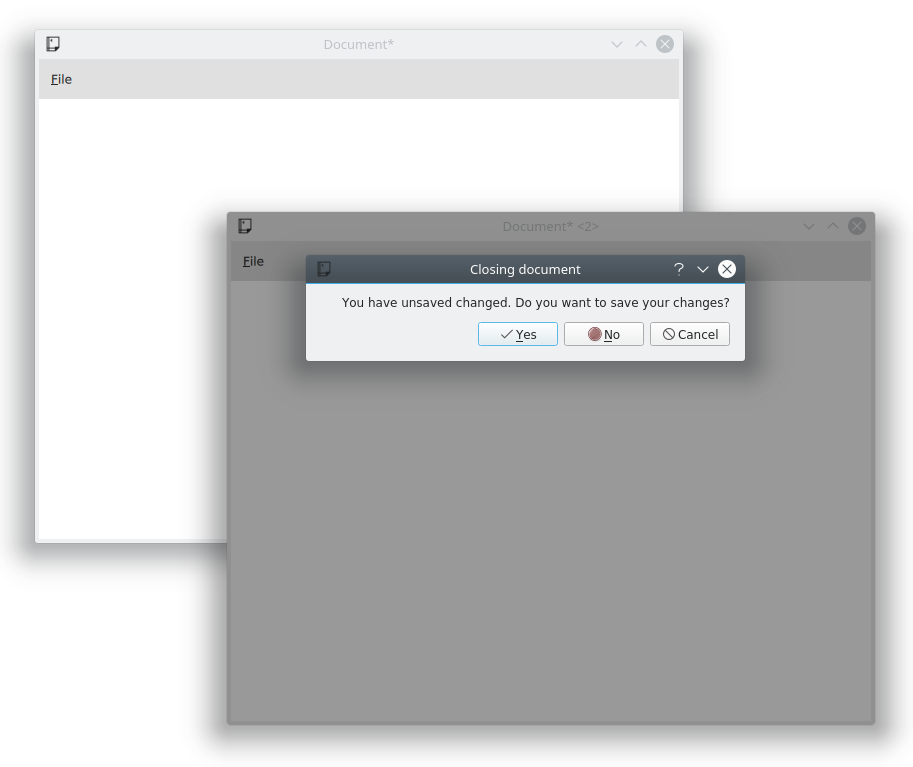

}This leads us to the closing of windows. When a window is being closed, the onClosing handler is invoked. Here, the code can choose not to accept the request to close. If the document has unsaved changes, we open the closeWarningDialog and reject the request to close.

The closeWarningDialog asks the user if the changes should be saved, but the user also has the option to cancel the close operation. The cancelling, handled in onRejected, is the easiest case, as we rejected the closing when the dialog was opened.

When the user does not want to save the changes, i.e. in onNoClicked, the isDirty flag is set to false and the window is closed again. This time around, the onClosing will accept the closure, as isDirty is false.

Finally, when the user wants to save the changes, we set the tryingToClose flag to true before calling save. This leads us to the save/save as logic.

ApplicationWindow {

// ...

onClosing: {

if (root.isDirty) {

closeWarningDialog.open();

close.accepted = false;

}

}

NativeDialogs.MessageDialog {

id: closeWarningDialog

title: "Closing document"

text: "You have unsaved changed. Do you want to save your changes?"

buttons: NativeDialogs.MessageDialog.Yes | NativeDialogs.MessageDialog.No | NativeDialogs.MessageDialog.Cancel

onYesClicked: {

// Attempt to save the document

root.tryingToClose = true;

root.saveDocument();

}

onNoClicked: {

// Close the window

root.isDirty = false;

root.close()

}

onRejected: {

// Do nothing, aborting the closing of the window

}

}

}The entire flow for the close and save/save as logic is shown below. The system is entered at the close state, while the closed and not closed states are outcomes.

This looks complicated compared to implementing this using Qt Widgets and C++. This is because the dialogs are not blocking to QML. This means that we cannot wait for the outcome of a dialog in a switch statement. Instead we need to remember the state and continue the operation in the respective onYesClicked, onNoClicked, onAccepted, and onRejected handlers.

The final piece of the puzzle is the window title. It is composed of the fileName and isDirty properties.

ApplicationWindow {

// ...

title: (fileName.length===0?qsTr("Document"):fileName) + (isDirty?"*":"")

// ...

}This example is far from complete. For instance, the document is never loaded or saved. Another missing piece is handling the case of closing all the windows in one go, i.e. exiting the application. For this function, a singleton maintaining a list of all current DocumentWindow instances is needed. However, this would only be another way to trigger the closing of a window, so the logic flow shown here is still valid.