This stand-alone repository illustrates the basics of both the sphere tracing method of ray marching and constructive solid geometry modelling with signed distance fields.

The renderer is written specifically to run exclusively on the CPU instead of the GPU so as to best illustrate the entire rendering pipeline as clearly and concisely as possible.

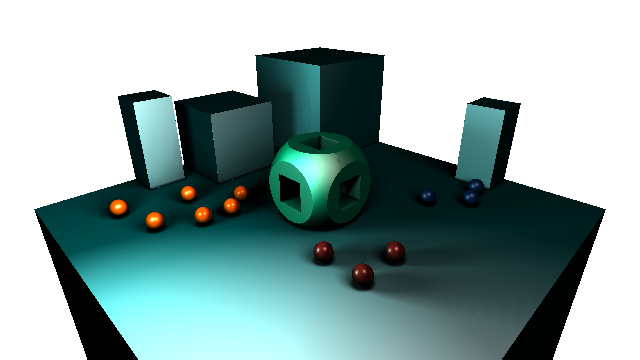

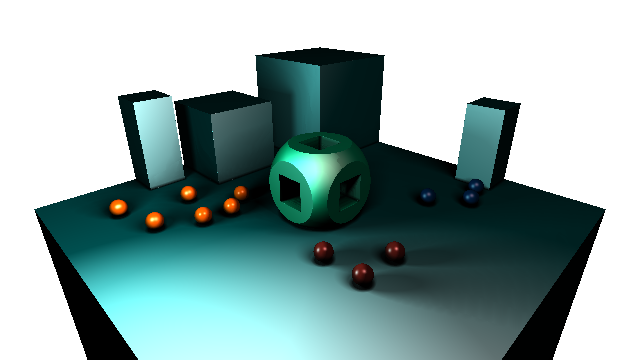

When run, the program produces this image (writing it to disk in PNG format):

To quickly run this program, install sbt (the interactive Scala build tool), clone this repository and then from the root of the repository run:

sbt run

The project is built from scratch without any external dependencies; the program itself is less than six hundred lines of functional Scala in its entirety.

$ cloc --include-lang=Scala .

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Language files blank comment code

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Scala 1 96 97 565

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The process of generating the image above is based on the combination of the following concepts:

Constructive solid geometry is the technique of using boolean operators to combine geometrical objects. A practicle way to represent CSG objects is with a binary tree, where leaves represent primitives and nodes represent operations.

| CSG storage structure |

|---|

|

The following code snippet shows how CSG is implemented within this demo:

object CSG {

trait Op; object Op { object Union extends Op; object Intersection extends Op; object Difference extends Op }

type Tree = Either[Tree.Node, Tree.Leaf]

object Tree {

case class Node (operation: Op, left: Tree, right: Tree)

case class Leaf (sdf: SDF, material: Material.ID)

def apply (operation: Op, left: Tree, right: Tree): Tree = Left (Node (operation, left, right))

def apply (sdf: SDF): Tree = Right (Leaf (sdf, 0))

def apply (sdf: SDF, material: Material.ID): Tree = Right (Leaf (sdf, material))

}

}

Constructive solid geometry is a powerful abstraction that provides a language with which complex geometry can be defined using relatively simple building blocks.

Given a position in 3D space, a signed distance field, as a construct, can be used to query both the distance of that point to the nearest surface and whether that point is inside or outside of the surface; the resultant value of a signed distance field query is a signed real number, the magnitude of which indicates the distance between the point and the surface, the sign indicates whether the point lies inside (negative) or outside (positive) the surface.

Signed distance fields are often used in modern game engines where a discrete sampling of points in 3D space (which may or may not be updated at runtime) is packed into a 3D texture and then used as a quantised signed distance field lookup to facilitate the implementation of fast realtime shadows.

Another mechanism for constructing a queryable signed distance field is with pure algebra. Take for example a unit sphere, consider the values that signed distance field should return for the following input points:

(0.0, 0.75, 0.0)- inside the unit sphere:-0.25(0.0, 1.25, 0.0)- outside the unit sphere:0.25(1.0, 1.0, 1.0)- on the surface of unit sphere:0.0(0.4, 0.0, 0.3)- inside the unit sphere:-0.5

In this case the result is directly related to the length of the point from the origin.

This can be written algebraically in the form: f (p): SQRT (p.x*p.x + p.y*p.y + p.z*p.z) - 1.0.

More complex and flexible shapes can be defined with more complex equations.

For example the equation given above can be generised to work with spheres of any radius: f (p): SQRT (p.x*p.x + p.y*p.y + p.z*p.z) - RADIUS.

The follow code snippet shows this demo's alegbraic implementations:

// Signed distance function for a unit sphere (radius = 1).

def sphere (offset: Vector, radius: Double)(position: Vector): Double = (position - offset).length - radius

// Signed distance function for a unit cube (h, w, d = 1).

def cube (offset: Vector, size: Double)(position: Vector): Double = {

val d: Vector = (position - offset).abs - (Vector (size, size, size) / 2.0)

val insideDistance: Double = Math.min (Math.max (d.x, Math.max (d.y, d.z)), 0.0)

val outsideDistance: Double = d.max (0.0).length

insideDistance + outsideDistance

}

def cuboid (offset: Vector, size: Vector)(position: Vector): Double = {

val q: Vector = (position - offset).abs - (size / 2.0)

q.max (0.0).length + Math.min (Math.max (q.x, Math.max (q.y, q.z)), 0.0)

}

Algebraic signed distance functions work well with constructive solid geometry techniques as the boolean operators involved can be mapped directly to mathematical operators:

type SDF = Vector => Double

def evaluate (scene: CSG.Tree): SDF = {

def r (t: CSG.Tree): SDF = t match {

case Right (leaf) => leaf.value

case Left (node) => (pos: Vector) => {

val a = pos |> r (node.left)

val b = pos |> r (node.right)

node.value match {

case Op.Intersection => Math.max (a, b)

case Op.Union => Math.min (a, b)

case Op.Difference => Math.max (a, -b)

}

}

}

r (scene)

}

... ... ...

... ... ...

The final render is a composition of multiple datasets produced from the application of the following rendering techniques:

Given a single signed distance function reperesenting a scene, the depth buffer, by defintion, is the natural rasterized representation of that signed distance field at a given camera location:

| Depth buffer | Processing cost |

|---|---|

|

|

This buffer can be easily produced by sphere tracing the Scene SDF with a ray corresponding to each camera pixel.

Signed distance functions do not directly provide a way to access surface normals, however, surface normals can be easily estimated by making additional queries of the scene SDF around the axes at given point on a surface.

type SDF = Vector => Double

val NORM_SAMPLE = 0.001

def estimateNormal (pos: Vector, sdf: SDF) = Vector (

sdf (Vector (pos.x + NORM_SAMPLE, pos.y, pos.z)) - sdf (Vector (pos.x - NORM_SAMPLE, pos.y, pos.z)),

sdf (Vector (pos.x, pos.y + NORM_SAMPLE, pos.z)) - sdf (Vector (pos.x, pos.y - NORM_SAMPLE, pos.z)),

sdf (Vector (pos.x, pos.y, pos.z + NORM_SAMPLE)) - sdf (Vector (pos.x, pos.y, pos.z - NORM_SAMPLE))).normalise

| Normals buffer |

|---|

|

This technique introduces, for each pixel representing a surface, a performance hit of six additional queries of the Scene SDF.

In this demo the signed distance function used to represent the scene is composed of multiple signed distance functions using constructive solid geometry. By augmenting the signature of a standard signed distance function it is possible to introduce per object material identification data, which can be used to produce buffers like this Albedo buffer:

| Albedo buffer |

|---|

|

Augmenting the signature of the SDF such that, in addition to returning a depth value, a material identifier associated with the object at the given location is also returned can be used in conjuction with an augumented version of the function above to support CSG composition of objects with material associations. The following snippet shows how the CSG evaluation function can be adjusted:

type MaterialSDF = Vector => (Double, Material.ID)

def evaluate (scene: CSG.Tree): MaterialSDF = {

def r (t: CSG.Tree): MaterialSDF = t match {

case Right (leaf) => (v: Vector) => (v |> leaf.sdf, leaf.material)

case Left (node) => (pos: Vector) => {

val a = pos |> r (node.left)

val b = pos |> r (node.right)

node.operation match {

case Op.Union => (a, b) match {

case ((a, am), (b, _)) if a <= b => (a, am)

case (_, (b, bm)) => (b, bm)

}

case Op.Intersection => (a, b) match {

case ((a, am), (b, _)) if a >= b => (a, am)

case ((_, am), (b, _)) => (b, am)

}

case Op.Difference => (a, b) match {

case ((a, am), (b, _)) if a >= -b => (a, am)

case ((_, am), (b, _)) => (-b, am)

}

}

}

}

r (scene)

}

This technique makes it easy to assign material idenfiers to simple SDF shapes and then compose them in the conventional manner using CSG.

... ... ...

| Hard Shadows | Processing cost |

|---|---|

|

|

... ... ...

| Soft Shadows |

|---|

|

... ... ...

| Ambient Occlusion |

|---|

|

The lighting technique used in the demo is simply an application of the Phong lighting model. The input data required to apply the Phong lighting model is limited to surface positions, surface normals, material properties and camera location; all required input data is easily derived from calculations used and descibed already in this article, as such, when it comes to this particular lighting technique, there is no relevance or change in approach needed due to the demo scene being defined as a SDF.

| Ambient component | Diffuse component | Specular component |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

The final image is a composition, using varied blending techniques, of the data buffers produced during the execution of the demo and illustrated above in this article.

| Aggregate composition |

|---|

|

- Ignation Quilezles' Homepage

- Jamie Wong, Ray marching signed distance functions

- Alex Benton, Ray marching and signed distance fields

- 9-bit Science, Raymarching distance fields

- Wikipedia, Signed Distance Function

This software is licensed under the MIT License; you may not use this software except in compliance with the License.

Unless required by applicable law or agreed to in writing, software

distributed under the License is distributed on an "AS IS" BASIS,

WITHOUT WARRANTIES OR CONDITIONS OF ANY KIND, either express or implied.

See the License for the specific language governing permissions and

limitations under the License.