This is the manifest of things I've learned about managing CSS in large, complex web projects during my many years of professional web development. I've been asked about these things enough times that having a document to point to sounded like a good idea.

I've tried to keep the explanations short, but this is essentially the tl;dr:

- Always prefer classes

- Co-locate component code

- Use consistent class namespacing

- Maintain a strict mapping between namespaces and filenames

- Prevent leaking styles outside the component

- Prevent leaking styles inside the component

- Respect component boundaries

- Integrate external styles loosely

If you're working with frontend applications, eventually you'll need to style things. And even though the state-of-the-art of frontend applications keeps blazing ahead, CSS is still the only way to style anything on the web (and lately, in some cases, native applications too). There's two broad categories of styling solutions out there, namely:

- CSS preprocessors, which have been around for ages (such as SASS, LESS, and others)

- CSS-in-JS libraries, which are a relatively new approach to styling (such as free-style, and many others)

The choice between the two approaches is a topic for a separate article, and as usual, both have their pros and cons. That said, I'll be focusing on the former approach, and if you've chosen to go with the latter, this article will probably be a bit less interesting.

So we're after a robust, scalable CSS architecture. But what properties does that call for, specifically?

- Component oriented - The best way to deal with UI complexity is to split the UI into smaller components. If you're using a sensible framework, the JavaScript side of this will come naturally. React, for instance, encourages a high-level of componentization and compartmentalization. We want a CSS architecture to match.

- Sandboxed - Splitting the UI into components won't help our cognitive load if touching the styles of one component can have unwanted and unpredictable effects on another. Fundamental CSS features such as the cascade, and a single, global namespace for identifiers actively work against you in this regard. If you're familiar with the Web Components spec, think of this as getting the style isolation benefits of the Shadow DOM without having to care about browser support (or whether or not the spec ever gets serious traction).

- Convenient - We want all the nice things, and we don't want to work for them. That is, we don't want to make our developer experience any worse by adopting this architecture. If possible, we want to make it better.

- Err on the side of safety - Somewhat related to the previous point, we want everything to be local by default, and global only as an exception. We engineers are lazy people, and the path of least resistance always needs to point to the correct solution.

This is just to get the obvious out of the way.

Do not target ID's (e.g. #header), because whenever you think there can be only one instance of something, on an infinite timescale, you'll be proven wrong. One past example of this was when we wanted to weed out any data-binding bugs on a large application we were working on. We started two instances of our UI code, side-by-side in the same DOM, both bound to a shared instance of our data model. This was to make sure that all changes in the data model were correctly reflected in both UI's. Any components that you might have assumed to always be unique, such as a header bar, no longer are. This is a great benchmark for surfacing other subtle bugs related to assumptions about uniqueness too, by the way. I digress, but the moral of the story is: there's no situation where targeting an ID would be a better idea than targeting a class, so let's just not, ever.

Neither should you target elements (e.g. p) directly. It's often OK to target elements that belong to a component (see below), but on their own, eventually you'll end up having to undo those styles for a component that doesn't want them. Recalling our high-level goals, this also goes against just about all of them (component-orientedness, avoiding the cascade like the plague, and being local by default). Setting things like fonts, line-heights and colors (a.k.a inherited properties) on body can be the exception to this rule if you so choose, but if you're serious about component isolation, it's completely feasible to forgo even these (see below about working with external styles).

So with very few exceptions, your styles should always target a class.

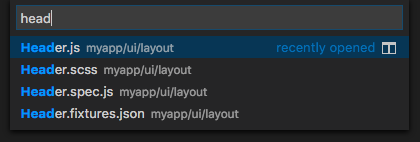

When working on a component, it helps tremendously if everything related to that component — its JavaScript, styles, tests, documentation, etc — live very close to each other:

ui/

├── layout/

| ├── Header.js // component code

| ├── Header.scss // component styles

| ├── Header.spec.js // component-specific unit tests

| └── Header.fixtures.json // any mock data the component tests might need

├── utils/

| ├── Button.md // usage documentation for the component

| ├── Button.js // ...and so on, you get the idea

| └── Button.scss

When you're working in the code, simply open your project browser, and all other aspects of the component are at your fingertips. There's a natural coupling between the styles and the JavaScript that produces your DOM, and it's a fair bet you'll be touching one soon after touching the other. The same applies to a component and its tests, for example. Think of this as the locality of reference principle for UI components. I, too, used to meticulously maintain separate mirrors of my source tree under styles/, tests/, docs/ etc, until I realized that literally the only reason I kept doing that was because that's how I'd always done it.

CSS has a single, flat namespace for class names and other identifiers (such as ID's, animation names, etc). Just like in the PHP days of old, the community has dealt with this by simply using longer, structured names, thus emulating namespaces (BEM is an example). We'll want to choose a namespacing convention, and stick with it.

For instance, let's say we use myapp-Header-link as a class name. Each of its 3 parts have a specific function:

myappto first isolate our app from other apps possibly running on the same DOMHeaderto isolate the component from other components in the applinkto reserve a local name (within the component's namespace) for our local styling purposes

As a special case, the root element of the Header component can be simply marked with the myapp-Header class. For a very simple component, that might be all you need.

Whatever namespacing convention we choose, we'll want to be consistent about it. In addition to each of the 3 parts having a specific function, they'll also have a specific meaning. Just by looking at a class, you'll know where it belongs. The namespacing will be the map by which we navigate the styles of our project.

From now on I'll assume the namespacing scheme of app-Component-class, which I've personally found to work really well, but you can of course also come up with your own.

This is just the logical combination of the preceding two rules (co-locating component code, and class namespacing): all styles affecting a specific component should go to a file named after the component. No exceptions.

If you're working in the browser, and you spot a component that's misbehaving, you can right-click-Inspect it, and you'll see for instance:

<div class="myapp-Header">...</div>Noting the name of the component you switch to your editor, hit the key combo for "Quick open file", start typing "head", and there you go:

This strict mapping from UI components to the corresponding source files is doubly useful if you're new on the team and don't know the architecture by heart yet: you don't need to, to be able to find the guts of the thing you're supposed to work on.

There's a natural (but perhaps not immediately obvious) corollary to this: a single style file should only contain styles belonging to a single namespace. Why? Say we have a login form, that's only used within the Header component. On the JavaScript side, it's defined as a helper component within Header.js, and not exported anywhere. It might be tempting to declare a class name myapp-LoginForm, and sneak that into both Header.js and Header.scss. But let's say the new guy on the team is be tasked to fix a small layout issue in the login form, and inspects the element to figure out where to start. There is no LoginForm.js or LoginForm.scss to be found, and he has to resort to grep or guesswork to find the relevant source files. That is to say, if the login form warrants a separate namespace, split it into a separate component. Consistency is worth its weight in gold in projects of non-trivial size.

So we've established our namespacing conventions, and now want to use them to sandbox our UI components. If every component only uses class names prefixed with their unique namespace, we can be sure that their styles never leak to their neighbors. This is very effective (see below for the caveats), but having to type the namespace over and over again also gets rather tedious.

A robust, yet still tremendously simple solution to this is to wrap the entire style file into a prefix block. Note how we only have to repeat the app and component names once:

.myapp-Header {

background: black;

color: white;

&-link {

color: blue;

}

&-signup {

border: 1px solid gray;

}

}The above example is in SASS, but the & symbol — perhaps shockingly — works the same across all relevant CSS preprocessors (SASS, PostCSS, LESS and Stylus). For completeness, this is what the above SASS compiles to:

.myapp-Header {

background: black;

color: white;

}

.myapp-Header-link {

color: blue;

}

.myapp-Header-signup {

border: 1px solid gray;

}All the usual patterns play well with this, e.g. having different styles for different component states (think Modifier in BEM terms):

.myapp-Header {

&-signup {

display: block;

}

&-isScrolledDown &-signup {

display: none;

}

}Which compiles to:

.myapp-Header-signup {

display: block;

}

.myapp-Header-isScrolledDown .myapp-Header-signup {

display: none;

}Even media queries work conveniently, as long as your preprocessor supports bubbling (SASS, LESS, PostCSS and Stylus all do):

.myapp-Header {

&-signup {

display: block;

@media (max-width: 500px) {

display: none;

}

}

}Which becomes:

.myapp-Header-signup {

display: block;

}

@media (max-width: 500px) {

.myapp-Header-signup {

display: none;

}

}The above pattern makes it very convenient to use long, unique class names without having to keep typing them over and over again. Convenience is mandatory, because without convenience, we will cut corners.

This document is about styling conventions, but the styles don't exist in a vacuum: our JS side will need to produce the same namespaced class names, and convenience is mandatory there as well.

As a shameless plug, I have created a very simple, 0-dependency JS library for exactly this, called css-ns. When combined at the framework level (with e.g. React), it allows you to enforce a specific namespace within a specific file:

// Create a namespace-bound local copy of React:

var { React } = require('./config/css-ns')('Header');

// Create some elements:

<div className="signup">

<div className="intro">...</div>

<div className="link">...</div>

</div>Will render into the DOM as:

<div class="myapp-Header-signup">

<div class="myapp-Header-intro">...</div>

<div class="myapp-Header-link">...</div>

</div>This is very convenient, and above all makes the JS side local by default.

But again, I digress. Back to the CSS side of things.

Remember when I said prefixing each class name with the component namespace was a "very effective" way of sandboxing styles? Remember when I said there were "caveats"?

Consider the following styles:

.myapp-Header {

a {

color: blue;

}

}And the following component hierarchy:

+-------------------------+

| Header |

| |

| [home] [blog] [kittens] | <-- these are <a> elements

+-------------------------+

We're cool, right? Only the <a> elements inside Header get blued, because the rule we generate is:

.myapp-Header a { color: blue; }But consider the layout is later changed to:

+-----------------------------------------+

| Header +-----------+ |

| | LoginForm | |

| | | |

| [home] [blog] [kittens] | [info] | | <-- these are <a> elements

| +-----------+ |

+-----------------------------------------+

The selector .myapp-Header a also matches the <a> element inside LoginForm, and we've blown our style isolation. As it turns out, wrapping all styles in a namespace block is an effective way for isolating a component from its neighbors, but not always from its children.

This can be fixed in two ways:

- Never target element names in stylesheets. If every

<a>element inHeaderis<a class="myapp-Header-link">instead, we'll never have to deal with this issue. Then again, sometimes you have the perfectly semantic markup set up, with the<article>s and<aside>s and<th>s in all the right places, and you don't want to clutter them with extra classes. In that case: - Only target things outside your namespace with the

>combinator.

Adjusted for the latter approach, our styles can be rewritten as:

.myapp-Header {

> a {

color: blue;

}

}Which will ensure our isolation also works depth-wise in the component tree, as the generated selector becomes .myapp-Header > a.

If this sounds controversial, let me further bring up your blood pressure by claiming that this is also fine:

.myapp-Header {

> nav > p > a {

color: blue;

}

}We've been trained to avoid selector nesting (including this stronger form with >) like the plague, by many years' worth of credible advice. But why? The cited reasons boil down to these three:

- Cascading styles will ruin your day, eventually. The more you nest selectors, the higher the chances of accidentally finding an element which matches the selectors of more than one component. If you've read this far, you know we've already eliminated this possibility (with strict namespace prefixing, and using strong child selectors where needed).

- Too much specificity will reduce reusability. The styles written for

nav p awon't be reusable anywhere else except in that very specific environment. But we specifically never want this anyway, in fact, we go out of our way to forbid this method of reusability, as it doesn't play well with our goal of components being isolated from each other. - Too much specificity will make refactorings harder. This has some basis in reality, in that if you only had

.myapp-Header-link a, you could freely move the<a>around in your component's HTML, and the same styles will always apply. Whereas with> nav > p > ayou will need to update the selector to match the link's new location within the component's HTML. But given how we want to assemble our UI from small, well-isolated components, this argument is also rather moot. Sure, if you had to consider the HTML & CSS of your entire application when doing a refactoring, this might be scary. But you're operating in a small sandbox which has some tens of lines of styles, and knowing that nothing outside that sandbox needs to be considered, these types of changes become a non-issue.

This is a good example of understanding the rules, so you know when to break them. In our architecture, selector nesting is not only OK, it's sometimes the right thing to do. Go crazy with it.

So have we achieved perfect sandboxing of our styles, so that each component can live in total isolation from the rest of the page? As a quick recap:

-

We've prevented leaks out of our components by prefixing each class name with the component namespace:

+-------+ | | | -----X---> | | +-------+ -

By extension, this means we've prevented leaks between our components:

+-------+ +-------+ | | | | | ------X------> | | | | | +-------+ +-------+ -

And we've prevented leaks into child components by minding our child selectors:

+---------------------+ | +-------+ | | | | | | ----X------> | | | | | | | +-------+ | +---------------------+ -

But crucially, external styles can still leak into components:

+-------+ | | ----------> | | | +-------+

For example, say we have styled our component with:

.myapp-Header {

> a {

color: blue;

}

}But then we include an ill-behaving 3rd party library which introduces the following CSS:

a {

font-family: "Comic Sans";

}There is no simple way to protect your components from such external abuse, and this is where we often need to just:

Luckily, you often have some control over the dependencies you use, and can simply look for a more well-behaved alternative.

Also, I said there's no simple way to protect your components from this. That doesn't mean there aren't ways. There are ways, dude, they just come with various trade-offs:

- Just brute-forcing it: if you include a CSS reset for every element of every component, and attach it to a selector that always wins over the 3rd party ones, you're golden. But unless your application is tiny (say, a "Share" button 3rd parties can embed onto their sites), this approach quickly spirals out of control. This is rarely a good idea, it's just listed here for completeness.

all: initialis a less-known new CSS property designed for exactly this. It can stop inherited properties from flowing in, and also work as a local reset, as long as it wins the specificity war (and as long as you repeat it for each element you want to protect). Its implementation includes some intricacies and isn't yet supported everywhere, butall: initialmight eventually become a useful tool for style isolation.- Shadow DOM has already been mentioned, and it's exactly the tool you would want for this job, as it allows declaring clear component boundaries for both JS and CSS. Despite some recent glimmers of hope, the Web Components spec hasn't made great progress in recent years, and unless you're working with a known set of browsers you can't really count on the Shadow DOM.

- Finally, there's the

<iframe>. It offers the strongest form of isolation the web runtime can offer (both for JS and CSS), but also carries steep penalties in startup cost (latency) and maintenance cost (retained memory). Still, oftentimes the trade-off is worth it, and most prominent web embeds (Facebook, Twitter, Disqus, etc) are in fact implemented with iframes. For the purposes of this document however — isolating hundreds or thousands of small components from each other — this approach would blow our performance budget a 100 times over.

Anyway, this aside is running long, back to our list of CSS rules.

Exactly like we styled .myapp-Header > a, when we nest components, we may need to apply some styles to child components (the Web Component analogy is again perfect, as then there'd truly be no distinction between how > a and > my-custom-a work). Consider this layout:

+---------------------------------+

| Header +------------+ |

| | LoginForm | |

| | | |

| | +--------+ | |

| +--------+ | | Button | | |

| | Button | | +--------+ | |

| +--------+ +------------+ |

+---------------------------------+

We immediately see that styling .myapp-Header .myapp-Button would be a bad idea, and we'd obviously want .myapp-Header > .myapp-Button instead. But what styles would we ever want to apply to child components?

Note how the LoginForm is docked to the right edge of the Header. Intuitively, one might style this as:

.myapp-LoginForm {

float: right;

}We haven't violated any of our rules, but we've also made the LoginForm a lot harder to reuse: if our upcoming home page wants to repeat the LoginForm, but without the right-side float, we're out of luck.

The pragmatic solution to this is to (partially) relax our previous rule of only applying styles to the namespace the current file belongs to. Specifically, we want to do this instead:

.myapp-Header {

> .myapp-LoginForm {

float: right;

}

}This is in fact perfectly OK, as long as we don't allow breaching the child's sandbox arbitrarily:

// COUNTER-EXAMPLE; DON'T DO THIS

.myapp-Header {

> .myapp-LoginForm {

color: blue;

padding: 20px;

}

}We don't want to allow this, because we'd lose our safety net of local changes never having global repercussions. With the above code, LoginForm.scss is no longer the only place you need to check when modifying the appearance of the LoginForm component. Making changes gets scary again. So where do we draw the line between what's OK and what's a no-no?

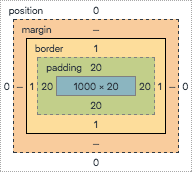

We want to respect the sandbox inside each child component, as we don't want to rely on its implementation details. It's a black box to us. What's outside the child component, conversely, is the sandbox of the parent, where it reigns supreme. The distinction between inside and outside emerges quite naturally from one of the most fundamental concepts in CSS: the box model.

My analogies are terrible, but here goes: just like being inside a country means being within its physical borders, we establish that a parent can effect styles on its (direct) children only outside the border of the component. That means properties related to positioning and dimensions (e.g. position, margin, display, width, float, z-index etc) are OK, while properties that reach inside the border (e.g. border itself, padding, color, font etc) are a no-no.

As a corollary, this is also very obviously forbidden:

// COUNTER-EXAMPLE; DON'T DO THIS

.myapp-Header {

> .myapp-LoginForm {

> a { // relying on implementation details of LoginForm ;__;

color: blue;

}

}

}There are a few interesting/boring edge cases, such as:

box-shadow- A specific type of shadow can be an integral part of the look-and-feel of a component, and thus it should contain those styles itself. Then again, the visual effect is clearly rendered outside the border, so it's going into its parent component's territory.color,fontand other inherited properties -.myapp-Header > .myapp-LoginForm { color: red }reaches into the insides of the child component, but on the other hand can be functionally equivalent to.myapp-Header { color: red; }, which is OK by our other rules.display- If the child component uses a Flexbox layout, it's possibly relying on havingdisplay: flexset on its root element. However, the parent might choose to hide its child by settingdisplay: noneon it.

The important thing to realize is that in these edge cases, you're not risking thermonuclear war, just introducing a tiny bit of the CSS cascade back into your styles. As with other things that are bad for you, enjoying the cascade in moderation is fine. For instance, taking a closer look at the last example, the specificity contest works out exactly like you'd want it to: when the component is visible, .myapp-LoginForm { display: flex } is the most specific rule, and takes precedence. When the owner decides to hide it with .myapp-Header-loginBoxHidden > .myapp-LoginBox { display: none } that rule is more specific, and wins.

To avoid repetitive work, you sometimes need to share styles between components. To avoid work altogether, you sometimes want to use styles created by others. Both of these should be achieved without creating any unnecessary coupling into the codebase.

As a concrete example, let's consider using some styles from Bootstrap, as it's a perfect example of an annoying framework to work with. Considering everything we've talked about above, with regard to sharing a single global namespace for styles, and collisions being bad, Bootstrap:

- Exports a ton of selectors (as of version 3.3.7, 2481 to be precise) to that namespace, whether you actually use them or not. (Fun aside: IE's up to version 9 can only process 4095 selectors before silently ignoring the rest. I've heard of people spending days debugging this wondering what the hell's going on.)

- Uses hard-coded class names such as

.btnand.table. Can't imagine those ever being accidentally reused by some other developer or project. :sarcasm:

Regardless, let's say we want to use Bootstrap as a basis for our Button component.

Instead of integrating on the HTML side with:

<button class="myapp-Button btn">Consider extending the class in your styles:

<button class="myapp-Button">.myapp-Button {

@extend .btn; // from Bootstrap

}This has the benefit of not giving anyone (including yourself) any ideas about relying on the presence of the ridiculously named btn class on the HTML component. The origin of the styles that Button uses is an implementation detail that need not show on the outside at all. As a consequence, should you ever decide to ditch Bootstrap in favor of another framework (or just writing the styles yourself), the change won't be externally visible in any way (except, uhh, the visible changes in how Button looks).

The same principle applies to your own helper classes, and there you'll have the option of using more sensible class names:

.myapp-Button {

@extend .myapp-utils-button; // defined elsewhere in your project

}Or forgoing emitting the class altogether (supported by most preprocessors):

.myapp-Button {

@extend %myapp-utils-button; // defined elsewhere in your project

}Finally, all CSS preprocessors support the concept of mixins, which are a tremendously powerful tool:

.myapp-Button {

@include myapp-generateCoolButton($padding: 15px, $withExplosions: true);

}It should be noted that when dealing with more civilized style frameworks (such as Bourbon or Foundation), they'll in fact be doing just this: declaring a bunch of mixins for you to use where they're needed, and not emitting any styles on their own. Neat.

Know the rules, so you know when to break them

Finally, as mentioned before, when you understand the rules you've laid out (or adopted from a stranger on the Internet), you can make exceptions that make sense to you. For instance, if you feel that there's added value in using a helper class directly, you can do so:

<button class="myapp-Button myapp-utils-button">That added value might be — for instance — that your test framework can then be more clever in automatically figuring out what things act as buttons, and can be clicked on.

Or you might decide that it's OK to break component isolation when the breach is tiny, and the additional work from splitting components would be too great. While I'll want to remind you that it's a slippery slope and that consistency is king et cetera, as long as your team is in agreement, and you get stuff done, you're doing the right thing.

If you liked this article, you could totally tweet about it! Or not.