So far, we’ve been doing single-key transactions, or transactions where only a single private key per input has to sign in order to disperse the funds. But what if we wanted something a little more complicated? A company that has $100 million in Bitcoin might not want funds locked to a single private key as that key can be stolen by an employee. Loss of a single key would mean all funds would then be lost. What can we do?

The solution is multisig, or multiple signatures. This was built into Bitcoin from the beginning, but was clunky at first and so wasn’t used. In fact, as we’ll discover, it turns out Satoshi never really tested OP_CHECKMULTISIG as it has a very obvious off-by-one error (see OP_CHECKMULTISIG Off-by-one Bug later in the chapter). The bug has had to stay in the protocol as fixing it would require a hard fork. In addition, it’s possible that certain multisig transactions that haven’t been broadcast yet would be invalidated, which could cause inadvertant loss of funds.

|

Note

|

Multiple Private Keys to a Single Aggregated Public Key

It is possible to "split" a key into multiple private keys and use an interactive method to aggregate signatures, but this is not a common practice. Schnorr signatures will make aggregating signatures easier and perhaps more common in the future. |

Bare Multisig was the first attempt at creating transaction outputs that require signatures from multiple parties. To understand Bare Multisig, one must first understand the OP_CHECKMULTISIG operator. As discussed in Chapter 6, Script has a lot of different opcodes. OP_CHECKMULTISIG is one of them at 0xae. The operator consumes a lot of elements from the stack and returns whether or not the required number of signatures are valid for a transaction input.

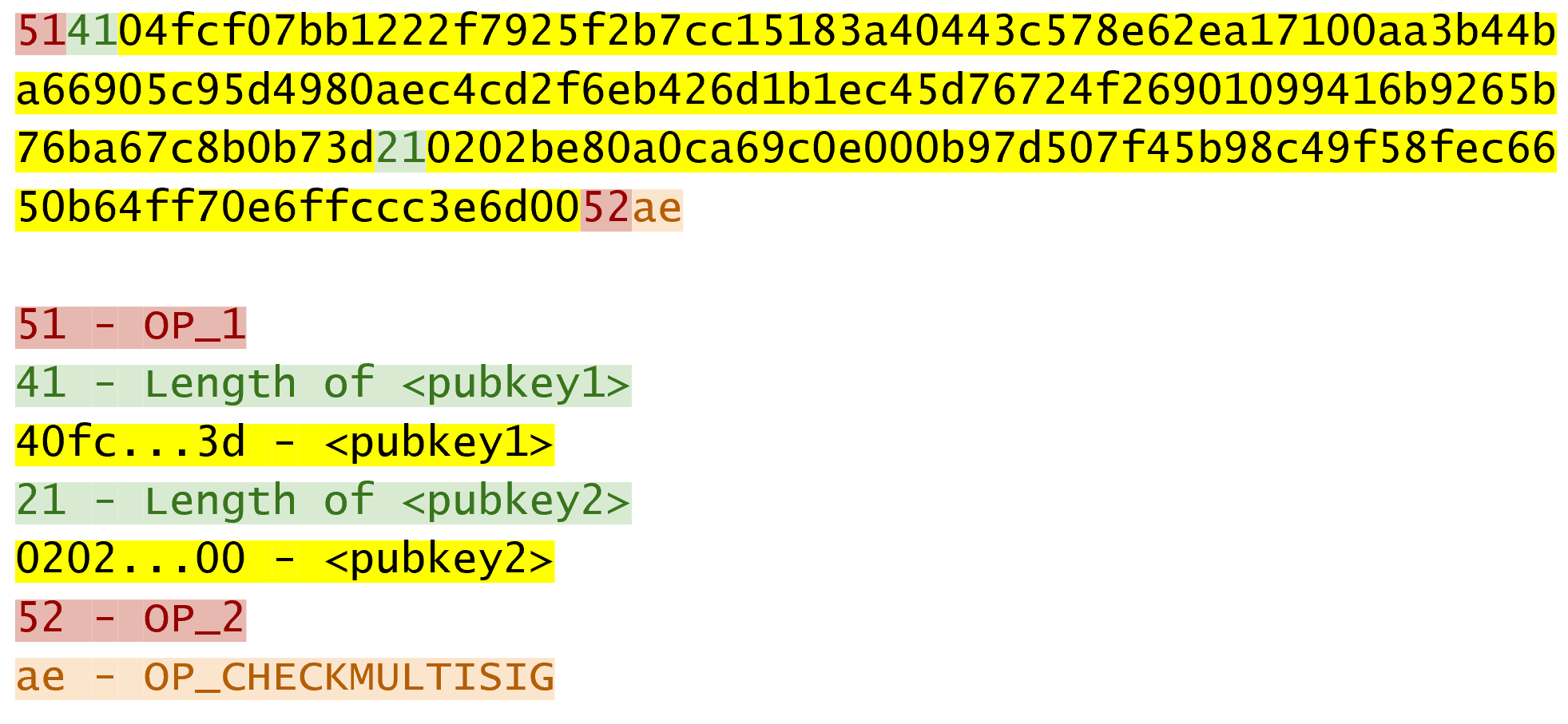

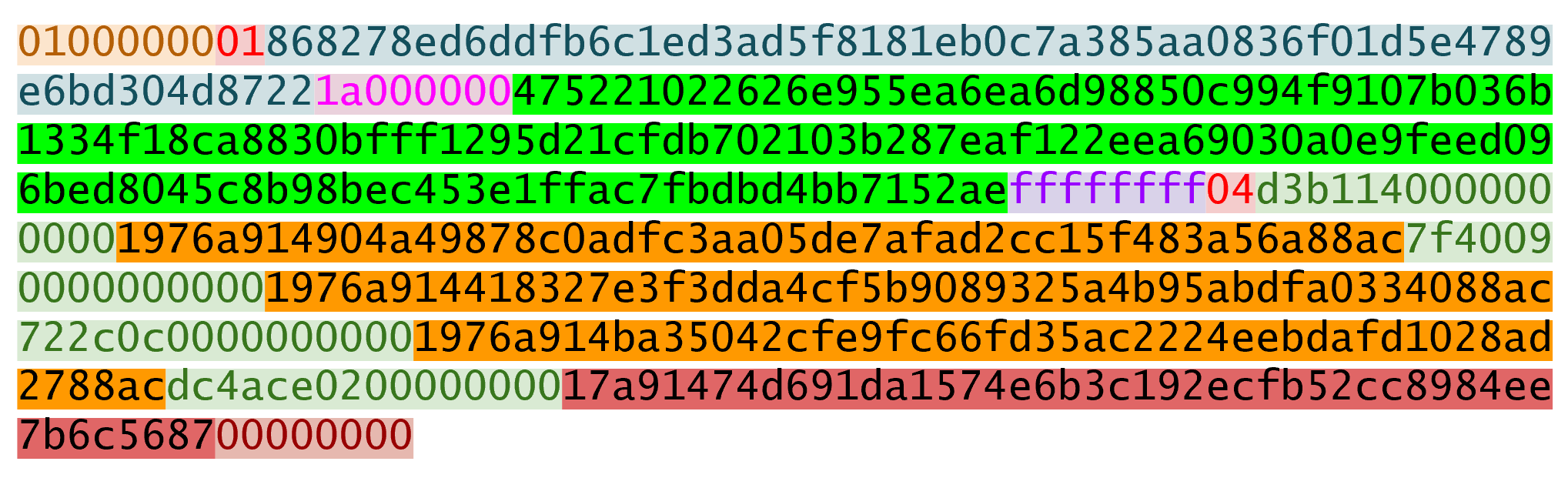

The transaction output is called "bare" multisig because it’s a really long ScriptPubKey. Here’s what a ScriptPubKey for a 1-of-2 multisig looks like.

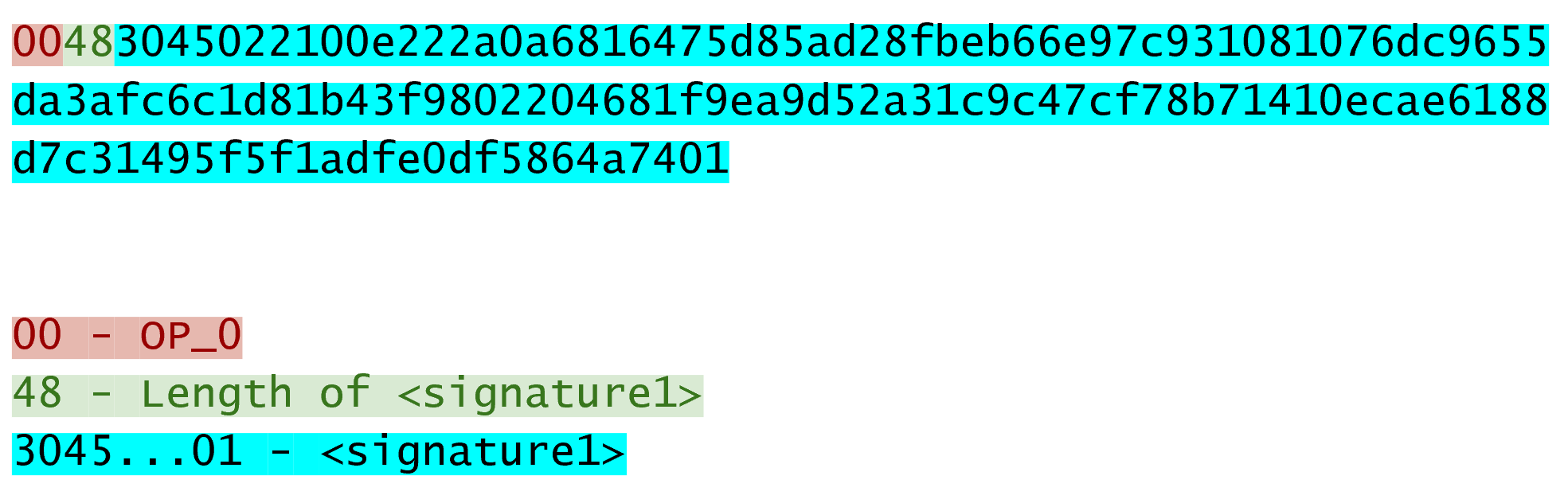

This is a reasonably small multisig, and it’s already really long. Note that p2pkh is only 25 bytes whereas this one is 101 bytes (though obviously, compressed SEC format would reduce it some), and this is a 1 of 2! Here’s what the ScriptSig looks like:

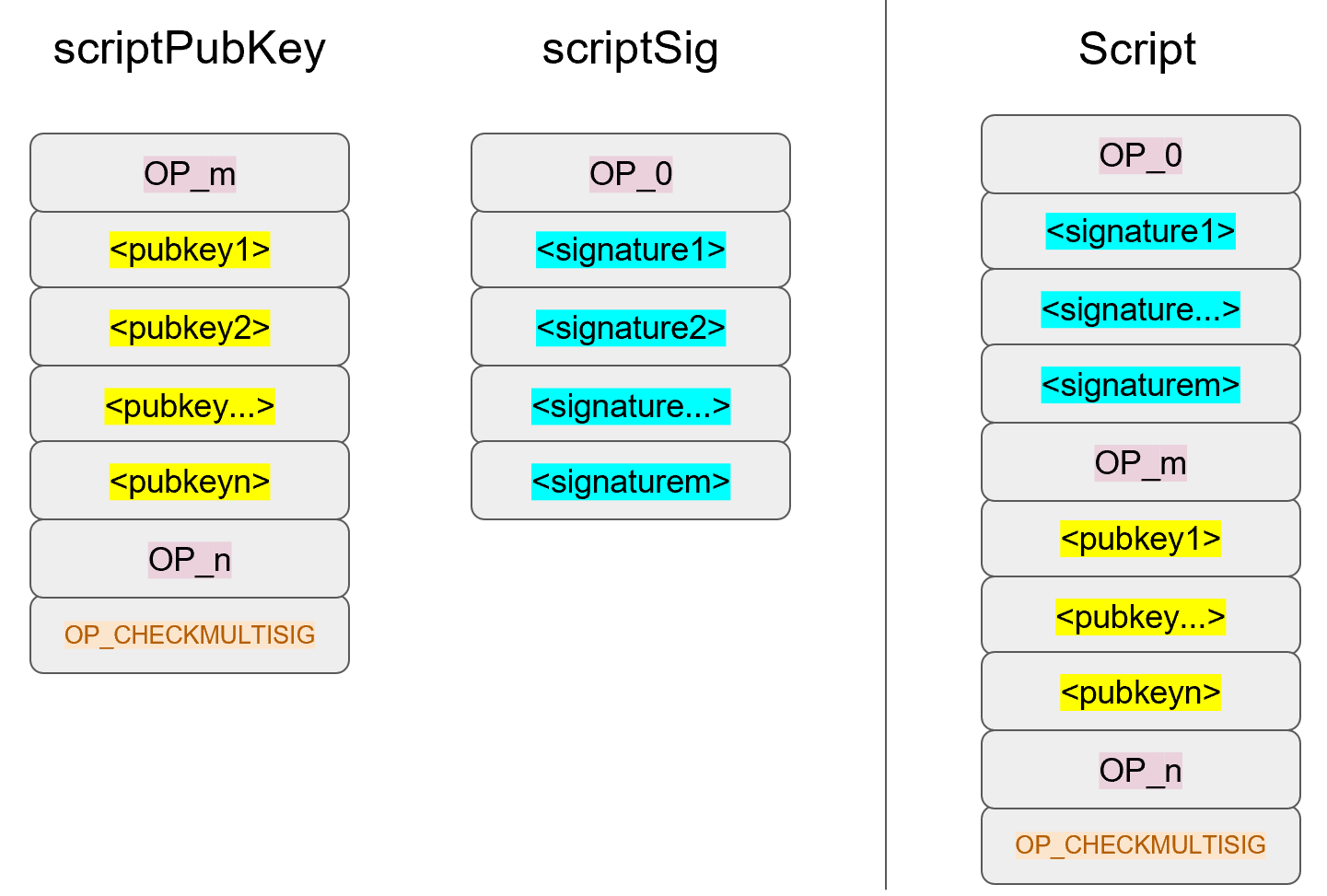

We only need 1 signature for this 1-of-2 multisig, so this is relatively short, though something like a 5-of-7 would require 5 DER signatures and would be a lot longer (360 bytes or so). Here’s how the two would combine

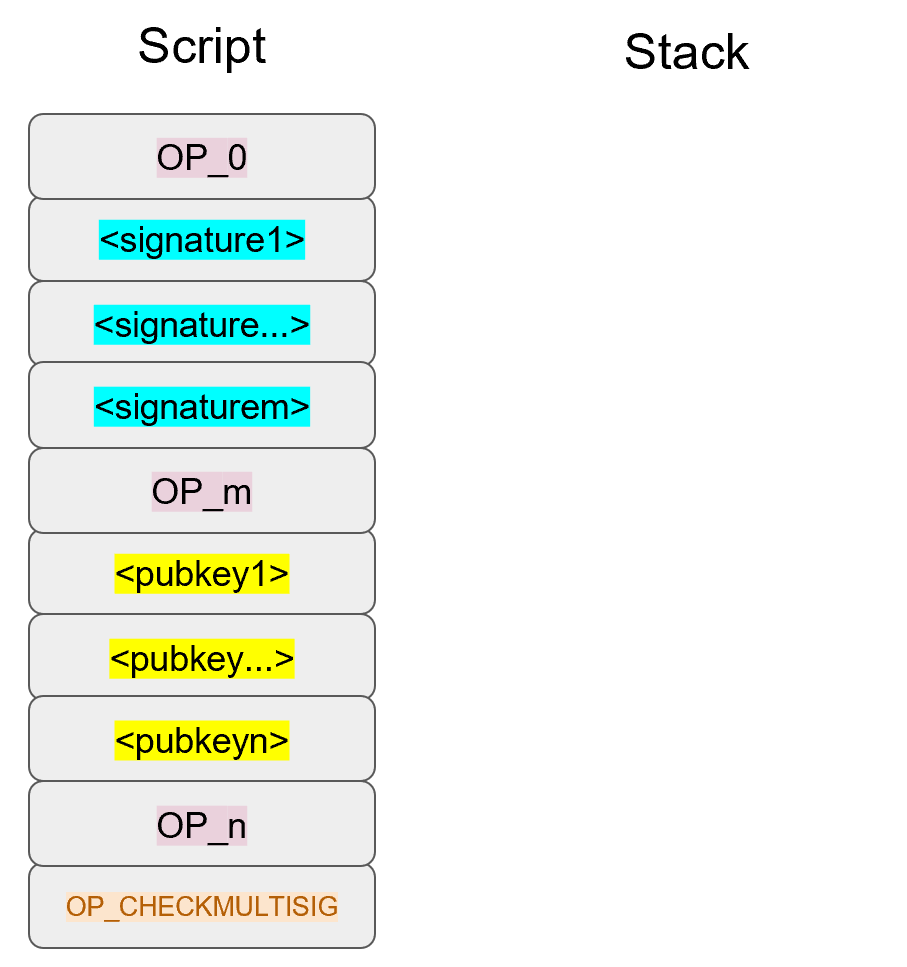

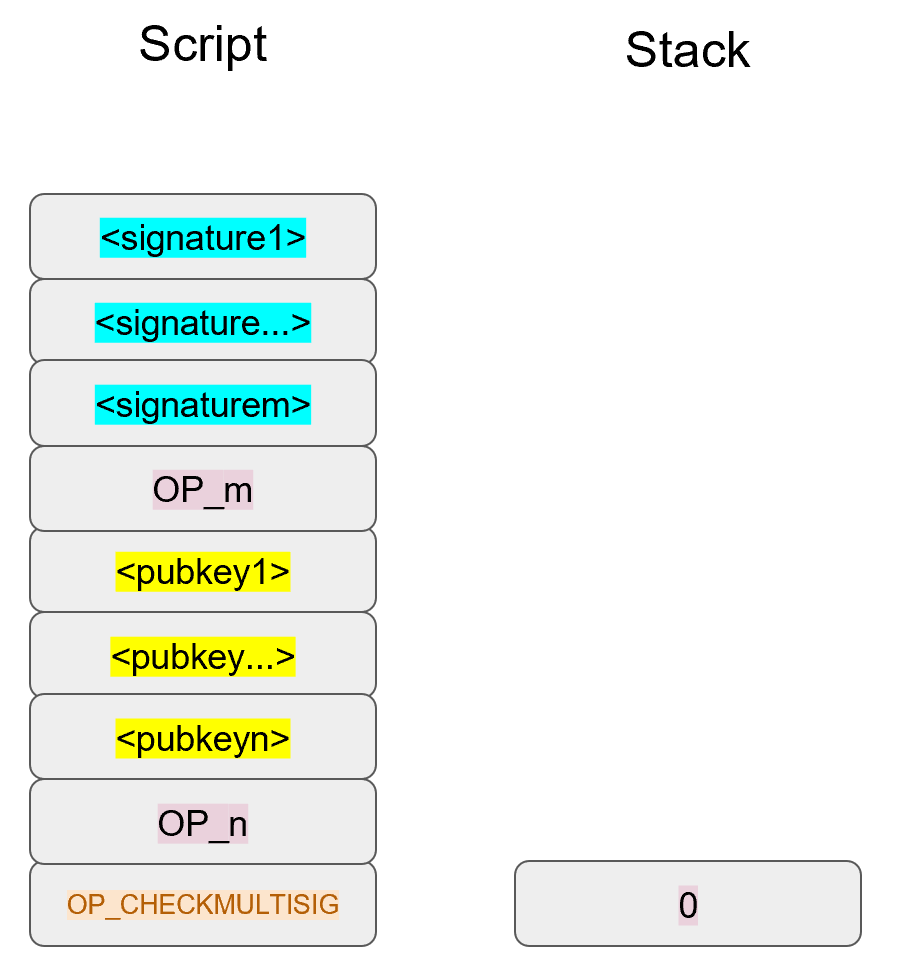

We’ve generalized here so we can see what a m-of-n multisig would look like (m and n can be anything from 1 to 20, though there’s numerical opcodes only go up to OP_16, 17 to 20 would require something like 0112 to push the number 18 to the stack). Note the OP_0 at the top. The Script stack starts like this:

OP_0 will push a 0 on the stack.

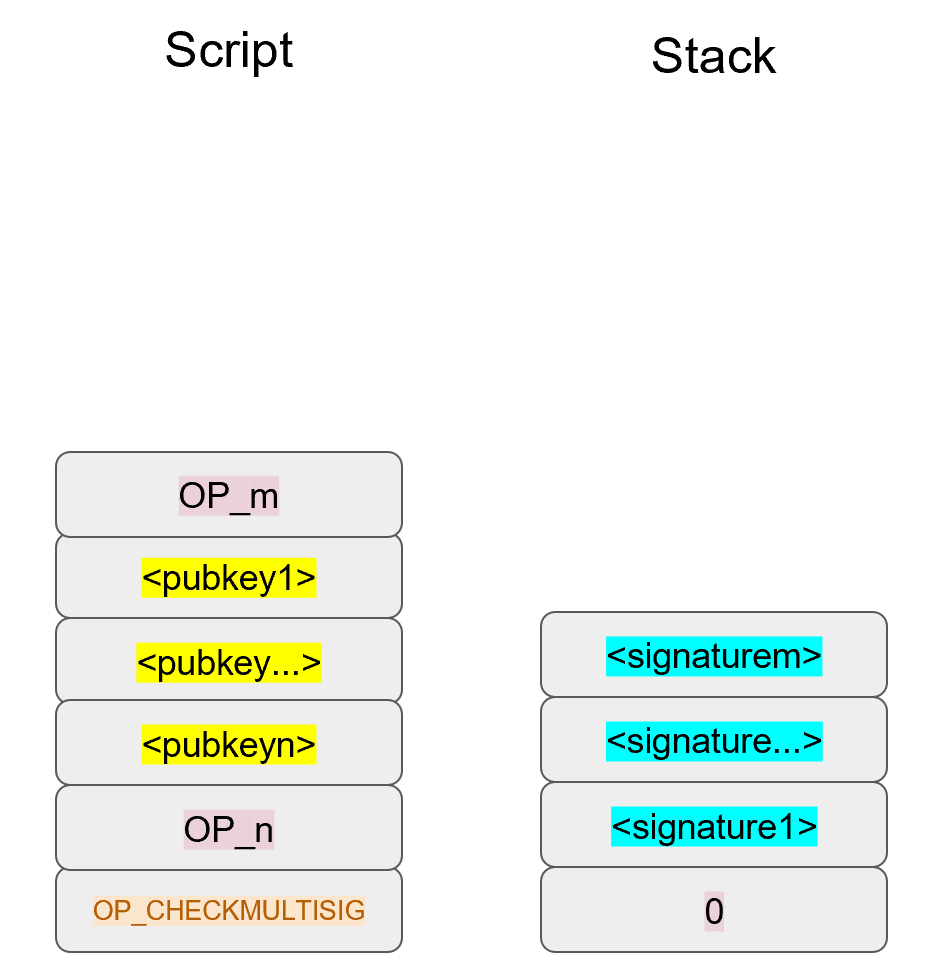

The signatures are elements so they’ll be pushed straight on the stack.

OP_m will push the number m on the stack, the public keys will be pushed straight on the stack and OP_n will push the number n on the stack.

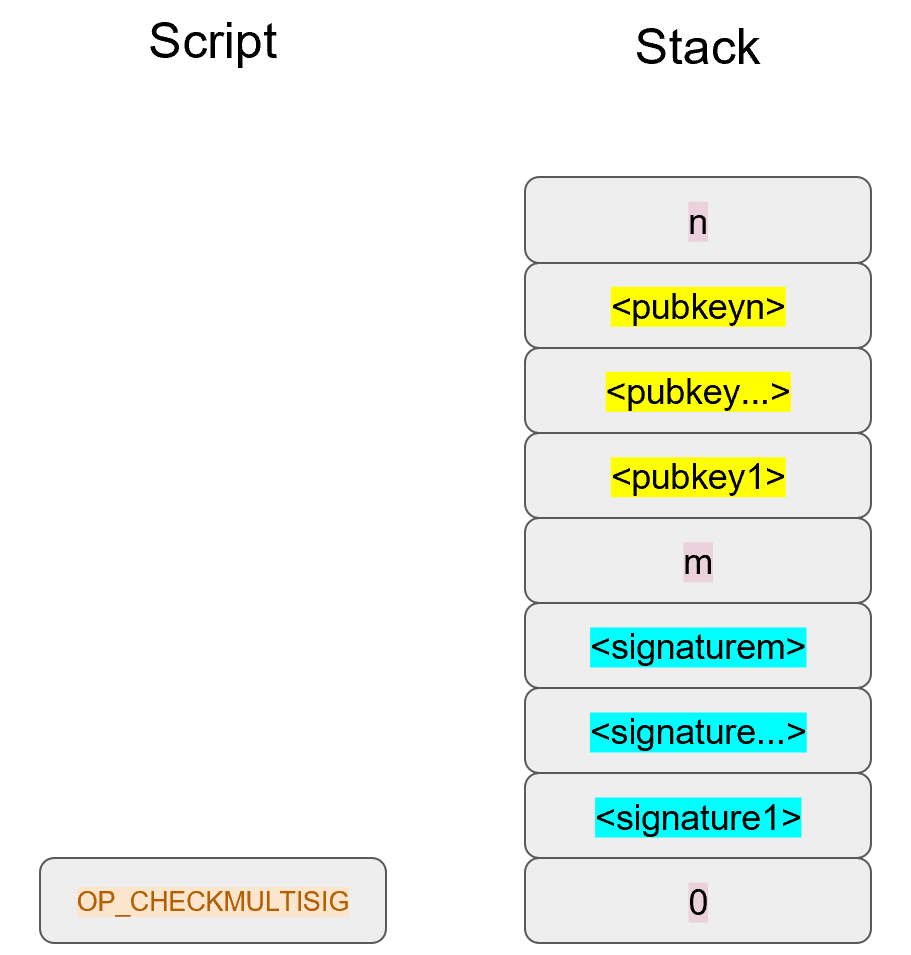

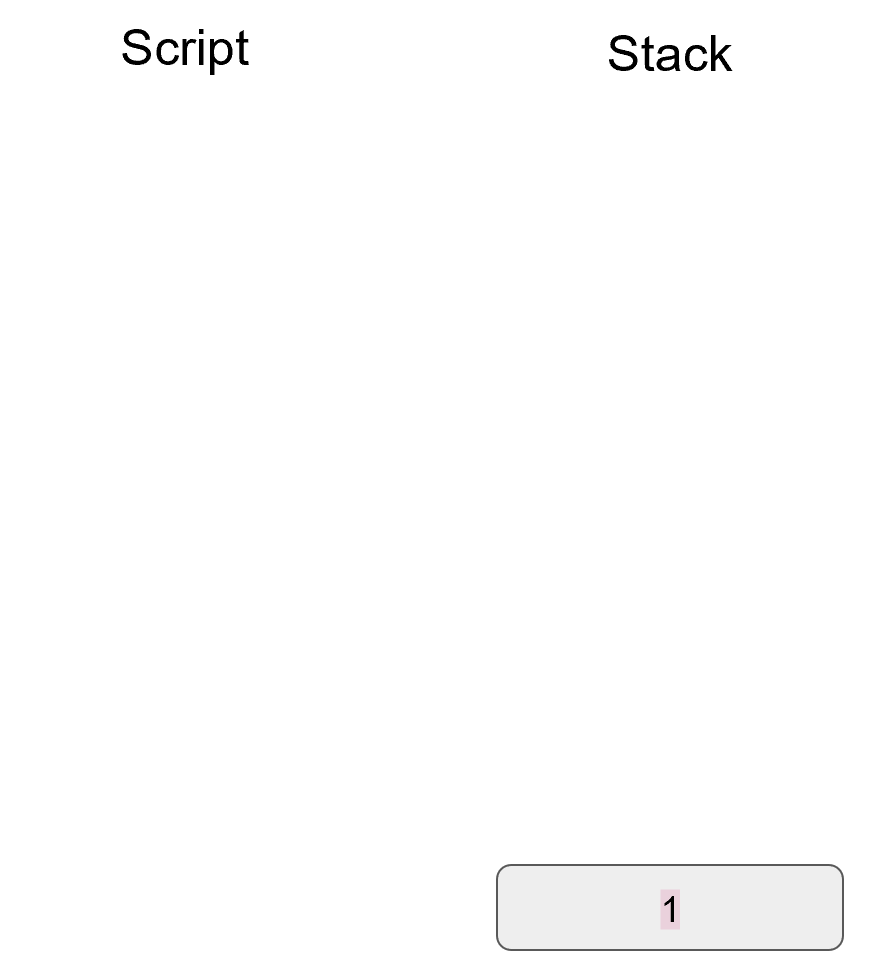

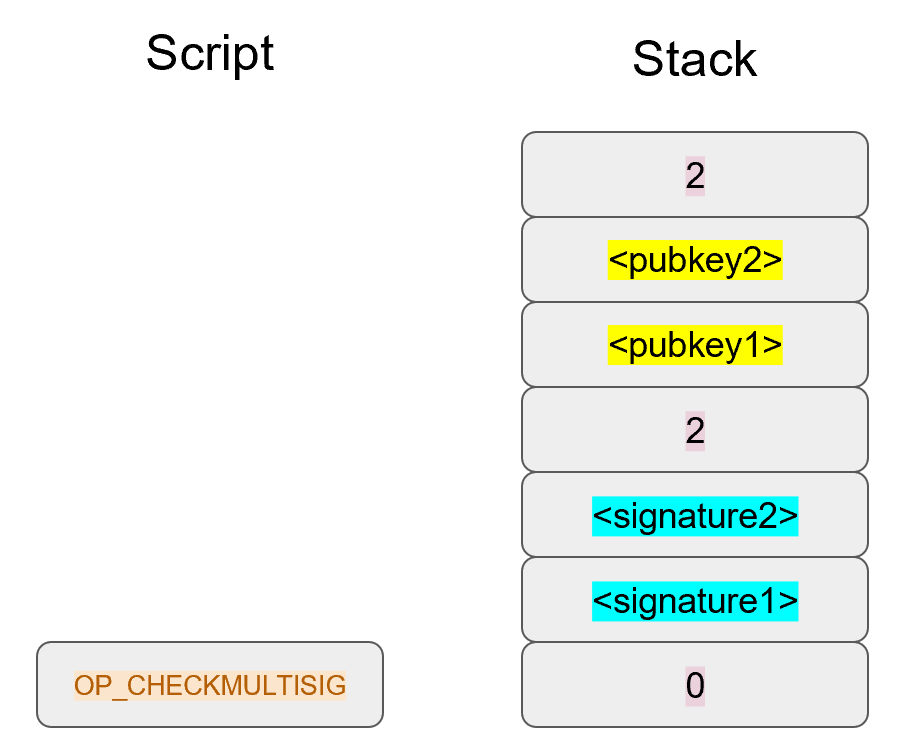

At this point, OP_CHECKMULTISIG will consume m+n+3 elements (due to off-by-one bug, see OP_CHECKMULTISIG Off-by-one Bug) and return 1 if m of the signatures are valid for m distinct public keys from the list of n public keys. Assuming that the signatures are valid, we are left with a single true item on the stack:

OP_CHECKMULTISIG Off-by-one BugThe elements consumed by OP_CHECKMULTISIG are supposed to be:

m, m different signatures, n, n different pubkeys.

The number of elements consumed should be 2 (m and n themselves) + m (signatures) + n (pubkeys). Unfortunately, the opcode actually consumes 1 more element than the m+n+2 that it’s supposed to. OP_CHECKMULTISIG consumes m+n+3, so the extra element is added in order to not cause a failure. The opcode does nothing with that extra element and that extra element can be anything.

As a way to combat malleabilty, however, most nodes on the Bitcoin network will not relay the transaction unless that extra element is OP_0. Note that if we had m+n+2 elements, that OP_CHECKMULTISIG will just fail as there are not enough elements to be consumed and the transaction will be invalid.

In an m-of-n signature multisig, the stack contains n as the top element, then n pubkeys, then m, then m signatures and finally, a filler item due to the off-by-one bug. The actual code for OP_CHECKMULTISIG in op.py is mostly created for you:

def op_checkmultisig(stack, z):

if len(stack) < 1:

return False

n = decode_num(stack.pop())

if len(stack) < n + 1:

return False

sec_pubkeys = []

for _ in range(n):

sec_pubkeys.append(stack.pop())

m = decode_num(stack.pop())

if len(stack) < m + 1:

return False

der_signatures = []

for _ in range(m):

der_signatures.append(stack.pop()[:-1]) # (1)

stack.pop() # (2)

try:

raise NotImplementedError # (3)

except (ValueError, SyntaxError):

return False

return True-

Each DER signature is assumed to be using SIGHASH_ALL. This isn’t required, but is generally the case on the network as of this writing.

-

We have to take care of the off-by-one error by popping off the stack and not doing anything with the element.

-

This is the part that you will need to code for the next exercise.

Bare multisig is a bit ugly, but it’s very much functional. You can have m of n signatures required to unlock a UTXO and there is plenty of utility in making outputs multisig, especially if you’re a business. However, bare multisig suffers from a few problems:

-

First problem: the long length of the ScriptPubKey. A hypothetical bare multisig address has to encompass many different public keys and that makes the ScriptPubKey extremely long. Unlike p2pkh or even p2pk, these are not easily communicated using voice or even text message.

-

Second problem: because the output is so long, it’s rather taxing on node software. Nodes have to keep track of the UTXO set, so keeping a particularly big ScriptPubKey ready is onerous. A large output is more expensive to keep in fast-access storage (like RAM), being 5-20x larger than a normal p2pkh output.

-

Third problem: because the ScriptPubKey can be so much bigger, bare multisig can and has been abused. The entire pdf of the Satoshi’s original whitepaper is actually encoded in this transaction in block 230009:

54e48e5f5c656b26c3bca14a8c95aa583d07ebe84dde3b7dd4a78f4e4186e713. The creator of this transaction actually split up the whitepaper pdf into 64 byte chunks which were then made into invalid uncompressed public keys. These are not valid points and the actual whitepaper was encoded into 947 outputs as 1 of 3 bare multisig outputs. The outputs are not spendable but have to be kept around by full nodes as they are unspent. This is a tax every full node has to pay and is in that sense very abusive.

In order to combat these problems, pay-to-script-hash (p2sh) was born.

Pay-to-script-hash (p2sh) is a general solution to the long address/ScriptPubKey problem. It’s possible to create a more complicated ScriptPubKey than bare multisig and there’s no real way to use those as addresses either. To make more complicated Scripts work, we have to be able to take the hash of a bunch of Script instructions and then somehow reveal the pre-image Script instructions later. This is at the heart of the design around pay-to-script-hash.

Pay-to-script-hash was introduced in 2011 to a lot of controversy. There were multiple proposals, but as we’ll see, p2sh is kludgy, but works.

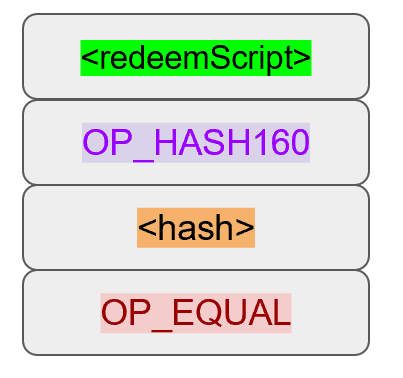

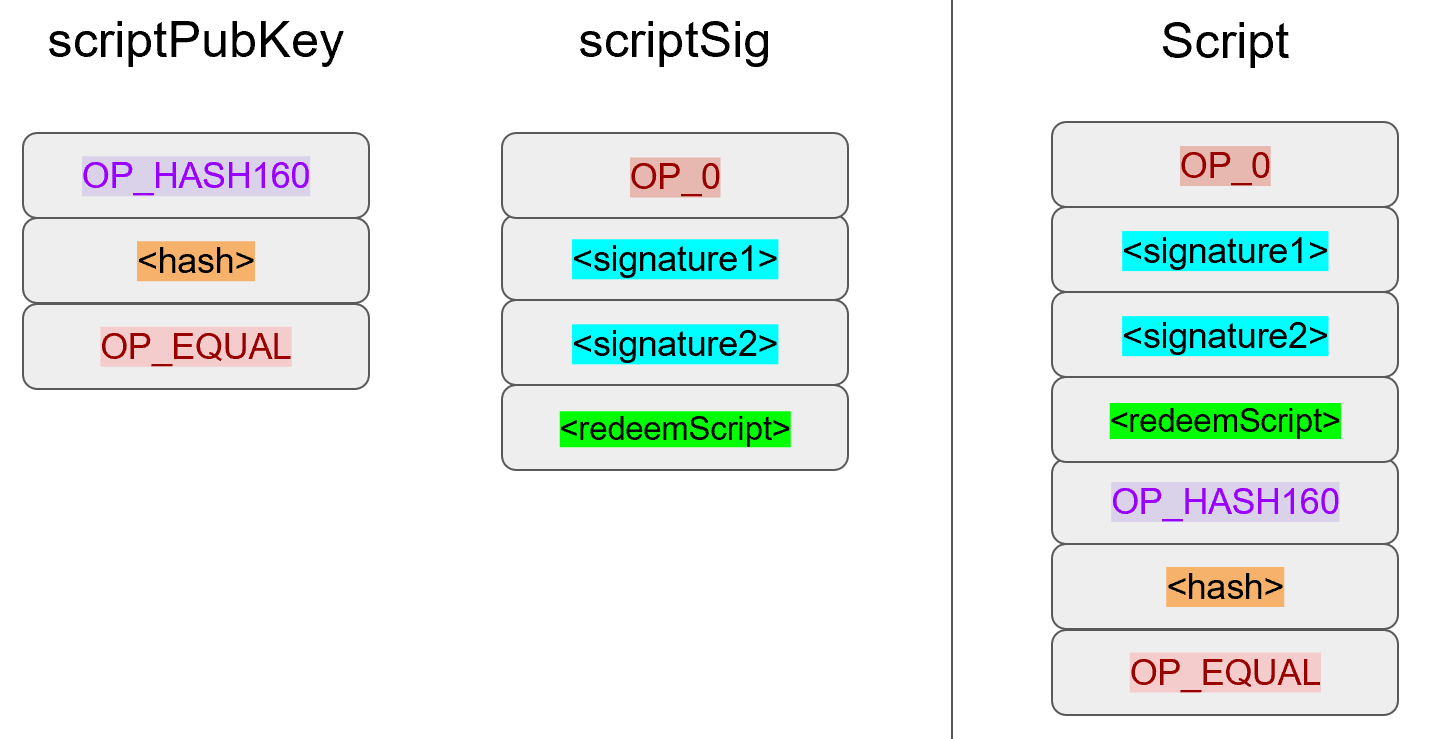

Essentially, p2sh executes a very special rule only when the script goes in this pattern:

If this exact sequence ends up with a 1, then the RedeemScript (top item in figure 8-9) is interpreted as Script and then added to the Script instruction set as if it’s part of the Script. This is a very special pattern and the Bitcoin codebase makes sure to check for this particular sequence. The RedeemScript does not add new Script instructions for processing unless this exact sequence is encountered.

If this sounds hacky, it is. But before we get to that, let’s look a little closer at exactly how this plays out.

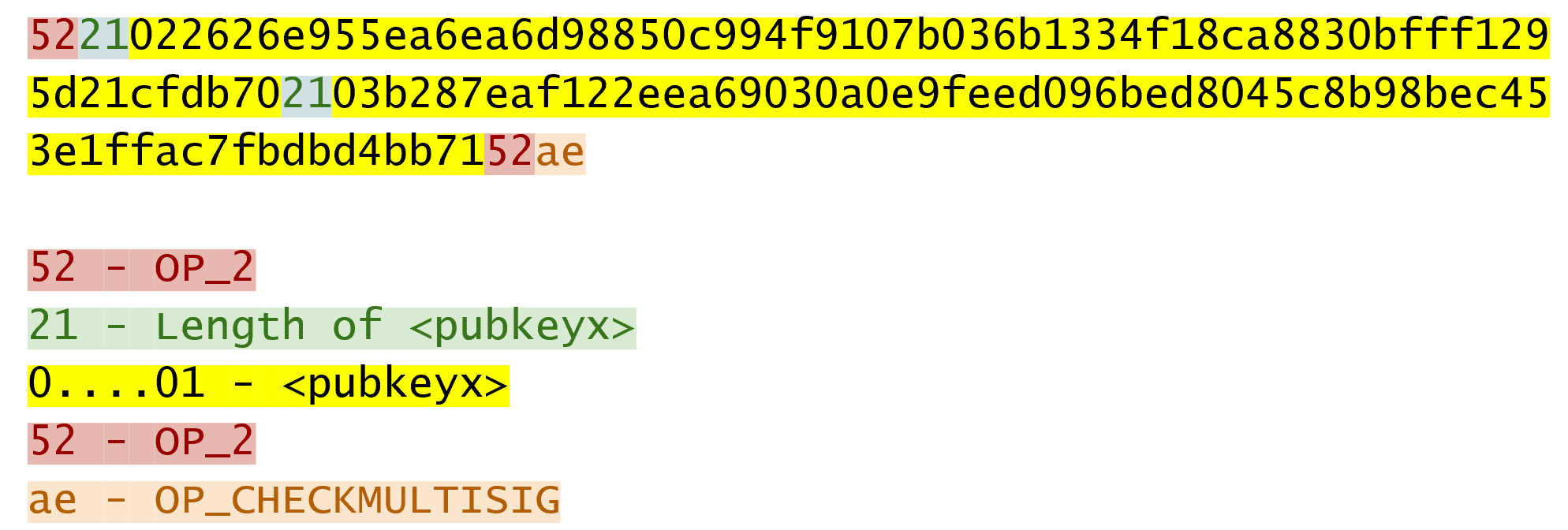

Let’s take a simple 1-of-2 multisig ScriptPubKey like this:

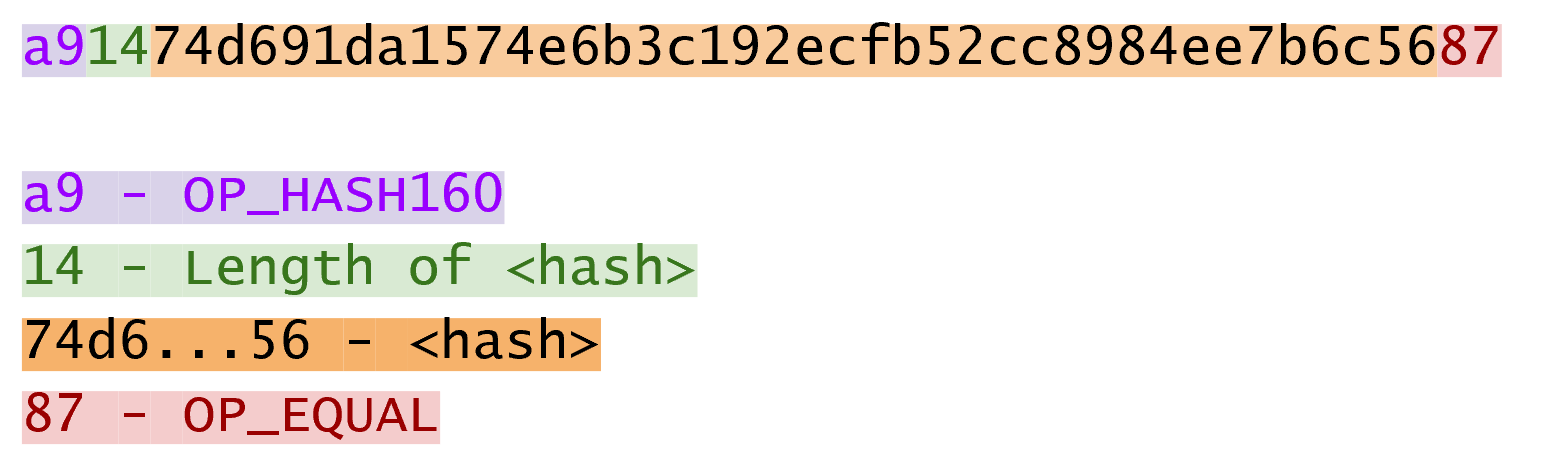

This is a ScriptPubKey for a Bare Multisig. What we need to do to convert this to p2sh is to take a hash of this Script and keep this Script handy for when we want to redeem it. We call this the RedeemScript, because the Script is only revealed during redemption. We put the hash of the RedeemScript as the ScriptPubKey like so:

The hash digest here is the hash160 of the RedeemScript, or what was previously the ScriptPubKey. We’ve essentially locked the funds to the hash160 of the RedeemScript and require the revealing of the RedeemScript at unlock time.

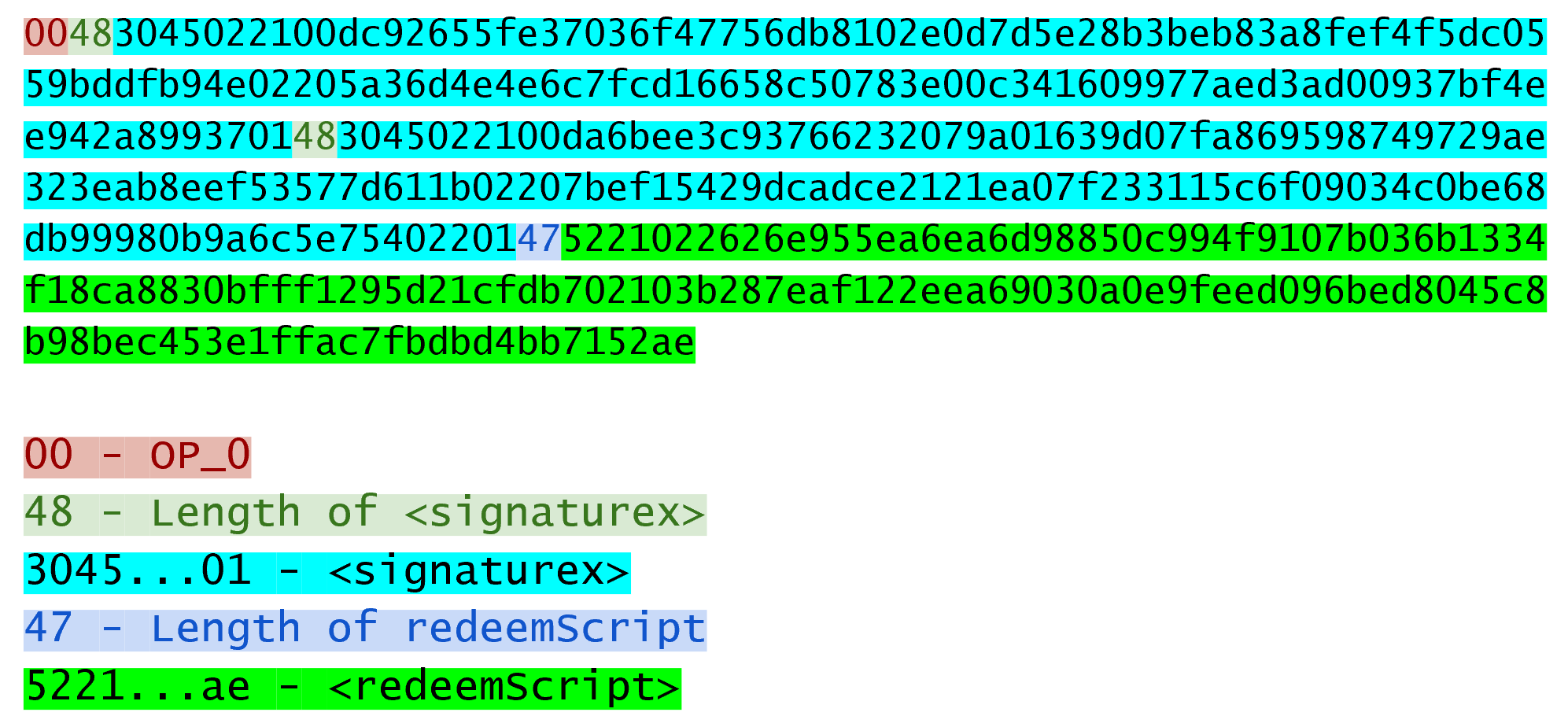

Creating the ScriptSig for a p2sh script involves not only revealing the RedeemScript, but also unlocking the RedeemScript. At this point, you might wonder, where is the RedeemScript stored? The RedeemScript is not on the blockchain until actual redemption, so it must be stored by the creator of the p2sh address. If the RedeemScript is lost and cannot be reconstructed, the funds are lost, so it’s very important to keep track of it!

|

Warning

|

Importance of keeping the RedeemScript

If you are receiving to a p2sh address, be sure to store and backup the RedeemScript! Better yet, make it easy to reconstruct! |

The ScriptSig for the 1-of-2 multisig looks like this:

This produces the Script:

Note that the OP_0 needs to be there because of the OP_CHECKMULTISIG bug. The key to understanding p2sh is the execution of the exact sequence:

Upon execution of this sequence, if the result is 1, the RedeemScript is inserted into the Script instruction set. In other words, if we reveal a RedeemScript whose hash160 is the same hash160 in the ScriptPubKey, that RedeemScript acts like the ScriptPubKey instead. We are essentially hashing the Script that locks the funds and putting that into the blockchain instead of the Script itself.

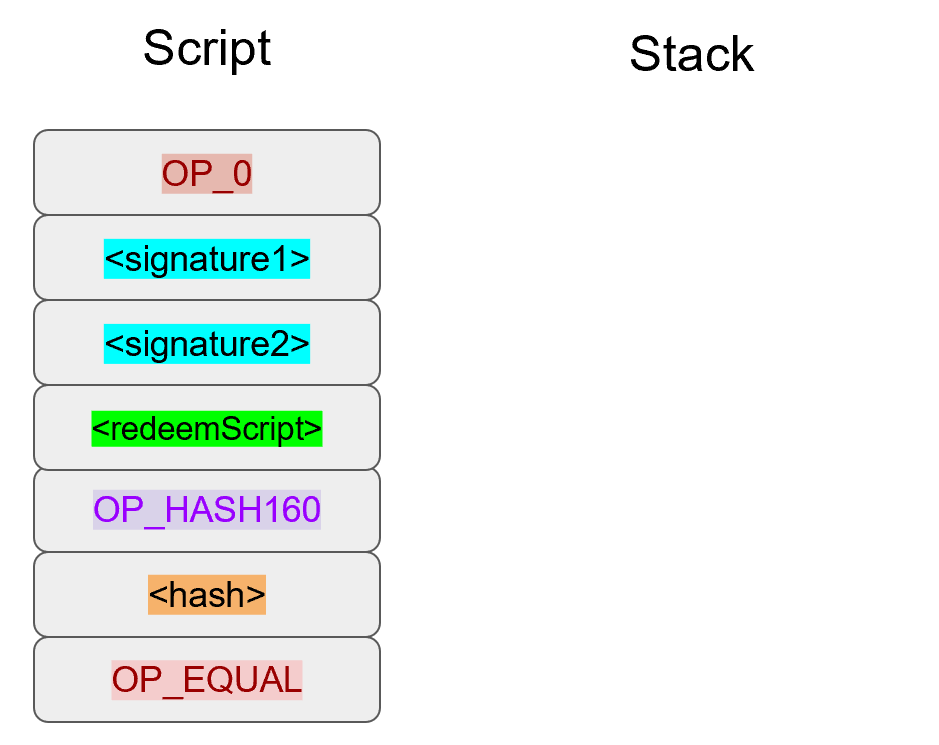

Let’s go through exactly how this works. We’ll start with the Script instructions:

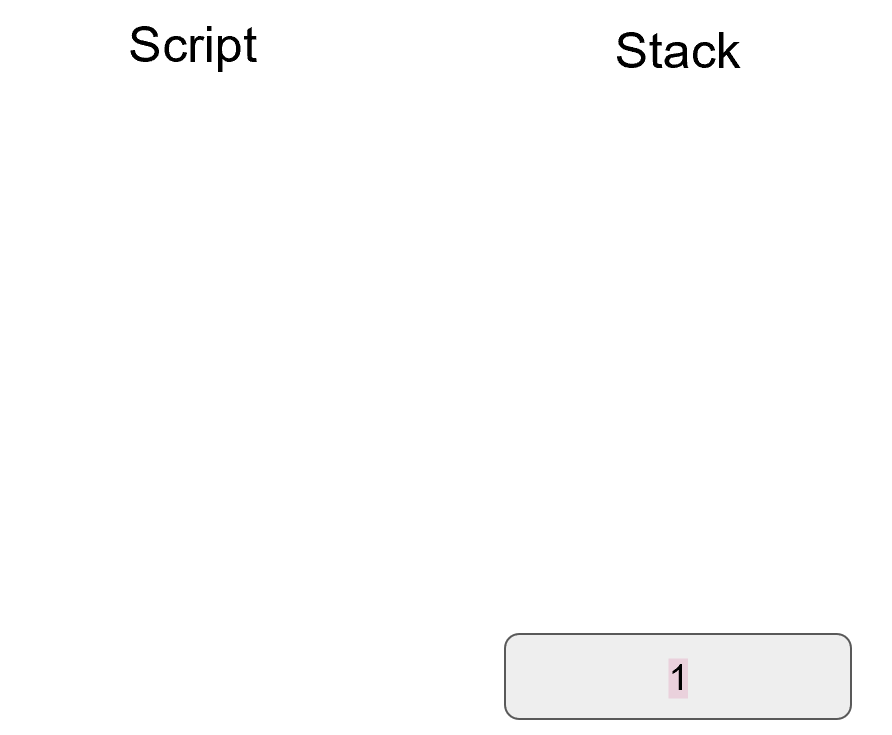

OP_0 will push a 0 on the stack, the two signatures and the RedeemScript will be pushed on the stack as elements, leading to this:

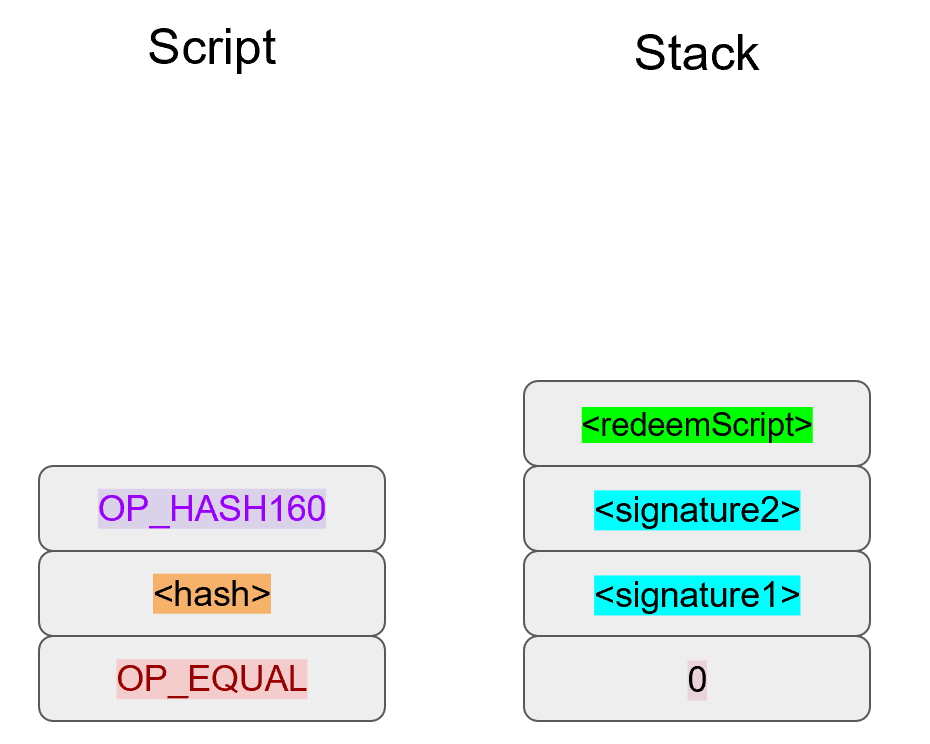

OP_HASH160 will hash the RedeemScript, which will make the stack look like this:

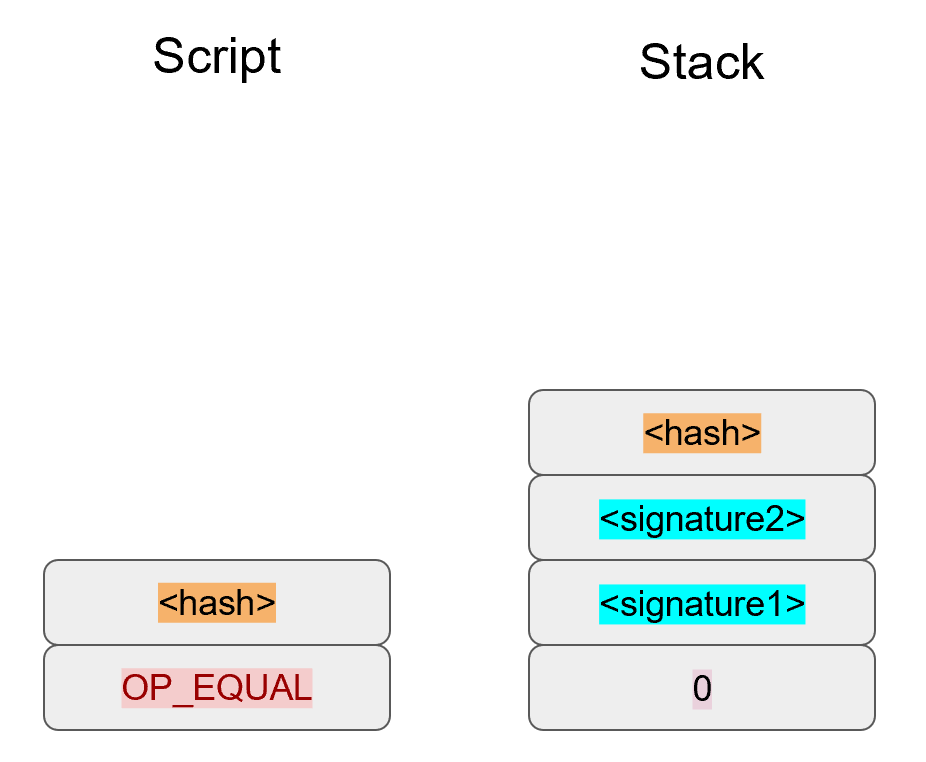

The 20-byte hash will be pushed on the stack:

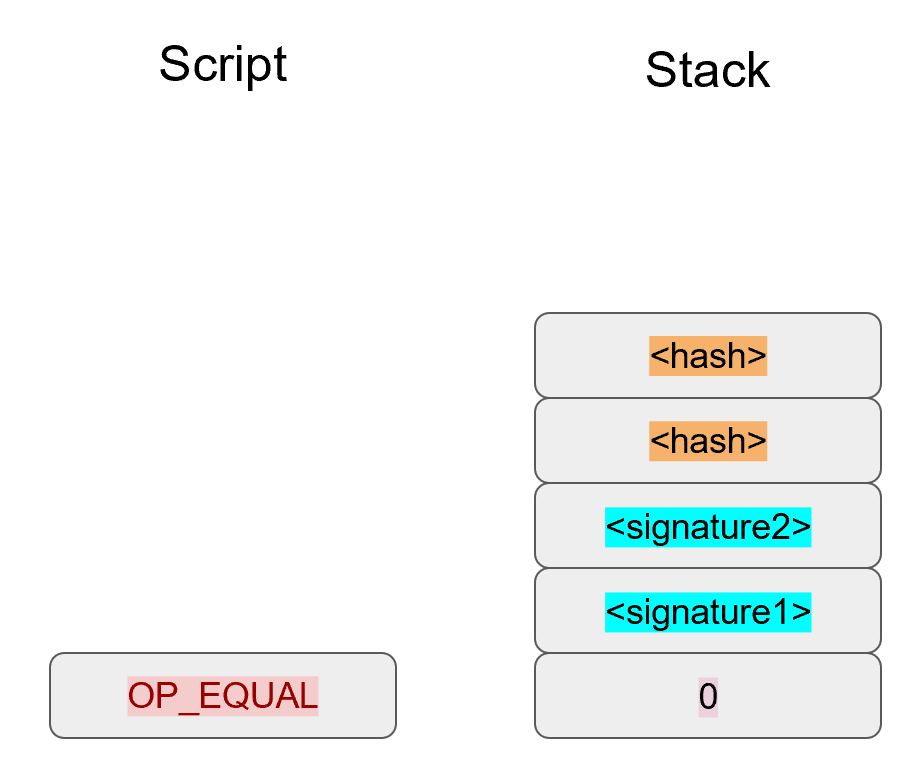

And finally, OP_EQUAL will compare the top two elements. If the software checking this transaction is pre-BIP0016, we would end up with this:

This would end evaluation for pre-BIP0016 nodes and the result would be valid, assuming the hashes are equal.

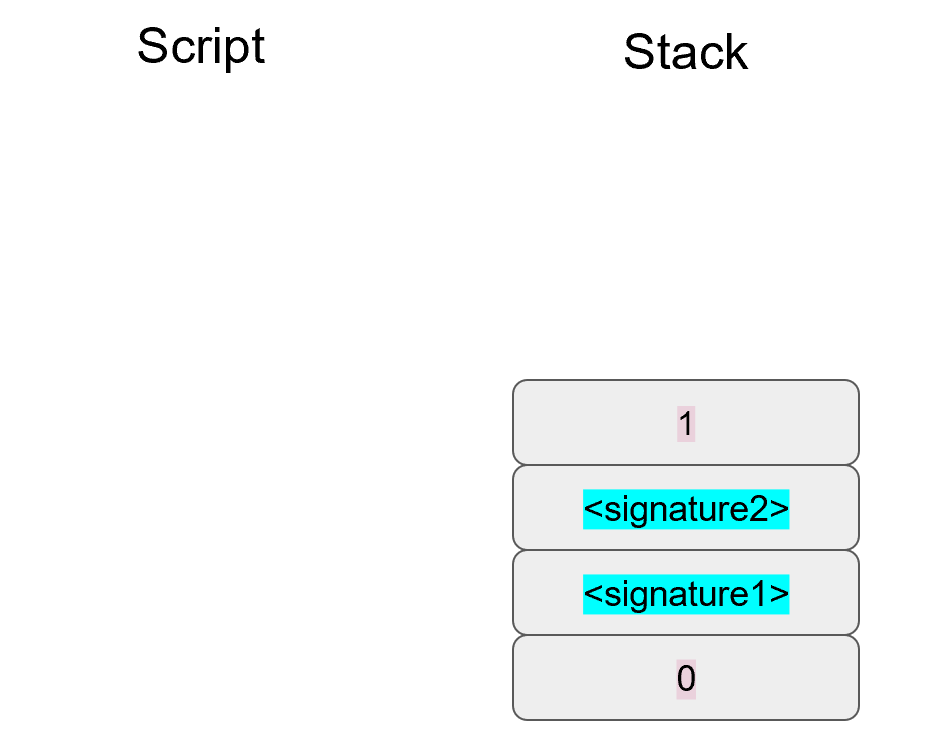

On the other hand, BIP0016 nodes (most nodes on the network are BIP0016 nodes now), will now take the RedeemScript and parse that as Script instructions:

These now go into the Script column instead of a 1 being pushed like so:

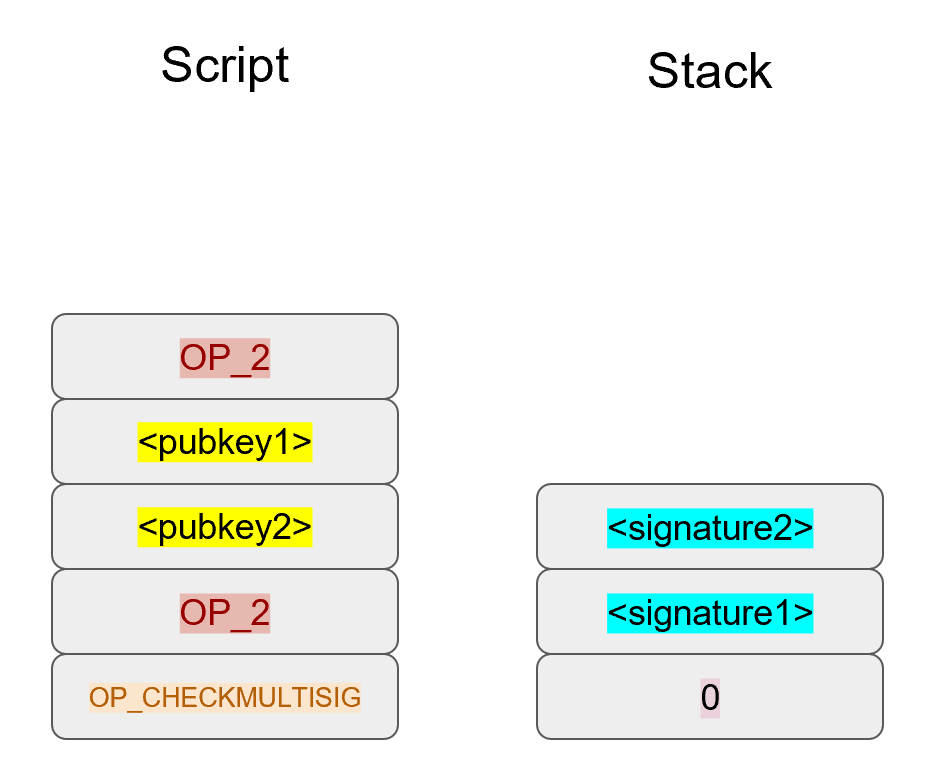

OP_2 pushes a 2 on the stack, the pubkeys are also pushed:

OP_CHECKMULTISIG consumes m+n+3 elements, which is the entire stack, and we end the same way we did Bare Multisig.

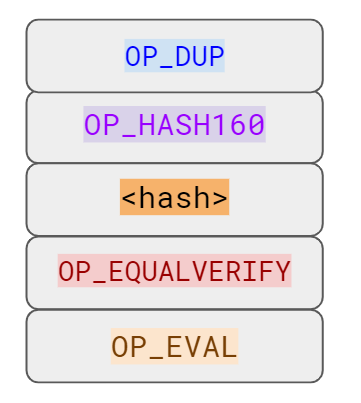

This is a bit hacky and there’s a lot of special-cased code in Bitcoin to handle this. Why didn’t the core devs do something a lot less hacky and more intuitive? Well, it turns out that there was indeed another proposal BIP0012 which used something called OP_EVAL, which would have been a lot more elegant. A Script like this would have sufficed:

OP_EVAL would consume the top element of the stack and interpret that as Script instructions to be put into the Script column.

Unfortunately, this much more elegant solution comes with an unwanted side-effect, namely Turing-completeness. Turing completeness is undesirable as it not only makes the security of a smart contract much harder to guarantee (see Chapter 6). Thus, the more hacky, but less vulnerable option of special-casing was chosen in BIP0016. BIP0016 or p2sh was implemented in 2011 and continues to be a part of the network today.

We now need to special case the particular sequence of redeem_script, OP_HASH160, 20-byte-hash and OP_EQUAL. This requires that our evaluate method in script.py will have to be changed:

def evaluate(self, z):

insts = self.instructions[:]

stack = []

altstack = []

while len(insts) > 0:

inst = insts.pop(0)

if type(inst) == int:

...

else:

stack.append(inst)

if len(insts) == 3 and insts[0] == 0xa9 \

and type(insts[1]) == bytes and len(insts[1]) == 20 \

and insts[2] == 0x87: # (1)

insts.pop() # (2)

h160 = insts.pop()

insts.pop()

if not op_hash160(stack): # (3)

return False

stack.append(h160)

if not op_equal(stack):

return False

if not op_verify(stack): # (4)

print('bad p2sh h160')

return False

redeem_script = encode_varint(len(inst)) + inst # (5)

stream = BytesIO(redeem_script)

insts.extend(Script.parse(stream).instructions) # (6)

if len(stack) == 0:

return False

if stack.pop() == b'':

return False

return True-

0xa9isOP_HASH160,0x87isOP_EQUAL. We’re checking here that the next 3 instructions are exactly the pattern we’re looking for. -

We know that this is

OP_HASH160, so we just pop it off. Similarly, we know the next one is the 20-byte hash value and the third item isOP_EQUAL, which is what we tested for in the if statement above it. -

We run the

OP_HASH160, 20-byte hash push on the stack andOP_EQUALas normal. -

There should be a 1 remaining, which is what op_verify checks for (

OP_VERIFYconsumes 1 element and does not put anything back). -

Because we want to parse the RedeemScript, we need to prepend the length.

-

We can now extend our instruction set with the parsed instructions from the RedeemScript.

The nice thing about p2sh is that the RedeemScript can be as long as the largest single element from OP_PUSHDATA2, which is 520 bytes. Multisig is just one possibility. You can have Scripts that define more complicated logic like "2 of 3 of these keys or 5 of 7 of these other keys". The main feature of p2sh is that it’s very flexible and at the same time reduces the UTXO set size by pushing the burden of storing part of the Script back to the user.

As we’ll see in Chapter 13, p2sh is used to make Segwit backwards compatible.

P2sh addresses have a very similar structure to p2pkh addresses. Namely, 20 bytes are being encoded with a particular prefix and a checksum that helps identify if any of the characters are encoded wrong in Base58.

Specifically, p2sh uses the 0x05 byte on mainnet which translates to addresses that start with a 3 in base58. This can be done using the encode_base58_checksum function from helper.py.

>>> from helper import encode_base58_checksum

>>> h160 = bytes.fromhex('74d691da1574e6b3c192ecfb52cc8984ee7b6c56')

>>> print(encode_base58_checksum(b'\x05' + h160))

3CLoMMyuoDQTPRD3XYZtCvgvkadrAdvdXhThe testnet prefix is the 0xc4 byte which creates addresses that start with a 2 in base58.

Write two functions in h160_to_p2pkh_address and h160_to_p2sh_address that convert a 20-byte hash160 into a p2pkh and p2sh address respectively.

As with p2pkh, one of the tricky aspects of p2sh is verifying the signatures. You would think that the p2sh signature verification would be the same as the p2pkh process covered in Chapter 7, but unfortunately, that’s not the case.

Unlike p2pkh where there’s only 1 signature and 1 public key, we have some number of pubkeys (in SEC format in the RedeemScript) and some equal or smaller number of signatures (in DER format in the ScriptSig). Thankfully, signatures have to be in the same order as the pubkeys or the signatures are not considered valid.

Once we have a particular signature and public key, we still need the signature hash, or z to figure out whether the signature is valid.

Once again, finding the signature hash is the most difficult part of the p2sh signature validation process and we’ll now proceed to cover this in detail.

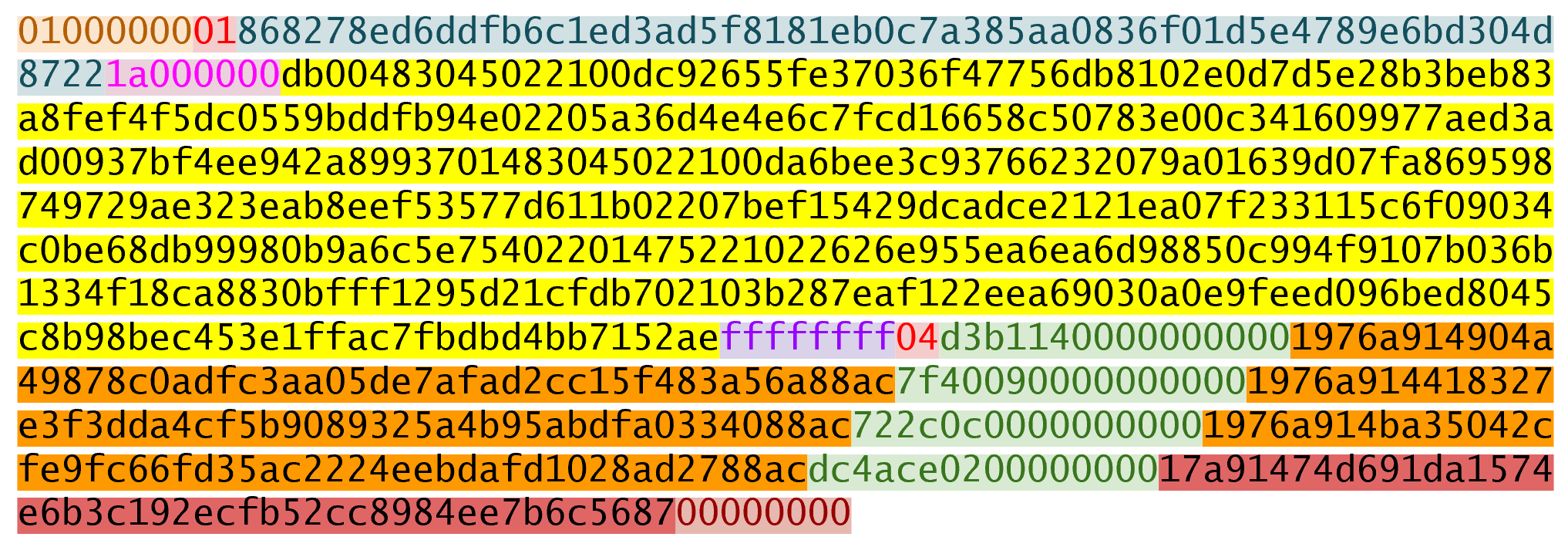

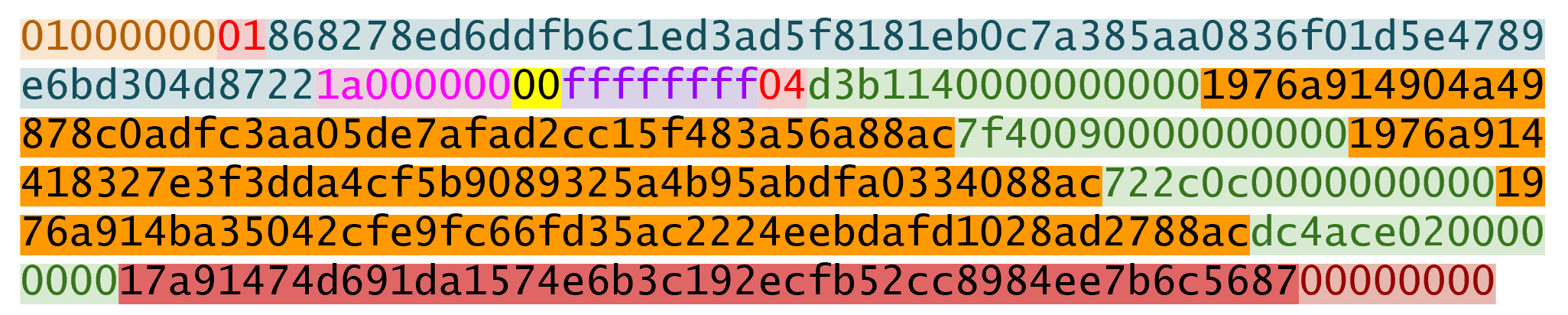

The first step is to empty all the ScriptSigs when checking the signature. The same procedure is used for creating the signature, except the ScriptSigs are usually already empty.

Each p2sh input has a RedeemScript. We take this RedeemScript and put that in place of the empty ScriptSig. This is different from p2pkh in that it’s not the ScriptPubKey.

Lastly, we add a 4-byte hash type to the end. This is the same as in p2pkh.

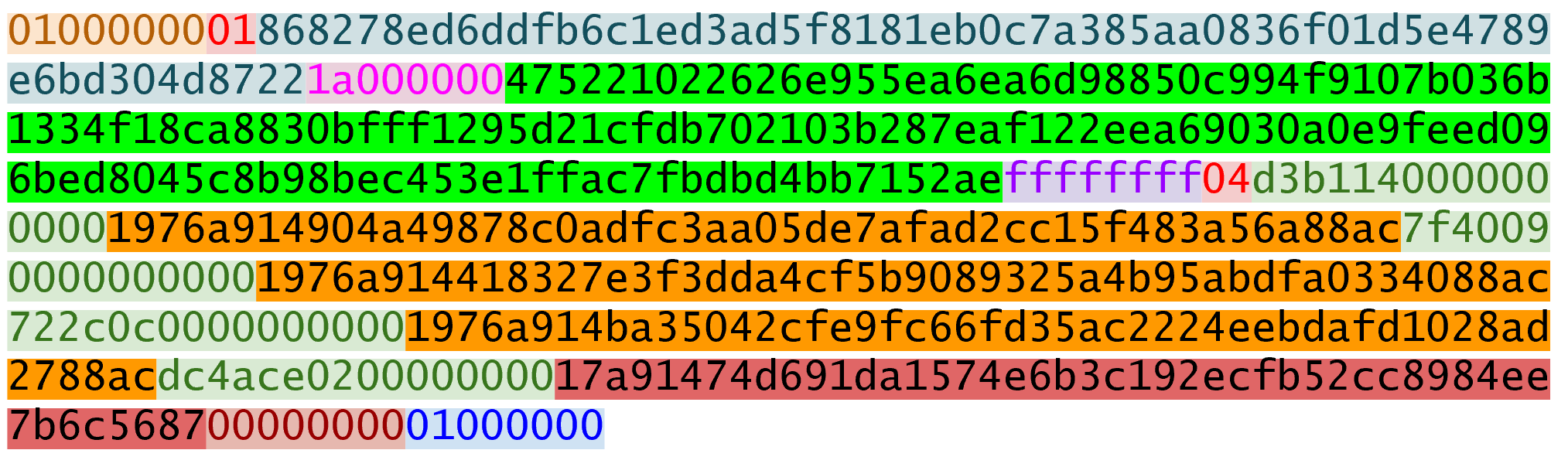

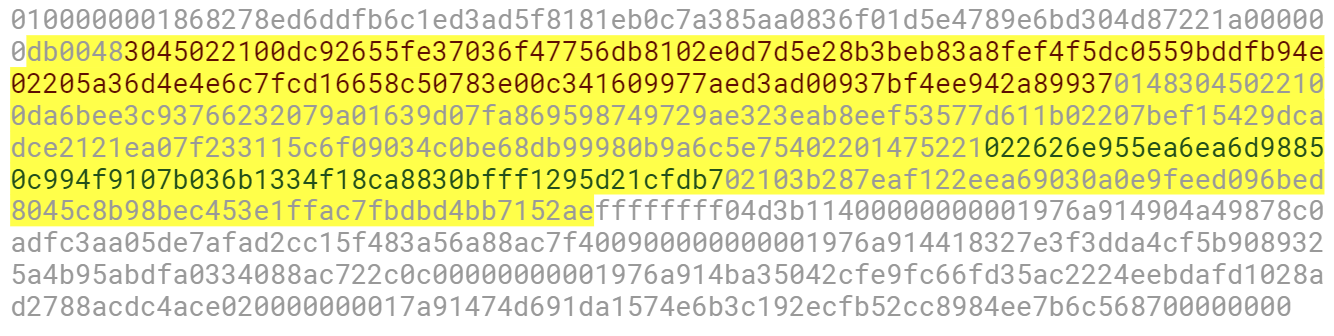

The integer corresponding to SIGHASH_ALL is 1 and this has to be encoded in Little-Endian over 4 bytes, which makes the transaction look like this:

The hash256 of this interpreted as a Big-Endian integer is our z. The code for getting our signature hash, or z, looks like this:

>>> from helper import hash256

>>> modified_tx = bytes.fromhex('01000000...01000000')

>>> s256 = hash256(modified_tx)

>>> z = int.from_bytes(s256, 'big')

>>> print(hex(z))

0xe71bfa115715d6fd33796948126f40a8cdd39f187e4afb03896795189fe1423cNow that we have our z, we can grab the SEC public key and DER signature from the ScriptSig and RedeemScript:

>>> from ecc import S256Point, Signature

>>> from helper import hash256

>>> modified_tx = bytes.fromhex('01000000...01000000')

>>> d256 = hash256(modified_tx)

>>> z = int.from_bytes(d256, 'big') # (1)

>>> sec = bytes.fromhex('0226...70')

>>> der = bytes.fromhex('3045....37')

>>> point = S256Point.parse(sec)

>>> sig = Signature.parse(der)

True-

zis from the code above

We’ve validated 1 of the 2 signatures that are needed to unlock this p2sh multisig.