Version Summer-2020

Original Author

- Asanka Abeysinghe | Chief Technology Evangelist | WSO2, Inc | [email protected]

Enterprises depend on API-driven strategies to bring about digital transformation. The benefits include increased productivity, simplification, seamless connectivity, and rich experiences through digital channels. Connecting humans, things, applications, systems, and data is a fundamental requirement to become a digitally-driven organization, city, or country. APIs are the digital connectors that act as the glue for various digital assets. As a result, the business and technical architecture moved to API-centric from service-orientation. The primary focus of this paper is to look at the architecture approaches taken by the industry and represent these patterns as generic reference architectures. We identified two centralized reference architectures, i.e., layered and segmented, and we will discuss them in detail.

Digital transformation forced organizations to expose their capabilities in standard and easy-to-access ways. As a result, (managed) APIs became the norm to access business data and functionalities. Every architecture took an API-first approach and was augmented to support the same. Most enterprises followed the layered approach for a while and subsequently moved to segmented architecture with the rise of microservices. This paper focuses on these two centralized API-centric architecture patterns.

Single-tier Architecture: As we discussed earlier, application systems started as being centralized and single-purpose, with user interfaces, business logic, and data bundled together as a single layer. If you have built systems using Cobol and RPG (3G programming languages), you would have experienced how to generate user interfaces (forms) by pointing to a data set and building business logic directly interacting with the record sets and user interface. To run complex logic and data manipulation, business processes had to be scheduled in a queue and were executed sequentially (FIFO). 3G programming languages, ISAM databases, and mainframes were some of the technical elements in the single-tier era.

Two-Tier Architecture: Following the advancements in data storage and data access mechanisms (database management systems xDBMS), data layers were separated from user interfaces and business logic. As a result, two layers were introduced at the design, implementation, runtime, and administration. A new role was introduced to a database administrator (DBA). The user interface (UI) and the business logic was tightly coupled with the data but was logically and physically separated into two layers. Developers used programming languages such as Clipper, dBASEIII, and PowerBuilder to implement systems using two-tier architecture.

Three-Tier Architecture: The introduction of various distributed computing technologies for information exchange and data access led to the three-tier architecture by separating the user interfaces, business logic, and data into individual tiers. Information exchange technologies (such as OLE, COM, COM+, DCOM, ActiveX, CORBA, and RMI/IIOP) and data access technologies (like OLE-DB, ODBC, DAO, and JDBC) introduced the power and linking capabilities of a three-tier architecture. Three-tier architecture became popular during this time, and data centers had application servers and database servers while user interfaces ran in the desktop computers of the users. Also, three types of developers operated in this model as backend developers (who develop business logic) and frontend developers (who develop user interfaces) and database administrators (DBAs). To strengthen this pattern, a number of frameworks came into the market, such as Enterprise Java Beans (EJB) and Microsoft.Net.

Model View Controller (MVC): Web-based applications were enhanced in the dotcom era, and, as a result, a web-friendly MVC architecture pattern was introduced. The MVC approach held on to the three-tier architecture by changing the layer-to-layer data flow to a triangular flow. In principle, three-tier architecture does not recommend the UI layer directly accessing the data. The MVC pattern changed this by allowing the UI to interact with the data layer directly. This was further improved with the introduction of MVC-2.

N-Tier Architecture: Smart devices added another application type—mobile apps. As a result, three-tier architecture moved to n-tier, and this allowed architects to add many system layers based on application needs. For example, some systems introduced the client logic layer and made the web and mobile apps thin clients. Also, the n-tier approach moved data logic out of the core data storage and introduced a new data processing and manipulating layer. Data flow moved back to the layer-to-layer sequential flow.

Service-Oriented Architecture (SOA): Web services standardized distributed system calls by introducing interface definitions (contracts) and message formats, which were initially XML based. In addition, web services simplified remote procedure calls and brought in the concept of business interfaces and business data. As a result, a new architecture layer was added to the n-tier architecture: the services layer. As the entire architecture was created based on services, it was named service-oriented architecture. Later on, services were categorized as data services, business services, composite services, etc., and each service category represented an architecture layer. SOA was further improved with the addition of many sub-architecture patterns, such as event-driven architecture (EDA) and web-oriented architecture (WOA).

This paper mainly focuses on the layered and segmented architecture(s) defined after SOA.

Microservice Architecture (MSA): The theory behind microservices proposed a decentralized and non-layered architecture. However, most enterprises that adopted MSA ended in a layered architecture once they started reusing existing systems and data as well as the added quality of services.

One of the main motivations behind the Cell-Based Architecture (CBA) was to find the right reference architecture to enable MSA outside a layered approach. Cell-Based Architecture is an API-led decentralized reference architecture that is compliant with Microservice Architecture (MSA) and Cloud-Native Architecture (CNA).

The system of systems concept groups the functionality and the teams (people) associated with delivering the functionality. The system of record, system of operations, system of engagement, and system of intelligence are a few high-level classifications that derive into subsystems based on the size and the complexity of the overall system.

There were various usage patterns that were introduced from time to time-based on functionality enhancements. As an example, API management introduced an API gateway layer, identity and access management (IAM), and analytics moved to a centralized service layer. At the same time, infrastructure-related operations moved to an infrastructure as a service layer. These patterns influenced the shape of layered architecture.

For nearly two decades, reference architectures primarily focused on layers, where comparable functional capabilities were grouped into layers by following the SoS approach. Centralized data moved from one layer to another. Layered architecture not only created architecture and technology layers but it also created a culture, an organization structure, and a new way for how teams operate. There are pros and cons to using this pattern. We position this as part of the emerging architecture pattern by considering enterprises that are moving from brownfield to greenfield and heavy usage of this pattern on the systems already built and providing a digital experience for consumers.

Layered architecture is a natural progression based on how hardware and software systems have evolved, which started from tightly coupled, centralized, and single-purpose systems to distributed (centralized) multi-functional systems and modern decentralized any-functional systems.

The movement of hardware and software, in addition to the hierarchical and centralized setup of the organization structure, was also an excellent fit for layered architecture. In such an organization, sub-teams are disconnected and operate as silos. Centralized, layered architecture helps these disconnected teams to connect by making the centralized system the source of truth.

As noted at the beginning of this paper, in a layered architecture, components are the atomic units. Components that provide similar functional capabilities are grouped into layers. Layers are arranged as a stack.

The number of layers is not fixed. However, at least three layers introduced by the three-tier architecture (presentation, logic, and data) exist in most layered architecture approaches. The complexity of the systems and the level of distribution (separation of concerns), introduced sub-layers to the basic three layers.

Data flow in a sequential manner from one layer to another. As a result, two layers cannot bypass a layer in between. Different message exchange patterns (MEPs) can be used to exchange data between each layer. An architect can use one or a combination of different MEPs. For example, request-response and publish/subscribe (pub/sub) MEPs can be used to exchange data between layers.

Developers working on and responsible for a layer experience the same behavior from the two layers surrounding it.

The above diagram represents a common layered architecture used by architects that used SOA to implement systems. However, this is not an architecture diagram used at the beginning of SOA—rather it presents an architecture after the SOA concepts were well established in the industry. Initial SOA concepts were built using a triangular web services model and consisted of a service provider, service registry or discovery, and a service consumer.

Architects extended the triangular model by following one of the fundamental concepts of SOA "decoupling" and grouped the decoupled functional capabilities into layers. Organizations modeled their teams and reporting structures to fit into the layered architecture and each layer became an individual team or even a business unit.

In fall 2015, I was involved in defining the future state architecture for a leading European automobile company. The company’s chief architect visited our office in California, and we started the project by taking the standard SOA-based layered architecture defined in the previous section. After a full working day and many whiteboard diagrams, we realized that single-dimensional layers could not represent the full architecture landscape we wanted. We started day two by extending the layered architecture to one that was multi-dimensional by bringing in application lifecycle stages and quality of services into separate dimensions. This allowed us to group cross-cutting concerns into different blocks within the layers and address a broader scope of capabilities.

The system of systems concept influenced this architecture as the foundation. Also, concepts such as Gartner's pace layered architecture and the functionality richness expected by the enterprise architecture considered heavily while defining this pattern.

We used this pattern to build many systems in medium to large enterprises, and still, many architects refer to this as a logical pattern.

Let's go through each layer in detail.

Source System of Record (SSoR): This is the layer that physically stores data. Different types of data storage can represent this layer. In reality, enterprises use heterogeneous data storage added with the time based on the internally and externally built systems introduced. This storage can vary from SQL, NoSQL, file system, to cloud storage, or a combination of these.

System of Record (SoR): This layer is responsible for managing and maintaining data stored in the SSoR layer. Typically a core system application represents this layer by encapsulating the SSoR.

Data Virtualization: This layer allows access to the SoR or multiple SoRs by building business objects. Data manipulation tools and technologies, such as master data management (MDM) and extract, transform, load (ETL), reside in this layer. Object-relational mapping (ORM), data services introduced by SOA, data APIs, and new data lakes implemented using data caches can be new additions.

Service-Oriented Architecture (SOA): The SOA layer contains the business logic and processes that expose the business capabilities as services. Traditional web service standards or RESTful service standards use this layer to define the interfaces on accessing the services.

Application Programming Interfaces (APIs): Data and business functionalities are exposed in secure and standard ways via (managed) APIs. The application developer only sees the APIs as the way to perform create/read/update/delete (CRUD) operations and execute business processes. APIs encapsulate the complexity of the underlying systems and data and provide a pure abstraction.

System of Engagement: This is the layer that human interaction happens through various applications, such as web and mobile applications. As we identified before, applications are built by consuming (managed) APIs. There can be a system-to-system interaction, and device interaction through IoT (Internet of Things) can represent this layer, in addition to human-centric applications. Even robotics is a candidate to represent this layer.

As explained previously, the difference between this layered architecture compared to the standard layered diagrams is the multi-dimensional aspect of it. So let's look at the horizontal view of the same.

System of Automation: Infrastructure, infrastructure as a service (IaaS), and virtualization of hardware, such as the physical location of different runtimes, runs in this layer. Besides, a supportive process of application lifecycle management, such as continuous integration (CI), continuous deployment (CD), infrastructure as a code, and various DevOps automation, represents this layer. This layer runs across the vertical layers we looked in the previous sections.

Application lifecycle stages (develop/publish/consume and run): Tools and actions bound with development sandbox environments are represented in the development layer. Once the application advances from the development by successfully passing the relevant quality tests, it gets promoted to the publishing stage. Publishing can proceed to a relevant listing (store or registry) as well as to an application composite repository. In some cases, it can be just a branch or a tag in the source control system, which contains a separate build pipeline. Application usage outside development and testing can be found in the consume and run layer. The production-ready versions of applications are represented here. In addition to the applications, the dependent runtimes in each vertical layer are presented from bottom to top (data to screen).

Quality of Services (QoS): We identified three primary quality of services in this architecture, which can engage at the runtime separated from the core application and business logic. Securing, governing, and monitoring the applications and business logic are added as separate horizontal layers.

The layered architecture described above does not look interesting for current greenfield projects that follow concepts such as microservices and cloud-native. The reality is that a majority of enterprises cannot take a 100% greenfield approach; it is a mix of brownfield and greenfield. Therefore, a multi-dimensional layered architecture is still used as a reference architecture to build large distributed systems. The next section explains a way to enhance this approach to address greenfield architecture requirements.

The term microservices was coined by Dr. Peter Rogers in 2005; however, it was adopted as an architecture pattern that could be applied to build production-ready systems in 2011. Best practices and guidelines provided by technology evangelists like Martin Fowler and organizations that adopted the principles, such as Netflix and Uber, made it famous in the architecture community.

However, architects found it difficult to apply all the theories associated with microservice architecture during that period. Development teams started writing microservices when they revamped existing services or when introducing new services. At the same time, greenfield projects started adopting microservices. But those microservices had to fit into the overall application architecture due to various reasons, such as fetching data, integrating with business processes, and even producing data to various end-user applications residing in the system of the engagement layer. As a result, microservices became another layer in layered architecture. The following diagram explains how microservices fit into the layered architecture during the early stage.

Primarily the business logic and integration logic focused on service composition (orchestration and choreography) moved to microservices. The centralized nature of the runtime, dependency with multiple application architecture layers, and hypervisor-based and bare-metal infrastructure did not support the flexibility and depth required for MSA. Container-based infrastructures were there at that time, such as Linux Containers (LXC) and Warden, but they were not mature enough to run production systems.

To break the limitations identified above, application and DevOps architects came up with a workaround. This is the birth of segmented architecture.

Organizations started moving to a podular architecture with small agile teams adapting to agile methodologies. Different terms were used to define these teams. Pods, two-pizza teams, and scrum teams are a few examples of this, and we call them self-organized teams. From a technical perspective, microservice architecture, virtualization, and containers helped these autonomous teams to operate successfully. Some teams started bypassing corporate IT and moved to their hosting options, such as public clouds. We call it 'Shadow IT.' To avoid Shadow IT, responsive IT concepts were introduced by corporate IT teams, and segmented architecture is a result of that.

The fundamental concept behind layered architecture did not change in segmented architecture. However, segmented architecture introduced more freedom for application development teams than layered architecture by creating isolation and ownership of runtimes by partitioning using segments.

Segments were created based on how each enterprise was organized; in some cases, it was based on the business units, a set of functionality delivered to larger application systems, or center of excellence (CoE) teams. The team owns the segment and has access to the segment in different environments associated with the lifecycle of the application, such as development, testing, staging, and production.

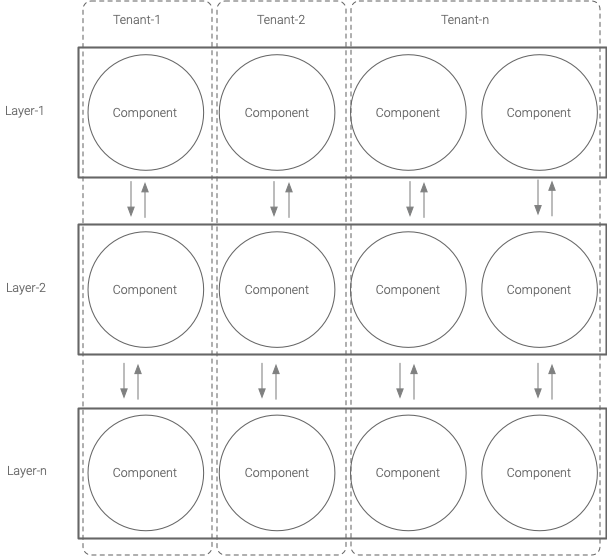

The above diagram illustrates a logical abstraction of segmented architecture. Architecture layers remain as it is, and the data flow happens from one layer to another. However, the components in each layer are grouped as segments. Segmentation is implemented using the combination of infrastructure capabilities and security, such as role-based access control (RBAC) and entitlement policies. Organizations are taking different approaches to achieve segmentation. They can be categorized into three areas.

- Runtime partitioning

- Multi-tenancy

- Platform of platforms

In the runtime partitioning approach, components inside a layer are grouped as segments, which adheres to the fundamentals of the segmented architecture pattern. The partitioning of components (or runtimes) is done based on the development and production deployment needs and isolation requirements. The following diagram shows a segmentation approach based on the business domains. Only the services layer is segmented based on the business domains and each segment is owned by an individual team. The remaining layers (other than domain services) are not partitioned and act as shared services across segments.

Multi-tenancy introduced a way to provide isolation in hosted solutions, such as software as a service (SaaS) or platform as a service (Paas). Later on, the same concept was utilized to achieve segmentation in application development. Layered architecture platforms started providing the runtime capabilities and used a tenant as the boundary for each team. The common practice is to provide a tenant in each layer, but it can be obsolete in some layers and make them shared across the tenants. The system of record layer is an example of a shared layer.

Types of Multi-tenancy in Message-oriented Middleware

- Shared data, control, and management plane

- Individual data plane, shared control and management plane

- Individual data and control plane, shared management plane

Based on various functional and non-functional requirements, internal and external service providers decide which model of multi-tenancy should be offered to consumers. Isolation requirements of functional runtimes, security, and system load are some considerations service providers have to take into account when making this decision.

If you are new to the concept of the data, control, and management plane, please refer to this article.

In this approach, the entire platform is duplicated and is treated as a segment for a business unit or an agile team. When a new project or a business unit requires an environment, the authorized infrastructure team provision and spin up the entire platform and hand it over to the required team. The platform of platforms is a costly approach from an infrastructure point of view. Each team might require several environments based on their application development lifecycle. The number of environments can vary by the size of the team and the nature of the applications they build. For example, Team A requires development, testing, and production environments, while Team B needs development, testing, staging, production-blue, and production-green environments. In this approach, a clone of the same platform is required to represent each environment. However, there are considerable advantages in terms of productivity; the isolation of runtime environments allow teams to independently develop and release the products or the services they own. Most organizations offer some services across the platforms, such as master data, identities, user stores, and build processes associated with the CI/CD pipeline.

In this section, we look at the relationships between APIs and layered and segmented architecture patterns.

In the prior section, we looked at the architecture evolution that occurred during the past two decades. The above table is a snapshot of how APIs evolved during the same period. If you carefully analyze both, there is a synergy we can see in both progression paths that involve APIs from the beginning. Therefore, APIs were involved in each architecture approach in different forms and characteristics. Digital transformation, consumer-driven application requirements, and business-focused application development led APIs to shift to the right—from technical APIs to business-friendly APIs.

The components in an application architecture expose the functional capabilities as APIs. These APIs are created using different message exchange patterns, transports, and formats. The purpose of the APIs varies based on the nature of the component. Based on various usage patterns, we have categorized APIs into three buckets.

Applications (or things) consuming the APIs require the message exchange between the API gateway and the application based on usage. For example, a mobile application on the move requires an asynchronous message exchange to the service during connection interruptions. Therefore, the APIs have to support multiple message exchange patterns. There are three main API types identified based on the behavior. Most of the API gateways available in the market support these three types.

Different behavioral APIs can be exposed using a single API gateway or use separate gateways per each behavioral type. The decision might depend on the functional capabilities of the API gateway and the architecture.

The reason for claiming layered architecture as an API-centric approach is highlighted in the following diagram. APIs act as the glue to connect the layers. Based on the functional capabilities exposed, the API type varies and fit into a category explained in the previous section.

While bridging connectivity between layers, APIs connect components within the layers as well. Connectivity between the components shares either business- or system-level information based on the runtime need.

Inherited from the generic layered architecture connection with APIs, SOA uses the same concept.

A new layer called API management was added to the architecture and resides between end-user applications and services. Utility APIs and domain APIs mainly are consumed internally; hence, additional control and security are required for the edge APIs that service end-user applications.

The nature of the systems residing in each layer mandate the type of APIs exposed. Behavioral API models come in handy here to support that. In addition, heterogeneous systems expect various message formats and security standards, so message mediation and security bridging are common practices in this architecture pattern. Traditional enterprise service bus (ESB), composite services, and API gateways facilitate the mediation processes. Mediation is an overhead due to the added latency, but it can instantly negotiate by looking at the simplicity brought to the architecture and functional capabilities.

The usage of APIs in the segmented architecture is similar to the layered architecture. However, it increases dependency because a business unit or a team owns each segment. The only way (or recommended way) is to use APIs to communicate between the segments. Similar to the layered architecture, APIs will glue the segments as well as components inside each segment. In general, edge APIs get exposed between segments, but there are no restrictions to prove the capabilities as domain and utility APIs.

The usage and deployment of API gateways depend on the segmentation technique used. Shared gateways can be applied to runtime partitioning and multi-tenancy patterns, while independent gateways can be used in all three models, including platform of platforms.

The two architecture patterns discussed in this paper (layered and segmented) originate from the same family, i.e., centralized. The sequential data flow from one layer to another is a common characteristic in both designs. Segmented architecture provides more flexibility for agile teams than layered architecture because of the elongated isolation provided by the segments.

The evolution of architecture and APIs happened in parallel. The type of APIs, protocols, and technology used to build the APIs varied based on the improvements in distributed computing, API economy, and organization structure. APIs act as the glue between the layers and components inside the layers.

Architects have the freedom to pick the right reference architecture based on the application and organizational needs. If you are looking for a decentralized approach, you can refer to the Cell-based Architecture (CBA). The Methodology for Agility defines a guide to implement these three architecture patterns.

Note from the author: I have been involved in implementing more than 1000 projects using layered and segmented architecture in many parts of the world. Even the current trend of decentralized architecture, layered architecture, and segmented architecture is a valid architecture that can be beneficial for many organizations. If you are looking for guidance for picking the correct architecture for your project, I'm happy to guide you using a strategic consultancy engagement.