Tradução e modificação do material associado a programmingforbiology.org, associado a disciplina "CEN0336 - Introdução a Programação de Computadores Aplicada a Ciências Biológicas"

Criador e Instrutor da versão em Português Diego M. Riaño-Pachón

Criadores do material na versão em Inglês Simon Prochnik Sofia Robb

Python é uma linguagem de script. Ela é útil para desenvolvimento de projetos científicos de médio porte. Quando você executa um script de Python, o interpretador da linguagem irá gerar um código em bytes e interpretá-lo. Esse processo acontece automaticamente, você não precisa se preocupar com isso. Linguagens compiladas como C e C++ vão rodar muito mais rapidamente, mas são também muito mais complicadas de programar. Programas usando linguagens como Java (que também são compiladas) são adequados para projetos grandes com programação colaborativa, mas não são executados tão rapidamente como C e são mais complexos de escrever que Python.

Python tem

- tipos de dados

- funções

- objetos

- classes

- métodos

Tipos de dados correspondem aos diferentes tipos de dados que serão discutidos em mais detalhes posteriormente. Exemplos de tipos de dados incluem números inteiros e cadeias de caracteres (texto). Eles podem ser armazenados em variáveis.

Funções fazem algo com dados, como cálculos. Algumas funções estão disponíveis de forma nativa em Python. Você pode também criar suas próprias funções.

Objetos correspondem a maneiras de agrupar conjuntos de dados e funções (métodos) que agem nestes dados.

Classes correspondem a uma maneira de encapsular (organizar) variáveis e funções. Objetos usam variáveis e métodos da classe às quais pertencem.

Métodos são funções que pertencem a uma classe. Objetos que pertencem a uma classe podem usar métodos daquela classe.

Há duas versões de Python: Python 2 e Python 3. Nós usaremos Python 3. Esta versão conserta problemas de Python 2 e é incompatível em alguns aspectos com Python 2. Muitos códigos já foram desenvolvidos em Python 2 (é uma versão mais antiga), mas muitos códigos já foram e estão sendo desenvolvidos em Python 3.

Python pode ser executado em uma linha por vez em um interpretador interativo. É como se usasse a linha de comando de Shell (que estudamos nas duas primeiras aulas/ capítulos), mas agora com a linguagem Python. Para executar o interpretador, execute o seguinte código no seu terminal:

$ python3

Nota: '$' indica o prompt de comando. Lembre-se do Unix 1 que cada computador tem seu próprio prompt!

Primeiros comandos em Python:

>>> print("Olá, turma 2022!")

Olá, turma 2022!Nota:

print()

- O mesmo código acima é digitado em um arquivo usando um editor de texto.

- Scripts em Python são sempre salvos em arquivos cujos nomes têm a extensão '.py' (o nome do arquivo termina com '.py').

- Poderíamos executar o código

ola.py

Conteúdos do arquivo:

print("Olá, turma 2022!")Digitar o comando python3 seguido do nome do script faz com que Python execute o código. Lembre-se que nós vimos que podemos também executar o código de forma interativa executando apenas python3 (ou python) na linha de comando.

Execute o script desta forma (% representa o prompt):

% python3 ola.py Este procedimento gera o seguinte resultado no terminal:

print("Olá, turma 2022!")Se você tornar script em um executável, você pode executá-lo sem precisar digitar python3 antes. Use o comando chmod para alterar as permissões do script desta forma:

chmod +x ola.py

Você pode verificar as permissões assim:

% ls -l ola.py

-rwxr-xr-x 1 sprochnik staff 60 Oct 16 14:29 ola.py

Os primiros 10 caracteres que ver na tela possuem significados especiais. O primeiro (-) diz a você qual tipo de arquivo ola.py é. - significa um arquivo normal, 'd' um diretório, '1' um link. Os próximos nove caracteres aparecem em três sets de três. O primeiro set se refere às suas permissões, o segundo as permissões do grupo, e o último de quaisquer outros. Cada set de trÊs caracteres mostra em ordem 'rwx' para leitura, escrita, execução. Se alguém não tem uma permissão, um - é mostrado ao invés de uma letra. Os três caracteres 'x' significam que qualquer um pode executar ou rodar o script.

Nós também precisamos adicionar uma linha no começo do script que pede para o python3 interpretar o script. Essa linha começa com #, então aparece como um comentário para o python. O '!' é importante como o espaço entre env e python3. O programa /usr/bin/env procura por onde python3 está instalado e roda o script com python3. Os detalhes podem parecer um pouco complexos, mas você pode apenas copiar e colar essa linha 'mágica'.

Esse arquivo ola.py agora se parece com isso

#!/usr/bin/env python3

print("Olá, turma 2022!")Agora você pode simplesmente digitar o símbolo para o diretório atual . seguido por um / e o nome do script para rodá-lo. Como isso:

% ./ola.py

Olá, turma 2022!

Um nome de variável em Python é o nome usado para identificar uma variável, função, classe, módulo ou outro objeto. Um nome de variável inicia com uma letra, de A a Z ou de a a z, ou então com um travessão (_), seguido de zero ou mais letras, travessões e dígitos (0 a 9).

Python não permite caracteres como @, $ e % dentro do nome de variável. Python é uma linguagem "sensível a minúsculas e maiúsculas" (muitas vezes referido com o anglicismo "case sentitive"). Portanto, seq_id e seq_ID são dois nomes diferentes de variável em Python.

- A primeira letra deve ser minúscula, exceto em nomes de classes. Classes devem começar com letra maiúscula (p.e.

Seq). - Private variable names begin with an underscore (ex.

_private). - Strong private variable names begin with two underscores (ex.

__private). - Nomes especiais de variável definidas pela linguagem começam e terminam com dois travessões (p.e.

__special__).

Selecionar bons nomes de variável para objetos que você nomeia é muito importante. Não chame suas variáveis de item ou minha_lista ou dados ou var, exceto em casos que você esteja trabalhando com trechos de códigos muito simples (a título de testes) ou fazendo algum gráfico. Não dê x ou y como nome de variáveis. Todos estes nomes não são descritivos para o tipo de informação encontrado naquela variável ou objeto.

Uma escolha ainda pior é dar nomes de variáveis que contêm nomes de genes como sequencias. Por que é uma ideia ruim? Pense no que poderia acontecer se você encher seu carro de combustível em um comércio chamado "posto de gasolina" que vendesse limonada em vez de gasolina ou etanol combustível.

Em Ciência da Computação, os nomes devem sempre descrever de forma acurada os objetos aos quais estejam vinculados. Isso reduz a possibilidade de bugs no seu código, torna muito mais fácil o seu entendimento se você volta ao seis meses depois ou por pessoas com as quais compartilha seu código. Embora pensar em bons nomes para variáveis tome um pouco mais de tempo e esforço, isso prenive problemas no futuro!

A lista a seguir compreende as palavras reservadas de Python. Elas são palavras especiais que já têm um propósito em Python e, portanto, não podem ser usadas como nomes de variáveis.

and exec not

as finally or

assert for pass

break from print

class global raise

continue if return

def import try

del in while

elif is with

else lambda yield

except list hash

Python considera como um bloco de código linhas adjacentes que apresentam o mesmo nível de indentação. Isso mantém organizadas as linhas de código que são executadas de forma conjunta. Espaçamento e/ou indentação incorretos irão causar erros ou podem fazer que seu código seja executado de uma forma que você não espera. Ambientes de Desenvolvimento Interativo (IDEs) e editores de texto podem ajudar a indentar códigos corretamente.

O número de espaços na indentação precisa ser consistente, mas este número não é específico. Todas as linhas de código ou sentenças dentro de um bloco precisa ser identado com o mesmo número. Por exemplo, usando quatro espaços:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

mensagem = '' # cria uma variável vazia

for x in (1,2,3,4,5):

if x > 4:

print("Olá")

mensagem = 'x é grande'

else:

print(x)

mensagem = 'x é pequeno'

print(mensagem)

print('Pronto!')Incluir comentários no seu código é uma prática essencial. Anotar o que uma linha ou bloco de código faz ajudará o programador e os leitores do código. Incluindo você!

Comentários iniciam com o símbolo #. Todos os caracteres depois deste símbolo, até o final da linha, são parte do comentário e serão ignorados pelo interpretador de Python.

A primeira linha de um script começa com #!, um exemplo especial de comentário que tem a função especial no Unix de informar ao Shell como executar o script.

#!/usr/bin/env python3

# este é meu primeiro código

print("Olá, turma 2022!") # esta linha imprema o conteúdo na telaLinhas em branco são importantes para aumentar a legibilidade do código. Você deve separar com uma linha em branco trechos de código que vão juntos, organizando em "parágrafos" de código. Linhas em branco são ignoradas pelo interpretador de Python.

Esta é a sua primeira oportunidade de olhar para variáveis e tipos de dados. Cada tipo será discutido em mais detalhes nas seções subsequentes.

O primeiro conceito a ser considerado é que os tipos de dados de Python podem ser ou não mutáveis. Números literais, strings e tuplas não podem ser alterados. Listas, dicionários e sets podem. Da mesma forma, variáveis individuais também podem ser alteradas. Você pode armazenar dados na memória por meio da atribução de variáveis, o que pode ser feito usando o sinal "=".

Números e strings são dois tipos comuns de dados. Números literais e strings como 5 ou meu nome é são imutáveis. No entanto, seus valores podem ser armazenados em variáveis, as quais podem ser alteradas.

Por exemplo:

contagem_genes = 5

# alterando o valor de contagem_genes

contagem_genes = 10Lembre-se que da seção anterior sobre nomes de variáveis e objetos (e variáveis são objetos em Python).

Diferentes tipos de dados podem ser atribuídos a variáveis, como inteiros (1,2,3), números de ponto flutuante (3.1415) e strings ("texto").

Por exemplo:

contagem = 10 # este é um inteiro

média = 2.531 # este é um número de ponto flutuante

mensagem = "Bem-vindo ao interpretador de Python" # isso é uma string10, 2.531, e "Bem-vindo ao interpretador de Python" são peças de dados singulares (escalares) e cada um é armazenado em sua própria variável.

Coleções de dados podem também ser armazenados em tipos de dados especiais, i.e., tuplas, listas, sets, e dicionários. Você deveria sempre tentar armazenar semelhantes com semelhantes, de forma tal que cada elemento da coleção deveria ser do mesmo tipo de dado, como um valor de expressão de RNA-seq ou uma contagem de quantos exons estão em um gene ou uma sequência de leitura. Para o quê você imagina que isso deve ser?

- Listas são usadas para armazenar coleções de dados ordenados (indexados).

- Listas são mutáveis: o número de elementos em uma lista e o que é armazenado em cada elemento podem ser alterados.

- Listas são delimitadas por colchetes e seus itens separados por vírgula.

[ 'atg' , 'aaa' , 'agg' ]| Índice | Valor |

|---|---|

| 0 | atg |

| 1 | aaa |

| 2 | agg |

A indexação de listas começa em 0

- Tuplas são similares a listas e contêm coleçaões de dados ordenados (indexados).

- Tuplas são imutáveis: você não consegue alterar os valores ou número de elementos

- A tupla é delimitada por parênteses e seus itens são separados por vírgula.

( 'Jan' , 'Fev' , 'Mar' , 'Abr' , 'Mai' , 'Jun' , 'Jul' , 'Ago' , 'Set' , 'Out' , 'Nov' , 'Dez' )| Índice | Valor |

|---|---|

| 0 | Jan |

| 1 | Fev |

| 2 | Mar |

| 3 | Abr |

| 4 | Mai |

| 5 | Jun |

| 6 | Jul |

| 7 | Ago |

| 8 | Set |

| 9 | Out |

| 10 | Nov |

| 11 | Dez |

-

Dicionários são bons para armazenar dados que podem ser representados em uma tabela de duas colunas.

-

Eles armazenam coleções de dados em pares de chave/valor, sem ordenação específica.

-

Um dicionário é delimitado por chaves e conjuntos de Chave/Valor separados por vírgula.

-

Um sinal de dois-pontos é colocado entre cada chave e valor. Vírgulas separam pares de chave:valor.

{ 'TP53' : 'GATGGGATTGGGGTTTTCCCCTCCCATGTGCTCAAGACTGGCGCTAAAAGTTTTGAGCTTCTCAAAAGTC' , 'BRCA1' : 'GTACCTTGATTTCGTATTCTGAGAGGCTGCTGCTTAGCGGTAGCCCCTTGGTTTCCGTGGCAACGGAAAA' }| Chave | Valor |

|---|---|

| TP53 | GATGGGATTGGGGTTTTCCCCTCCCATGTGCTCAAGACTGGCGCTAAAAGTTTTGAGCTTCTCAAAAGTC |

| BRCA1 | GTACCTTGATTTCGTATTCTGAGAGGCTGCTGCTTAGCGGTAGCCCCTTGGTTTCCGTGGCAACGGAAAA |

Parâmetros de linha de comando são colocados após o nome do script ou programa. Antes do primeiro parâmetro e entre parâmetros adicionais há espaçamento.

Os parâmetros permitem ao usuário fornecer informação ao script quando ele está sendo executado. Python armazena cada trecho do comando em uma lista especial chamada sys.argv.

Você precisará importar o módulo chamado sys no início do seu script desta forma:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import sysVamos imaginar que um script é chamado amigos.py. Se você escrever isso na linha de comando:

$ amigos.py Maria CarlosIsso acontece dentro do script:

o nome do script 'amigos.py' e as strings 'Maria' e 'Carlos' aparecem na lista chamada

sys.argv.

Estes são os parâmetros da linha de comando, ou argumentos que queira passar para o script.

sys.argv[0]é o nome do script. Você pode acessar valores dos outros parâmetros pelos seus índices, começando com 1, entãosys.argv[1]contém 'Maria' esys.argv[2]contém 'Carlos'. Você acessa elementos em uma lista adicionando colchetes e o ínidce numérico depois do nome da lista.

Se você quisesse imprimir uma mensagem dizendo que estas duas pessoas são amigas, você poderia escrever um código como este

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import sys

friend1 = sys.argv[1] # get first command line parameter

friend2 = sys.argv[2] # get second command line parameter

# now print a message to the screen

print(friend1,'and',friend2,'are friends')A vantagem de obter input do usuário da linha de comando é que você pode escrever um script que é genérico. Ele pode imprimir uma mensagem com qualquer input que o usuário fornecer. Isso o torna flexível. O usuário também fornece todos os dados que o script precisa na linha de comando de forma que o script não precisa pedir ao usuário para inserir o nome e esperar até que o usuário o faça. O script pode rodar por conta própria sem mais interações do usuário. Isso permite que o usuário trabalhe em outra coisa. Muito prático!

Você tem um identificador no seu código chamado dados. Isso representa uma string, uma lista ou um dicionário? Python tem algumas funções que ajudam a descobrir isso.

| Função | Descrição |

|---|---|

type(dados) |

diz a qual classe seu objeto pertence |

dir(dados) |

diz quais métodos estão disponíveis para o seu objeto |

id(dados) |

diz qual o identificador único do seu objeto |

Nós cobriremos dir() em mais detalhes mais adiante.

>>> data = [2,4,6]

>>> type(data)

<class 'list'>

>>> data = 5

>>> type(data)

<class 'int'>

>>> id(data)

44990666544 Um operador em uma linguagem de programação é um símbolo que faz o cumpridor ou intérprete para performar operações matemáticas, relativas ou lógicas e produzir um resultado. Aqui explicaremos o conceito de operadores.

Em Python nós podemos escrever declarações que performam cálculos matemáticos. Para fazer isso nós precisamos usar operadores que são específicos para este propósito. Aqui estão operadores aritméticos:

| Operador | Descrição | Exemplo | Resultado |

|---|---|---|---|

+ |

Adição | 3+2 |

5 |

- |

Subtração | 3-2 |

1 |

* |

Multiplicação | 3*2 |

6 |

/ |

Divisão | 3/2 |

1.5 |

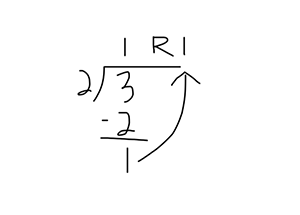

% |

Módulo (divide o operador da esquerda pelo da direita e retorna o lembrete) | 3%2 |

1 |

** |

Expoente | 3**2 |

9 |

// |

Divisão de piso (resultado é o quociente com os dígitos depois do ponto removidos). | 3//2 -11//3 |

1 -4 |

Módulo

Exemplos de piso

>>> 3/2

1.5

>>> 3//2

1

>>> -11/3

-3.6666666666666665

>>> -11//3

-4

>>> 11/3

3.6666666666666665

>>> 11//3

3Nós usamos operadores de atribuição para atribuir valores para variáveis. Você tem usado = como operador de atribuição. aqui estão outros:

| Operador | Equivalente a | Exemplo | resultado assume o valor |

|---|---|---|---|

= |

a = 3 |

result = 3 |

3 |

+= |

result = result + 2 |

result = 3 ; result += 2 |

5 |

-= |

result = result - 2 |

result = 3 ; result -= 2 |

1 |

*= |

result = result * 2 |

result = 3 ; result *= 2 |

6 |

/= |

result = result / 2 |

result = 3 ; result /= 2 |

1.5 |

%= |

result = result % 2 |

result = 3 ; result %= 2 |

1 |

**= |

result = result ** 2 |

result = 3 ; result **= 2 |

9 |

//= |

result = result // 2 |

result = 3 ; result //= 3 |

1 |

Estes operadores comparam dois valores e retornam verdadeiro ou falso.

| Operador | Descrição | Exemplo | Resultado |

|---|---|---|---|

== |

equal to | 3 == 2 |

Falso |

!= |

not equal | 3 != 2 |

Verdadeiro |

> |

greater than | 3 > 2 |

Verdadeiro |

< |

less than | 3 < 2 |

Falso |

>= |

greater than or equal | 3 >= 2 |

Verdadeiro |

<= |

less than or equal | 3 <= 2 |

Falso |

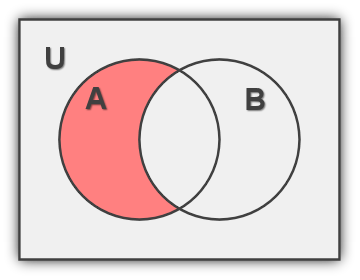

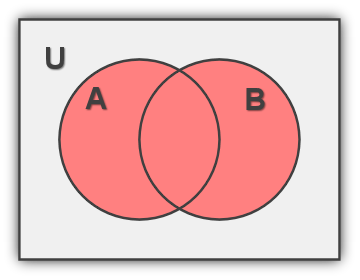

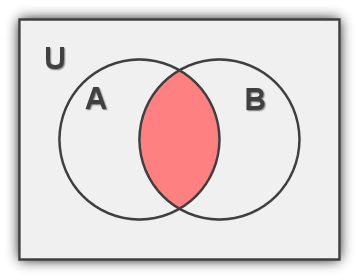

Operadores lógicos permitem combinar dois ou mais conjuntos de comparações. Você pode combinar os resultados de diferentes formas. Por exemplo você pode 1) querer que todos as declarações sejam verdade, 2) que apenas uma declaração precise ser verdadeira, ou 3) que a declaração precise ser falsa.

| Operador | Descrição | Exemplo | Resultado |

|---|---|---|---|

and |

Verdadeiro se o operador da esquerda e o da direita forem verdade | 3>=2 and 2<3 |

Verdadeiro |

or |

Verdadeiro se o operador da esquerda ou o da direita forem verdade | 3==2 or 2<3 |

Falso |

not |

Inverte o status lógico | not False |

Verdadeiro |

Você pode testar para ver se o valor é incluído em uma string, tupla ou lista. Você pode também testar que o valor não está incluso na string, tupla ou lista.

| Operador | Descrição |

|---|---|

in |

Verdadeiro se o valor é incluso em uma lista, tupla ou string |

not in |

Verdadeiro se o valor é ausente em uma lista, tupla ou string |

Por Exemplo:

>>> dna = 'GTACCTTGATTTCGTATTCTGAGAGGCTGCTGCTTAGCGGTAGCCCCTTGGTTTCCGTGGCAACGGAAAA'

>>> 'TCT' in dna

True

>>>

>>> 'ATG' in dna

False

>>> 'ATG' not in dna

True

>>> codons = [ 'atg' , 'aaa' , 'agg' ]

>>> 'atg' in codons

True

>>> 'ttt' in codons

FalseOperadores são listados em ordem de precedência. Os maiores listados primeiro. Nem todos operadores listados aqui são mencionados acima.

| Operador | Descrição |

|---|---|

** |

Exponenciação (Eleva o poder) |

~ + - |

Complemento, unário mais e menos (nomes de métodos que os dois últimos são +@ e -@) |

* / % // |

Multiplica, divide, módulo e divisão de piso |

+ - |

Adição e subtração |

>> << |

Deslocamento parte por parte de direita e esquerda |

& |

Deslocamento 'AND' |

^ | |

Bitwise exclusivo 'OR' e regular 'OR' |

<= < > >= |

Operadores de comparação |

<> == != |

Operadores de igualdade |

= %= /= //= -= += *= **= |

Operadores de atribuição |

is |

Operadores de identidade |

is not |

Operador de não identidade |

in |

Operador de filiação |

not in |

Operador de filiação negativa |

not or and |

Operadores lógicos |

Nota: Saiba mais a respeito bitwise operators.

Vamos voltar um pouco... O que é verdade?

Tudo é verdade, exceto por:

| expressão | VERDADEIRO/FALSO |

|---|---|

0 |

FALSO |

None |

FALSO |

False |

FALSO |

'' (string vazia) |

FALSO |

[] (lista vazia) |

FALSO |

() (tupla vazia) |

FALSO |

{} (dicionário vazio) |

FALSO |

O que significa que estes são verdade:

| expressão | VERDADEIRO/FALSO |

|---|---|

'0' |

VERDADEIRO |

'None' |

VERDADEIRO |

'False' |

VERDADEIRO |

'True' |

VERDADEIRO |

' ' (string de um espaço vazio) |

VERDADEIRO |

bool() é uma função que testará se um valor é verdade.

>>> bool(True)

True

>>> bool('True')

True

>>>

>>>

>>> bool(False)

False

>>> bool('False')

True

>>>

>>>

>>> bool(0)

False

>>> bool('0')

True

>>>

>>>

>>> bool('')

False

>>> bool(' ')

True

>>>

>>>

>>> bool(())

False

>>> bool([])

False

>>> bool({})

FalseDeclarações de controle são usadas para direcionar o fluxo do seu código e criar oportunidade para tomada de decisão. Os fundamentos das declarações de controle são construindo a verdade.

- Use a declaração

ifpara testar a verdade e executar linhas do código caso seja verdade. - Quando a expressão avalia como verdade cada uma das declarações recuadas abaixo da declaração

if, também conhecidas como o bloco de declarações aninhadas, serão executadas.

if

expressão if :

declaração

declaraçãoPor Exemplo:

dna = 'GTACCTTGATTTCGTATTCTGAGAGGCTGCTGCTTAGCGGTAGCCCCTTGGTTTCCGTGGCAACGGAAAA'

if 'AGC' in dna:

print('found AGC in your dna sequence')Returns:

found AGC in your dna sequence

else

- A porção

ifda declaração if/else statement se comporta como antes. - O primeiro bloco recuado é executado se a condição é verdadeira. .

- Se a condição for falsa, o segundo bloco else recuado é executado.

dna = 'GTACCTTGATTTCGTATTCTGAGAGGCTGCTGCTTAGCGGTAGCCCCTTGGTTTCCGTGGCAACGGAAAA'

if 'ATG' in dna:

print('found ATG in your dna sequence')

else:

print('did not find ATG in your dna sequence')Returns:

did not find ATG in your dna sequence

- A condição

ifé testada como antes, e o bloco recuado é executado caso a condição for verdadeira. - Se for falsa, o bloco recuado seguindo o

elifé executado se a primeira condiçãoeliffor verdadeira. - Quaisquer condições restantes

elifserão testadas em ordem até que uma verdadeira for encontrada. Se nenhuma for, o bloco recuadoelseé executado.

count = 60

if count < 0:

message = "is less than 0"

print(count, message)

elif count < 50:

message = "is less than 50"

print (count, message)

elif count > 50:

message = "is greater than 50"

print (count, message)

else:

message = "must be 50"

print(count, message)Returns:

60 is greater than 50

Vamos mudar a contagem para 20, qual declaração será executada?

count = 20

if count < 0:

message = "is less than 0"

print(count, message)

elif count < 50:

message = "is less than 50"

print (count, message)

elif count > 50:

message = "is greater than 50"

print (count, message)

else:

message = "must be 50"

print(count, message)Returns:

20 is less than 50

O que acontece quando a contagem é 50?

count = 50

if count < 0:

message = "is less than 0"

print(count, message)

elif count < 50:

message = "is less than 50"

print (count, message)

elif count > 50:

message = "is greater than 50"

print (count, message)

else:

message = "must be 50"

print(count, message)Returns:

50 must be 50

Python reconhece 3 tipos de números: inteiros, números de ponto flutuante e números complexos.

- Conhecidos como int

- Um int pode ser positivo ou negativo

- e não contém um ponto decimal ou expoente.

- Conhecido como float

- Um ponto flutuante pode ser positivo ou negativo

- E contém um ponto decimal (

4.875) ou expoente (4.2e-12)

- conhecido como complex

- está na forma de a+bi onde bi é uma parte imaginária.

As vezes um tipo de número precisa ser mudado por outro para a função poder trabalhar. Aqui está a lista de funções para converter tipos de números:

| função | Descrição |

|---|---|

int(x) |

para converter x para um inteiro simples |

float(x) |

para converter x para um número de ponto flutuante |

complex(x) |

para converter x para um número complexo com parte real x e parte imaginária zero |

complex(x, y) |

para converter x e y para um número complexo com parte real x e parte imaginária y |

>>> int(2.3)

2

>>> float(2)

2.0

>>> complex(2.3)

(2.3+0j)

>>> complex(2.3,2)

(2.3+2j)Aqui está a lista de funções que usam números como argumentos. Elas são úteis como arredondamento.

| função | Descrição |

|---|---|

abs(x) |

O valor absoluto de x: a distância (positiva) entre x e zero. |

round(x [,n]) |

x arredondado para n dígitos do ponto decimal. round() arredonda para um inteiro se o valor é exatamente entre dois inteiros, então round(0.5) é 0 e round(-0.5) é 0. round(1.5) é 2. Arredondar para um número fixo de lugares decimais pode fornecer resultados imprevisíveis. |

max(x1, x2,...) |

O último argumento é retornado |

min(x1, x2,...) |

O menor argumento é retornado |

>>> abs(2.3)

2.3

>>> abs(-2.9)

2.9

>>> round(2.3)

2

>>> round(2.5)

2

>>> round(2.9)

3

>>> round(-2.9)

-3

>>> round(-2.3)

-2

>>> round(-2.009,2)

-2.01

>>> round(2.675, 2) # note this rounds down

2.67

>>> max(4,-5,5,1,11)

11

>>> min(4,-5,5,1,11)

-5Muitas funções numéricas não são construídas dentro da central do Python e precisam ser importadas para dentro do script se quisermos usá-las. Para incluir elas, no topo do script digite:

import math

Estas próximas funções são encontradas no módulo matemático e precisam ser importadas. Para usá-las, preceda a função com o nome do módulo, i.e, math.ceil(15.5)

| math.function | Descrição |

|---|---|

math.ceil(x) |

retorna o menor inteiro maior ou igual que x |

math.floor(x) |

retorna o maior inteiro menor ou igual que x. |

math.exp(x) |

O exponencial de x: ex é retornado |

math.log(x) |

O logarítmo natural de x, para x > 0 é retornado |

math.log10(x) |

O logarítmo de base 10 de x para x > 0 é retornado |

math.modf(x) |

As partes fracionárias e inteiras de x são retornadas em uma tupla de dois itens |

math.pow(x, y) |

O valor de x criado pelo poder y é retornado |

math.sqrt(x) |

Retorna a raíz quadrada de x para x >= 0 |

>>> import math

>>>

>>> math.ceil(2.3)

3

>>> math.ceil(2.9)

3

>>> math.ceil(-2.9)

-2

>>> math.floor(2.3)

2

>>> math.floor(2.9)

2

>>> math.floor(-2.9)

-3

>>> math.exp(2.3)

9.974182454814718

>>> math.exp(2.9)

18.17414536944306

>>> math.exp(-2.9)

0.05502322005640723

>>>

>>> math.log(2.3)

0.8329091229351039

>>> math.log(2.9)

1.0647107369924282

>>> math.log(-2.9)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

ValueError: math domain error

>>>

>>> math.log10(2.3)

0.36172783601759284

>>> math.log10(2.9)

0.4623979978989561

>>>

>>> math.modf(2.3)

(0.2999999999999998, 2.0)

>>>

>>> math.pow(2.3,1)

2.3

>>> math.pow(2.3,2)

5.289999999999999

>>> math.pow(-2.3,2)

5.289999999999999

>>> math.pow(2.3,-2)

0.18903591682419663

>>>

>>> math.sqrt(25)

5.0

>>> math.sqrt(2.3)

1.51657508881031

>>> math.sqrt(2.9)

1.70293863659264Algumas vezes, é necessário comparar dois números e descobrir se o primeiro é menor, igual ou maior que o segundo.

A simples função cmp(x,y) não é disponível em Python 3.

Use este idioma ao invés:

cmp = (x>y)-(x<y)Ele retorna três diferentes valores dependendo do x e do y

-

se x<y, o -1 é retornado

-

se x>y, o 1 é retornado

-

x == y, o 0 é retornado

Na próxima seção, nós iremos aprender sobre as strings, tuplas, e listas. Todos estes são exemplos de sequências em python. uma sequência de caracteres 'ACGTGA', uma tupla (0.23, 9.74, -8.17, 3.24, 0.16), e uma lista ['dog', 'cat', 'bird'] são sequências de diferentes tipos de dados. Veremos mais detalhes em breve.

Em Python, um tipo de objeto consegue operações que pertencem àquele tipo. Sequências tem operações sequenciais então as strings podem também usar operações sequenciais. Strings também possuem suas próprias operações específicas.

Você pode perguntar qual a extensão de qualquer sequência

>>>len('ACGTGA') # extensão de uma string

6

>>>len( (0.23, 9.74, -8.17, 3.24, 0.16) ) # extensão de uma tupla, precisa de dois parênteses (( ))

5

>>>len(['dog', 'cat', 'bird']) # extensão de uma lista

3Você pode também usar funções de strings específicas, mas não em listas e vice versa. Nós vamos aprender mais sobre isso posteriormente. rstrip() é um método de string ou função. Você obtém um erro se você tentar usar isso em uma lista.

>>> 'ACGTGA'.rstrip('A')

'ACGTG'

>>> ['dog', 'cat', 'bird'].rstrip()

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

AttributeError: 'list' object has no attribute 'rstrip'Como descobrir quais funções servem com um objeto? Existe uma função prática dir(). Como um exemplo quais funções você pode acionar em sua string 'ACGTGA'?

>>> dir('ACGTGA')

['__add__', '__class__', '__contains__', '__delattr__', '__dir__', '__doc__', '__eq__', '__format__', '__ge__', '__getattribute__', '__getitem__', '__getnewargs__', '__gt__', '__hash__', '__init__', '__init_subclass__', '__iter__', '__le__', '__len__', '__lt__', '__mod__', '__mul__', '__ne__', '__new__', '__reduce__', '__reduce_ex__', '__repr__', '__rmod__', '__rmul__', '__setattr__', '__sizeof__', '__str__', '__subclasshook__', 'capitalize', 'casefold', 'center', 'count', 'encode', 'endswith', 'expandtabs', 'find', 'format', 'format_map', 'index', 'isalnum', 'isalpha', 'isdecimal', 'isdigit', 'isidentifier', 'islower', 'isnumeric', 'isprintable', 'isspace', 'istitle', 'isupper', 'join', 'ljust', 'lower', 'lstrip', 'maketrans', 'partition', 'replace', 'rfind', 'rindex', 'rjust', 'rpartition', 'rsplit', 'rstrip', 'split', 'splitlines', 'startswith', 'strip', 'swapcase', 'title', 'translate', 'upper', 'zfill']dir() irá retornar todos os atributos de um objeto, dentre eles estão funções. Tecnicamente, funções pertencentes a uma classe específica (tipo de objeto) são chamadas de métodos.

Você pode chamar dir() em qualquer objeto, mais comumente, você usará isso na esfera interativa do Python.

- Uma string é uma série de caracteres começando e terminando com marcas de aspas únicas ou duplas.

- Strings são um exemplo de uma sequência de Python. Uma sequência é definida como um grupo ordenado posicionalmente. Isso significa que cada elemento no grupo tem uma posição, começando com zero, i.e. 0,1,2,3 e assim até você chegar no final da string.

- Única (')

- Dupla (")

- Tripla (''' or """)

Notas sobre as aspas:

- Aspas únicas e duplas são equivalentes.

- O nome de uma variável dentro das sentenças é apenas o identificador da string, não o valor armazenado dentro da variável.

format()é útil para interpolação de variáveis em python - Sentenças triplas (únicas ou dobradas) são usadas antes e depois de uma string que abrange múltiplas linhas.

Uso de exemplos das aspas:

palavra = 'word'

sentença = "This is a sentence."

parágrafo = """This is a paragraph. Isso é feito de múltiplas linhas e sentenças.

E assim vai.

"""Nós vimos exemplos de print() antes. Vamos conversar sobre isso um pouco mais. print() é uma função que assume um ou mais argumentos separados por vírgulas.

Vamos usar a função print() para imprimir uma string.

>>>print("ATG")

ATGVamos atribuir uma string a uma variável e imprimir a variável.

>>>dna = 'ATG'

ATG

>>> print(dna)

ATGO que acontece se nós colocarmos a variável nas sentenças?

>>>dna = 'ATG'

ATG

>>> print("dna")

dnaA string literal 'dna' é impressa na tela, não os conteúdos 'ATG'

Vamos ver o que acontece quando nós demos print() em duas strings literais como argumentos.

>>> print("ATG","GGTCTAC")

ATG GGTCTACNós conseguimos as duas strings literais impressas na tela separadas por um espaço

E se vocÊ não quiser suas strings separadas por um espaço? use o operador concatenação para concatenar as duas strings antes ou dentro da função print().

>>> print("ATG"+"GGTCTAC")

ATGGGTCTAC

>>> combined_string = "ATG"+"GGTCTAC"

ATGGGTCTAC

>>> print(combined_string)

ATGGGTCTACNós conseguimos duas strings impressas na tela sem ser separadas por um espaço. Você pode também usar isso

>>> print('ATG','GGTCTAC',sep='')

ATGGGTCTACAgora, vamos imprimir uma variável e uma string literal.

>>>dna = 'ATG'

ATG

>>> print(dna,'GGTCTAC')

ATG GGTCTACNós conseguimos o valor da variável e a string literal impressa na tela separada por um espaço

Como poderíamos imprimir os dois sem um espaço?

>>>dna = 'ATG'

ATG

>>> print(dna + 'GGTCTAC')

ATGGGTCTACAlgo para se pensar sobre: valores de variáveis são variáveis. Em outras palavras, eles são mutáveis e alteráveis.

>>>dna = 'ATG'

ATG

>>> print(dna)

ATG

>>>dna = 'TTT'

TTT

>>> print(dna)

TTTO novo valor da variável 'dna' é impresso no visor quando

dnaé um argumento para a funçãoprint().

Vamos olhar os erros típicos que você encontrará quando usar a função print().

O que acontecerá se você esquecer de fechar suas sentenças?

>>> print("GGTCTAC)

File "<stdin>", line 1

print("GGTCTAC)

^

SyntaxError: EOL while scanning string literal

Nós obtemos um'SyntaxError' se a sentença de encerramento não for usada.

O que acontecerá se você se esquecer de incluir uma string que você quer imprimir nas sentenças?

>>> print(GGTCTAC)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

NameError: name 'GGTCTAC' is not definedNós obtemos um 'NameError' quando a string literal não for inclusa nas sentenças porque o Python está procurando uma variável com o nome GGTCTAC

>>> print "boo"

File "<stdin>", line 1

print "boo"

^

SyntaxError: Missing parentheses in call to 'print'Em python2, o comando era print, mas isso mudou para print() em python3, então não se esqueça dos parênteses!

Como você incluiria uma nova linha, retorno de transporte, ou tab em sua string?

| Caractere de escape | Descrição |

|---|---|

| \n | Nova linha |

| \r | Retorno de transporte |

| \t | Tab |

Vamos incluir alguns caracteres de escape em suas strings e funções print().

>>> string_with_newline = 'this sting has a new line\nthis is the second line'

>>> print(string_with_newline)

this sting has a new line

this is the second lineNós imprimimos uma nova linha na tela

print() adiciona espaços entre argumentos e uma nova linha ao final. Você pode mudar isso com sep= e end=. Aqui está um exemplo:

print('one line', 'second line' , 'third line', sep='\n', end = '')

Uma forma mais limpa para fazer isso é expressar uma string de múltiplas linhas inclusa em aspas triplas (""").

>>> print("""this string has a new line

... this is the second line""")

this string has a new line

this is the second lineVamos imprimir um caractere tab (\t).

>>> line = "value1\tvalue2\tvalue3"

>>> print(line)

value1 value2 value3Nós obtemos as três palavras separadas por caracteres tab. Um formato comum para dados é separar colunas com tabs como isso.

Você pode adicionar uma barra invertida antes de qualquer caractere para forçar de ser impresso como um literal. Isso é chamado 'escaping'. Só é realmente útil para imprimir sentenças literais ' and "

>>> print('this is a \'word\'') # if you want to print a ' inside '...'

this is a 'word'

>>> print("this is a 'word'") # maybe clearer to print a ' inside "..."

this is a 'word'Em ambos os casos a sentença atual única é impressa na tela

Se você quiser todos caracteres em sua string para permanecer exatamente como são, declare sua string uma string crua literal com 'r' antes da primeira sentença. Isso parece feio, mas funciona.

>>> line = r"value1\tvalue2\tvalue3"

>>> print(line)

value1\tvalue2\tvalue3Nossos caracteres de escape '\t' declare como nós digitamos, eles não são convertidos para caracteres tab de fato.

Para concatenar strings use o operador de concatenação '+'

>>> promoter= 'TATAAA'

>>> upstream = 'TAGCTA'

>>> downstream = 'ATCATAAT'

>>> dna = upstream + promoter + downstream

>>> print(dna)

TAGCTATATAAAATCATAATO operador de concatenação pode ser usado para combinar strings. A nova combinação de strings pode ser armazenada em uma variável.

O que acontece se você usar + com números (estes são inteiros ou ints)?

>>> 4+3

7Para strings, + concatena; para inteiros, + soma.

Você precisa converter os números para strings antes de poder concatená-las

>>> str(4) + str(3)

'43'Use a função len() para calcular a extensão de uma string. Essa função assume a sequência como um argumento e retorna uma int

>>> print(dna)

TAGCTATATAAAATCATAAT

>>> len(dna)

20A extensão de uma string, incluindo espaços, é calculada e apresentada.

O valor que len() retorna pode ser armazenado em uma variável.

>>> dna_length = len(dna)

>>> print(dna_length)

20Você pode misturar strings e ints em print(), mas não em concatenação.

>>> print("The lenth of the DNA sequence:" , dna , "is" , dna_length)

The lenth of the DNA sequence: TAGCTATATAAAATCATAAT is 20Alterando o caso da string é um pouco distinto do que você pode esperar inicialmente. Por exemplo, para diminuir uma string precisamos utilizar um método. Um método é uma função específica para um objeto. Quando nós assumimos uma string a uma variável estamos criando uma instância de um objeto de string. Esse objeto tem uma série de métodos que funcionarão nos dados que estão armazenados no objeto. Lembre-se que dir() irá te dizer todos os métodos que estão disponíveis para um objeto. A função lower() é um método de string.

Vamos criar um novo objeto de string.

dna = "ATGCTTG"Parece familiar?

Agora que nós temos um objeto de string nós podemos usar os métodos de string. A forma que você utiliza um método consiste em inserir um '.' entre o objeto e o nome do método.

>>> dna = "ATGCTTG"

>>> dna.lower()

'atgcttg'o método lower() retorna os conteúdos armazenados na variável 'dna' em letra minúscula.

Os conteúdos da variável 'dna' não se alteraram. Strings são imutáveis. Se você quiser manter a versão minúscula de uma string, armazene ela em uma nova variável.

>>> print(dna)

ATGCTTG

>>> dna_lowercase = dna.lower()

>>> print(dna)

ATGCTTG

>>> print(dna_lowercase)

atgcttgO método de string pode ser guardado dentro de outras funções.

>>> dna = "ATGCTTG"

>>> print(dna.lower())

atgcttgOs conteúdos de 'dna' são transformados em minúsculos e trasnportados para a função

print().

Se você tentar usar um método de string em um objeto que não é uma string você receberá um erro.

>>> nt_count = 6

>>> dna_lc = nt_count.lower()

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

AttributeError: 'int' object has no attribute 'lower'Você obtém um AttributeError quando você usa um método em um tipo de objeto incorreto. Nós recebemos que o objeto int (um int é retornado por

len()) não tem uma função chamada inferior.

Vamos tornar uma string maiúscula agora.

>>> dna = 'attgct'

>>> dna.upper()

'ATTGCT'

>>> print(dna)

attgctOs conteúdos de uma variável 'dna' são retornados em maiúsculo. Os conteúdos de 'dna' não foram alterados.

O índice posicional de uma string exata em uma string maior pode ser encontrado e retornado com o método de string

find(). Uma string exata é dada como um argumento e o índice de sua primeira ocorrência é retornado. -1 é retornado se nada for encontrado.

>>> dna = 'ATTAAAGGGCCC'

>>> dna.find('T')

1

>>> dna.find('N')

-1O subtermo 'T' é encontrado pela primeira vez no índice 1 na string 'dna' então 1 é retornado. O subtermo 'N' não foi encontrado, então -1 é retornado.

count(str)retorna o número (como um int) que se encaixa exatamente com a string que encontrou

>>> dna = 'ATGCTGCATT'

>>> dna.count('T')

4O número de vezes que 'T' for encontrado é retornado. A string armazenada em 'dna' não é alterada.

replace(str1,str2) retorna uma nova string com todas as combinações de str1 em uma string substituída com str2.

>>> dna = 'ATGCTGCATT'

>>> dna.replace('T','U')

'AUGCUGCAUU'

>>> print(dna)

ATGCTGCATT

>>> rna = dna.replace('T','U')

>>> print(rna)

AUGCUGCAUUTodos as ocorrências de T são substitupidas por U. A nova string é retornada. A string original não foi de fato alterada. Se você quiser reutilizar a nova string, armazene ela em uma variável.

Partes de uma string podem ser localizadas baseadas na posição e retornadas. Isso é porque uma string é uma sequência. Coordenadas começam em 0. Você adiciona a coordenada em colchetes depois do nome da string.

Você pode chegar a qualquer parte da string com a seguinte sentença [start : end : step].

Essa string 'ATTAAAGGGCCC' é feita da seguinte sequência de caracteres, e posições (começando em zero).

| Posição/Índice | Caractere |

|---|---|

| 0 | A |

| 1 | T |

| 2 | T |

| 3 | A |

| 4 | A |

| 5 | A |

| 6 | G |

| 7 | G |

| 8 | G |

| 9 | C |

| 10 | C |

| 11 | C |

Vamos retornar os 4°, 5° e 6° nucleotídeos. Para isso, nós precisamos começar contando em 0 e lembrando que o python conta os vãos entre cada caractere, começando com zero.

index 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 ...

string A T T A A A G G ...

>>> dna = 'ATTAAAGGGCCC'

>>> sub_dna = dna[3:6]

>>> print(sub_dna)

AAAOs caracteres com índices 3, 4, 5 são retornados. Em outras palavras, todo caractere começando com o índice 3 e acima mas não incluindo, o índice de 6 que retornado.

Vamos retornar os primeiros 6 caracteres.

>>> dna = 'ATTAAAGGGCCC'

>>> sub_dna = dna[0:6]

>>> print(sub_dna)

ATTAAATodo caractere começando no índice 0 e acima mas não incluindo o de índice 6 são retornados. Esse é o mesmo que dna[:6]

Vamos retornar todos os caracteres do índice 6 até o fim da string.

>>> dna = 'ATTAAAGGGCCC'

>>> sub_dna = dna[6:]

>>> print(sub_dna)

GGGCCCQuando o segundo argumento é deixado em branco, todos caracteres do índice 6 e acima são retornados.

Vamos retornar os últimos 3 caracteres.

>>> sub_dna = dna[-3:]

>>> print(sub_dna)

CCCQuando o segundo argumento é deixado em branco e o primeiro argumento é negativo (-X), X caracteres do final da string são retornados.

Não existe função de reverso, você precisa usar uma fatia com patamar -1 e início e fim vazios.

Para uma string, se parece com isso

>>> dna='GATGAA'

>>> dna[::-1]

'AAGTAG'Desde que estes são métodos, se certifique de utilizar na sentença string.method().

| função | Descrição |

|---|---|

s.strip() |

retorna uma string com o espaço em branco removido do começo e fim |

s.isalpha() |

testa se todos caracteres da string são alfabéticos. Retorna verdadeiro ou falso. |

s.isdigit() |

testa se todos caracteres da string são nnuméricos. Retorna verdadeiro ou falso. |

s.startswith('other_string') |

testa se a string começa com a string fornecida como argumento. Retorna verdadeiro ou falso. |

s.endswith('other_string') |

testa se a string termina com a string fornecida como argumento. Retorna verdadeiro ou falso. |

s.split('delim') |

separa a string no delimitador exato fornecido. Retorna a lista de subtermos. Se o argumento é fornecido, a string será separada no espaço em branco. |

s.join(list) |

O oposto de split(). Os elementos de uma lista serão concatenados juntos usando a string armazenada em 's' como um delimitadoras. |

split

split é um método ou forma de partir uma string em um grupo de caracteres. O que é retornado é uma lista de elementos com caracteres que são usados para partir removidos. Iremos através das listas em mais detalhes na próxima sessão. Não se preocupe com isso.

Vamos olhar para essa string:

00000xx000xx000000000000xx0xx00

Vamos separar em 'xx' e obter uma lista dos 0's

O que é o What 's' em s.split(delim) ?

O que é 'delim' em s.split(delim) ?

Vamos tentar isso:

>>> string_to_split='00000xx000xx000000000000xx0xx00'

>>> string_to_split.split('xx')

['00000', '000', '000000000000', '0', '00']

>>> zero_parts = string_to_split.split('xx')

>>> print(zero_parts)

['00000', '000', '000000000000', '0', '00']Nós começamos com uma string e agora temos uma lista com todos os delimitadores removidos

Aqui está outro exemplo. Vamos dividir em tabs para obter uma lista dos números em colunas separadas tab.

>>> input_expr = '4.73\t7.91\t3.65'

>>> expression_values = input_expr.split('\t')

>>> expression_values

['4.73', '7.91', '3.65']join

join é um método ou uma forma de pegar uma lista de elementos, de coisas, e transformar em uma string com algo posto entre cada elemento. A lista será coberta na próxima seção com mais detalhes.

Vamos aplicar em uma lista de Ns list_of_Ns = ['NNNNN', 'NNN', 'N', 'NNNNNNNNNNNNNNN', 'NN'] em 'xx' para obter essa string:

NNNNNxxNNNxxNxxNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNxxNN

O que é o 's' em s.join(list) ?

O que é a 'list' em s.join(list) ?

>>> list_of_Ns = ['NNNNN', 'NNN', 'N', 'NNNNNNNNNNNNNNN', 'NN']

>>> list_of_Ns

['NNNNN', 'NNN', 'N', 'NNNNNNNNNNNNNNN', 'NN']

>>>

>>> string_of_elements_with_xx = 'xx'.join(list_of_Ns)

>>> string_of_elements_with_xx

'NNNNNxxNNNxxNxxNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNxxNN'Nós começamos com uma lista e agora temos todos os elementos em uma string com o delimitador adicionado entre cada elemento.

Vamos pegar uma lista de valores de expressão e criar uma string delimitada tab que abrirá bem em uma planilha com cada valor em sua própria coluna:

>>> expression_values = ['4.73', '7.91', '3.65']

>>>expression_values

['4.73', '7.91', '3.65']

>>> expression_value_string = '\t'.join(expression_values)

>>> expression_value_string

'4.73\t7.91\t3.65'imprima isso em um arquivo e abra ele em Excel, é lindo!!

Strings podem ser formatadas usando a função format(). Bem intuitivo, mas espere até ver os detalhes! Por exemplo, se você quiser incluir strings literais e variáveis em sua declaração de impressão e não quer concatenar ou usar múltiplos argumentos na função print() você pode usar formatação de string.

>>> string = "This sequence: {} is {} nucleotides long and is found in {}."

>>> string.format(dna,dna_len,gene_name)

'This sequence: TGAACATCTAAAAGATGAAGTTT is 23 nucleotides long and is found in Brca1.'

>>> print(string) # string.format() does not alter string

This sequence: {} is {} nucleotides long and is found in {}.

>>> new_string = string.format(dna,dna_len,gene_name)

>>> print(new_string)

This sequence: TGAACATCTAAAAGATGAAGTTT is 23 nucleotides long and is found in Brca1.Nós colocamos juntamente três variáveis e strings literais em uma string única usando a função format(). A string original não é alterada, uma nova string é retornada e incorpora os argumentos. Você pode salvar o valor retornado em uma nova variável. Cada {} é um espaço reservado para a string que precisa ser inserida.

Algo legal sobre format() é que você pode imprimir int e tipos variáveis de string sem converter primeiramente.

Você pode também chamar diretamente format() dentro de uma função print(). Aqui estão dois exemplos

>>> string = "This sequence: {} is {} nucleotides long and is found in {}."

>>> print(string.format(dna,dna_len,gene_name))

This sequence: TGAACATCTAAAAGATGAAGTTT is 23 nucleotides long and is found in Brca1.Ou use a função format() em uma string literal:

>>> print( "This sequence: {} is {} nucleotides long and is found in {}.".format(dna,dna_len,gene_name))

This sequence: TGAACATCTAAAAGATGAAGTTT is 23 nucleotides long and is found in Brca1.Até agora, nós usamos apenas {} para mostrar onde inserir o valor de uma variável em uma string. Você pode adicionar caracteres especiais dentro de {} para mudar a forma que a variável é formatada quando é inserida dentro da string.

Você pode numerar estes, não necessariamente em ordem.

>>> '{0}, {1}, {2}'.format('a', 'b', 'c')

'a, b, c'

>>> '{2}, {1}, {0}'.format('a', 'b', 'c')

'c, b, a'Para mudar o espaçamento das strings e a forma que os números são formatados, você adiciona : e outros caracteres especiais como isso {:>5} para corrigir uma string em um campo de cinco caracteres

Vamos corrigir justificando alguns números.

>>> print( "{:>5}".format(2) )

2

>>> print( "{:>5}".format(20) )

20

>>> print( "{:>5}".format(200) )

200E sobre preencher com zeros? Isso significa que o campo de cinco caracteres será preenchido conforme preciso com zeros a esquerda de quaisquer números que você quer apresentar

>>> print( "{:05}".format(2) )

00002

>>> print( "{:05}".format(20) )

00020Use um < para indicar justificação à esquerda.

>>> print( "{:<5} genes".format(2) )

2 genes

>>> print( "{:<5} genes".format(20) )

20 genes

>>> print( "{:<5} genes".format(200) )

200 genesAlinhamento ao centro é feito com ^ ao invés de > ou <. Você pode também preencher com caracteres sem ser 0. Aqui vamos tentar _ ou sublinhar como em :_^. O símbolo de preencher vai antes do símbolo de alinhamento.

>>> print( "{:_^10}".format(2) )

____2_____

>>> print( "{:_^10}".format(20) )

____20____

>>> print( "{:_^10}".format(200) )

___200____Aqui estão algumas das opções de ALINHAMENTO:

| Opção | Significado | |

|---|---|---|

< |

Força o campo para estar alinhado a esquerda com o espaço disponível (Isso é o padrão para a maioria dos objetos). | |

> |

Força o campo para estar alinhado a direita com o espaço disponível (Isso é o padrão para números). | |

= |

Força o campo para o preenchimento ser posto de pois do sinal (se tiver) mas antes dos dígitos. Isso é usado para imprimir campos na forma ‘+000000120’. Essa opção de alinhamento é apenas válida para tipos numéricos. | |

^ |

Força o campo para ser centralizado com o espaço disponível. |

Aqui está um exemplo

{ : x < 10 s}preencher com

x

justificamento à esquerda<

10um campo com dez caracteressuma string

Tipos comuns

| tipo | descrição |

|---|---|

| b | converte para binário |

| d | inteiro decimal |

| e | expoente, precisão padrão é 6, usa e |

| E | expoente, usa E |

| f | ponto de flutuação, precisão padrão é 6 (também F) |

| g | número genérico, flutua para valores próximos de 0, expoente para outros; também G |

| s | string, tipo padrão (conforme exemplo acima) |

| x | converte para hexadecimal, também X |

| % | converte para % multiplicando por 100 |

Muito pode ser feito com a função format(). Aqui está um último exemplo, mas não a última funcionalidade desta função. vamos circular um número de ponto de flutuação para algumas casas decimais, começando com muitos. (o padrão é 6). Note que a função circula para a casa decimal mais próxima, mas nem sempre exatamente da forma que você espera por conta da forma que os computadores representam decimais com 1s e 0s.

'{:f}'.format(3.141592653589793)

'3.141593'

>>> '{:.4f}'.format(3.141592653589793)

'3.1416'Listas são tipos de dados que armazenam uma coleção de dados.

- Listas são usadas para armazenar uma coleção de dados ordenada e indexada.

- Valores são separados por vírgulas

- Valores são anexados entre colchetes '[]'

- Listas podem crescer e encolher

- Valores são mutáveis

[ 'atg' , 'aaa' , 'agg' ]- Tuplas são usadas para armazenar uma coleção de dados ordenada e indexada

- Valores são separados por vírgulas

- Valores são anexados entre parenteses '()'

- Tuplas NÃO podem crescer ou encolher

- Valores são imutáveis

( 'Jan' , 'Fev' , 'Mar' , 'Abr' , 'Mai' , 'Jun' , 'Jul' , 'Ago' , 'Set' , 'Out' , 'Nov' , 'Dez' )Muitas funções e métodos retornam tuplas como math.modf(x). Essa função retorna as partes fracionais e inteiras de x em uma tupla de dois itens. Aqui não existe motivos para mudar a sequência.

>>> math.modf(2.6)

(0.6000000000000001, 2.0)Para recuperar um valor em uma lista utilize o índice do valor nesse formato list[index]. Isso retornará o valor do índice especificado, começando com 0.

Aqui está uma lista:

>>> codons = [ 'atg' , 'aaa' , 'agg' ]Existem 3 valores com os índices 0, 1, 2

| Índice | Valor |

|---|---|

| 0 | atg |

| 1 | aaa |

| 2 | agg |

Vamos acessar o valor de índice 0. Você vai precisar de um número de índice (0) dentro de colchetes desta forma [0] . Isso vai após o nome da lista (codons)

>>> codons = [ 'atg' , 'aaa' , 'agg' ]

>>> codons[0]

'atg'O valor pode ser salvo em uma variável, e ser usado depois.

>>> codons = [ 'atg' , 'aaa' , 'agg' ]

>>> first_codon = codons[0]

>>> print(first_codon)

atgCada valor pode ser salvo em uma nova variável para usar posteriormente.

Os valores podem ser recuperados e usados diretamente.

>>> codons = [ 'atg' , 'aaa' , 'agg' ]

>>> print(codons[0])

atg

>>> print(codons[1])

aaa

>>> print(codons[2])

aggOs 3 valores são acessados independentemente e impressos imediatamente. Eles não são armazenados em uma variável.

Se você deseja acessar os valores começando pelo fim da lista, use índices negativos.

>>> codons = [ 'atg' , 'aaa' , 'agg' ]

>>> print(codons[-1])

agg

>>> print(codons[-2])

aaaUsar um índice negativo retornará os valores do final da lista. Por exemplo, -1 é o índice do último valor 'agg'. Esse valor também possui um índice de 2.

Valores individuais podem ser alterados usando o valor de índice e o operador de atribuição.

>>> print(codons)

['atg', 'aaa', 'agg']

>>> codons[2] = 'cgc'

>>> print(codons)

['atg', 'aaa', 'cgc']E sobre atribuir um valor para um índice que não existe?

>>> codons[5] = 'aac'

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

IndexError: list assignment index out of rangecodon[5] não existe, e quando tentamos atribuir valor para esse índice ocorre um IndexError. Se você deseja adicionar novos elementos no final da lista use

codons.append('taa')oucodons.extend(list). Veja abaixo mais detalhes.

Isso funciona da mesma forma com as listas como com as strings. Isso é porque ambos são sequências, ou cooleções ordenadas de dados com informação posicional. Lembre-se que Python conta as divisões entre os elementos, começando com 0.

| Índice | Valor |

|---|---|

| 0 | atg |

| 1 | aaa |

| 2 | agg |

| 3 | aac |

| 4 | cgc |

| 5 | acg |

use a syntaxe [start : end : step] para dividir sua sequência python

>>> codons = [ 'atg' , 'aaa' , 'agg' , 'aac' , 'cgc' , 'acg']

>>> print (codons[1:3])

['aaa', 'agg']

>>> print (codons[3:])

['aac', 'cgc', 'acg']

>>> print (codons[:3])

['atg', 'aaa', 'agg']

>>> print (codons[0:3])

['atg', 'aaa', 'agg']

codons[1:3]retorna todo valor começando com o valor de códons[1] até mas não incluindo os códons[3]

codons[3:]retorna todo valor começando com o valor de códons[3] e todos os valores posteriores.

codons[:3]retorna todo valor até mas não incluindo códons[3]

codons[0:3]é o mesmo quecodons[:3]

| Operador | Descrição | Exemplo |

|---|---|---|

+ |

Concatenação | [10, 20, 30] + [40, 50, 60] retorna [10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60] |

* |

Repetição | ['atg'] * 4 retorna ['atg','atg','atg','atg'] |

in |

Filiação | 20 in [10, 20, 30] retorna True |

| Funções | Descrição | Exemplo |

|---|---|---|

len(list) |

retorna o comprimento ou o número de valores em uma lista | len([1,2,3]) retorna 3 |

max(list) |

retorna o valor com o maior ASCII (=último no alfabeto ASCII) | max(['a','A','z']) retorna 'z' |

min(list) |

retorna o valor com o menor ASCII (=primeiro no alfabeto ASCII) | min(['a','A','z']) retorna 'A' |

list(seq) |

converte uma tupla em uma lista | list(('a','A','z')) retorna ['a', 'A', 'z'] |

sorted(list, key=None, reverse=False) |

retorna uma lista organizada baseada na chave fornecida | sorted(['a','A','z']) retorna ['A', 'a', 'z'] |

sorted(list, key=str.lower, reverse=False) |

str.lower() faz com que todos os elementos fiquem minúsculos antes de organizar |

sorted(['a','A','z'],key=str.lower) retorna ['a', 'A', 'z'] |

Lembre-se que métodos são utilizados no seguinte formato list.method().

Para esses exemplos utilize: nums = [1,2,3] e codons = [ 'atg' , 'aaa' , 'agg' ]

| Métodos | Descrição | Exemplo |

|---|---|---|

list.append(obj) |

anexa um objeto no final de uma lista | nums.append(9) ; print(nums) ; retorna [1,2,3,9] |

list.count(obj) |

conta as ocorrências de um objeto em uma lista | nums.count(2) retorna 1 |

list.index(obj) |

retorna o menor índice em que o objeto fornecido é encontrado | nums.index(2) retorna 1 |

list.pop() |

remove e retorna o últio valor de uma lista. A lista é agora um elemento mais curta | nums.pop() retorna 3 |

list.insert(index, obj) |

insere um valor ao índice fornecido. Lembre-se de pensar sobre as divisões entre os elementos | nums.insert(0,100) ; print(nums) retorna [100, 1, 2, 3] |

list.extend(new_list) |

anexa new_list ao final de list |

nums.extend([7, 8]) ; print(nums) retorna [1, 2, 3, 7,8] |

list.pop(index) |

remove e retorna o valor do argumento indexado. A lista é agora um valor mais curta | nums.pop(0) retorna 1 |

list.remove(obj) |

encontra o menor índice do objeto fornecido e remove ele da lista. A lista é agora um elemento mais curta | codons.remove('aaa') ; print(codons) retorna [ 'atg' , 'agg' ] |

list.reverse() |

inverte a ordem da lista | nums.reverse() ; print(nums) retorna [3,2,1] |

list.copy() |

Retorna uma cópia rasa da lista. Rasa vs Deep apenas importa em estruturas de data multidimensionais. | |

list.sort([func]) |

organiza uma lista utilizando a função fornecida. Não retorna uma lista. A lista foi alterada. Uma organização de lista avançada será coberta assim que escrever suas próprias funções for discutido. | codons.sort() ; print(codons) retorna ['aaa', 'agg', 'atg'] |

Tome cuidado em como você faz uma cópia de sua lista

>>> my_list=['a', 'one', 'two']

>>> copy_list=my_list

>>> copy_list.append('1')

>>> print(my_list)

['a', 'one', 'two', '1']

>>> print(copy_list)

['a', 'one', 'two', '1']Não foi o que esperava?! Ambas listas foram alteradas porque nós apenas copiamos um ponteiro para a lista original quando escrevemos

copy_list=my_list.

Vamos copiar a lista utilizando o método copy().

>>> my_list=['a', 'one', 'two']

>>> copy_list=my_list.copy()

>>> copy_list.append('1')

>>> print(my_list)

['a', 'one', 'two']Agora sim, nós obtivemos o esperado desta vez!

Agora que você já viu a função append() nós podemos ir em como construir uma lista valor por vez.

>>> words = []

>>> print(words)

[]

>>> words.append('one')

>>> words.append('two')

>>> print(words)

['one', 'two']Nós começamos com uma lista vazia chamada 'words'. Nós usamos

append()para adicionar o valor 'one' depois o valor 'two'. Finalizamos a lista com dois valores. Você pode adicionar uma lista inteira em outra lista comwords.extend(['three','four','five'])

Todas as codificações pelas quais percorremos até então foram executadas linha por linha. Algumas vezes existem blocos de códigos que queremos executar mais do que uma vez. Loops permitem que façamos isso.

Existem dois tipos de loops:

- while loop

- for loop

O while loop vai continuar a executar um bloco de código enquanto a expressão de teste apresentar Verdadeiro.

while expression:

# estas declarações são executadas sempre que o código entrar em loop

statement1

statement2

more_statements

# código logo abaixo é executado depois que o while loop existir

rest_of_code_goes_here

more_codeA condição é a expressão. O bloco de código while loop é uma coleção de declarações recuadas/indentadas seguindo a expressão.

Código:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

contagem = 0

while contagem < 5:

print("contagem:" , contagem)

contagem+=1

print("Done") Saída:

$ python while.py

contagem: 0

contagem: 1

contagem: 2

contagem: 3

contagem: 4

Done

A condição while foi verdadeira 5 vezes e o bloco de código while foi executado 5 vezes.

- contagem é igual a 0 quando começamos

- 0 é menos que 5 então executamos o bloco while

- contagem é impressa

- contagem é incrementada (contagem = count + 1)

- contagem é agora igual a 1.

- 1 é menor que 5 então executamos o bloco while pela segunda vez.

- isso permanece até que a contagem seja 5.

- 5 não é menor que 5 então nós saímos do bloco while

- A primeira linha seguindo a declaração while é executada, "Done" é impresso

Um loop infinito ocorre quando um condição while é sempre verdadeira. Aqui está um exemplo de um loop infinito.

#!/usr/bin/env python3

contagem = 0

while contagem < 5: # isso é normalmente um bug!!

print("contagem:" , contagem) # esqueça de incrementar contagem no loop!!

print("Done") Saída:

$ python infinite.py

contagem: 0

contagem: 0

contagem: 0

contagem: 0

contagem: 0

contagem: 0

contagem: 0

contagemcontagem: 0

...

...

O que fez com que a condição seja sempre

Verdadeira? A condição que incrementa a contagem está faltando, então sempre será inferior a 5. Para impedir o código de imprimir para sempre utilize ctrl+c. Um comportamento como esse é quase sempre devido a um bug no código.

Uma forma melhor de escrever um loop infinito é com True. Você precisará incluir algo como if ...: break

#!/usr/bin/env python3

contagem=0

while True:

print("contagem:",contagem)

# Provavelmente você precisará adicionar um "if...: break"

# para poder sair do loop infinito

print('Finished the loop')Um for loop é um loop que executa o bloco de códigos for para qualquer membro de uma sequência, por exemplo os elementos de uma lista ou as letras de uma string.

for iterating_variable in sequence:

statement(s)Um exemplo de sequência é uma lista. Vamos usar um for loop com uma lista de palavras.

Código:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

words = ['zero','um','dois','três','quatro']

for word in words:

print(word)Perceba como eu nomeei minhas variáveis, a lista é plural e a variável interativa é singular

Saída:

python3 list_words.py

zero

um

dois

três

quatro

Esse próximo exemplo é utilizando um for loop para interagir em uma string. Lembre-se que uma string é uma sequência como uma lista. Cada caractere possui uma posição. Olhe novamente em "Extraindo uma substring, ou Recortando" na seção Strings para ver outras formas em que strings podem ser tratadas como listas.

Código:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

dna = 'GTACCTTGATTTCGTATTCTGAGAGGCTGCTGCTTAGCGGTAGCCCCTTGGTTTCCGTGGCAACGGAAAA'

for nt in dna:

print(nt)Saída:

$ python3 for_string.py

G

T

A

C

C

T

T

...

...

Essa é uma forma fácil de acessar cada caractere em uma string. É especialmente bom para sequências de DNA.

Outro exemplo de interagir em uma lista de variáveis, estes números de tempo.

Código:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

numbers = [0,1,2,3,4]

for num in numbers:

print(num)Saída:

$ python3 list_numbers.py

0

1

2

3

4

Python tem uma função chamada range() que retornará números que podem ser convertidos em lista.

>>> range(5)

range(0, 5)

>>> list(range(5))

[0, 1, 2, 3, 4]A função range() pode ser utilizada em conjunto com um for loop para interar em um faixa de números. AlcaA faixa (range) também começa com 0 e opera sobre os espaços entre os números.

Código:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

for num in range(5):

print(num)Saída:

$ python list_range.py

0

1

2

3

4

Como pode ver esta é a mesma saída que quando utilizamos a lista

numbers = [0, 1, 2, 3, 4]E esse tem a mesma funcionalidade que um while loop com a condiçãocount = 0;count < 5.

Esse é o while loop equivalente

Código:

count = 0

while count < 5:

print(count)

count+=1Saída:

0

1

2

3

4

As declarações de controle de loop permitem alteração no fluxo normal de execução.

| Declaração de controle | Descrição |

|---|---|

break |

Um loop é terminado quando uma declaração break é executada. Todas as linhas de código após o break, mas dentro do bloco de loop não são executadas. Sem mais interações do loop sendo executadas |

continue |

Uma única interação de uma loop é terminada quando a declaração continue é executada. A próxima interação vai proceder normalmente. |

Código:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

count = 0

while count < 5:

print("count:" , count)

count+=1

if count == 3:

break

print("Done")Saída:

$ python break.py

count: 0

count: 1

count: 2

Done

Quando a contagem é igual a 3, a execução do while loop é terminada, no entanto a condição inicial permanece verdadeira (count < 5).

Código:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

count = 0

while count < 5:

print("count:" , count)

count+=1

if count == 3:

continue

print("line after our continue")

print("Done")Saída:

$ python continue.py

count: 0

line after our continue

count: 1

line after our continue

count: 2

count: 3

line after our continue

count: 4

line after our continue

Done

Quando a contagem é igual a 3 o continue é executado. Isso faz com que todas as linhas contendo o bloco de loop sejam puladas. "Linha após o nosso continue" não é impresso quando a contagem é igual a 3. O próximo loop é executado normalmente.

Um iterável é qualquer tipo de dado que pode ser interado, ou pode ser usado em uma interação. Um interável pode ser transformado em um interador com a função iter(). Isso significa que você pode utilizar a função next().

>>> codons = [ 'atg' , 'aaa' , 'agg' ]

>>> codons_iterator=iter(codons)

>>> next(codons_iterator)

'atg'

>>> next(codons_iterator)

'aaa'

>>> next(codons_iterator)

'agg'

>>> next(codons_iterator)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

StopIterationUm interador permite que você obtenha o próximo elemento no interador até que não existam mais elementos. Se você quer ir através de cada elemento novamente, você precisará redefinir o interador.

Exemplo de utilização de um interador em um for loop:

codons = [ 'atg' , 'aaa' , 'agg' ]

>>> codons_it = iter(codons)

>>> for codon in codons_it :

... print( codon )

...

atg

aaa

aggIsso é bom se você tem uma lista muito larga que você não deseja manter na memória. Um interador permite que você vá através de cada elemento mas sem manter a lista completa na memória. Sem interadores toda a lista permanece na memória.

Compreensão de lista é uma forma de fazer uma lista sem digitar cada elemento. Existem muitas formas de usar compreensão de lista para gerar listas. Alguns são relativamente complexos, mas úteis.

Aqui está um exemplo fácil:

>>> dna_list = ['TAGC', 'ACGTATGC', 'ATG', 'ACGGCTAG']

>>> lengths = [len(dna) for dna in dna_list]

>>> lengths

[4, 8, 3, 8]Isso é como você pode fazer o mesmo com um for loop:

>>> lengths = []

>>> dna_list = ['TAGC', 'ACGTATGC', 'ATG', 'ACGGCTAG']

>>> for dna in dna_list:

... lengths.append(len(dna))

...

>>> lengths

[4, 8, 3, 8]Utilizando condições:

Isso vai apenas retornar o comprimento de um elemento que começa com 'A':

>>> dna_list = ['TAGC', 'ACGTATGC', 'ATG', 'ACGGCTAG']

>>> lengths = [len(dna) for dna in dna_list if dna.startswith('A')]

>>> lengths

[8, 3, 8]Esse gera a seguinte lista: [8, 3, 8]

Aqui está um exemplo de utilização de operadores matemáticos para gerar uma lista:

>>> two_power_list = [2 ** x for x in range(10)]

>>> two_power_list

[1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256, 512]Isso cria uma lista do produto de [2^0 , 2^1, 2^2, 2^3, 2^4, 2^5, 2^6, 2^7, 2^8, 2^9 ]

Dictionaries are another iterable, like a string and list. Unlike strings and lists, dictionaries are not a sequence, or in other words, they are unordered and the position is not important.

Dictionaries are a collection of key/value pairs. In Python, each key is separated from its value by a colon (:), the items are separated by commas, and the whole thing is enclosed in curly braces. An empty dictionary without any items is written with just two curly braces, like this: {}

Each key in a dictionary is unique, while values may not be. The values of a dictionary can be of any type, but the keys must be of an immutable data type such as strings, numbers, or tuples.

Data that is appropriate for dictionaries are two pieces of information that naturally go together, like gene name and sequence.

| Key | Value |

|---|---|

| TP53 | GATGGGATTGGGGTTTTCCCCTCCCATGTGCTCAAGACTGGCGCTAAAAGTTTTGAGCTTCTCAAAAGTC |

| BRCA1 | GTACCTTGATTTCGTATTCTGAGAGGCTGCTGCTTAGCGGTAGCCCCTTGGTTTCCGTGGCAACGGAAAA |

genes = { 'TP53' : 'GATGGGATTGGGGTTTTCCCCTCCCATGTGCTCAAGACTGGCGCTAAAAGTTTTGAGCTTCTCAAAAGTC' , 'BRCA1' : 'GTACCTTGATTTCGTATTCTGAGAGGCTGCTGCTTAGCGGTAGCCCCTTGGTTTCCGTGGCAACGGAAAA' }Breaking up the key/value pairs over multiple lines make them easier to read.

genes = {

'TP53' : 'GATGGGATTGGGGTTTTCCCCTCCCATGTGCTCAAGACTGGCGCTAAAAGTTTTGAGCTTCTCAAAAGTC' ,

'BRCA1' : 'GTACCTTGATTTCGTATTCTGAGAGGCTGCTGCTTAGCGGTAGCCCCTTGGTTTCCGTGGCAACGGAAAA'

}To retrieve a single value in a dictionary use the value's key in this format dict[key]. This will return the value at the specified key.

>>> genes = { 'TP53' : 'GATGGGATTGGGGTTTTCCCCTCCCATGTGCTCAAGACTGGCGCTAAAAGTTTTGAGCTTCTCAAAAGTC' , 'BRCA1' : 'GTACCTTGATTTCGTATTCTGAGAGGCTGCTGCTTAGCGGTAGCCCCTTGGTTTCCGTGGCAACGGAAAA' }

>>>

>>> genes['TP53']

GATGGGATTGGGGTTTTCCCCTCCCATGTGCTCAAGACTGGCGCTAAAAGTTTTGAGCTTCTCAAAAGTCThe sequence of the gene TP53 is stored as a value of the key 'TP53'. We can access the sequence by using the key in this format dict[key]

The value can be accessed and passed directly to a function or stored in a variable.

>>> print(genes['TP53'])

GATGGGATTGGGGTTTTCCCCTCCCATGTGCTCAAGACTGGCGCTAAAAGTTTTGAGCTTCTCAAAAGTC

>>>

>>> seq = genes['TP53']

>>> print(seq)

GATGGGATTGGGGTTTTCCCCTCCCATGTGCTCAAGACTGGCGCTAAAAGTTTTGAGCTTCTCAAAAGTCIndividual values can be changed by using the key and the assignment operator.

>>> genes = { 'TP53' : 'GATGGGATTGGGGTTTTCCCCTCCCATGTGCTCAAGACTGGCGCTAAAAGTTTTGAGCTTCTCAAAAGTC' , 'BRCA1' : 'GTACCTTGATTTCGTATTCTGAGAGGCTGCTGCTTAGCGGTAGCCCCTTGGTTTCCGTGGCAACGGAAAA' }

>>>

>>> print(genes)

{'BRCA1': 'GTACCTTGATTTCGTATTCTGAGAGGCTGCTGCTTAGCGGTAGCCCCTTGGTTTCCGTGGCAACGGAAAA', 'TP53': 'GATGGGATTGGGGTTTTCCCCTCCCATGTGCTCAAGACTGGCGCTAAAAGTTTTGAGCTTCTCAAAAGTC'}

>>>

>>> genes['TP53'] = 'atg'

>>>

>>> print(genes)

{'BRCA1': 'GTACCTTGATTTCGTATTCTGAGAGGCTGCTGCTTAGCGGTAGCCCCTTGGTTTCCGTGGCAACGGAAAA', 'TP53': 'atg'}The contents of the dictionary have changed.

Other assignment operators can also be used to change a value of a dictionary key.

>>> genes = { 'TP53' : 'GATGGGATTGGGGTTTTCCCCTCCCATGTGCTCAAGACTGGCGCTAAAAGTTTTGAGCTTCTCAAAAGTC' , 'BRCA1' : 'GTACCTTGATTTCGTATTCTGAGAGGCTGCTGCTTAGCGGTAGCCCCTTGGTTTCCGTGGCAACGGAAAA' }

>>>

>>> genes['TP53'] += 'TAGAGCCACCGTCCAGGGAGCAGGTAGCTGCTGGGCTCCGGGGACACTTTGCGTTCGGGCTGGGAGCGTG'

>>>

>>> print(genes)

{'BRCA1': 'GTACCTTGATTTCGTATTCTGAGAGGCTGCTGCTTAGCGGTAGCCCCTTGGTTTCCGTGGCAACGGAAAA', 'TP53': 'GATGGGATTGGGGTTTTCCCCTCCCATGTGCTCAAGACTGGCGCTAAAAGTTTTGAGCTTCTCAAAAGTCTAGAGCCACCGTCCAGGGAGCAGGTAGCTGCTGGGCTCCGGGGACACTTTGCGTTCGGGCTGGGAGCGTG'}Here we have used the '+=' concatenation assignment operator. This is equivalent to

genes['TP53'] = genes['TP53'] + 'TAGAGCCACCGTCCAGGGAGCAGGTAGCTGCTGGGCTCCGGGGACACTTTGCGTTCGGGCTGGGAGCGTG'.

Since a dictionary is an iterable object, we can iterate through its contents.

A for loop can be used to retrieve each key of a dictionary one a time:

>>> for gene in genes:

... print(gene)

...

TP53

BRCA1Once you have the key you can retrieve the value:

>>> for gene in genes:

... seq = genes[gene]

... print(gene, seq[0:10])

...

TP53 GATGGGATTG

BRCA1 GTACCTTGATBuilding a dictionary one key/value at a time is akin to what we just saw when we change a key's value. Normally you won't do this. We'll talk about ways to build a dictionary from a file in a later lecture.

>>> genes = {}

>>> print(genes)

{}

>>> genes['Brca1'] = 'GTACCTTGATTTCGTATTCTGAGAGGCTGCTGCTTAGCGGTAGCCCCTTGGTTTCCGTGGCAACGGAAAA'

>>> genes['TP53'] = 'GATGGGATTGGGGTTTTCCCCTCCCATGTGCTCAAGACTGGCGCTAAAAGTTTTGAGCTTCTCAAAAGTC'

>>> print(genes)

{'Brca1': 'GTACCTTGATTTCGTATTCTGAGAGGCTGCTGCTTAGCGGTAGCCCCTTGGTTTCCGTGGCAACGGAAAA', 'TP53': 'GATGGGATTGGGGTTTTCCCCTCCCATGTGCTCAAGACTGGCGCTAAAAGTTTTGAGCTTCTCAAAAGTC'}We start by creating an empty dictionary. Then we add each key/value pair using the same syntax as when we change a value.

dict[key] = new_value

Python generates an error (NameError) if you try to access a key that does not exist.

>>> print(genes['HDAC'])

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

NameError: name 'HDAC' is not defined| Operator | Description |

|---|---|

in |

key in dict returns True if the key exists in the dictionary |

not in |

key not in dict returns True if the key does not exist in the dictionary |

Because Python generates a NameError if you try to use a key that doesn't exist in the dictionary, you need to check whether a key exists before trying to use it.

The best way to check whether a key exists is to use in

>>> gene = 'TP53'

>>> if gene in genes:

... print('found')

...

found

>>>

>>> if gene in genes:

... print(genes[gene])

...

GATGGGATTGGGGTTTTCCCCTCCCATGTGCTCAAGACTGGCGCTAAAAGTTTTGAGCTTCTCAAAAGTC

>>> Now we have all the tools to build a dictionary one key/value using a for loop. This is how you will be building dictionaries more often in real life.

Here we are going to count and store nucleotide counts:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

# create a new empty dictionary

nt_count={}

# loop example from loops lecture

dna = 'GTACCTTGATTTCGTATTCTGAGAGGCTGCTGCTTAGCGGTAGCCCCTTGGTTTCCGTGGCAACGGAAAA'

for nt in dna:

# is this nt in our dictionary?

if nt in nt_count:

# if it is, lets increment our count

previous_count = nt_count[nt]

new_count = previous_count + 1

nt_count[nt] = new_count

else:

# if not, lets add this nt to our dictionary and make count = 1

nt_count[nt] = 1;

print(nt_count){'G': 20, 'T': 21, 'A': 13, 'C': 16}

What is another way we could increment our count?

nt_count={}