| title |

|---|

Java API Programming Guide |

Analysis programs in Flink are regular Java programs that implement transformations on data sets (e.g., filtering, mapping, joining, grouping). The data sets are initially created from certain sources (e.g., by reading files, or from collections). Results are returned via sinks, which may for example write the data to (distributed) files, or to standard output (for example the command line terminal). Flink programs run in a variety of contexts, standalone, or embedded in other programs. The execution can happen in a local JVM, or on clusters of many machines.

In order to create your own Flink program, we encourage you to start with the program skeleton and gradually add your own transformations. The remaining sections act as references for additional operations and advanced features.

The following program is a complete, working example of WordCount. You can copy & paste the code to run it locally. You only have to include Flink's Java API library into your project (see Section Linking with Flink) and specify the imports. Then you are ready to go!

public class WordCountExample {

public static void main(String[] args) throws Exception {

final ExecutionEnvironment env = ExecutionEnvironment.getExecutionEnvironment();

DataSet<String> text = env.fromElements(

"Who's there?",

"I think I hear them. Stand, ho! Who's there?");

DataSet<Tuple2<String, Integer>> wordCounts = text

.flatMap(new LineSplitter())

.groupBy(0)

.sum(1);

wordCounts.print();

env.execute("Word Count Example");

}

public static class LineSplitter implements FlatMapFunction<String, Tuple2<String, Integer>> {

@Override

public void flatMap(String line, Collector<Tuple2<String, Integer>> out) {

for (String word : line.split(" ")) {

out.collect(new Tuple2<String, Integer>(word, 1));

}

}

}

}To write programs with Flink, you need to include Flink’s Java API library in your project.

The simplest way to do this is to use the quickstart scripts. They create a blank project from a template (a Maven Archetype), which sets up everything for you. To manually create the project, you can use the archetype and create a project by calling:

mvn archetype:generate /

-DarchetypeGroupId=org.apache.flink/

-DarchetypeArtifactId=flink-quickstart-java /

-DarchetypeVersion={{site.FLINK_VERSION_STABLE }}If you want to add Flink to an existing Maven project, add the following entry to your dependencies section in the pom.xml file of your project:

<dependency>

<groupId>org.apache.flink</groupId>

<artifactId>flink-java</artifactId>

<version>{{site.FLINK_VERSION_STABLE }}</version>

</dependency>

<dependency>

<groupId>org.apache.flink</groupId>

<artifactId>flink-clients</artifactId>

<version>{{site.FLINK_VERSION_STABLE }}</version>

</dependency>If you are using Flink together with Hadoop, the version of the dependency may vary depending on the version of Hadoop (or more specifically, HDFS) that you want to use Flink with. Please refer to the downloads page for a list of available versions, and instructions on how to link with custom versions of Hadoop.

In order to link against the latest SNAPSHOT versions of the code, please follow this guide.

The flink-clients dependency is only necessary to invoke the Flink program locally (for example to run it standalone for testing and debugging). If you intend to only export the program as a JAR file and run it on a cluster, you can skip that dependency.

As we already saw in the example, Flink programs look like regular Java

programs with a main() method. Each program consists of the same basic parts:

- Obtain an

ExecutionEnvironment, - Load/create the initial data,

- Specify transformations on this data,

- Specify where to put the results of your computations, and

- Execute your program.

We will now give an overview of each of those steps but please refer

to the respective sections for more details. Note that all {% gh_link /flink-java/src/main/java/org/apache/flink/api/java "core classes of the Java API" %} are found in the package org.apache.flink.api.java.

The ExecutionEnvironment is the basis for all Flink programs. You can

obtain one using these static methods on class ExecutionEnvironment:

getExecutionEnvironment()

createLocalEnvironment()

createLocalEnvironment(int degreeOfParallelism)

createRemoteEnvironment(String host, int port, String... jarFiles)

createRemoteEnvironment(String host, int port, int degreeOfParallelism, String... jarFiles)Typically, you only need to use getExecutionEnvironment(), since this

will do the right thing depending on the context: if you are executing

your program inside an IDE or as a regular Java program it will create

a local environment that will execute your program on your local machine. If

you created a JAR file from you program, and invoke it through the command line

or the web interface,

the Flink cluster manager will

execute your main method and getExecutionEnvironment() will return

an execution environment for executing your program on a cluster.

For specifying data sources the execution environment has several methods to read from files using various methods: you can just read them line by line, as CSV files, or using completely custom data input formats. To just read a text file as a sequence of lines, you can use:

final ExecutionEnvironment env = ExecutionEnvironment.getExecutionEnvironment();

DataSet<String> text = env.readTextFile("file:///path/to/file");This will give you a DataSet on which you can then apply transformations. For

more information on data sources and input formats, please refer to

Data Sources.

Once you have a DataSet you can apply transformations to create a new

DataSet which you can then write to a file, transform again, or

combine with other DataSets. You apply transformations by calling

methods on DataSet with your own custom transformation function. For example,

a map transformation looks like this:

DataSet<String> input = ...;

DataSet<Integer> tokenized = text.map(new MapFunction<String, Integer>() {

@Override

public Integer map(String value) {

return Integer.parseInt(value);

}

});This will create a new DataSet by converting every String in the original

set to an Integer. For more information and a list of all the transformations,

please refer to Transformations.

Once you have a DataSet that needs to be written to disk you call one

of these methods on DataSet:

writeAsText(String path)

writeAsCsv(String path)

write(FileOutputFormat<T> outputFormat, String filePath)

print()The last method is only useful for developing/debugging on a local machine,

it will output the contents of the DataSet to standard output. (Note that in

a cluster, the result goes to the standard out stream of the cluster nodes and ends

up in the .out files of the workers).

The first two do as the name suggests, the third one can be used to specify a

custom data output format. Keep in mind, that these calls do not actually

write to a file yet. Only when your program is completely specified and you

call the execute method on your ExecutionEnvironment are all the

transformations executed and is data written to disk. Please refer

to Data Sinks for more information on writing to files and also

about custom data output formats.

Once you specified the complete program you need to call execute on

the ExecutionEnvironment. This will either execute on your local

machine or submit your program for execution on a cluster, depending on

how you created the execution environment.

Back to top

All Flink programs are executed lazily: When the program's main method is executed, the data loading and transformations do not happen directly. Rather, each operation is created and added to the program's plan. The operations are actually executed when one of the execute() methods is invoked on the ExecutionEnvironment object. Whether the program is executed locally or on a cluster depends on the environment of the program.

The lazy evaluation lets you construct sophisticated programs that Flink executes as one holistically planned unit. Back to top

Data transformations transform one or more DataSets into a new DataSet. Programs can combine multiple transformations into sophisticated assemblies.

This section gives a brief overview of the available transformations. The transformations documentation has full description of all transformations with examples.

<tr>

<td><strong>FlatMap</strong></td>

<td>

<p>Takes one element and produces zero, one, or more elements. </p>

{% highlight java %} data.flatMap(new FlatMapFunction<String, String>() { public void flatMap(String value, Collector out) { for (String s : value.split(" ")) { out.collect(s); } } }); {% endhighlight %}

<tr>

<td><strong>MapPartition</strong></td>

<td>

<p>Transforms a parallel partition in a single function call. The function get the partition as an `Iterable` stream and

can produce an arbitrary number of result values. The number of elements in each partition depends on the degree-of-parallelism

and previous operations.</p>

{% highlight java %} data.mapPartition(new MapPartitionFunction<String, Long>() { public void mapPartition(Iterable values, Collector out) { long c = 0; for (String s : values) { c++; } out.collect(c); } }); {% endhighlight %}

<tr>

<td><strong>Filter</strong></td>

<td>

<p>Evaluates a boolean function for each element and retains those for which the function returns true.</p>

{% highlight java %} data.filter(new FilterFunction() { public boolean filter(Integer value) { return value > 1000; } }); {% endhighlight %}

<tr>

<td><strong>Reduce</strong></td>

<td>

<p>Combines a group of elements into a single element by repeatedly combining two elements into one.

Reduce may be applied on a full data set, or on a grouped data set.</p>

{% highlight java %} data.reduce(new ReduceFunction { public Integer reduce(Integer a, Integer b) { return a + b; } }); {% endhighlight %}

<tr>

<td><strong>ReduceGroup</strong></td>

<td>

<p>Combines a group of elements into one or more elements. ReduceGroup may be applied on a full data set, or on a grouped data set.</p>

{% highlight java %} data.reduceGroup(new GroupReduceFunction<Integer, Integer> { public void reduceGroup(Iterable values, Collector out) { int prefixSum = 0; for (Integer i : values) { prefixSum += i; out.collect(prefixSum); } } }); {% endhighlight %}

<tr>

<td><strong>Aggregate</strong></td>

<td>

<p>Aggregates a group of values into a single value. Aggregation functions can be thought of as built-in reduce functions. Aggregate may be applied on a full data set, or on a grouped data set.</p>

{% highlight java %} Dataset<Tuple3<Integer, String, Double>> input = // [...] DataSet<Tuple3<Integer, String, Double>> output = input.aggregate(SUM, 0).and(MIN, 2); {% endhighlight %}

You can also use short-hand syntax for minimum, maximum, and sum aggregations.

{% highlight java %} Dataset<Tuple3<Integer, String, Double>> input = // [...] DataSet<Tuple3<Integer, String, Double>> output = input.sum(0).andMin(2); {% endhighlight %}</tr>

<td><strong>Join</strong></td>

<td>

Joins two data sets by creating all pairs of elements that are equal on their keys. Optionally uses a JoinFunction to turn the pair of elements into a single element, or a FlatJoinFunction to turn the pair of elements into arbitararily many (including none) elements. See <a href="#keys">keys</a> on how to define join keys.

{% highlight java %} result = input1.join(input2) .where(0) // key of the first input (tuple field 0) .equalTo(1); // key of the second input (tuple field 1) {% endhighlight %}

<tr>

<td><strong>CoGroup</strong></td>

<td>

<p>The two-dimensional variant of the reduce operation. Groups each input on one or more fields and then joins the groups. The transformation function is called per pair of groups. See <a href="#keys">keys</a> on how to define coGroup keys.</p>

{% highlight java %} data1.coGroup(data2) .where(0) .equalTo(1) .with(new CoGroupFunction<String, String, String>() { public void coGroup(Iterable in1, Iterable in2, Collector out) { out.collect(...); } }); {% endhighlight %}

<tr>

<td><strong>Cross</strong></td>

<td>

<p>Builds the Cartesian product (cross product) of two inputs, creating all pairs of elements. Optionally uses a CrossFunction to turn the pair of elements into a single element</p>

{% highlight java %} DataSet data1 = // [...] DataSet data2 = // [...] DataSet<Tuple2<Integer, String>> result = data1.cross(data2); {% endhighlight %}

| Transformation | Description |

|---|---|

| Map |

Takes one element and produces one element. {% highlight java %} data.map(new MapFunction() { public Integer map(String value) { return Integer.parseInt(value); } }); {% endhighlight %} |

| Union |

Produces the union of two data sets. This operation happens implicitly if more than one data set is used for a specific function input. {% highlight java %} DataSet data1 = // [...] DataSet data2 = // [...] DataSet result = data1.union(data2); {% endhighlight %} |

The following transformations are available on data sets of Tuples:

| Transformation | Description |

|---|---|

| Project |

Selects a subset of fields from the tuples {% highlight java %} DataSet> in = // [...] DataSet> out = in.project(2,0).types(String.class, Integer.class); {% endhighlight %} |

The parallelism of a transformation can be defined by setParallelism(int). name(String) assigns a custom name to a transformation which is helpful for debugging. The same is possible for Data Sources and Data Sinks.

Some transformations (join, coGroup) require that a key is defined on its argument DataSets, and other transformations (Reduce, GroupReduce, Aggregate) allow that the DataSet is grouped on a key before they are applied.

A DataSet is grouped as {% highlight java %} DataSet<...> input = // [...] DataSet<...> reduced = input .groupBy(/define key here/) .reduceGroup(/do something/); {% endhighlight %}

The data model of Flink is not based on key-value pairs. Therefore, you do not need to physically pack the data set types into keys and values. Keys are "virtual": they are defined as functions over the actual data to guide the grouping operator.

The simplest case is grouping a data set of Tuples on one or more fields of the Tuple: {% highlight java %} DataSet<Tuple3<Integer,String,Long>> input = // [...] DataSet<Tuple3<Integer,String,Long> grouped = input .groupBy(0) .reduceGroup(/do something/); {% endhighlight %}

The data set is grouped on the first field of the tuples (the one of Integer type). The GroupReduceFunction will thus receive groups with the same value of the first field.

{% highlight java %} DataSet<Tuple3<Integer,String,Long>> input = // [...] DataSet<Tuple3<Integer,String,Long> grouped = input .groupBy(0,1) .reduce(/do something/); {% endhighlight %}

The data set is grouped on the composite key consisting of the first and the second fields, therefore the GroupReduceFuntion will receive groups with the same value for both fields.

In general, key definition is done via a "key selector" function, which takes as argument one dataset element and returns a key of an arbitrary data type by performing an arbitrary computation on this element. For example: {% highlight java %} // some ordinary POJO public class WC {public String word; public int count;} DataSet words = // [...] DataSet wordCounts = words .groupBy( new KeySelector<WC, String>() { public String getKey(WC wc) { return wc.word; } }) .reduce(/do something/); {% endhighlight %}

Remember that keys are not only used for grouping, but also joining and matching data sets: {% highlight java %} // some POJO public class Rating { public String name; public String category; public int points; } DataSet ratings = // [...] DataSet<Tuple2<String, Double>> weights = // [...] DataSet<Tuple2<String, Double>> weightedRatings = ratings.join(weights)

// key of the first input

.where(new KeySelector<Rating, String>() {

public String getKey(Rating r) { return r.category; }

})

// key of the second input

.equalTo(new KeySelector<Tuple2<String, Double>, String>() {

public String getKey(Tuple2<String, Double> t) { return t.f0; }

});

{% endhighlight %}

You can define a user-defined function and pass it to the DataSet transformations in several ways:

The most basic way is to implement one of the provided interfaces:

{% highlight java %} class MyMapFunction implements MapFunction<String, Integer> { public Integer map(String value) { return Integer.parseInt(value); } }); data.map (new MyMapFunction()); {% endhighlight %}

You can pass a function as an anonmymous class: {% highlight java %} data.map(new MapFunction<String, Integer> () { public Integer map(String value) { return Integer.parseInt(value); } }); {% endhighlight %}

Warning: Lambdas are currently only supported for filter and reduce transformations

{% highlight java %} DataSet data = // [...] data.filter(s -> s.startsWith("http://")); {% endhighlight %}

{% highlight java %} DataSet data = // [...] data.reduce((i1,i2) -> i1 + i2); {% endhighlight %}

All transformations that take as argument a user-defined function can

instead take as argument a rich function. For example, instead of

{% highlight java %}

class MyMapFunction implements MapFunction<String, Integer> {

public Integer map(String value) { return Integer.parseInt(value); }

});

{% endhighlight %}

you can write

{% highlight java %}

class MyMapFunction extends RichMapFunction<String, Integer> {

public Integer map(String value) { return Integer.parseInt(value); }

});

{% endhighlight %}

and pass the function as usual to a map transformation:

{% highlight java %}

data.map(new MyMapFunction());

{% endhighlight %}

Rich functions can also be defined as an anonymous class: {% highlight java %} data.map (new RichMapFunction<String, Integer>() { public Integer map(String value) { return Integer.parseInt(value); } }); {% endhighlight %}

Rich functions provide, in addition to the user-defined function (map,

reduce, etc), four methods: open, close, getRuntimeContext, and

setRuntimeContext. These are useful for creating and finalizing

local state, accessing broadcast variables (see

Broadcast Variables, and for accessing runtime

information such as accumulators and counters (see

Accumulators and Counters, and information

on iterations (see Iterations).

In particular for the reduceGroup transformation, using a rich

function is the only way to define an optional combine function. See

the

transformations documentation

for a complete example.

The Java API is strongly typed: All data sets and transformations accept typed elements. This catches type errors very early and supports safe refactoring of programs. The API supports various different data types for the input and output of operators. Both DataSet and functions like MapFunction, ReduceFunction, etc. are parameterized with data types using Java generics in order to ensure type-safety.

There are four different categories of data types, which are treated slightly different:

- Regular Types

- Tuples

- Values

- Hadoop Writables

Out of the box, the Java API supports all common basic Java types: Byte, Short, Integer, Long, Float, Double, Boolean, Character, String.

Furthermore, you can use the vast majority of custom Java classes. Restrictions apply to classes containing fields that cannot be serialized, like File pointers, I/O streams, or other native resources. Classes that follow the Java Beans conventions work well in general. The following defines a simple example class to illustrate how you can use custom classes:

public class WordWithCount {

public String word;

public int count;

public WordCount() {}

public WordCount(String word, int count) {

this.word = word;

this.count = count;

}

}You can use all of those types to parameterize DataSet and function implementations, e.g. DataSet<String> for a String data set or MapFunction<String, Integer> for a mapper from String to Integer.

// using a basic data type

DataSet<String> numbers = env.fromElements("1", "2");

numbers.map(new MapFunction<String, Integer>() {

@Override

public String map(String value) throws Exception {

return Integer.parseInt(value);

}

});

// using a custom class

DataSet<WordCount> wordCounts = env.fromElements(

new WordCount("hello", 1),

new WordCount("world", 2));

wordCounts.map(new MapFunction<WordCount, Integer>() {

@Override

public String map(WordCount value) throws Exception {

return value.count;

}

});When working with operators that require a Key for grouping or matching records

you need to implement a KeySelector for your custom type (see

Section Defining Keys).

wordCounts.groupBy(new KeySelector<WordCount, String>() {

public String getKey(WordCount v) {

return v.word;

}

}).reduce(new MyReduceFunction());You can use the Tuple classes for composite types. Tuples contain a fix number of fields of various types. The Java API provides classes from Tuple1 up to Tuple25. Every field of a tuple can be an arbitrary Flink type - including further tuples, resulting in nested tuples. Fields of a Tuple can be accessed directly using the fields tuple.f4, or using the generic getter method tuple.getField(int position). The field numbering starts with 0. Note that this stands in contrast to the Scala tuples, but it is more consistent with Java's general indexing.

DataSet<Tuple2<String, Integer>> wordCounts = env.fromElements(

new Tuple2<String, Integer>("hello", 1),

new Tuple2<String, Integer>("world", 2));

wordCounts.map(new MapFunction<Tuple2<String, Integer>, Integer>() {

@Override

public String map(Tuple2<String, Integer> value) throws Exception {

return value.f1;

}

});When working with operators that require a Key for grouping or matching records, Tuples let you simply specify the positions of the fields to be used as key. You can specify more than one position to use composite keys (see Section Data Transformations).

wordCounts

.groupBy(0)

.reduce(new MyReduceFunction());In order to access fields more intuitively and to generate more readable code, it is also possible to extend a subclass of Tuple. You can add getters and setters with custom names that delegate to the field positions. See this {% gh_link /flink-examples/flink-java-examples/src/main/java/org/apache/flink/example/java/relational/TPCHQuery3.java "example" %} for an illustration how to make use of that mechanism.

Value types describe their serialization and deserialization manually. Instead of going through a general purpose serialization framework, they provide custom code for those operations by means implementing the org.apache.flinktypes.Value interface with the methods read and write. Using a Value type is reasonable when general purpose serialization would be highly inefficient. An example would be a data type that implements a sparse vector of elements as an array. Knowing that the array is mostly zero, one can use a special encoding for the non-zero elements, while the general purpose serialization would simply write all array elements.

The org.apache.flinktypes.CopyableValue interface supports manual internal cloning logic in a similar way.

Flink comes with pre-defined Value types that correspond to Java's basic data types. (ByteValue, ShortValue, IntValue, LongValue, FloatValue, DoubleValue, StringValue, CharValue, BooleanValue). These Value types act as mutable variants of the basic data types: Their value can be altered, allowing programmers to reuse objects and take pressure off the garbage collector.

You can use types that implement the org.apache.hadoop.Writable interface. The serialization logic defined in the write()and readFields() methods will be used for serialization.

The Java compiler throws away much of the generic type information after the compilation. This is known as type erasure in Java. It means that at runtime, an instance of an object does not know its generic type any more. For example, instances of DataSet<String> and DataSet<Long> look the same to the JVM.

Flink requires type information at the time when it prepares the program for execution (when the main method of the program is called). The Flink Java API tries to reconstruct the type information that was thrown away in various ways and store it explicitly in the data sets and operators. You can retrieve the type via DataSet.getType(). The method returns an instance of TypeInformation, which is Flink's internal way of representing types.

The type inference has its limits and needs the "cooperation" of the programmer in some cases. Examples for that are methods that create data sets from collections, such as ExecutionEnvironment.fromCollection(), where you can pass an argument that describes the type. But also generic functions like MapFunction<I, O> may need extra type information.

The {% gh_link /flink-java/src/main/java/org/apache/flink/api/java/typeutils/ResultTypeQueryable.java "ResultTypeQueryable" %} interface can be implemented by input formats and functions to tell the API explicitly about their return type. The input types that the functions are invoked with can usually be inferred by the result types of the previous operations.

Data sources create the initial data sets, such as from files or from Java collections. The general mechanism of of creating data sets is abstracted behind an {% gh_link /flink-core/src/main/java/org/apache/flink/api/common/io/InputFormat.java "InputFormat" %}. Flink comes with several built-in formats to create data sets from common file formats. Many of them have shortcut methods on the ExecutionEnvironment.

File-based:

readTextFile(path)/TextInputFormat- Reads files line wise and returns them as Strings.readTextFileWithValue(path)/TextValueInputFormat- Reads files line wise and returns them as StringValues. StringValues are mutable strings.readCsvFile(path)/CsvInputFormat- Parses files of comma (or another char) delimited fields. Returns a DataSet of tuples. Supports the basic java types and their Value counterparts as field types.

Collection-based:

fromCollection(Collection)- Creates a data set from the Java Java.util.Collection. All elements in the collection must be of the same type.fromCollection(Iterator, Class)- Creates a data set from an iterator. The class specifies the data type of the elements returned by the iterator.fromElements(T ...)- Creates a data set from the given sequence of objects. All objects must be of the same type.fromParallelCollection(SplittableIterator, Class)- Creates a data set from an iterator, in parallel. The class specifies the data type of the elements returned by the iterator.generateSequence(from, to)- Generates the squence of numbers in the given interval, in parallel.

Generic:

createInput(path)/InputFormat- Accepts a generic input format.

Examples

ExecutionEnvironment env = ExecutionEnvironment.getExecutionEnvironment();

// read text file from local files system

DataSet<String> localLines = env.readTextFile("file:///path/to/my/textfile");

// read text file from a HDFS running at nnHost:nnPort

DataSet<String> hdfsLines = env.readTextFile("hdfs://nnHost:nnPort/path/to/my/textfile");

// read a CSV file with three fields

DataSet<Tuple3<Integer, String, Double>> csvInput = env.readCsvFile("hdfs:///the/CSV/file")

.types(Integer.class, String.class, Double.class);

// read a CSV file with five fields, taking only two of them

DataSet<Tuple2<String, Double>> csvInput = env.readCsvFile("hdfs:///the/CSV/file")

.includeFields("10010") // take the first and the fourth fild

.types(String.class, Double.class);

// create a set from some given elements

DataSet<String> value = env.fromElements("Foo", "bar", "foobar", "fubar");

// generate a number sequence

DataSet<Long> numbers = env.generateSequence(1, 10000000);

// Read data from a relational database using the JDBC input format

DataSet<Tuple2<String, Integer> dbData =

env.createInput(

// create and configure input format

JDBCInputFormat.buildJDBCInputFormat()

.setDrivername("org.apache.derby.jdbc.EmbeddedDriver")

.setDBUrl("jdbc:derby:memory:persons")

.setQuery("select name, age from persons")

.finish(),

// specify type information for DataSet

new TupleTypeInfo(Tuple2.class, STRING_TYPE_INFO, INT_TYPE_INFO)

);

// Note: Flink's program compiler needs to infer the data types of the data items which are returned by an InputFormat. If this information cannot be automatically inferred, it is necessary to manually provide the type information as shown in the examples above.Data sinks consume DataSets and are used to store or return them. Data sink operations are described using an {% gh_link /flink-core/src/main/java/org/apache/flink/api/common/io/OutputFormat.java "OutputFormat" %}. Flink comes with a variety of built-in output formats that are encapsulated behind operations on the DataSet type:

writeAsText()/TextOuputFormat- Writes elements line-wise as Strings. The Strings are obtained by calling the toString() method of each element.writeAsFormattedText()/TextOutputFormat- Write elements line-wise as Strings. The Strings are obtained by calling a user-defined format() method for each element.writeAsCsv/CsvOutputFormat- Writes tuples as comma-separated value files. Row and field delimiters are configurable. The value for each field comes from the toString() method of the objects.print()/printToErr()- Prints the toString() value of each element on the standard out / strandard error stream.write()/FileOutputFormat- Method and base class for custom file outputs. Supports custom object-to-bytes conversion.output()/OutputFormat- Most generic output method, for data sinks that are not file based (such as storing the result in a database).

A DataSet can be input to multiple operations. Programs can write or print a data set and at the same time run additional transformations on them.

Examples

Standard data sink methods:

// text data

DataSet<String> textData = // [...]

// write DataSet to a file on the local file system

textData.writeAsText("file:///my/result/on/localFS");

// write DataSet to a file on a HDFS with a namenode running at nnHost:nnPort

textData.writeAsText("hdfs://nnHost:nnPort/my/result/on/localFS");

// write DataSet to a file and overwrite the file if it exists

textData.writeAsText("file:///my/result/on/localFS", WriteMode.OVERWRITE);

// tuples as lines with pipe as the separator "a|b|c"

DataSet<Tuple3<String, Integer, Double>> values = // [...]

values.writeAsCsv("file:///path/to/the/result/file", "\n", "|");

// this writes tuples in the text formatting "(a, b, c)", rather than as CSV lines

values.writeAsText("file:///path/to/the/result/file");

// this wites values as strings using a user-defined TextFormatter object

values.writeAsFormattedText("file:///path/to/the/result/file", new TextFormatter<Tuple2<Integer, Integer>>() {

public String format (Tuple2<Integer, Integer> value) {

return value.f1 + " - " + value.f0;

}});Using a custom output format:

DataSet<Tuple3<String, Integer, Double>> myResult = [...]

// write Tuple DataSet to a relational database

myResult.output(

// build and configure OutputFormat

JDBCOutputFormat.buildJDBCOutputFormat()

.setDrivername("org.apache.derby.jdbc.EmbeddedDriver")

.setDBUrl("jdbc:derby:memory:persons")

.setQuery("insert into persons (name, age, height) values (?,?,?)")

.finish()

);Before running a data analysis program on a large data set in a distributed cluster, it is a good idea to make sure that the implemented algorithm works as desired. Hence, implementing data analysis programs is usually an incremental process of checking results, debugging, and improving.

Flink provides a few nice features to significantly ease the development process of data analysis programs by supporting local debugging from within an IDE, injection of test data, and collection of result data. This section give some hints how to ease the development of Flink programs.

A LocalEnvironment starts a Flink system within the same JVM process it was created in. If you start the LocalEnvironement from an IDE, you can set breakpoint in your code and easily debug your program.

A LocalEnvironment is created and used as follows:

final ExecutionEnvironment env = ExecutionEnvironment.createLocalEnvironment();

DataSet<String> lines = env.readTextFile(pathToTextFile);

// build your program

env.execute();Providing input for an analysis program and checking its output is cumbersome done by creating input files and reading output files. Flink features special data sources and sinks which are backed by Java collections to ease testing. Once a program has been tested, the sources and sinks can be easily replaced by sources and sinks that read from / write to external data stores such as HDFS.

Collection data sources can be used as follows:

final ExecutionEnvironment env = ExecutionEnvironment.createLocalEnvironment();

// Create a DataSet from a list of elements

DataSet<Integer> myInts = env.fromElements(1, 2, 3, 4, 5);

// Create a DataSet from any Java collection

List<Tuple2<String, Integer>> data = ...

DataSet<Tuple2<String, Integer>> myTuples = env.fromCollection(data);

// Create a DataSet from an Iterator

Iterator<Long> longIt = ...

DataSet<Long> myLongs = env.fromCollection(longIt, Long.class);Note: Currently, the collection data source requires that data types and iterators implement Serializable. Furthermore, collection data sources can not be executed in parallel (degree of parallelism = 1).

A collection data sink is specified as follows:

DataSet<Tuple2<String, Integer>> myResult = ...

List<Tuple2<String, Integer>> outData = new ArrayList<Tuple2<String, Integer>>();

myResult.output(new LocalCollectionOutputFormat(outData));Note: Currently, the collection data sink is restricted to local execution, as a debugging tool.

Iterations implement loops in Flink programs. The iteration operators encapsulate a part of the program and execute it repeatedly, feeding back the result of one iteration (the partial solution) into the next iteration. There are two types of iterations in Flink: BulkIteration and DeltaIteration.

This section provides quick examples on how to use both operators. Check out the Introduction to Iterations page for a more detailed introduction.

To create a BulkIteration call the iterate(int) method of the DataSet the iteration should start at. This will return an IterativeDataSet, which can be transformed with the regular operators. The single argument to the iterate call specifies the maximum number of iterations.

To specify the end of an iteration call the closeWith(DataSet) method on the IterativeDataSet to specify which transformation should be fed back to the next iteration. You can optionally specify a termination criterion with closeWith(DataSet, DataSet), which evaluates the second DataSet and terminates the iteration, if this DataSet is empty. If no termination criterion is specified, the iteration terminates after the given maximum number iterations.

The following example iteratively estimates the number Pi. The goal is to count the number of random points, which fall into the unit circle. In each iteration, a random point is picked. If this point lies inside the unit circle, we increment the count. Pi is then estimated as the resulting count divided by the number of iterations multiplied by 4.

{% highlight java %} final ExecutionEnvironment env = ExecutionEnvironment.getExecutionEnvironment();

// Create initial IterativeDataSet IterativeDataSet initial = env.fromElements(0).iterate(10000);

DataSet iteration = initial.map(new MapFunction<Integer, Integer>() { @Override public Integer map(Integer i) throws Exception { double x = Math.random(); double y = Math.random();

return i + ((x * x + y * y < 1) ? 1 : 0);

}

});

// Iteratively transform the IterativeDataSet DataSet count = initial.closeWith(iteration);

count.map(new MapFunction<Integer, Double>() { @Override public Double map(Integer count) throws Exception { return count / (double) 10000 * 4; } }).print();

env.execute("Iterative Pi Example"); {% endhighlight %}

You can also check out the {% gh_link /flink-examples/flink-java-examples/src/main/java/org/apache/flink/example/java/clustering/KMeans.java "K-Means example" %}, which uses a BulkIteration to cluster a set of unlabeled points.

Delta iterations exploit the fact that certain algorithms do not change every data point of the solution in each iteration.

In addition to the partial solution that is fed back (called workset) in every iteration, delta iterations maintain state across iterations (called solution set), which can be updated through deltas. The result of the iterative computation is the state after the last iteration. Please refer to the Introduction to Iterations for an overview of the basic principle of delta iterations.

Defining a DeltaIteration is similar to defining a BulkIteration. For delta iterations, two data sets form the input to each iteration (workset and solution set), and two data sets are produced as the result (new workset, solution set delta) in each iteration.

To create a DeltaIteration call the iterateDelta(DataSet, int, int) (or iterateDelta(DataSet, int, int[]) respectively). This method is called on the initial solution set. The arguments are the initial delta set, the maximum number of iterations and the key positions. The returned DeltaIteration object gives you access to the DataSets representing the workset and solution set via the methods iteration.getWorket() and iteration.getSolutionSet().

Below is an example for the syntax of a delta iteration

// read the initial data sets

DataSet<Tuple2<Long, Double>> initialSolutionSet = // [...]

DataSet<Tuple2<Long, Double>> initialDeltaSet = // [...]

int maxIterations = 100;

int keyPosition = 0;

DeltaIteration<Tuple2<Long, Double>, Tuple2<Long, Double>> iteration = initialSolutionSet

.iterateDelta(initialDeltaSet, maxIterations, keyPosition);

DataSet<Tuple2<Long, Double>> candidateUpdates = iteration.getWorkset()

.groupBy(1)

.reduceGroup(new ComputeCandidateChanges());

DataSet<Tuple2<Long, Double>> deltas = candidateUpdates

.join(iteration.getSolutionSet())

.where(0)

.equalTo(0)

.with(new CompareChangesToCurrent());

DataSet<Tuple2<Long, Double>> nextWorkset = deltas

.filter(new FilterByThreshold());

iteration.closeWith(deltas, nextWorkset)

.writeAsCsv(outputPath);Semantic Annotations give hints about the behavior of a function by telling the system which fields in the input are accessed and which are constant between input and output data of a function (copied but not modified). Semantic annotations are a powerful means to speed up execution, because they allow the system to reason about reusing sort orders or partitions across multiple operations. Using semantic annotations may eventually save the program from unnecessary data shuffling or unnecessary sorts.

Semantic annotations can be attached to functions through Java annotations, or passed as arguments when invoking a function on a DataSet. The following example illustrates that:

@ConstantFields("1")

public class DivideFirstbyTwo implements MapFunction<Tuple2<Integer, Integer>, Tuple2<Integer, Integer>> {

@Override

public Tuple2<Integer, Integer> map(Tuple2<Integer, Integer> value) {

value.f0 /= 2;

return value;

}

}The following annotations are currently available:

-

@ConstantFields: Declares constant fields (forwarded/copied) for functions with a single input data set (Map, Reduce, Filter, ...). -

@ConstantFieldsFirst: Declares constant fields (forwarded/copied) for functions with a two input data sets (Join, CoGroup, ...), with respect to the first input data set. -

@ConstantFieldsSecond: Declares constant fields (forwarded/copied) for functions with a two input data sets (Join, CoGroup, ...), with respect to the first second data set. -

@ConstantFieldsExcept: Declares that all fields are constant, except for the specified fields. Applicable to functions with a single input data set. -

@ConstantFieldsFirstExcept: Declares that all fields of the first input are constant, except for the specified fields. Applicable to functions with a two input data sets. -

@ConstantFieldsSecondExcept: Declares that all fields of the second input are constant, except for the specified fields. Applicable to functions with a two input data sets.

(Note: The system currently evaluated annotations only on Tuple data types. This will be extended in the next versions)

Note: It is important to be conservative when providing annotations. Only annotate fields, when they are always constant for every call to the function. Otherwise the system has incorrect assumptions about the execution and the execution may produce wrong results. If the behavior of the operator is not clearly predictable, no annotation should be provided.

Broadcast variables allow you to make a data set available to all parallel instances of an operation, in addition to the regular input of the operation. This is useful

for auxiliary data sets, or data-dependent parameterization. The data set will then be accessible at the operator as an Collection<T>.

- Broadcast: broadcast sets are registered by name via

withBroadcastSet(DataSet, String), and - Access: accessible via

getRuntimeContext().getBroadcastVariable(String)at the target operator.

// 1. The DataSet to be broadcasted

DataSet<Integer> toBroadcast = env.fromElements(1, 2, 3);

DataSet<String> data = env.fromElements("a", "b");

data.map(new MapFunction<String, String>() {

@Override

public void open(Configuration parameters) throws Exception {

// 3. Access the broadcasted DataSet as a Collection

Collection<Integer> broadcastSet = getRuntimeContext().getBroadcastVariable("broadcastSetName");

}

@Override

public String map(String value) throws Exception {

...

}

}).withBroadcastSet(toBroadcast, "broadcastSetName"); // 2. Broadcast the DataSetMake sure that the names (broadcastSetName in the previous example) match when registering and accessing broadcasted data sets. For a complete example program, have a look at

{% gh_link /flink-examples/flink-java-examples/src/main/java/org/apache/flink/example/java/clustering/KMeans.java#L96 "KMeans Algorithm" %}.

Note: As the content of broadcast variables is kept in-memory on each node, it should not become too large. For simpler things like scalar values you can simply make parameters part of the closure of a function, or use the withParameters(...) method to pass in a configuration.

As described in the program skeleton section, Flink programs can be executed on clusters by using the RemoteEnvironment. Alternatively, programs can be packaged into JAR Files (Java Archives) for execution. Packaging the program is a prerequisite to executing them through the command line interface or the web interface.

To support execution from a packaged JAR file via the command line or web interface, a program must use the environment obtained by ExecutionEnvironment.getExecutionEnvironment(). This environment will act as the cluster's environment when the JAR is submitted to the command line or web interface. If the Flink program is invoked differently than through these interfaces, the environment will act like a local environment.

To package the program, simply export all involved classes as a JAR file. The JAR file's manifest must point to the class that contains the program's entry point (the class with the public void main(String[]) method). The simplest way to do this is by putting the main-class entry into the manifest (such as main-class: org.apache.flinkexample.MyProgram). The main-class attribute is the same one that is used by the Java Virtual Machine to find the main method when executing a JAR files through the command java -jar pathToTheJarFile. Most IDEs offer to include that attribute automatically when exporting JAR files.

Additionally, the Java API supports packaging programs as Plans. This method resembles the way that the Scala API packages programs. Instead of defining a progam in the main method and calling execute() on the environment, plan packaging returns the Program Plan, which is a description of the program's data flow. To do that, the program must implement the org.apache.flinkapi.common.Program interface, defining the getPlan(String...) method. The strings passed to that method are the command line arguments. The program's plan can be created from the environment via the ExecutionEnvironment#createProgramPlan() method. When packaging the program's plan, the JAR manifest must point to the class implementing the org.apache.flinkapi.common.Program interface, instead of the class with the main method.

The overall procedure to invoke a packaged program is as follows:

- The JAR's manifest is searched for a main-class or program-class attribute. If both attributes are found, the program-class attribute takes precedence over the main-class attribute. Both the command line and the web interface support a parameter to pass the entry point class name manually for cases where the JAR manifest contains neither attribute.

- If the entry point class implements the

org.apache.flinkapi.common.Program, then the system calls thegetPlan(String...)method to obtain the program plan to execute. ThegetPlan(String...)method was the only possible way of defining a program in the Record API (see 0.4 docs) and is also supported in the new Java API. - If the entry point class does not implement the

org.apache.flinkapi.common.Programinterface, the system will invoke the main method of the class.

Accumulators are simple constructs with an add operation and a final accumulated result, which is available after the job ended.

The most straightforward accumulator is a counter: You can increment it using the Accumulator.add(V value) method. At the end of the job Flink will sum up (merge) all partial results and send the result to the client. Since accumulators are very easy to use, they can be useful during debugging or if you quickly want to find out more about your data.

Flink currently has the following built-in accumulators. Each of them implements the {% gh_link /flink-core/src/main/java/org/apache/flink/api/common/accumulators/Accumulator.java "Accumulator" %} interface.

- {% gh_link /flink-core/src/main/java/org/apache/flink/api/common/accumulators/IntCounter.java "IntCounter" %}, {% gh_link /flink-core/src/main/java/org/apache/flink/api/common/accumulators/LongCounter.java "LongCounter" %} and {% gh_link /flink-core/src/main/java/org/apache/flink/api/common/accumulators/DoubleCounter.java "DoubleCounter" %}: See below for an example using a counter.

- {% gh_link /flink-core/src/main/java/org/apache/flink/api/common/accumulators/Histogram.java "Histogram" %}: A histogram implementation for a discrete number of bins. Internally it is just a map from Integer to Integer. You can use this to compute distributions of values, e.g. the distribution of words-per-line for a word count program.

How to use accumulators:

First you have to create an accumulator object (here a counter) in the operator function where you want to use it. Operator function here refers to the (anonymous inner) class implementing the user defined code for an operator.

private IntCounter numLines = new IntCounter();

Second you have to register the accumulator object, typically in the open() method of the operator function. Here you also define the name.

getRuntimeContext().addAccumulator("num-lines", this.numLines);

You can now use the accumulator anywhere in the operator function, including in the open() and close() methods.

this.numLines.add(1);

The overall result will be stored in the JobExecutionResult object which is returned when running a job using the Java API (currently this only works if the execution waits for the completion of the job).

myJobExecutionResult.getAccumulatorResult("num-lines")

All accumulators share a single namespace per job. Thus you can use the same accumulator in different operator functions of your job. Flink will internally merge all accumulators with the same name.

A note on accumulators and iterations: Currently the result of accumulators is only available after the overall job ended. We plan to also make the result of the previous iteration available in the next iteration. You can use {% gh_link /flink-java/src/main/java/org/apache/flink/api/java/IterativeDataSet.java#L98 "Aggregators" %} to compute per-iteration statistics and base the termination of iterations on such statistics.

Custom accumulators:

To implement your own accumulator you simply have to write your implementation of the Accumulator interface. Feel free to create a pull request if you think your custom accumulator should be shipped with Flink.

You have the choice to implement either {% gh_link /flink-core/src/main/java/org/apache/flink/api/common/accumulators/Accumulator.java "Accumulator" %} or {% gh_link /flink-core/src/main/java/org/apache/flink/api/common/accumulators/SimpleAccumulator.java "SimpleAccumulator" %}. Accumulator<V,R> is most flexible: It defines a type V for the value to add, and a result type R for the final result. E.g. for a histogram, V is a number and R is a histogram. SimpleAccumulator is for the cases where both types are the same, e.g. for counters.

This section describes how the parallel execution of programs can be configured in Flink. A Flink program consists of multiple tasks (operators, data sources, and sinks). A task is split into several parallel instances for execution and each parallel instance processes a subset of the task's input data. The number of parallel instances of a task is called its parallelism or degree of parallelism (DOP).

The degree of parallelism of a task can be specified in Flink on different levels.

The parallelism of an individual operator, data source, or data sink can be defined by calling its setParallelism() method.

For example, the degree of parallelism of the Sum operator in the WordCount example program can be set to 5 as follows :

final ExecutionEnvironment env = ExecutionEnvironment.getExecutionEnvironment();

DataSet<String> text = [...]

DataSet<Tuple2<String, Integer>> wordCounts = text

.flatMap(new LineSplitter())

.groupBy(0)

.sum(1).setParallelism(5);

wordCounts.print();

env.execute("Word Count Example");Flink programs are executed in the context of an execution environmentt. An execution environment defines a default parallelism for all operators, data sources, and data sinks it executes. Execution environment parallelism can be overwritten by explicitly configuring the parallelism of an operator.

The default parallelism of an execution environment can be specified by calling the setDefaultLocalParallelism() method. To execute all operators, data sources, and data sinks of the WordCount example program with a parallelism of 3, set the default parallelism of the execution environment as follows:

final ExecutionEnvironment env = ExecutionEnvironment.getExecutionEnvironment();

env.setDegreeOfParallelism(3);

DataSet<String> text = [...]

DataSet<Tuple2<String, Integer>> wordCounts = [...]

wordCounts.print();

env.execute("Word Count Example");A system-wide default parallelism for all execution environments can be defined by setting the parallelization.degree.default property in ./conf/flink-conf.yaml. See the Configuration documentation for details.

Depending on various parameters such as data size or number of machines in the cluster, Flink's optimizer automatically chooses an execution strategy for your program. In many cases, it can be useful to know how exactly Flink will execute your program.

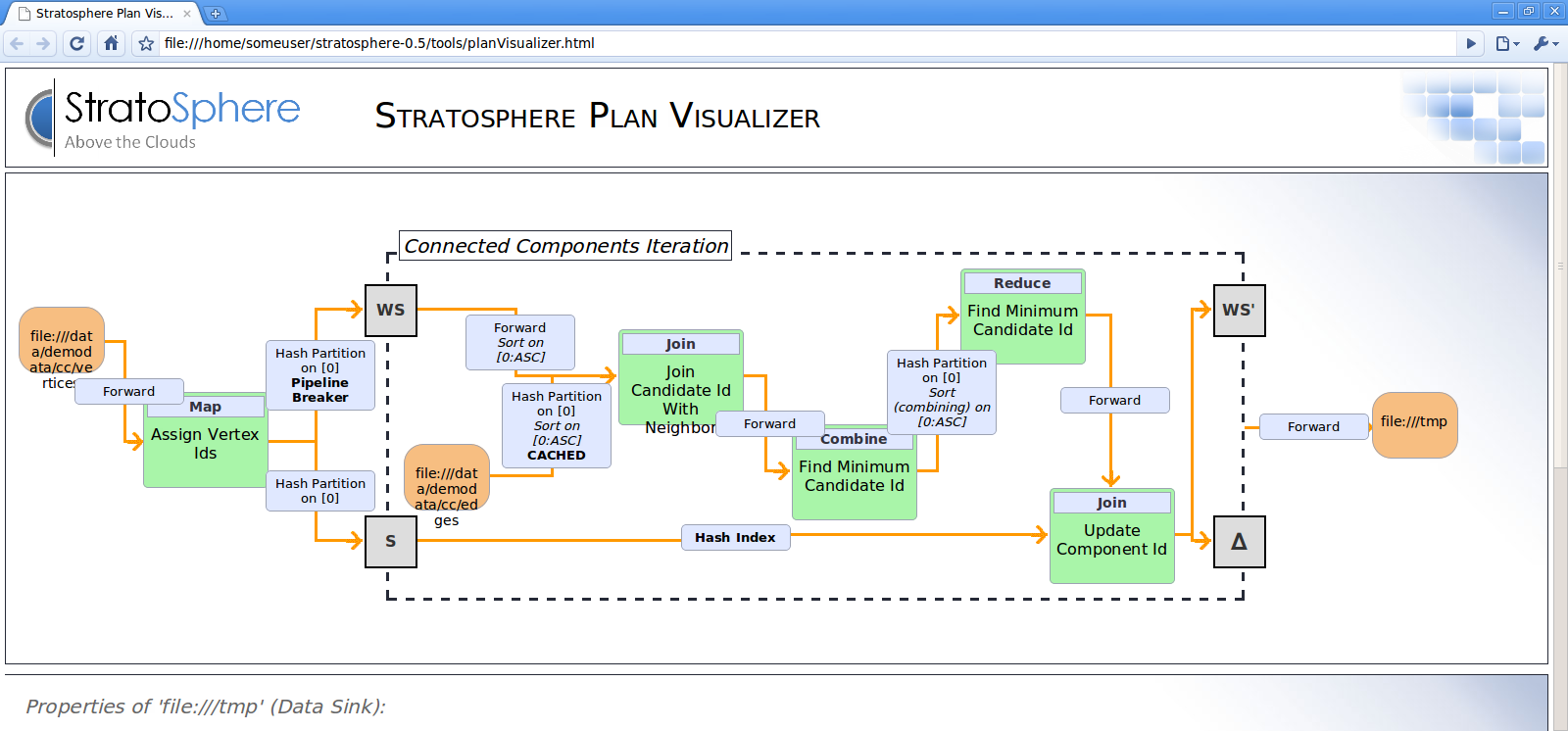

Plan Visualization Tool

Flink 0.5 comes packaged with a visualization tool for execution plans. The HTML document containing the visualizer is located under tools/planVisualizer.html. It takes a JSON representation of the job execution plan and visualizes it as a graph with complete annotations of execution strategies.

The following code shows how to print the execution plan JSON from your program:

final ExecutionEnvironment env = ExecutionEnvironment.getExecutionEnvironment();

...

System.out.println(env.getExecutionPlan());

To visualize the execution plan, do the following:

- Open

planVisualizer.htmlwith your web browser, - Paste the JSON string into the text field, and

- Press the draw button.

After these steps, a detailed execution plan will be visualized.

Web Interface

Flink offers a web interface for submitting and executing jobs. If you choose to use this interface to submit your packaged program, you have the option to also see the plan visualization.

The script to start the webinterface is located under bin/start-webclient.sh. After starting the webclient (per default on port 8080), your program can be uploaded and will be added to the list of available programs on the left side of the interface.

You are able to specify program arguments in the textbox at the bottom of the page. Checking the plan visualization checkbox shows the execution plan before executing the actual program.