My personal notes on the book Clean Architecture: A Craftsman's Guide to Software Structure and Design by Robert C. Martin

- What is Design and Architecture

- A Tale of Two Values

- Paradigm Overview

- Structured Programming

- Object Orient Programming

- Functional programming

- Design Principles of SOLID: SRP

- Design Principles of SOLID: OCP

- Design Principles of SOLID: LSP

- Design Principles of SOLID: ISP

- Design Principles of SOLID: DIP

- Components

- Component Principles: Cohesion

- Component Principles: Coupling

- Architecture

- Independence

- Boundaries: Drawing Lines

- Boundary Anatomy

- Policy and Level

- Business Rules

- The Clean Architecture

- Services: Great and Small

- Test Boundaries

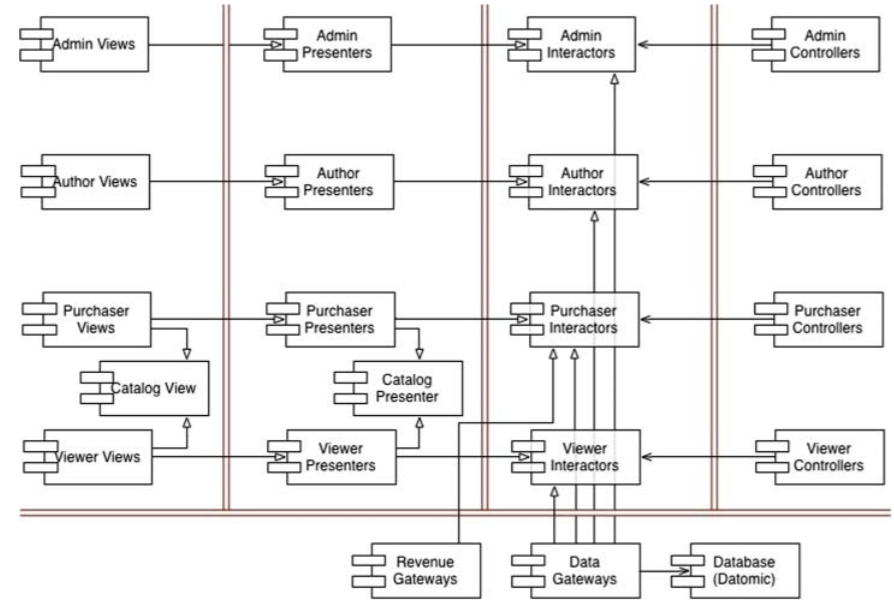

- Case Study: Video Sales

- There is no difference between design and architecture

- 'Architecture' is used in high-level context, whereas 'design' is used in low-level context. But both are part of the whole software design

- The goal of software architecture is to minimize the human resources required to build and maintain the required system

- The best option is for the development organization to recognize and avoid its own overconfidence and to start taking the quality of its software architecture seriously

- Every software system provides two different values to the stakeholders: behavior and structure

- Software developers are responsible for ensuring that both those values remain high

- Function or architecture? Which of these two provides the greater value?

- The first value of software —behavior— is urgent but not always particularly important

- The second value of software —architecture— is important but never particularly urgent

- Software priorities lie within these 4 points:

-

- Urgent and important

-

- Not urgent and important

-

- Urgent and not important

-

- Not urgent and not important

-

- A paradigm tells you which programming structures to use, and when to use them.

- There are three paradigms: structured programming - object orient programming - functional programming

- Structured programming: imposes discipline on direct transfer of control (ex: if/else/then)

- Object orient programming: imposes discipline on indirect transfer of control (ex: polymorphism/function pointers)

- Functional programming: imposes discipline upon assignment (ex: mathematical symobls)

- Via structured programming, programmers could break down large proposed systems into modules and components that could be further broken down into tiny provable functions

- OOP supports the proper admixture of: encapsulation, inheritance, and polymorphism

- Encapsulation allows data to be hidden and only functions are known. We see this concept in action as the private data members and the public member functions of a class

- Variables in functional languages do not vary/are not modified

- It is important to consider immutable variables because: All race conditions, deadlock conditions, and concurrent update problems are due to mutable variables.

- You cannot have a race condition or a concurrent update problem if no variable is ever updated. You cannot have deadlocks without mutable locks

- As an architect, you must be asking yourself whether immutability is practicable

- One of the most common compromises in regard to immutability is to segregate the application into: mutable and immutable components

- Immutable components perform their tasks in a functional way, without using any mutable variables

- Imagine if we added up all the transactions of a bank client, we'd require a lot of processing power

- But we could use event sourcing and have enough storage to perform that

- the event sourcing stategy here is we store the transactions, but not the state. When state is required, we simply apply all the transactions from the beginning of time

- We could therefore not update or delete anything, and thus making our application immutable, therefore functional

- Event Sourcing ensures that all changes to application state are stored as a sequence of events

-

The SOLID principles tell us how to arrange our functions and data structures into classes, and how those classes should be interconnected

-

The goal of SOLID for software is to:

-

- tolerate changes

-

- easy to understand

-

- make components used in many software

-

-

Each principle of SOLID is as follows:

- 1. SRP: The Single Responsibility Principle

- The best structure for a software is influenced by the social structure of the organization that uses it so that each software module has one, and only one, reason to change

- 2. OCP: The Open-Closed Principle

- The gist is that for software to be easy to change, it must be designed to allow the behavior of it to be changed by adding new code, rather than changing existing code

- 3. LSP: The Liskov Substitution Principle

- To build software from interchangeable parts, those parts must adhere to a contract that allows those parts to be substituted one for another

- 4. ISP: The Interface Segregation Principle

- Avoid depending on things that you don’t use

- 5. DIP: The Dependency Inversion Principle

- The code that implements high-level policy should not depend on code that implements low-level details. Rather, details should depend on policies

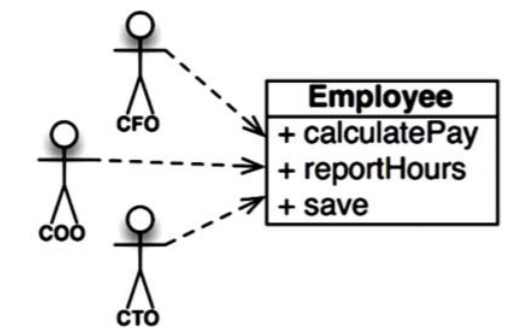

- 1. SRP: The Single Responsibility Principle

- It is wrong to assume that SRP means that every module should do just one thing. There is a principle like that, a function should do one thing

- Software systems are changed to satisfy users and stakeholders; those users and stakeholders are the “reason to change” that the principle is talking about

- But since users/skateholders change, we'll refer to them as actors

- Thus, the definition of The Single Responsibility Principle (SRP) is:

- A module should be responsible to one, and only one, actor

- What we mean by a module is just basically a source file or set of functions

- An

Employeeclass that has three functions,calculatePay(), reportHours(), and save()would violate SRP because:- Those three methods are responsible to three different actors

- The

calculatePay()method would be specified by the accountant, who reports to the CFO - The

reportHours()method would be specified by HR, who reports to the COO - The

save()method would be specified by the DBA, who reports to the CTO

- The

- Those three methods are responsible to three different actors

- When a new function like

regularHours()is added and is used incalculatePay(), developers may not pay attention if the method is also used inregularHours()which could result in not testing it in the two methods and cause issues after deployment - The key here in this example is that the SRP says to separate the code that different actors depend on

- Multiple people changing the same source file for different reasons causes risks

- One solution is to seperate code that supports different actors

-

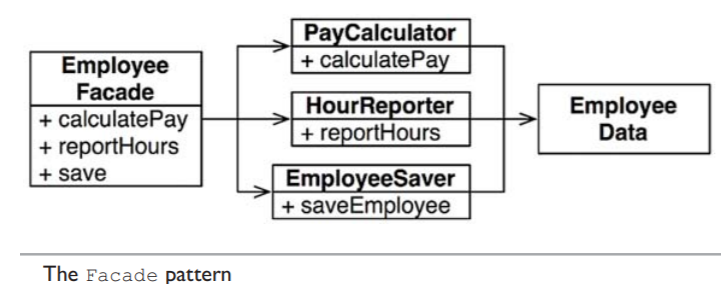

One way to solve the above

Employeeclass is to seperate data from functions

-

However, the downside of this is developers now have 3 classes they have to instantiate and track. A common solution here is to use the Facade pattern

-

The

EmployeeFacadecontains very little code, so the solution is to keep the most important method in the originalEmployeeclass and then using that class as a Facade for the lesser functions, like above

- The definition of OCP is: A software artifact should be open for extension but closed for modification

- In other words, the behavior of a software artifact ought to be extendible, without having to modify that artifact

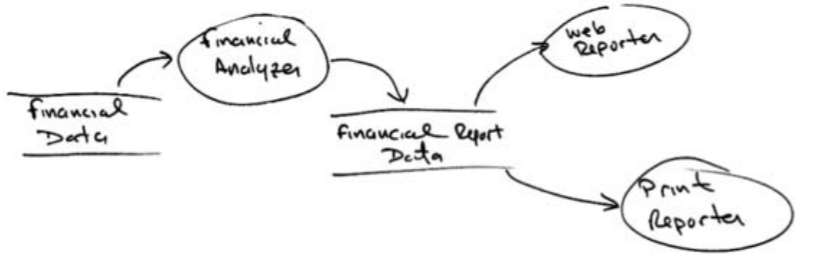

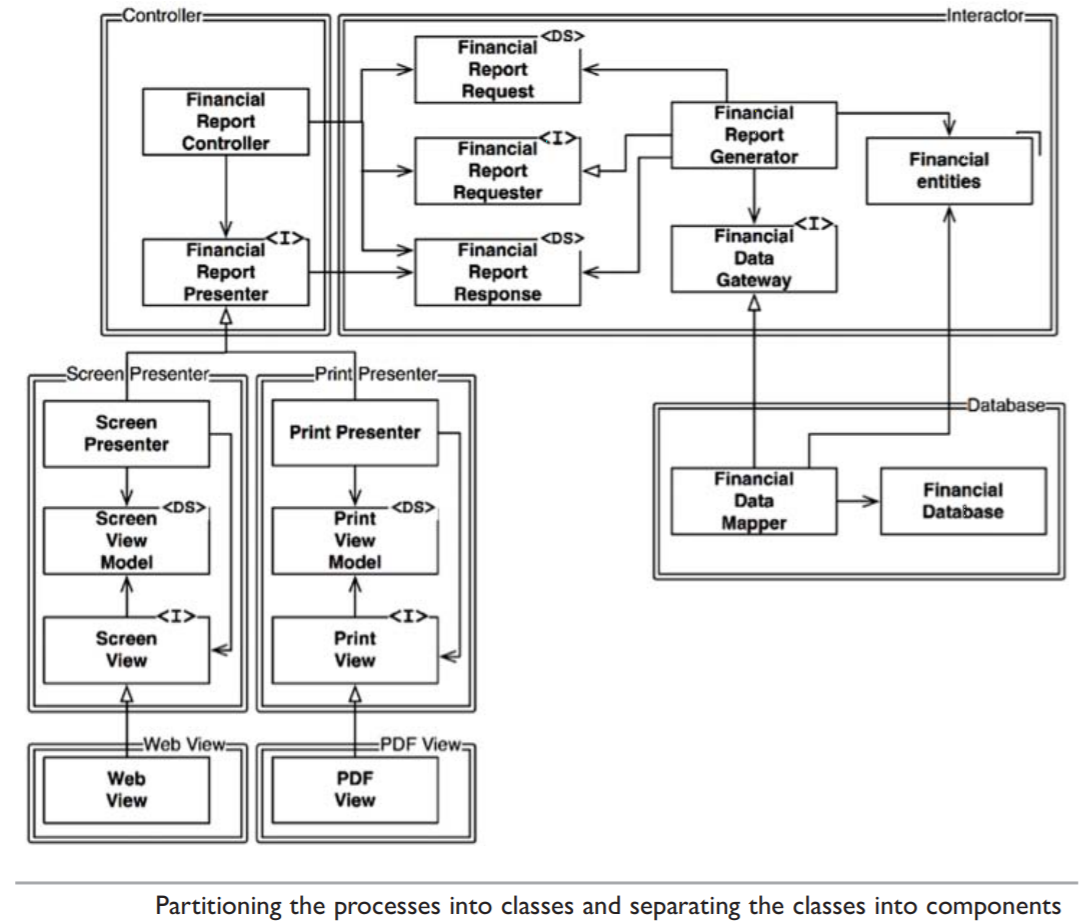

- We have a webapp that displays summary of financial info that is scrollable and display negative numbers in red color

- A request was made to print a repot in only black and white

- A good software architecture here would reduce the amount of changed code via:

- Separating the things that change for different reasons (SRP) and then organizing the dependencies between those things properly (DIP)

- Following SRP would result in a plan like this:

- The essential insight here is that generating the report involves 2 separate responsibilities:

- The calculation of the reported data

- The presentation of the data

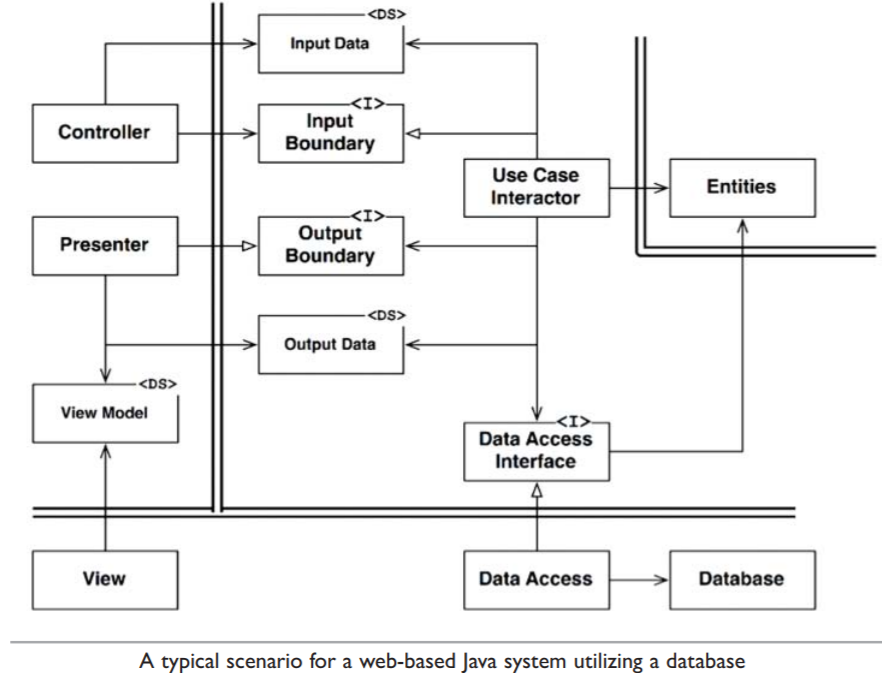

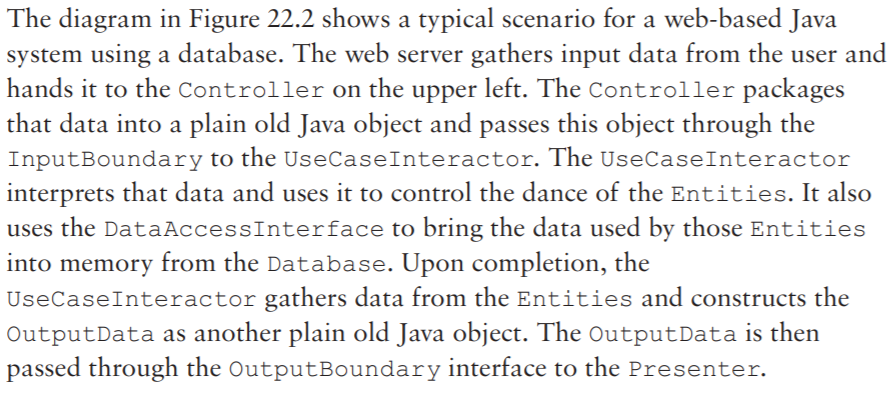

- This sepeation can be done, like above, by having a: Controller - Interactor - Database - Presenter - Views

- Open arrowheads are using relationships. Closed arrowheads are implements or inheritance relationships

- Notice that each double line is crossed in one direction only. This means that all component relationships are unidirectional

FinancialDataMapperknows aboutFinancialDataGatewaythrough an implements relationship, butFinancialGatewayknows nothing at all aboutFinancialDataMapper

- We can see that we have arrows that point toward the components that we want to protect from change

- If component A should be protected from changes in component B, then component B should depend on component A

- We want to protect the Controller from changes in the Presenters

- We want to protect the Presenters from changes in the Views

- We want to protect the Interactor from changes in—well, anything

- Changes to the Database, or the Controller, or the Presenters, or the Views, will have no impact on the Interactor

- Why should we protect the Interactor? Because it contains the business rules, and the highest-level policies

- Notice how there's levels of protection:

- Interactor has the highest level, Controller is next, then the Presenter, and last is the Views

- This is how the OCP works: it separates functionality based on how, why, and when it changes, and then organize them into protection levels

- The

FinancialReportRequesterinterface purpose is to protect theFinancialReportControllerfrom knowing too much about theInteractor - If the interface were not there, the Controller would have transitive dependencies on the

FinancialEntities - Our first priority is to protect the Interactor from changes to the Controller, but we also want to protect the Controller from changes to the Interactor by hiding the internals of the Interactor

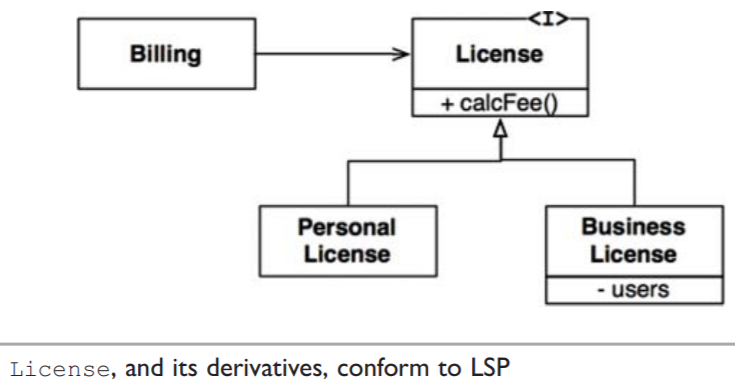

- Definition: What is wanted here is something like the following substitution property: If for each object o1 of type S there is an object o2 of type T such that for all programs P defined in terms of T, the behavior of P is unchanged when o1 is substituted for o2 then S is a subtype of T

- This design conforms to LSP because: the behavior of the

Billingdoes not depend on any of the 2 subtypes Both of the subtypes are substitutable for theLicenseclass

- Above,

Squareis not a proper subtype ofRectanglebecause the height and width of the Rectangle are independently mutable - In contrast, the height and width of the

Squaremust change together - Since the User believes it is communicating with a

Rectangle, it could easily get confused

- To adjust to LSP principle in this example, we add mechanisms to the User (such as an if statement) that detects whether the

Rectangleis a Square - Since the behavior of the User depends on the types it uses, those types are not substitutable

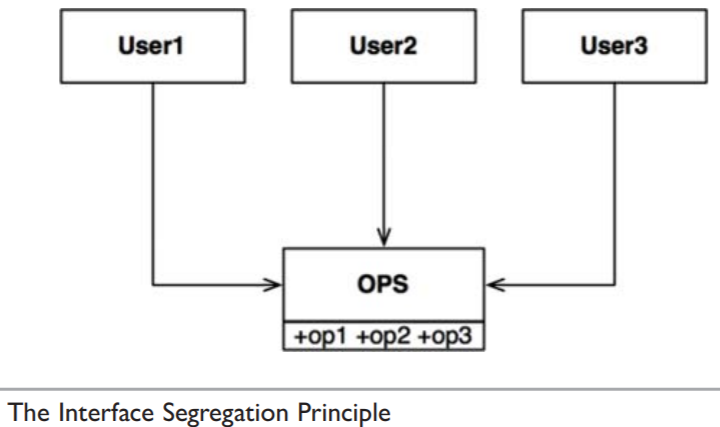

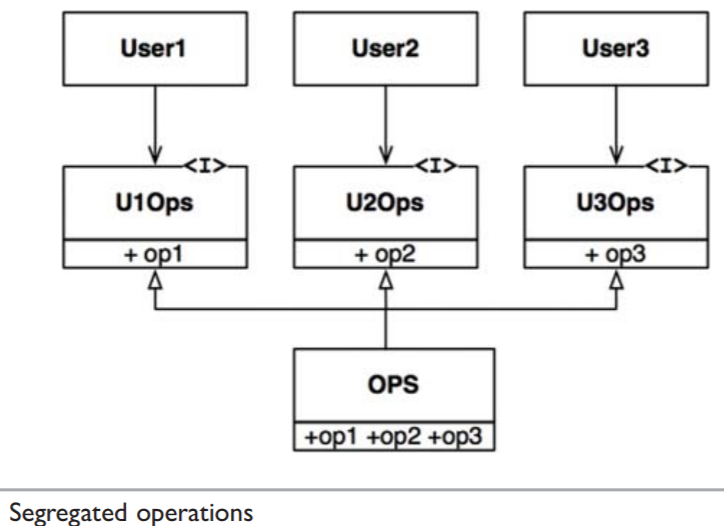

- Definition: Clients should not be forced to depend upon interfaces that they do not use

- Imagine if User1 uses only op1, and User2 uses only op2, and User3 uses only op3

- When we run a program with this class, User1 will still depend on op2 and op3 even though it doesn't call them

- Any change to op2 and op3 will force User1 to be recompiled

- The fix here is to segregate the operations into interfaces as shown below

- ISP is a language issue, rather than an architecture issue. This is because the above program would not run into issues at run time in a dynamically type language like Python

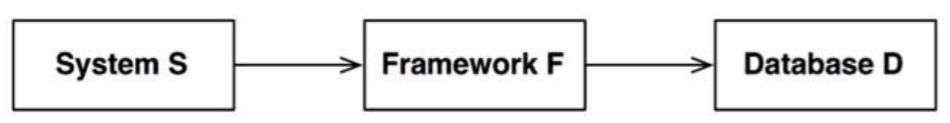

- We see that S depends on F, and F depends on D. Any changes in D will force redeployment in S and F, which can cause issues

- DIP tells us that the most flexible systems are those in which source code dependencies refer only to abstractions, not to concretions

- In other words, 'import', 'use', and 'include' should refer to interfaces and abstract classes only, not concrete classes

- Rules of DIP:

- Don't refer to volatile concrete classes: refer to Abstract/interfaces instead

- Don’t derive from volatile concrete classes

- Don’t override concrete functions

- Never mention the name of anything concrete and volatile

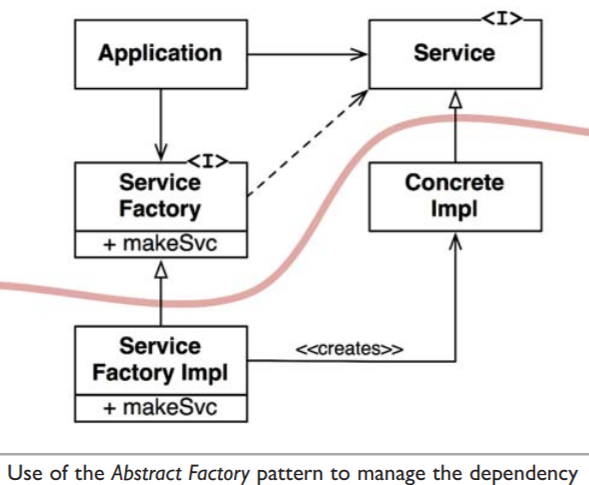

- The

Applicationuses theConcreteImplthrough theServiceinterface - However, the

Applicationmust somehow create instances of theConcreteImpl - To achieve this, without creating a source code dependency on the

ConcreteImpl, theApplicationcalls themakeSvcmethod of theServiceFactoryinterface - This method is implemented by the

ServiceFactoryImplclass, which derives fromServiceFactory - That implementation instantiates the

ConcreteImpland returns it as aService - The curved line is an architectural boundary. It separates the abstract from the concrete

- The curved line divides the system into 2 components: abstract - concrete

- The abstract component contains all the high-level business rules of the application. The concrete component contains all the implementation details that those business rules manipulate

- Note the flow of control crosses the curved line in the opposite direction of the source code dependencies

- The source code dependencies are inverted against the flow of control—which is why we refer to this principle as Dependency Inversion

- If the SOLID principles tell us how to arrange the bricks into walls and rooms, then the component principles tell us how to arrange the rooms into buildings

- Large software systems, like large buildings, are built out of smaller component

- Components are the units of deployment. They are the smallest entities that can be deployed as part of a system. In Java, they are jar files

- Components can be linked together into a single executable. Or they can be aggregated together into a single archive, such as a .war file. Or they can be independently deployed as separate dynamically loaded plugins, such as.jar or .dll or .exe files

- The three principles of component cohesion:

- REP: The Reuse/Release Equivalence Principle

- CCP: The Common Closure Principle

- CRP: The Common Reuse Principle

- Definition: The granule of reuse is the granule of release

- Only components that are released through a tracking system can be effectively reused

- It's common for developers to be alerted about a new release and decide, based on the changes made in that release, to continue to use the old release or not

- Classes and modules that are grouped together into a component should be releasable together

- Definition: Gather into components those classes that change for the same reasons and at the same times. Separate into different components those classes that change at different times and for different reasons

- This is the SRP restated for components. Just as the SRP says that a class should not contain multiples reasons to change, so the CCP says that a component should not have multiple reasons to change

- Definition: Don’t force users of a component to depend on things they don’t need

- When one component uses another, a dependency is created between the components

- Because of that dependency, every time the used component is changed, the using component will likely need corresponding changes

- All in all, Don’t depend on things you don’t need

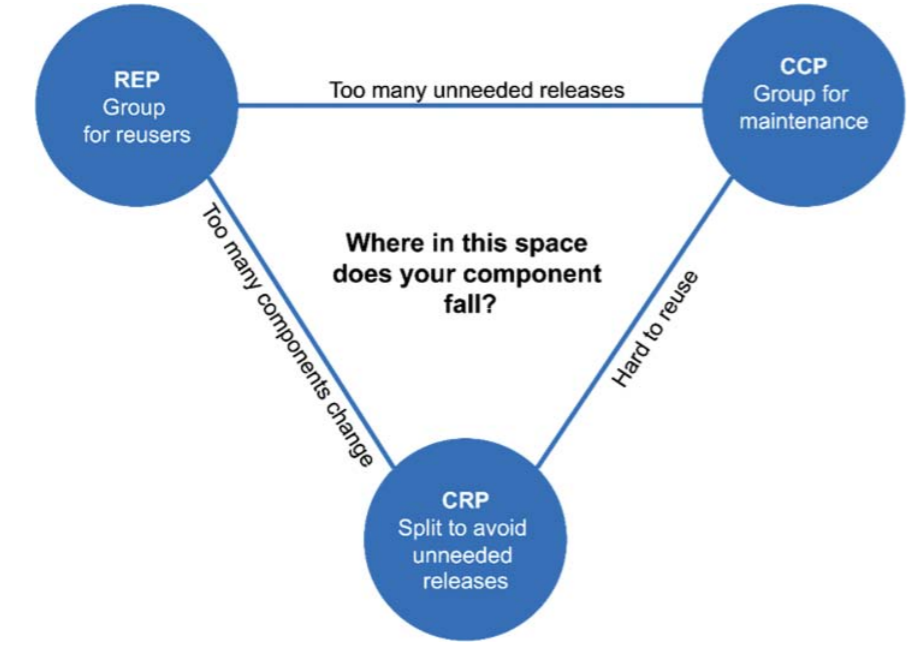

- The REP and CCP are inclusive principles: Both tend to make components larger

- The CRP is an exclusive principle, driving components to be smaller

- It is the tension between these principles that good architects seek to resolve

- The edges of the diagram above describe the cost of abandoning the principle

- An architect who focuses on just the REP and CRP will find that too many components are impacted when simple changes are made

- In contrast, an architect who focuses too strongly on the CCP and REP will cause too many unneeded releases to be generated

- A good architect finds a position in that tension triangle that meets the current concerns of the development team, but is also aware that those concerns will change over time

- For example, early in the development of a project, the CCP is much more important than the REP, because developability is more important than reuse

- The “morning after syndrome” occurs in when developers are modifying the same source files

- Two solutions to this problem are: The weekly build - The Acyclic Dependencies Principle (ADP)

- Definition: Allow no cycles in the component dependency graph

- How it works:

- All developers ignore each other for the first four days of the week

- They all work on private copies of the code, and don’t worry about integrating their work on a collective basis

- Then, on Friday, they integrate all their changes and build the system

- This solution raises another problem, which is that makes integration challenging and may produce more time spent on a project.

- To solve this, partition the development environment into releasable components as the below point

- The components become units of work that can be the responsibility of a single developer/developers

- However, you must manage the dependency structure of the components. There can be no cycles

- The primary purpose of architecture is to support the life cycle of the system

- Good architecture makes the system easy to understand, easy to develop, easy to maintain, and easy to deploy

- The ultimate goal is to minimize the lifetime cost of the system and to maximize programmer productivity

- Software architect provides the best development, deployment, operation, and maintainance

- Software systems need to allow for open option to aid in flexibility

- It is not necessary to choose the following early in the development process because the high-level policy should not care/know:

- Database system

- web server

- REST

- dependency framework.... etc

- Decoupling modes can exist in 3 level: Source level - Deployment level - Service level

- Which kinds of decisions are premature? Decisions that have nothing to do with the business requirements—the use cases—of the system

- These include decisions about frameworks, databases, web servers, utility libraries, dependency injection, and the like

- A good system architecture allows those decisions to be made at the latest possible moment, without significant impact

- It is important to postpone what tool to use for development until later on.

- For example, instead of straight away using MySQL, consider data access methods into an interface and provide functionality for those methodsto find and fetch data

- This example shows how you draw boundaries between business rules and databases

- The database is a tool that the business rules can use indirectly. The business rules don’t need to know about the schema, or the query language, or any of the other details

- It is wrong to define a system in terms of the GUI, and believe that you should see the GUI start working immediately about the database

- Consider a video game, for example. Your experience is dominated by the interface: the screen, the mouse, the buttons, and the sound

- Behind the interface, there is a model—a sophisticated set of data structures and functions driving it

- The interface should not matter to the model or the business rules

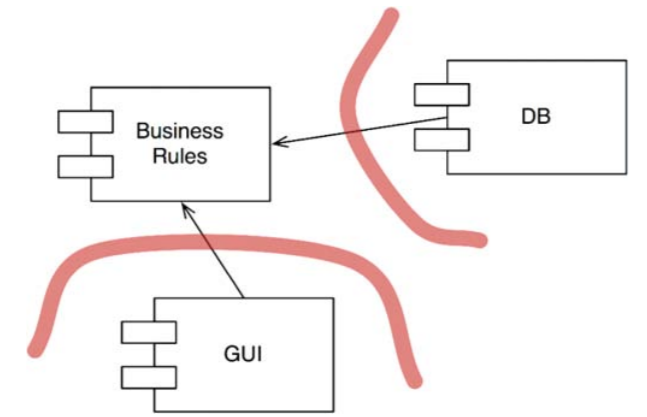

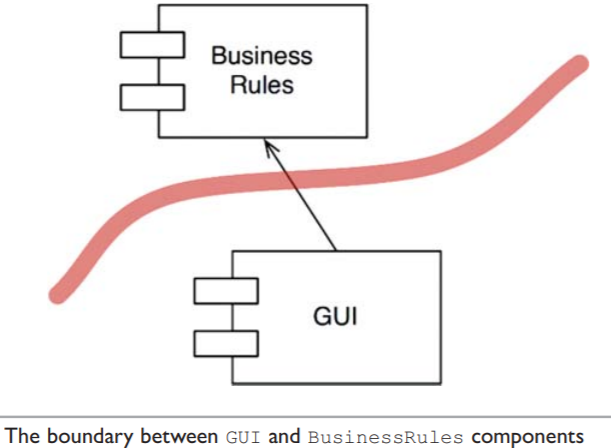

- The

GUIcould be replaced with any other kind of interface, and theBusinessRuleswould not care - Architects should think there would be different kinds of user interfaces for their system. They could be web based, client/server based, SOA based, Console based etc

- To draw boundary lines in software, you first partition the system into components. Some of those components are core business rules; others are functions that are not directly related to the core business

- GUIs and DBs change at different times and at different rates than business rules, so there should be a boundary between them

- This is simply the Single Responsibility Principle again. The SRP tells us where to draw our boundaries

- System boundaries come in many form, we'll discuss: boundary crossing - The Dreaded Monolith

- Boundary crossing is nothing more than a function on one side of the boundary calling a function on the other side and passing along some data

- Creating an appropriate boundary crossing is to manage the source code dependencies

- All dependencies cross the boundary from right to left toward the higher-level component

- High-level components remain independent of lower-level details

- “level” is “the distance from the inputs and outputs.”

- The farther a policy is from both the inputs and the outputs of the system, the higher its level

- The policies that manage input and output are the lowest level policies in the system

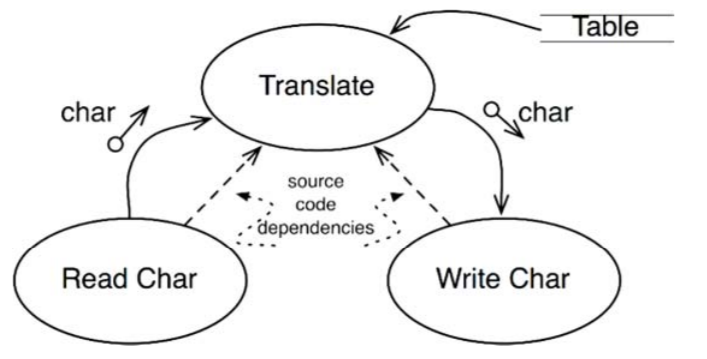

- In the diagram above,

Translateis the highest-level component because it is the farthest from the inputs and outputs - The example below is an incorrect architecture because the high-level

encryptfunction depends on the lower-levelreadCharandwriteCharfunctions

function encrypt() {

while(true)

writeChar(translate(readChar()));

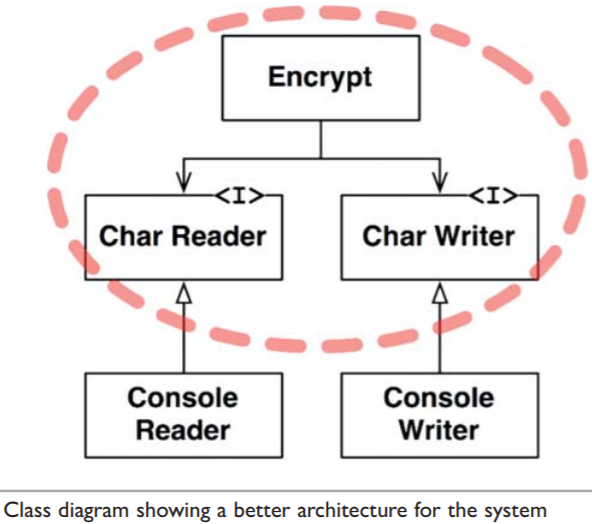

}- A better architecture is shown above, all dependencies point inward

ConsoleReaderandConsoleWriteare low level because they are close to the inputs and outputs- This structure decouples the high-level encryption policy from the lower-level input/output policies

- This makes the encryption policy usable in a wide range of contexts. When changes are made to the input and output policies, they are not likely to affect the encryption policy

- Business rules are rules or procedures that make or save the business money. These rules would make or save the business money

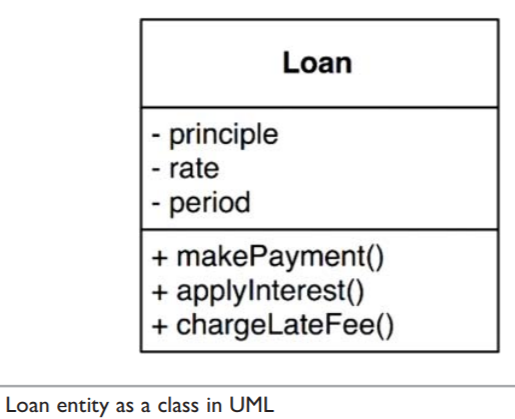

- For example, a bank charges N% interest for a loan is a business rule that makes the bank money

- An Entity is an object within our computer system that embodies a small set of critical business rules operating on Critical Business Data

- This example shows a Loan entity, and it implements a concept that is critical to the business, and is seperated from every other concern (DB, U, framework, etc)

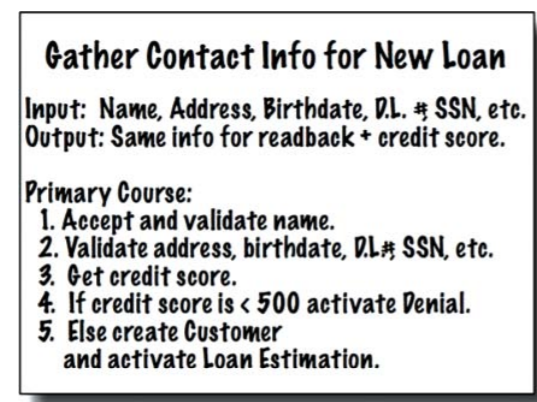

- A use case is a description of the way that an automated system is used. It specifies the input to be provided by the user, the output to be returned to the user, and the processing steps involved in producing that output

- Notice that the use case does not describe the user interface other than to informally specify the data coming in from that interface

- This is very important. Use cases do not describe how the system appears to the user. Instead, they describe the application-specific rules that govern the interaction between the users and the Entities

- Entities are high level and use cases lower level (since use cases are closer to inputs and outputs). Therefore, use cases depend on Entities, not the other way around

- Use case object should have no inkling about the way that data is communicated to the user, or to any other component

- We certainly don’t want the code within the use case to know about HTML or SQL

- The use case accepts simple request data structures for its input, and returns simple response data structures as its output

- These data structures are not dependent on anything. They do not derive from standard framework interfaces such as HttpRequest and HttpResponse. They know nothing of the web, nor do they share any of the trappings of whatever user interface

- This lack of dependencies is critical

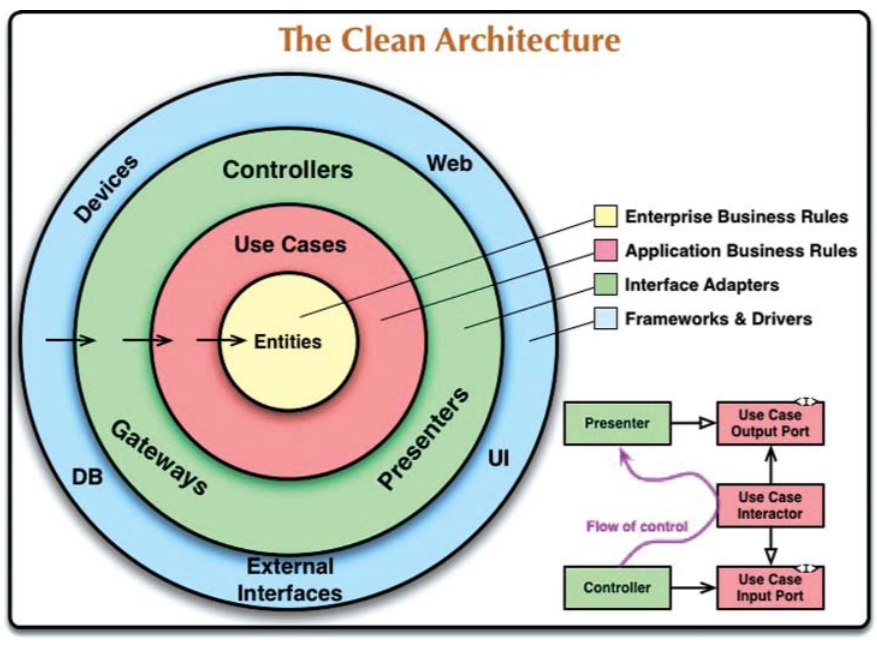

- A good architectures produces systems that have the following characteristics:

- Independent of frameworks: does not depend on libraries or frameworks, which let go of limited constraints

- Testable: The business rules can be tested without the UI, database, web server, or any other external element

- Independent of the UI: The UI can change easily, without changing the rest of the system

- Independent of the database: You can swap out SQL for Mongo, or something else. Your business rules are not bound to the database

- Independent of any external agency: your business rules don’t know anything at all about the interfaces to the outside world

- Nothing in an inner circle can know anything at all about something in an outer circle.

- The name of something declared in an outer circle must not be mentioned by the code in an inner circle. That includes functions, classes, variables, or any other named software entity

- Services, or microservices, appear to support independence of development and deployment. Again, as we shall see, this is only partially true

- Even though they are decoupled, they still share resources/networks or the data they share

- For example, if a new field is added to a data record that is passed between services, then every service that operates on the new field must be changed

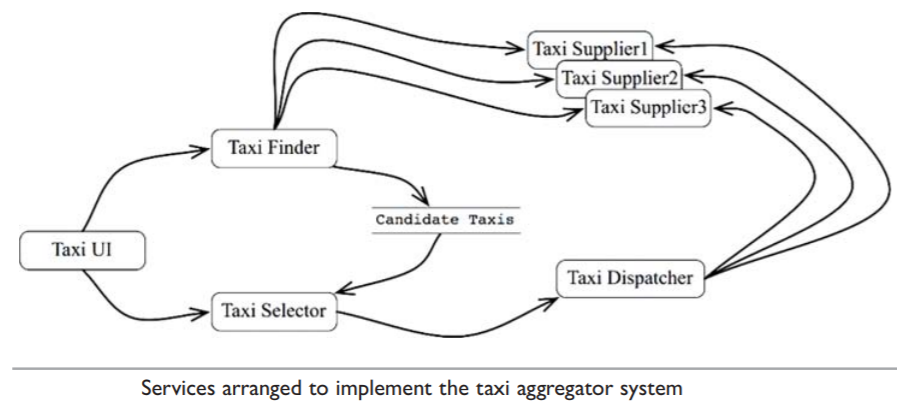

- Imagine we have a taxi aggregator system, and developers announced a new feature, kitten delivery service to the city. Users can order kittens to be delivered to their homes or to their places of business

- Of course, some drivers and customers will be allergic and can't use the new service

- Looking at the diagram, all of the services will need to be changed to add the new feature because the services are coupled and cannot be independently developed

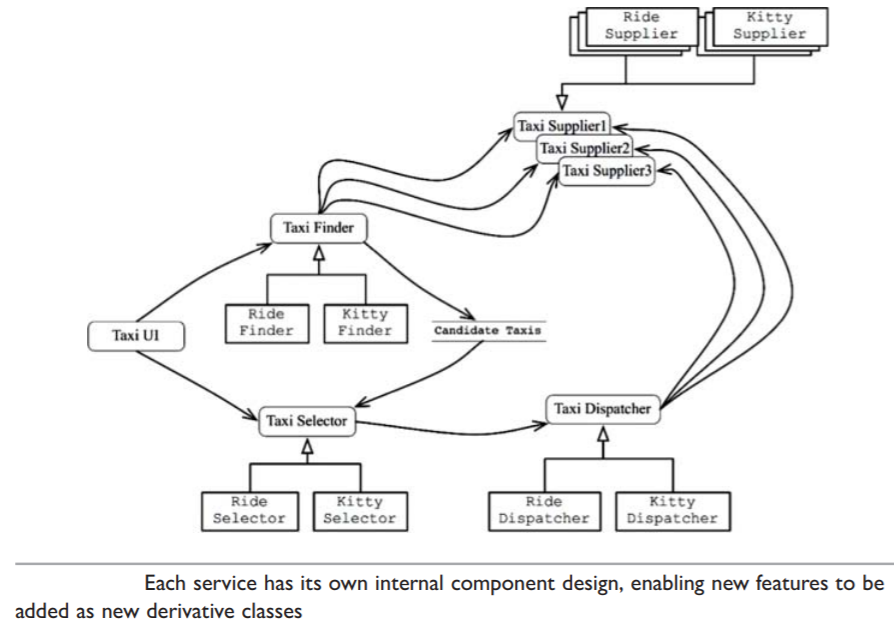

- To solve the above example when adding the new feature, we carefully follow SOLID principles and create a set of classes that could be polymorphically extended to handle new features. Much of the logic is preserved within the base classes via components

- The

RideandKittenscomponents now ovveride the abstract base classes using the Template Method and Strategy patterns

- The 2 components also follow the dependency rule, and the classes that implement those features are created by factories under the control of the UI

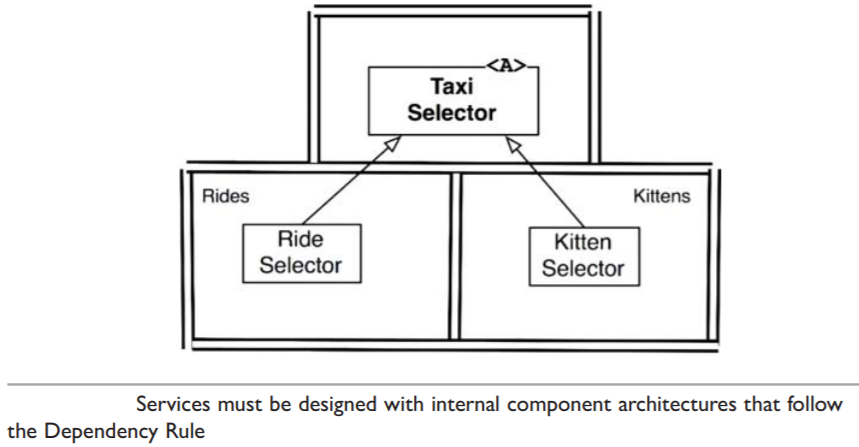

- Services must be designed with internal component architectures that follow the Dependency Rule, like shown above

- Those services do not define the architectural boundaries of the system; instead, the components within the services do

- Test need not to be isolated from system designs. Test that break when designs change are called 'Fragile Test problems'

- Use APIs to decouple the structure of the tests from the structure of the application (exs: verify business rules, and detatch tests from UI)

- The role of the testing API is to hide the structure of the application from the tests. This allows the production code to be refactored and evolved in ways that don’t affect the tests

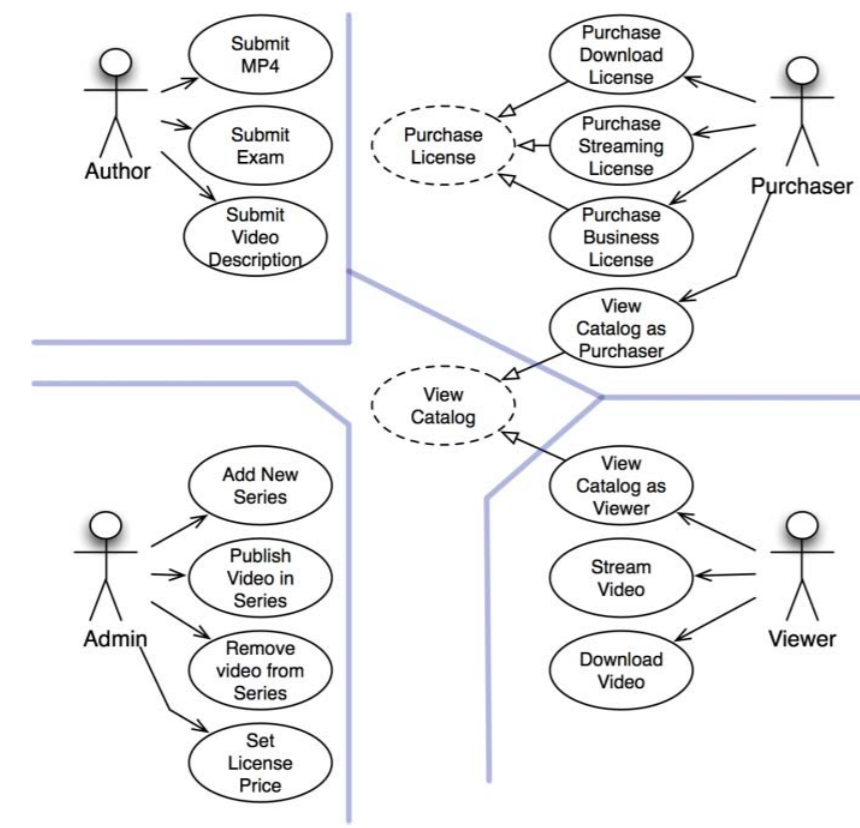

- The case study is a software that sells videos like cleancoders

- The first step to draw the architecture is to identify the actors and use cases

- According to the Single Responsibility Principle, these four actors will be the four primary sources of change for the system

- A change to a feature in one actor will not affect any other actor

- Note the dashed use cases. They are abstract use cases. An abstract use case is one that sets a general policy that another use case will flesh out

- The double lines in the drawing represent architectural boundaries

- Note the partitioning of views, presenters, interactors, and controllers

- Note that each actor has their own categories

- Each component will contain the views, presenters, interactors, and controllers

- Note the special components for the

Catalog Viewand theCatalog Presenter. This is how the abstract View Catalog use case is dealt with

- The flow of control proceeds from right to left

- Input occurs at the controllers, and that input is processed into a result by the interactors

- The presenters then format the results, and the views display those presentations

- Notice the arrows do not all flow from the right to the left. The architecture is following the Dependency Rule

- All dependencies cross the boundary lines in one direction, and they always point toward the components containing the higher-level policy

- Note that the using relationships (open arrows) point with the flow of control, and that the inheritance relationships (closed arrows) point against the flow of control

- This depicts our use of the Open–Closed Principle to make sure that the dependencies flow in the right direction, and that changes to low-level details do not ripple upward to affect high-level policies

.PNG)