In this article, I would like to introduce readers to the realm of cloud-native technologies by demonstrating how to implement a fully custom operator using Go and Kubebuilder, with a sprinkle of React and numerous CLI tools for a full-stack experience. While I don't consider myself an expert in this field, I believe that during my internship at Cisco, I acquired enough knowledge to share some useful insights on this topic and hopefully dispel some misconceptions about its complexity.

To make this guide more reflective of the actual process one would follow when meaningful work is required, I will focus on aspects that go beyond simply achieving a "hello world" type of result. In this writing, we will create an operator that uses Grype to assess the current security status of our Kubernetes cluster.

The source code of the entire project is available on Github

Containerization is a lightweight virtualization method that packages applications and their dependencies into self-contained units called containers. This approach enables efficient resource usage, rapid deployment, and easy scaling compared to virtual machines (VMs). The advantage over traditional VMs is that workloads are processes that utilize lightweight operating system (OS) APIs (application programming interfaces) for compatibility, rather than full-fledged operating systems. As a result, they share a common kernel with the host OS, which achieves these beneficial properties. Containers are portable between different environments, immutable, and isolated.

It started as a continuation of Borg, which was Google's original internal container cluster manager that, at one point, ran most of their systems. Today, Kubernetes is the most widely used open-source container orchestration tool, providing higher-level concepts that Docker or other runtimes conforming to OCI do not offer. These concepts include self-healing, manual and automatic horizontal scaling, load balancing, and automated rollouts and rollbacks, to name a few. Figuratively speaking, it serves as the navigator for Docker containers; hence, its name means 'steersman' or 'pilot' (grc: κυβερνήτης).

Nodes are physical or virtual machines that provide computing resources for the cluster they are part of in order to run applications and services. New nodes can be added to a cluster, and existing ones can be removed. Hosted workloads can be moved arbitrarily from one node to other nodes during maintenance.

At a minimum, a cluster contains a control plane and one or more compute machines, or nodes. The control plane is responsible for maintaining the desired state of the cluster, such as which applications are running and which container images they use. Nodes are the ones that actually run the applications and workloads. See: https://www.redhat.com/en/topics/containers/what-is-a-kubernetes-cluster

Namespaces are cluster-wide unique resources used to create a virtual separation between components. The name, namespace, and kind triad uniquely identifies every resource within a cluster. We will take advantage of this later when I discuss the operator.

Pods are arguably the most important resource within Kubernetes, as they incorporate one or more containers that can potentially share storage and network resources. They are considered the smallest deployable unit of computing since Kubernetes does not manage containers alone. Other important resources include ReplicaSets, which ensure that the requested number of identical pods are running at a given time, and Deployments, which incorporate ReplicaSets and provide mechanisms for rolling updates and rollbacks to minimize application downtime.

Each pod has a unique IP address, so if one group of pods wants to communicate with another, all the other pods must know how to reach them. However, the number of pods can change dynamically due to their ephemeral nature. This problem is solved by the Service resource, which provides a facade or abstraction over multiple pods that are selected by tags.

An Ingress is a resource used to manage external access to services within a Kubernetes cluster, typically for HTTP and HTTPS traffic. It allows you to define rules for routing client requests to the appropriate services based on hostnames, paths, or other factors. Unlike other methods of exposing services, such as NodePort or LoadBalancer, Ingress consolidates routing rules into a single point of control, simplifying the management of traffic to multiple services. An Ingress controller, which operates as a reverse proxy, is necessary to implement these rules and manage load balancing, SSL termination, and traffic routing within the cluster.

Controllers in Kubernetes are automations that have access to the Kubernetes API and other resources—often outside the cluster—in order to observe the state of the cluster and act on changes according to the logic with which they were implemented. Operators are essentially controllers that define a CRD (Custom Resource Definition), making them an effective way to extend the functionality of Kubernetes.

Read more: https://kubernetes.io/docs/concepts/architecture/controller/

First, we need to ensure that we have the most recent stable versions of Go and kubectl. Kubectl is essentially a command-line interface tool that allows us to run commands in a given cluster. In this case, we communicate with the Kubernetes API server component via its REST protocol.

Each operating system has its own method for installing and managing these packages, but if you do not need the newest version due to a specific new feature, it is more convenient to rely on the package provided by your distribution rather than what a dedicated version manager like gvm can offer. As long as the benefits do not outweigh the extra work required to manage things, we should opt for the default option for simplicity.

$ go version

go version go1.23.0 linux/amd64$ kubectl version

Client Version: v1.30.4

Kustomize Version: v5.0.4-0.20230601165947-6ce0bf390ce3

Server Version: v1.31.0Furthermore, we will need helm which I will introduce later.

$ helm version

version.BuildInfo{Version:"v3.16.1", GitCommit:"5a5449dc42be07001fd5771d56429132984ab3ab", GitTreeState:"clean", GoVersion:"go1.22.7"}We will use Kubebuilder, which is a framework for building Kubernetes APIs using custom resource definitions (CRDs). It streamlines the process of developing Kubernetes controllers by providing a set of tools, libraries, and code generation features. Built on top of the Kubernetes controller-runtime library, it enables developers to create robust, scalable controllers and operators with minimal boilerplate code. It supports best practices such as testing, scaffolding, and project layout, making it easier to manage and extend Kubernetes-native applications.

We can download the latest release of the Kubebuilder CLI, make it executable, and move it into /usr/local/bin, where user-installed binaries are typically stored.

curl -L -o kubebuilder "https://go.kubebuilder.io/dl/latest/$(go env GOOS)/$(go env GOARCH)"

chmod +x kubebuilder

sudo mv kubebuilder /usr/local/bin/After that we should be able to use Kubebuilder.

$ kubebuilder version

Version: main.version{KubeBuilderVersion:"4.1.1", KubernetesVendor:"1.30.0", GitCommit:"e65415f10a6f5708604deca089eee6b165174e5e", BuildDate:"2024-07-23T07:11:14Z", GoOs:"linux", GoArch:"amd64"Binaries installed by the go install command are placed into $(go env GOPATH)/bin which is usually equal to ~/go/bin.

We can make these commands callable by putting this directory onto our $PATH if needed.

printf '\nexport PATH="$(go env GOPATH)/bin:$PATH"\n' >> ~/.zshrc

exec zsh # Reinitializing our shell in order to make this change effectfulAfter that we can initialize a new project with a domain name of our choice and a github repository URL which will be the name of our Go module that we will be working on.

kubebuilder init --domain zoltankerezsi.xyz --repo github.com/kerezsiz42/scanner-operator2Then we create an API with a group, version and kind name.

kubebuilder create api --group scanner --version v1 --kind ScannerAfter these steps, we will have a scaffold generated in the internal/controller folder for us. The two most important methods are the Reconciler and the SetupWithManager, which we will examine in more depth later.

Additionally, to set up a cluster, we can use a tool called kind, which makes it easy to create and delete Kubernetes clusters and nodes for our development. When using kind, the nodes run as Docker containers instead of virtual machines in the cloud.

go install sigs.k8s.io/[email protected]

kind create clusterWe can verify if kubectl is configured correctly for this cluster.

$ kubectl cluster-info --context kind-kind

Kubernetes control plane is running at https://127.0.0.1:37675

CoreDNS is running at https://127.0.0.1:37675/api/v1/namespaces/kube-system/services/kube-dns:dns/proxyWe can modify the ScannerReconciler structure and its methods to implement our initial testing logic, explore the workings of kubebuilder, and become familiar with the development workflow. Firstly, since we will need a separate HTTP API outside of the one used for metrics, we can add an http.Server field to the ScannerReconciler struct, which will be zero-initialized (meaning it will be nil at the beginning).

// internal/controller/scanner_controller.go

type ScannerReconciler struct {

client.Client

Scheme *runtime.Scheme

Server *http.Server

}The Kubebuilder team has kindly marked the place where we should put our code, so we will start the HTTP server there. Here, we define a single handler function that returns the string "Hello, world!" and start the server in a goroutine, since http.Server.ListenAndServe() is a blocking call. We use os.Exit(1) together with log.Error() instead of panic(), just as in cmd/main.go, for failures that make further continuation of the process impossible. We intentionally allow the process to die, as it will be restarted by the Deployment anyway. Additionally, the convention is to start error messages with lowercase letters. After the first reconciliation is complete, the HTTP server should be running on port 8000, and the logs of the controller-manager pod should contain the "successfully reconciled" message.

// internal/controller/scanner_controller.go

func (r *ScannerReconciler) Reconcile(ctx context.Context, req ctrl.Request) (ctrl.Result, error) {

reconcilerLog := log.FromContext(ctx)

if r.Server == nil {

mux := http.NewServeMux()

mux.Handle("/", http.HandlerFunc(func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

if _, err := fmt.Fprintf(w, "Hello, world!\n"); err != nil {

reconcilerLog.Error(err, "error while handling request")

os.Exit(1)

}

}))

r.Server = &http.Server{Addr: ":8000", Handler: mux}

go func() {

if err := r.Server.ListenAndServe(); err != nil && err != http.ErrServerClosed {

reconcilerLog.Error(err, "unable to start HTTP server")

os.Exit(1)

}

}()

}

reconcilerLog.Info("successfully reconciled")

return ctrl.Result{}, nil

}Kustomize is a tool for customizing Kubernetes configurations. It allows us to generate resources from other resources and set cross-cutting fields for resources, along with composing and customizing collections of resources, as documented on the official Kubernetes docs website. It is used here to create a more concise version of the Kubernetes resource files by minimizing the amount of duplicated content, thereby simplifying maintenance. In this project, the config folder is filled with such resource definitions.

In the config/default/kustomization.yaml file, we can set the namespace where the controller resources will be placed and a name prefix for these resources. Furthermore, the resources section contains references to other kustomization files that will need to be processed, such as the RBAC (Role-Based Access Control) rules and the CRD itself. Even though we will only have a single instance of the controller-manager, it is still good practice to create a Service for it. To achieve this, we will create a new file named config/default/api_service.yaml and add it to the kustomization resources. The final service looks like the following:

apiVersion: v1

kind: Service

metadata:

labels:

control-plane: controller-manager

app.kubernetes.io/name: scanner-operator2

app.kubernetes.io/managed-by: kustomize

name: controller-manager-api-service

namespace: system

spec:

ports:

- name: http

port: 8000

protocol: TCP

targetPort: 8000

selector:

control-plane: controller-managerSo thanks to kustomize name will be prefixed with scanner- and the namespace will be replaced with scanner-system once the resource is applied.

We can change the default imagePullPolicy from Always to IfNotPresent implicitly by changing the image tag from latest to dev in our Makefile. Doing this will prevent Kubernetes from always trying to pull the image when we run make deploy later. We will also set a proper GitHub Container Registry address so that we can push the built image there to be used by the packaged version of our software.

IMG ?= ghcr.io/kerezsiz42/scanner-operator2:dev.PHONY: kind-load

kind-load:

kind load docker-image ${IMG}make docker-build # Build the docker image

make docker-push # Optionally push the image to the registry. This step is only needed if we want to test the helm deployment.

make kind-load # Load the new docker image into kind cluster

make deploy # Deploy or redeploy all resources that are needed for the newest versionkubectl api-resources --verbs=list -o name | grep scannerAfter this, there should be a pod named scanner-controller-manager with a Running status, along with the new service we just defined, the metrics service, deployment, and replicaset.

$ kubectl get all -n scanner-system

NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE

pod/scanner-controller-manager-777b874846-c2tpw 1/1 Running 0 25m

NAME TYPE CLUSTER-IP EXTERNAL-IP PORT(S) AGE

service/scanner-controller-manager-api-service ClusterIP 10.96.21.245 <none> 8000/TCP 25m

service/scanner-controller-manager-metrics-service ClusterIP 10.96.174.233 <none> 8443/TCP 25m

NAME READY UP-TO-DATE AVAILABLE AGE

deployment.apps/scanner-controller-manager 1/1 1 1 25m

NAME DESIRED CURRENT READY AGE

replicaset.apps/scanner-controller-manager-777b874846 1 1 1 25mWe can access the logs outputted by the controller-manager using the kubectl logs command. Once we have ensured that the controller-manager pod is running properly, we can apply our new scanner resource described in the file at config/samples/scanner_v1_scanner.yaml. Then, to manually test the API, we will use the kubectl port-forward command to make the previously defined service accessible on our host machine.

kubectl apply -f config/samples/scanner_v1_scanner.yaml

kubectl port-forward service/scanner-controller-manager-api-service -n scanner-system 8000:8000Using the curl command we can verify the result from our 'backend'.

$ curl localhost:8000

Hello, world!Helm is currently the industry standard package manager for Kubernetes, so we will use it to create our packaged operator that can later be downloaded, deployed, and undeployed in a Kubernetes namespace, similar to Istio, without the need for the source code or manually running make install and make deploy on every change.

Helmify is a tool that creates Helm charts from Kubernetes manifests (the YAML files). When running make helm, it generates a Helm chart in the chart directory of our repository. Our task here consists of copying the appropriate Makefile commands from the documentation and executing them correctly when we create a new version of our software.

.PHONY: helm

helm: manifests kustomize helmify

$(KUSTOMIZE) build config/default | $(HELMIFY)After this, we should be able to try out the deployment using Helm. To start with a clean slate, we can recreate the cluster and manually create the new scanner-system namespace, which will be used by the chart, and install it there. Of course, kind does not have access to the Docker image, so we will need to load it again.

make helm # Generate the up-to-date helm chart within the ./char folder

kind delete cluster && kind create cluster

# If the image is not present, then pull it: "docker pull ghcr.io/kerezsiz42/scanner-operator2:dev"

make kind-load # Load image into the kind cluster

kubectl create namespace scanner-system

helm install scanner ./chart -n scanner-system # Or "helm install scanner --repo https://github.com/kerezsiz42/scanner-operator2/tree/main/chart -n scanner-system"We can verify that it is working the same way as before by calling the base endpoint, which replies with the "Hello, world!" message exactly as we programmed.

kubectl apply -f config/samples/scanner_v1_scanner.yaml

kubectl port-forward service/scanner-chart-controller-manager-api-service -n scanner-system 8000:8000

$ curl localhost:8000

Hello, world!To remove the deployment, we run the helm uninstall command and can optionally remove the namespace as well. By using Helm, we can take advantage of its many benefits, including dependency management, release management, and parameterization. All these features are essential for considering our project ready for industrial use.

helm uninstall scanner -n scanner-system

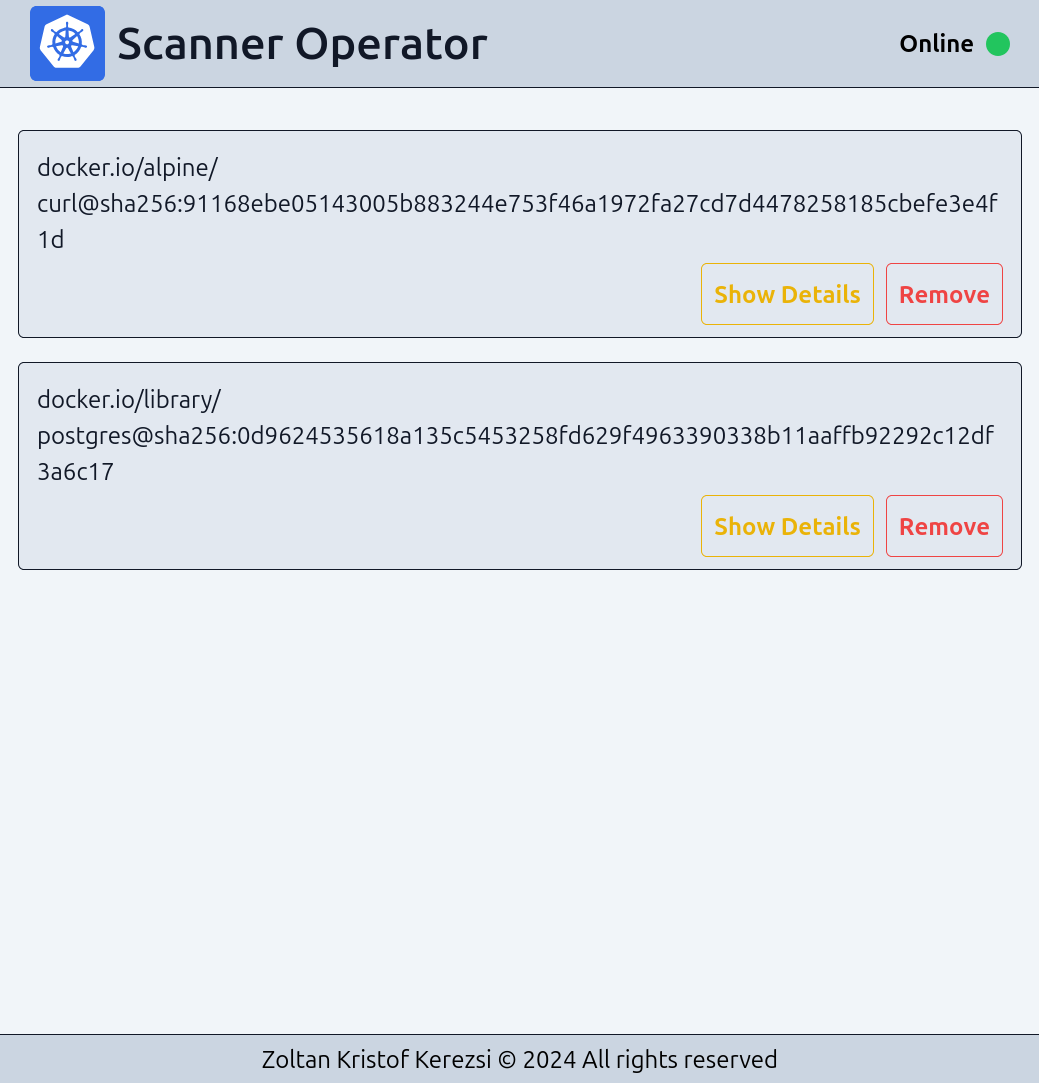

kubectl delete namespace scanner-systemThe UI that we assemble here is considered a test or proof that the operator functions as intended and performs reasonably well. Discussing this may be seen as a deviation from the original goal, but for the sake of testing, it might still be worthwhile to implement a proper UI.

For simplicity, I have chosen to develop this UI using React, as the tooling around it is very mature. Additionally, we will be using Node instead of newer, more modern JavaScript runtimes like Bun or Deno. While these are mostly functionally compatible with Node, there could still be some rough edges or surprising challenges when trying to achieve an exact result, at least as of the time of this writing.

Node can also be installed using a preferred version manager like nvm or fnm. I will be using the latest release available at the time of writing this document.

$ node --version

v22.6.0The first thing we should do is initialize the project within a frontend directory and install the necessary dependencies using npm.

mkdir frontend

cd frontend

npm init -y

npm install esbuild react react-dom @types/react-dom tailwindcss-

esbuild is a fast bundler for JavaScript and TypeScript. A bundler is a tool that takes multiple source code files and combines them into one or more files, depending on the configuration. Before the

importdirective was available, using a bundler was our only option for shipping code with multiple dependencies if we did not want to use globally scoped objects, as with jQuery. Now that module syntax is standardized, it is still useful to bundle our frontend code to minimize the number of network requests the browser has to make to gather all the source files and run our code. Another reason is, of course, that we use TypeScript, which is not directly runnable by the browser, so a transformation step is necessary. -

react,react-dom, and@types/react-domare the packages we need to use to have all the necessary components of React for the web when using TypeScript. -

tailwindcssis a utility-first CSS compiler that serves a purpose similar to that of a JavaScript bundler. It looks for files specified by the pattern intailwind.config.jsand searches for existing Tailwind class names specified in those files in order to include them in the finaloutput.css.

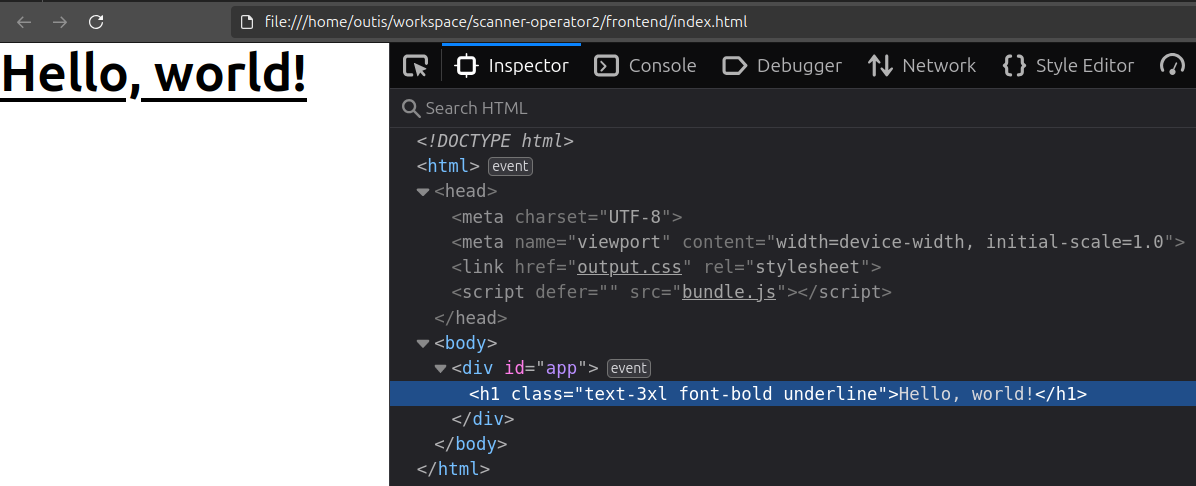

After that, we create the entry point of our single-page application, the index.html file. The <script /> tag, together with the defer keyword, is used to load the compiled frontend code, which will take over the <div /> element with the id of app once the complete HTML file has been received and attached to the DOM. Cascading style sheets are also loaded using the <link /> tag within the <head />.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8" />

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1.0" />

<link href="output.css" rel="stylesheet" />

<script defer src="bundle.js"></script>

</head>

<body>

<div id="app"></div>

</body>

</html>The initial version of our client-side code to test our frontend setup looks like the following:

import * as React from "react";

import ReactDOM from "react-dom/client";

const element = document.getElementById("app")!;

const root = ReactDOM.createRoot(element);

function App() {

return <h1 className="text-3xl font-bold underline">Hello, world!</h1>;

}

root.render(<App />);We also define some scripts in our package.json file to document the steps required to build the final JavaScript and CSS files, which can later be copied and served using an HTTP server. Here, we are using the "production" NODE_ENV environment variable, which instructs the bundler to omit program code that would allow us to attach certain debugging tools, such as the React Developer Tools, which make browsers aware of React's internal state and behavior. This value can be changed back at any time for debugging purposes.

{

"scripts": {

"build-css": "./node_modules/.bin/tailwindcss -i src/input.css -o output.css",

"build-js": "./node_modules/.bin/esbuild src/index.tsx --define:process.env.NODE_ENV=\\\"production\\\" --bundle --outfile=bundle.js",

"build": "npm run build-css && npm run build-js"

}

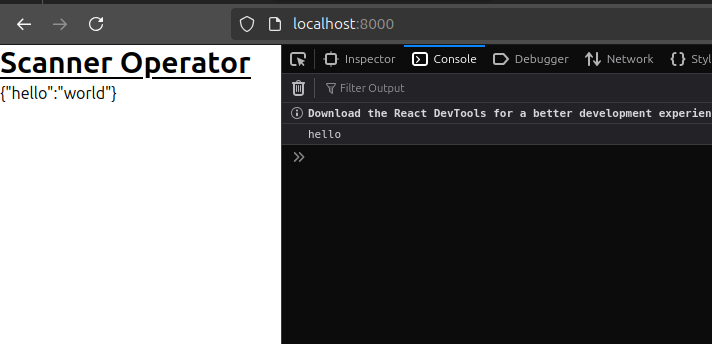

}The initial UI looks like the following in it's rendered form:

With all this done, we can confirm that with this setup, we can develop a modern UI with a fast and easy-to-understand iteration loop, as all components are configured correctly to generate the resulting JavaScript, CSS, and HTML files.

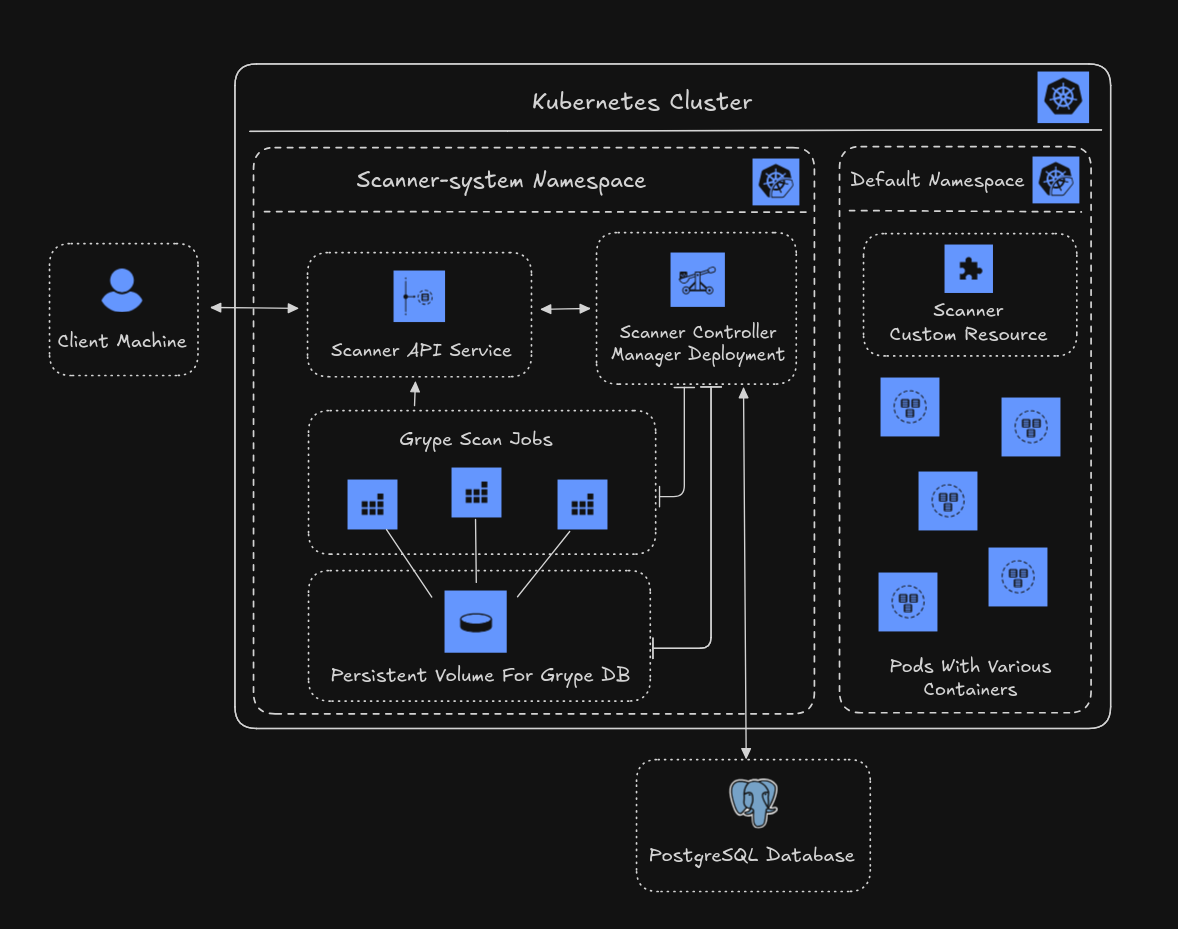

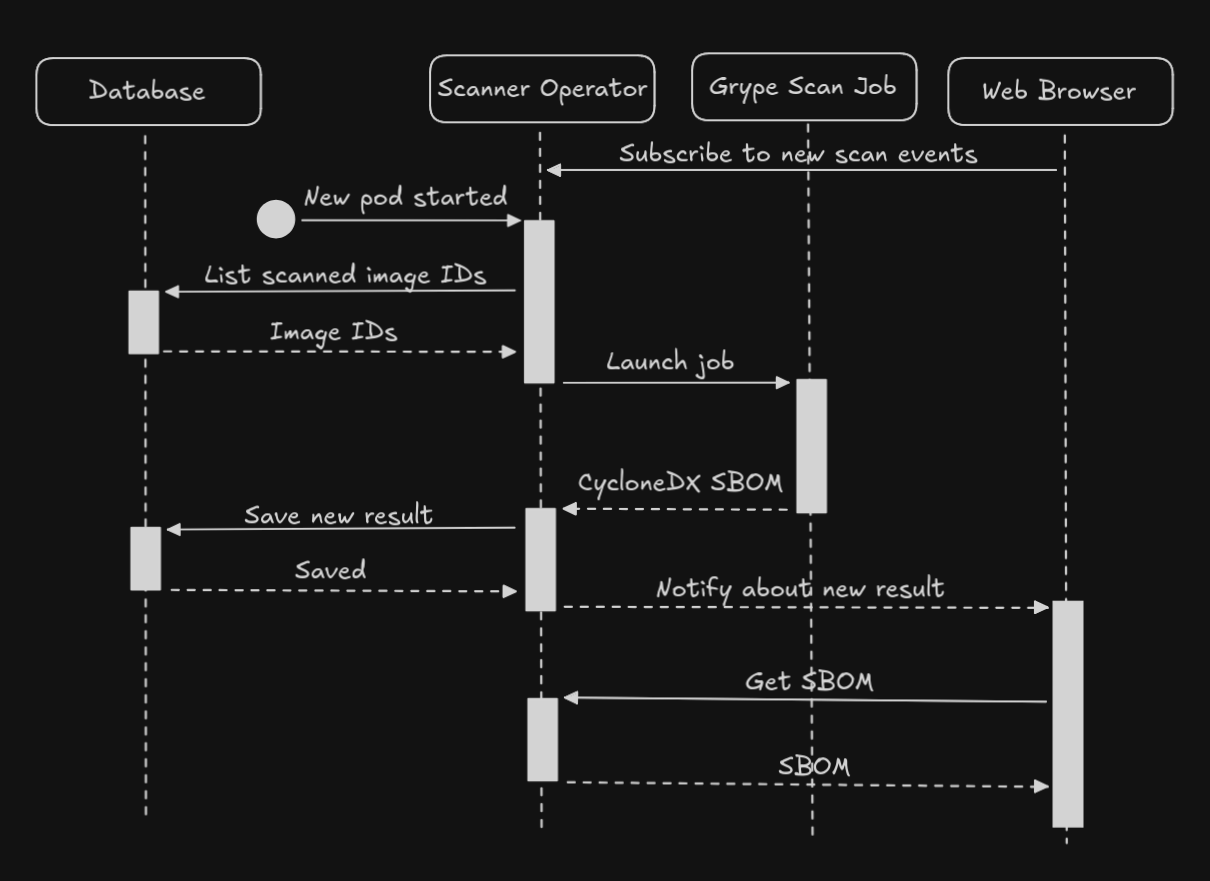

The goal of this operator is to provide constant feedback about the security status of our Kubernetes cluster. It collects and scans container images using an external tool that can run in a Pod and, consequently, as a Job. In our test, we will install the custom resource in the default namespace.

The controller-manager will be subscribed to certain events and will therefore be notified by the Kubernetes API each time a new Pod is started. It will check the connected database to determine whether it should start a new scan Job. Successful Jobs return their results by calling an endpoint on the REST API provided by the operator. The service that connects to the operator deployment can be accessed from the outside either through an ingress or by using port-forwarding.

We will utilize the publisher-subscriber architectural pattern, which is a commonly used communication method between components of distributed systems. The advantage of this approach is the loose coupling and scalability it provides, as well as the fact that subscribers receive faster—almost real-time—notifications when an event occurs, compared to polling, which would involve the client repeatedly calling the API and causing unnecessary traffic. When a client loads the frontend code, it automatically subscribes to scan events using WebSocket. Once such an event occurs, the client can load the results from the same REST API and display them in a list on the user interface.

We will be using Grype, which is a vulnerability scanner for container images and filesystems. It will handle the essence of the work. The scanning process results in a collection of CVEs, which highlight weaknesses in computational logic found in software and hardware components that, when exploited, can negatively impact the confidentiality, integrity, or availability of our product.

Grype supports multiple types of outputs, but among them, OWASP CycloneDX SBOM (software bill of materials)—an object model that shows a nested inventory or list of ingredients that make up software components—contains probably the most information, so we will use that. Fortunately, there is a Go library available to us that supports this format, so we can add it to our project dependencies:

go get github.com/CycloneDX/cyclonedx-go$ grype version

Application: grype

Version: 0.82.0

BuildDate: 2024-10-07T21:36:44Z

GitCommit: 6b09bb857564cd3c59c0cc1b6ea997c5ee198b6d

GitDescription: v0.82.0

Platform: linux/amd64

GoVersion: go1.23.2

Compiler: gc

Syft Version: v1.14.0

Supported DB Schema: 5When trying Grype multiple times using a Kubernetes Pod, a potential pitfall becomes obvious: Grype has to download its vulnerability database in each pod before performing the scan, resulting in an average delay of 30 seconds for each scan instead of a single initial delay. This is very wasteful. Attempting the same with the local CLI does not produce the same issue, as this database is cached in the filesystem. However, running two scans simultaneously before the database is present results in the failure of both.

kubectl run -it grype --image=anchore/grype -- python

kubectl delete pod grype

kubectl run -it grype --image=anchore/grype -- python # Downloads vulnerability db againUpon further inspection, we can see that Grype does provide a way to manage its database through subcommands, so this might be an additional responsibility that our operator could take on. However, it may be a better solution to avoid running jobs concurrently. Doing it this way makes throttling unnecessary, as not putting too much processing load on the cluster is also an important aspect of our goal.

REST stands for Representational State Transfer and is a set of architectural constraints that makes the job of designers, developers, and users of an application programming interface easier by providing a few loose rules to follow. RESTful systems are stateless, cacheable, have a layered structure, and, when paired with client applications, their inner workings are entirely decoupled.

To comply with today's standards, we implement the Backend API using oapi-codegen, which is a tool that allows us to generate boilerplate Go code from an OpenAPI 3.0 definition (here oapi_definition.yaml). This way, we can spend more time developing our business logic.

There is also a client-side code generator for TypeScript (openapi-ts) along with a matching HTTP client, but since the API will be very simple, we will only install the code generator to automatically generate the response objects for us, which we can later place anywhere as needed.

npm i openapi-typescriptAfter installing the new package we can set up an npm script, so that we do not have to remember the command every time:

// package.json

{

"scripts": {

"gen": "./node_modules/.bin/openapi-typescript ../internal/oapi/oapi_definition.yaml -o ./src/oapi.gen.d.ts"

}

}In this section, we will install the remaining dependencies and establish communication between the client and server side, as well as set up and manually test the database connection.

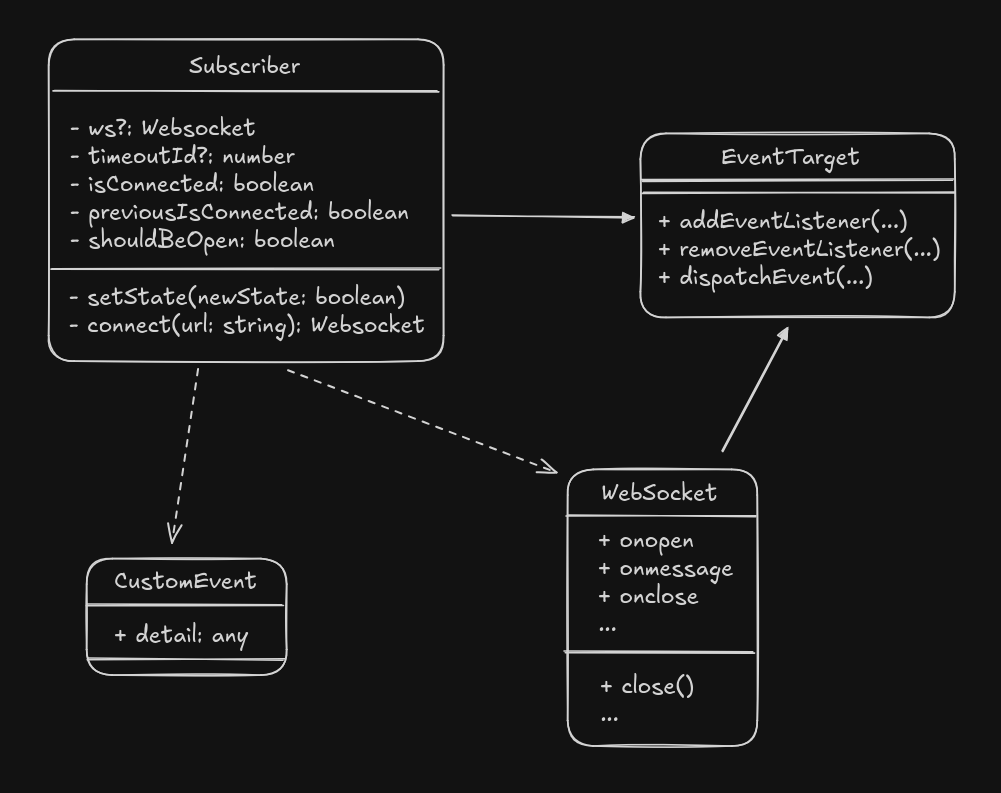

Contrary to the initial plans, we will use WebSockets instead of Webhooks. The reason for this is the performance gain that a continuously open TCP connection can provide over sending new HTTP requests for each scanned image to the subscribers. WebSocket is bidirectional by nature, but we will use it in a unidirectional way to notify clients about updates.

//@ts-check

/**

* @typedef {{signal?: AbortSignal}} SubscriberOptions

*/

export class Subscriber extends EventTarget {

/** @type {WebSocket | undefined} */

#ws = undefined;

/** @type {number | undefined} */

#timeoutId = undefined;

#isConnected = false;

#previousIsConnected = false;

#shouldBeOpen = true;

/**

* @param {string} url

* @param {SubscriberOptions} [options]

*/

constructor(url, options) {

super();

this.#ws = this.#connect(url);

options?.signal?.addEventListener("abort", () => {

this.#shouldBeOpen = false;

this.#ws?.close();

});

}

/**

* @param {boolean} newState

*/

#setState(newState) {

this.#previousIsConnected = this.#isConnected;

this.#isConnected = newState;

if (this.#previousIsConnected !== this.#isConnected) {

const ce = new CustomEvent("connection", { detail: this.#isConnected });

this.dispatchEvent(ce);

}

}

/**

* @param {string} url

* @returns {WebSocket}

*/

#connect(url) {

clearTimeout(this.#timeoutId);

const ws = new WebSocket(url);

ws.onopen = () => {

this.#setState(true);

};

/**

* @param {MessageEvent<string>} ev

*/

ws.onmessage = (ev) => {

const detail = JSON.parse(ev.data);

const ce = new CustomEvent("message", { detail });

this.dispatchEvent(ce);

};

ws.onclose = (_ev) => {

this.#setState(false);

if (this.#shouldBeOpen) {

this.#timeoutId = setTimeout(() => this.#connect(url), 5000);

}

};

return (this.#ws = ws);

}

}This component is a facade over the WebSocket client, which implements automatic reconnection and extends EventTarget to provide access to its "message" events. Using the addEventListener method, one can register a callback that processes the incoming CustomEvent object as it arrives. The connection can be closed using the web standard AbortSignal API. It operates under the assumption that the publisher will always send JSON strings, so it attempts to parse the incoming data accordingly.

This class is documented using JSDoc type annotations, which can be checked using the same TypeScript compiler as normal .ts files, so the two solutions are essentially equivalent, except that it is a valid .js file and the type annotations are comments. As a test, we can define an anonymous function in a useEffect hook. We create an AbortController that can be used to emit an abort signal when the component is unmounted from the DOM and register a function for the "message" event so that it prints the content to the console for now.

// frontend/src/index.tsx

useEffect(() => {

const ac = new AbortController();

const s = new Subscriber("/subscribe", { signal: ac.signal });

s.addEventListener("message", (e: CustomEventInit) => {

console.log(e.detail);

});

return () => ac.abort();

}, []);On the client side, fortunately, all modern browsers implement this feature. However, since the Go standard library does not include a WebSocket server, we need to introduce a new dependency: Gorilla WebSocket.

go get github.com/gorilla/websocketWe can create a new package and its folder called oapi within the internal folder, next to the controller, which will serve as a place to store everything related to OpenAPI and the code generation itself.

$ tree internal/oapi

internal/oapi

├── config.yaml

├── generate.go

├── oapi_definition.yaml

├── oapi.gen.go

└── oapi.go

1 directory, 5 filesHere, we are using the recommended 'tools go' approach, which means that instead of installing the oapi-codegen code generator as a binary external to our program, we introduce it into the version control system of go.mod to manage it as a dependency alongside our core application.

// internal/oapi/oapi.go

//go:build oapi

// +build oapi

package oapi

import (

_ "github.com/oapi-codegen/oapi-codegen/v2/cmd/oapi-codegen"

)This effectively enables us to call this CLI program through go run github.com/oapi-codegen/oapi-codegen/v2/cmd/oapi-codegen with the --config parameter and the path to our definition. In generate.go, we make use of the go:generate directive and Go's metaprogramming capabilities, which means that we can write program code using program code. This process is run by the programmer before compilation or build time, in other words, during development.

// internal/oapi/generate.go

package oapi

//go:generate go run github.com/oapi-codegen/oapi-codegen/v2/cmd/oapi-codegen --config=config.yaml oapi_definition.yamlNonetheless, we still need to include the runtime library of oapi-codegen which contains code that our generated code can make use of.

go get github.com/oapi-codegen/runtimeWe can configure it to generate only models from OpenAPI schemas and the ServerInterface with the appropriate methods that correspond to the paths section in our definition. Running the make gen command creates the oapi.gen.go file.

# internal/oapi/config.yaml

package: oapi

generate:

std-http-server: true

models: true

output: oapi.gen.goFirst, we define a new API endpoint in our OpenAPI 3.0 specification. The info section provides metadata, including the API version (1.0.0) and the title (Scanner Operator API). Under paths, the root path (/) is defined with a GET operation. The response for a successful GET request (HTTP status 200) is specified to return HTML content, with the content type set to text/html, and the response schema being a simple string. We will create such definitions for all of our endpoints, including the WebSocket as well. A great resource that can help us when specifying these definitions is the official Swagger documentation website.

# internal/oapi/oapi_definition.yaml

openapi: "3.0.0"

info:

version: 1.0.0

title: Scanner Operator API

paths:

/:

get:

responses:

"200":

description: Return the HTML part of the frontend

content:

text/html:

schema:

type: string

# ...Once the new oapi.gen.go file is created, we can make use of these structs and methods in our implementation class. Go's type safety ensures that in our implementation, all methods are defined in accordance with the generated ServerInterface. If our implementation is incorrect, the compiler will show a type mismatch at oapi.HandlerFromMux(), where the server implementation is used.

// internal/server/server.go

// ...

type Server struct {

db *gorm.DB

upgrader *websocket.Upgrader

}

func NewServer(db *gorm.DB) *Server {

return &Server{

db: db,

upgrader: &websocket.Upgrader{},

}

}

func (s *Server) Get(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

w.Header().Set("Content-Type", "text/html")

w.WriteHeader(http.StatusOK)

_, _ = w.Write(frontend.IndexHtml)

}

// ...Go modules are created by a go.mod file, which contains the module path—the GitHub repository path to our project, as generated by Kubebuilder. This allows other modules to reference and download ours through GitHub in order to use it. Modules contain packages (the folders), and packages contain the source files. Source files within a package have shared scope, so one file can access constants, variables, functions, and structs without additional importing.

Static files can be built into the binary as byte slices using the embed package, which is one of Go's unique features. We can place the embed.go file into the frontend folder and reference these variables under the frontend package name in internal/server, where we will build them into HTTP response handlers.

// frontend/embed.go

package frontend

import _ "embed"

//go:embed bundle.js

var BundleJs []byte

//go:embed index.html

var IndexHtml []byte

//go:embed output.css

var OutputCss []byteOf course all source files should be added to the final build, so we will have to make sure these are copied or added in the Dockerfile properly.

# ...

COPY frontend/bundle.js frontend/bundle.js

COPY frontend/index.html frontend/index.html

COPY frontend/output.css frontend/output.css

COPY frontend/embed.go frontend/embed.go

# ...To handle the WebSocket connection, we can define GetSubscribe, which manages WebSocket connections for a server. It upgrades an HTTP request to a WebSocket connection using s.upgrader.Upgrade, and if an error occurs, it logs the error and exits. Once the connection is successfully established, the function enters a loop where it sends the message "hello" to the client every 3 seconds using c.WriteMessage. If writing to the WebSocket connection fails, it logs the error and breaks the loop. The connection is closed once the function completes, thanks to the defer c.Close() statement.

// internal/server/server.go

// ...

func (s *Server) GetSubscribe(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

c, err := s.upgrader.Upgrade(w, r, nil)

if err != nil {

log.Print("upgrade:", err)

return

}

defer c.Close()

for {

data := []byte("\"hello\"")

if err := c.WriteMessage(websocket.TextMessage, data); err != nil {

log.Print("write:", err)

break

}

time.Sleep(3 * time.Second)

}

}In order to keep the project simple, we are not going to implement complex database migration capabilities, so Gorm’s AutoMigrate is more than sufficient. Essentially, we check on every startup if the database is clean and proceed with the migration. Otherwise, the service returns an error that the end user would eventually see.

// internal/database/dataabse.go

func GetDatabase() (*gorm.DB, error) {

databaseType := os.Getenv("DATABASE_TYPE")

dsn := os.Getenv("DSN")

dialector, err := GetDialector(databaseType, dsn)

if err != nil {

return nil, fmt.Errorf("failed to get dialector: %w", err)

}

db, err := gorm.Open(dialector, &gorm.Config{})

if err != nil {

return nil, fmt.Errorf("failed to connect to database: %w", err)

}

if err := db.AutoMigrate(&Hello{}); err != nil {

return nil, fmt.Errorf("failed to automigrate database: %w", err)

}

return db, nil

}Here, the GetDialector is simply a switch construct that, based on string comparison, returns the appropriate dialector instance—the component that defines the type of SQL database with which Gorm will communicate. Another point to note is that the GetDatabase function also accesses the DATABASE_TYPE and DSN (data source name) environment variables internally.

We also need to ensure that the Gorm library and the drivers we plan to use are all installed:

go get -u gorm.io/gorm

go get -u gorm.io/driver/sqlite

go get -u gorm.io/driver/mysql

go get -u gorm.io/driver/postgresAfter these modifications, the Reconcile method checks if the database connection (r.Db) is nil. If it is, it attempts to establish a connection using database.GetDatabase() and exits if the attempt fails. Similarly, if the HTTP server (r.Server) is not running, it creates a new server instance and starts it asynchronously. Errors that occur during server startup are logged, and the application exits if the server cannot be started. If both components are successfully initialized, the method logs a successful reconciliation and returns without errors.

// internal/controller/scanner_controller.go

func (r *ScannerReconciler) Reconcile(ctx context.Context, req ctrl.Request) (ctrl.Result, error) {

reconcilerLog := log.FromContext(ctx)

if r.Db == nil {

reconcilerLog.Info("connecting to database")

db, err := database.GetDatabase()

if err != nil {

reconcilerLog.Error(err, "unable to connect to database")

os.Exit(1)

}

r.Db = db

}

if r.Server == nil {

si := server.NewServer(r.Db)

m := http.NewServeMux()

r.Server = &http.Server{

Handler: oapi.HandlerFromMux(si, m),

Addr: ":8000",

}

go func() {

reconcilerLog.Info("starting HTTP server")

if err := r.Server.ListenAndServe(); err != http.ErrServerClosed {

reconcilerLog.Error(err, "unable to start HTTP server")

os.Exit(1)

}

}()

}

reconcilerLog.Info("successfully reconciled")

return ctrl.Result{}, nil

}To create a test database that our operator can connect to we can define the following deployment and service:

-

The deployment deploys a single replica of a PostgreSQL container (postgres:17-alpine) using an image from Docker Hub. The container exposes port 5432, the default PostgreSQL port. It sets up environment variables for the database user (

POSTGRES_USER), password (POSTGRES_PASSWORD), and database name (POSTGRES_DB). It uses an emptyDir volume mounted at /cache inside the container, which will persist data for the lifetime of the pod. -

The service exposes the PostgreSQL container to other services in the cluster via a Kubernetes Service named postgres-service. The service forwards traffic on port

5432(TCP) to the PostgreSQL pod, enabling access to the database.

# postgres.yaml

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

name: postgres

spec:

replicas: 1

selector:

matchLabels:

app.kubernetes.io/name: postgres

template:

metadata:

labels:

app.kubernetes.io/name: postgres

spec:

containers:

- name: postgres

image: postgres:17-alpine

imagePullPolicy: IfNotPresent

ports:

- containerPort: 5432

env:

- name: POSTGRES_PASSWORD

value: password

- name: POSTGRES_USER

value: user

- name: POSTGRES_DB

value: db

volumeMounts:

- mountPath: /cache

name: postgres-volume

volumes:

- name: postgres-volume

emptyDir: {}

---

apiVersion: v1

kind: Service

metadata:

name: postgres-service

spec:

selector:

app.kubernetes.io/name: postgres

ports:

- name: postgres

protocol: TCP

port: 5432

targetPort: 5432Since we decided to use environment variables to configure the database connection for our operator, we will need to add some default values in the config/manager/manager.yaml template. Within the containers definition, we can define an env object that contains the necessary default values. After making this change, we also need to run the make helm command to reflect these updates in the Helm chart's values.yaml file, which is where the end user will want to insert their own values.

# config/manager/manager.yaml

env:

- name: DATABASE_TYPE

value: postgres

- name: DSN

value: postgres://user:[email protected]:5432/dbFinishing all these things we can confirm that the necessary dependencies are all installed and configured to work together, so we can step over to the next phase of the implementation process.

In this chapter, we will review the main parts of the implemented operator and explain its purposes.

At the start, we have put some initializing logic into the Reconcile() method which is not the best place such cases since the cmd/main.go is the actual function that sets up the ScannerReconciler struct with the manager. Doing it this way the expressions do not have to be guarded by if statements of sync.Once constructs. Here we create a new JobObjectService connect to the database and pass the database reference to the newly created ScanService. The reconciler will need references of both services in order to list scanned images and launch new scans.

// cmd/main.go within the main function

jobObjectService, err := service.NewJobObjectService()

if err != nil {

mainLog.Error(err, "unable to create JobObjectService")

os.Exit(1)

}

mainLog.Info("connecting to database")

db, err := database.GetDatabase()

if err != nil {

mainLog.Error(err, "unable to connect to database")

os.Exit(1)

}

scanService := service.NewScanService(db)

s := &http.Server{

Handler: oapi.Handler(server.NewServer(scanService, mainLog)),

Addr: ":8000",

}

go func() {

mainLog.Info("starting Scanner API HTTP server")

if err := s.ListenAndServe(); err != http.ErrServerClosed {

mainLog.Error(err, "unable to start Scanner API HTTP server")

os.Exit(1)

}

}()

// ...

if err = (&controller.ScannerReconciler{

Client: mgr.GetClient(),

Scheme: mgr.GetScheme(),

JobObjectService: jobObjectService,

ScanService: scanService,

}).SetupWithManager(mgr); err != nil {

mainLog.Error(err, "unable to create controller", "controller", "Scanner")

os.Exit(1)

}The ScannerReconciler struct is placed into the internal/controller/scanner_controller.go file, so the previously mentioned services have to be defined in this one. We can make use of interfaces to promote abstraction and allows us to achive loose coupling of different parts of our codebase. In accordance with Liskov substitution interfaces ensure that derived classes (or implementing types) can be substituted for the interface without affecting correctness, maintaining consistency in behavior. What this all means is that ScannerReconciler should not and does not have any insight into the inner workings of its dependencies.

type ScannerReconciler struct {

client.Client

Scheme *runtime.Scheme

ScanService service.ScanServiceInterface

JobObjectService service.JobObjectServiceInterface

}The Reconcile method is part of the controller logic and is responsible for reconciling the actual state of a Kubernetes resource to match its desired state. It gets triggered when there are changes to the watched resources, taking a ReconcileRequest (identifying the resource) and returning a result or an error. Inside this method, you typically fetch the resource, analyze its current state, and issue Kubernetes API calls to create, update, or delete related objects to achieve the desired state. This loop ensures the system remains self-healing and eventually consistent with the declared specifications.

We start by fetching a Scanner resource identified by the req.NamespacedName and logs an error if the resource cannot be found, returning early if it is not a "not found" error. Then, it interacts with the ScanService to list scan results and logs any errors encountered while doing so. If the ScanService call fails, the code updates the status condition of the Scanner resource to Failed, ensuring the resource's state reflects the issue.

// internal/controller/scanner_controller.go:Reconcile()

func (r *ScannerReconciler) Reconcile(ctx context.Context, req ctrl.Request) (ctrl.Result, error) {

reconcilerLog := log.FromContext(ctx)

scanner := &scannerv1.Scanner{}

if err := r.Get(ctx, req.NamespacedName, scanner); err != nil {

reconcilerLog.Error(err, "unable to list scanner resources")

return ctrl.Result{}, client.IgnoreNotFound(err)

}

scanResults, err := r.ScanService.ListScanResults()

if err != nil {

reconcilerLog.Error(err, "failed to list scan results")

return ctrl.Result{}, r.nextStatusCondition(ctx, scanner, scannerv1.Failed)

}

// ...

}We can define a helper method, nextStatusCondition, that updates the status condition of a Scanner resource in Kubernetes. It determines the status (True or False) based on the provided reason, defaulting to False unless the reason is Reconciled. It uses meta.SetStatusCondition to update the "Ready" condition of the Scanner resource, checking if the condition actually changed. If the condition has changed, it calls r.Status().Update() to persist the updated status to the Kubernetes API; otherwise, it does nothing and returns nil. This ensures, that when we send the describe command, we get some feedback about the state of the resource.

// internal/controller/scanner_controller.go

func (r *ScannerReconciler) nextStatusCondition(

ctx context.Context,

scanner *scannerv1.Scanner,

reason scannerv1.StatusReason,

) error {

status := metav1.ConditionFalse

if reason == scannerv1.Reconciled {

status = metav1.ConditionTrue

}

changed := meta.SetStatusCondition(&scanner.Status.Conditions, metav1.Condition{

Type: "Ready",

Status: status,

Reason: string(reason),

})

if !changed {

return nil

}

return r.Status().Update(ctx, scanner)

}After getting the scanResult data from database, we iterate over scanResults to collect the ImageID values into a slice called scannedImageIDs. Then, it creates a label requirement to exclude pods with the specified IgnoreLabel set to "true", logging an error and marking the Scanner resource as Failed if the requirement creation fails. Next, it retrieves a list of pods from the same namespace as the Scanner resource, applying the label selector created earlier to filter them. If the pod listing fails, the code logs the error and updates the Scanner resource's status to reflect the failure, ensuring proper status handling and resource reconciliation.

// internal/controller/scanner_controller.go:Reconcile()

// ...

scannedImageIDs := []string{}

for _, scanResult := range scanResults {

scannedImageIDs = append(scannedImageIDs, scanResult.ImageID)

}

labelRequirement, err := labels.NewRequirement(scanner.Spec.IgnoreLabel, selection.NotEquals, []string{"true"})

if err != nil {

reconcilerLog.Error(err, "failed to get IgnoreLabel requirement")

return ctrl.Result{}, r.nextStatusCondition(ctx, scanner, scannerv1.Failed)

}

podList := &corev1.PodList{}

if err := r.List(ctx, podList, &client.ListOptions{

Namespace: scanner.Namespace,

LabelSelector: labels.NewSelector().Add(*labelRequirement),

}); err != nil {

reconcilerLog.Error(err, "failed to list pods")

return ctrl.Result{}, r.nextStatusCondition(ctx, scanner, scannerv1.Failed)

}

// ...The next snippet identifies an unscanned container image by iterating through the pods and their container statuses, comparing the ImageID to the previously scanned image IDs. If an unscanned ImageID is found, it exits both loops early using the labeled OuterLoop. If all container images have already been scanned (imageID == ""), it logs a success message, updates the status of the Scanner resource to Reconciled, and schedules the next reconciliation after 10 seconds. The reconciler runs on a single thread by default, so requests are processed sequentially, avoiding race conditions and ensuring consistency during reconciliation. This design guarantees that only one reconciliation loop modifies a specific resource at a time.

// internal/controller/scanner_controller.go:Reconcile()

// ...

imageID := ""

OuterLoop:

for _, pod := range podList.Items {

// TODO: Handle init containers as well

for _, containerStatus := range pod.Status.ContainerStatuses {

if !slices.Contains(scannedImageIDs, containerStatus.ImageID) {

imageID = containerStatus.ImageID

break OuterLoop

}

}

}

if imageID == "" {

reconcilerLog.Info("all images scanned, successfully reconciled")

return ctrl.Result{RequeueAfter: 10 * time.Second}, r.nextStatusCondition(ctx, scanner, scannerv1.Reconciled)

}

// ...Then if listing the jobs fails, the reconciler logs the error and updates the Scanner status to Failed. It then iterates through the Jobs, checking if any of them have not yet succeeded (job.Status.Succeeded == 0), indicating that the Job is still in progress. If such a Job is found, it logs a message and updates the Scanner status to "Waiting", then returns.

// internal/controller/scanner_controller.go:Reconcile()

// ...

jobList := &batchv1.JobList{}

if err := r.List(ctx, jobList, &client.ListOptions{

Namespace: scanner.Namespace,

}); err != nil {

reconcilerLog.Error(err, "failed to list jobs")

return ctrl.Result{}, r.nextStatusCondition(ctx, scanner, scannerv1.Failed)

}

for _, job := range jobList.Items {

if job.Status.Succeeded == 0 {

reconcilerLog.Info("job is still in progress")

return ctrl.Result{}, r.nextStatusCondition(ctx, scanner, scannerv1.Waiting)

}

}

// ...After that it calls JobObjectService.Create() to generate a Job object for the given imageID in the specified namespace and logs an error if Job creation fails, updating the Scanner status to "Failed". The controller then sets the Scanner resource as the owner of the job using SetControllerReference, ensuring the job is garbage-collected when the Scanner resource is deleted. If the job creation in the cluster fails, it logs the error and updates the Scanner status to "Failed". On successful Job creation, it logs a success message and updates the Scanner status to "Scanning", marking the start of the image scanning process.

// internal/controller/scanner_controller.go:Reconcile()

// ...

nextJob, err := r.JobObjectService.Create(imageID, scanner.Namespace)

if err != nil {

reconcilerLog.Error(err, "failed to create job from template")

return ctrl.Result{}, r.nextStatusCondition(ctx, scanner, scannerv1.Failed)

}

if err := ctrl.SetControllerReference(scanner, nextJob, r.Scheme); err != nil {

reconcilerLog.Error(err, "failed to set controller reference on job")

return ctrl.Result{}, r.nextStatusCondition(ctx, scanner, scannerv1.Failed)

}

if err := r.Create(ctx, nextJob); err != nil {

reconcilerLog.Error(err, "failed to create job")

return ctrl.Result{}, r.nextStatusCondition(ctx, scanner, scannerv1.Failed)

}

reconcilerLog.Info("new job created")

return ctrl.Result{}, r.nextStatusCondition(ctx, scanner, scannerv1.Scanning)The predicate.GenerationChangedPredicate{} allows a controller to ignore update events where the spec is unchanged, and only the metadata and/or status fields are changed. The controller is also configured to track Job resources it owns (Owns), ensuring it reconciles when their status changes. Furthermore, it watches Pod events and maps them to reconciliation requests for Scanner resources using a custom mapping function (mapPodsToRequests).

func (r *ScannerReconciler) SetupWithManager(mgr ctrl.Manager) error {

return ctrl.NewControllerManagedBy(mgr).

For(&scannerv1.Scanner{}, builder.WithPredicates(predicate.GenerationChangedPredicate{})).

Owns(&batchv1.Job{}).

Watches(&corev1.Pod{}, handler.EnqueueRequestsFromMapFunc(r.mapPodsToRequests)).

Complete(r)

}Along with the controller-manager setup, we also need to ensure that it has the required RBAC (role-based access control) rules to watch pods and manage its Jobs. These manifests can be generated by adding the following lines to the internal/controller/scanner_controller.go file.

// +kubebuilder:rbac:groups="",resources=pods,verbs=list;watch

// +kubebuilder:rbac:groups=batch,resources=jobs,verbs=list;watch;createmapPodsToRequests() maps pod events to reconcile requests. It lists all Scanner resources in the same namespace as the Pod, returning an empty slice if the list operation fails. If one or more Scanner resources are found, it creates a single reconciliation request for the first Scanner in the list, identified by its name and namespace. If no Scanner resources exist, it simply returns an empty slice, meaning no reconciliation is triggered.

func (r *ScannerReconciler) mapPodsToRequests(ctx context.Context, pod client.Object) []reconcile.Request {

scannerList := &scannerv1.ScannerList{}

if err := r.List(ctx, scannerList, &client.ListOptions{Namespace: pod.GetNamespace()}); err != nil {

return []reconcile.Request{}

}

if len(scannerList.Items) > 0 {

return []reconcile.Request{{NamespacedName: types.NamespacedName{

Name: scannerList.Items[0].Name,

Namespace: scannerList.Items[0].Namespace,

}}}

}

return []reconcile.Request{}

}Grype is started as an initContainer and once it has done scanning, the output is saved into a temporary shared volume that the next container, curl can access.

curl is a command-line tool used to transfer data to or from a server using various network protocols like HTTP, HTTPS, FTP, and more. It is widely used to send requests, retrieve responses, and test APIs or web endpoints. With its extensive options, curl can handle headers, authentication, cookies, and data payloads for GET, POST, PUT, DELETE, and other HTTP methods. Its simplicity and flexibility make it a favorite for developers and system administrators for debugging and automation. We will harness its capabilities to send the result of grype back to our api through the ApiServiceHostname

The internal/service/job.template.yaml is parsed as a go template so that certain paramaters like ScanName, Namespace can dynamically changed. Here we are making use of the ttlSecondsAfterFinished property of jobs. It specifies the time-to-live (TTL) for the resource after it completes execution. Once the Job finishes, Kubernetes waits for the defined TTL (in seconds) before automatically deleting the resource, helping to clean up old, unused jobs. This property is particularly useful for managing resource lifecycle and avoiding clutter in the cluster, but it must be enabled in the cluster settings as it is a feature gate. Using this takes the responsibility of deleting Jobs away from our operator, but we can still have a look at what went wrong during the specified time. Once the unsucessful Job is not present in the Namespace the Scanner operator schedule it again.

# internal/service/job.template.yaml

apiVersion: batch/v1

kind: Job

metadata:

name: { { .ScanName } }

namespace: { { .Namespace } }

spec:

ttlSecondsAfterFinished: 300

backoffLimit: 0

template:

spec:

initContainers:

- name: grype

image: anchore/grype:v0.83.0

env:

- name: GRYPE_DB_CACHE_DIR

value: /grype-db

args:

- { { .ImageID } }

- --output

- cyclonedx-json

- --file

- /shared/scan-result.json

volumeMounts:

- name: shared

mountPath: /shared

- name: grype-db

mountPath: /grype-db

containers:

- name: alpine

image: alpine/curl:8.10.0

command: ["sh", "-c"]

args:

- |

echo '{"imageId":"{{.ImageID}}","report":'"$(cat /shared/scan-result.json)"'}\n' > /shared/scan-result.json;

curl -X PUT -H 'Content-Type: application/json' -d @/shared/scan-result.json {{.ApiServiceHostname}}:8000/scan-results;

volumeMounts:

- name: shared

mountPath: /shared

restartPolicy: Never

volumes:

- name: shared

emptyDir: {}

- name: grype-db

hostPath:

path: /grype-dbKind can be configured to use a config file on startup that can change the parameters of the cluster. This is very handy, since this allows us to mount the grype database from our host system, so the scan jobs do not have to download it again and again and can use the cached version. After creating the new configuration we can run the kind create cluster --config kind-config.yaml command to apply this configuration.

# kind-config.yaml

kind: Cluster

apiVersion: kind.x-k8s.io/v1alpha4

nodes:

- role: control-plane

extraMounts:

- hostPath: /home/outis/.cache/grype/db

containerPath: /grype-dbThe server package contains the implementation of handlers and Server struct which fits the interface generated by oapi-codegen, thereby fitting the schema defined in internal/oapi/oapi_definition.yaml. The next snippet defines a NewServer function that initializes and returns a new Server instance for handling scan-related operations and broadcasting updates, so that it can notify clients real-time. It creates a broadcast channel for transmitting messages and a connections map to track active WebSocket connections and their respective channels. A goroutine is started to continuously listen for messages on broadcastCh and forward them to all connected clients by iterating through the connections map. The Server is returned with initialized fields, including a WebSocket upgrader, the provided scanService for business logic, and a mutex (mu) for thread-safe access to shared resources.

// internal/server/server.go

func NewServer(

scanService service.ScanServiceInterface,

logger logr.Logger,

) *Server {

broadcastCh := make(chan string)

connections := make(map[*websocket.Conn]chan string)

go func() {

for {

message := <-broadcastCh

for _, ch := range connections {

ch <- message

}

}

}()

return &Server{

upgrader: &websocket.Upgrader{},

scanService: scanService,

logger: logger,

broadcastCh: broadcastCh,

connections: connections,

mu: sync.Mutex{},

}

}Then the PutScanResults HTTP handler is used to receive the payload from the finished Job objects. It starts by observing the duration of the request using a deferred function call, which I will explain more in the next section. The body of the incoming request is decoded into an oapi.ScanResult object (which is generated from the OpenAPI definition), and if decoding fails, it logs the error and responds with a 400 Bad Request. The scan result is then processed through the UpsertScanResult() method of the scanService, and specific errors like InvalidCycloneDXBOM or general errors are handled with appropriate logging and error responses (400 Bad Request or 500 Internal Server Error). Upon successful processing, the handler broadcasts the ImageID of the scan result to the previously initialized channel for notifiying subscribed clients and logs this event. Finally, it responds with a 200 OK, including the newly upserted scan result in JSON format, and logs any errors that occur during the response encoding.

// internal/server/server.go

func (s *Server) PutScanResults(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

defer observeDuration("PUT", "/scan-results")()

oapiScanResult := oapi.ScanResult{}

if err := json.NewDecoder(r.Body).Decode(&oapiScanResult); err != nil {

s.logger.Error(err, "PutScanResults")

http.Error(w, "Bad Request", http.StatusBadRequest)

return

}

scanResult, err := s.scanService.UpsertScanResult(oapiScanResult.ImageId, string(oapiScanResult.Report))

if errors.Is(err, service.InvalidCycloneDXBOM) {

s.logger.Error(err, "PutScanResults")

http.Error(w, "Bad Request", http.StatusBadRequest)

return

} else if err != nil {

s.logger.Error(err, "PutScanResults")

http.Error(w, "Internal Server Error", http.StatusInternalServerError)

return

}

s.broadcastCh <- scanResult.ImageID

s.logger.Info("PutScanResults", "new imageId broadcasted", scanResult.ImageID)

res := oapi.ScanResult{

ImageId: scanResult.ImageID,

Report: json.RawMessage(scanResult.Report),

}

w.Header().Set("Content-Type", "application/json")

w.WriteHeader(http.StatusOK)

if err := json.NewEncoder(w).Encode(res); err != nil {

s.logger.Error(err, "PutScanResults")

}

}We implemened this PUT operation in an idempotent way, so that applying the same request multiple times has the same effect as applying it once. In a typical PUT request, the client provides the full representation of the resource to be created or updated, and the server updates or creates the resource accordingly. Regardless of how many times the same request is sent, the resource's state on the server remains consistent, without unintended side effects.

The GetSubscribe() handler establishes and manages WebSocket connections for clients subscribing to scan updates. It upgrades an HTTP connection to a WebSocket using s.upgrader.Upgrade(), and if the upgrade fails, it logs the error and exits. Once the WebSocket connection is established, it initializes a channel for sending messages to the client and safely adds it to the connections map while ensuring thread safety using a mutex (s.mu). The usage of mutex is necessary here in order to ensure that all connected clients receive all messages at all times, since handlers can run not just asynchronously, but parallel too. A goroutine listens to the channel and sends ImageID updates to the WebSocket client, logging errors if message transmission fails. The handler enters a loop to monitor incoming messages from the client, breaking the loop when the connection is closed or a CloseMessage is received. We rely on defer to close both the connection and the channel owned by the client. These few functions well illustrate how to setup, receive and broadcast messages using go's concurrency features.

// internal/server/server.go

func (s *Server) GetSubscribe(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

defer observeDuration("GET", "/subscribe")()

c, err := s.upgrader.Upgrade(w, r, nil)

if err != nil {

s.logger.Error(err, "GetSubscribe")

return

}

defer c.Close()

ch := make(chan string)

defer close(ch)

s.mu.Lock()

s.connections[c] = ch

s.mu.Unlock()

go func() {

for {

imageId, ok := <-ch

if !ok {

return

}

data := []byte("\"" + imageId + "\"")

if err := c.WriteMessage(websocket.TextMessage, data); err != nil {

s.logger.Error(err, "Websocket")

}

}

}()

for {

msgType, _, err := c.ReadMessage()

if err != nil {

break

}

if msgType == websocket.CloseMessage {

break

}

}

s.mu.Lock()

delete(s.connections, c)

s.mu.Unlock()

}Object-Relational Mappers (ORMs) are tools that simplify database interactions by mapping database tables to programming language objects (structs), reducing the need for manual SQL queries. They improve developer productivity by allowing database operations like creation, retrieval, modification and deletion (CRUD) to be performed using familiar object-oriented syntax, which abstracts away database-specific details. ORMs ensure code readability and maintainability by aligning database logic with the application's structure, reducing boilerplate code. They also provide features like schema migrations, query building, and relationship management, making them ideal for applications with complex data models. However, while convenient, ORMs may sacrifice performance for simplicity, so they're best suited for scenarios where productivity and rapid development are prioritized over raw database efficiency.

For simplicity, we can use the TEXT datatype which can store a near unlimited number of bytes and is available in postgres, mysql and sqlite too, so it is suitable to store manifests. ImageID is used to differentiate the ScanResult objects, so it is used as a primary key within the database. The Report column contains the full CycloneDX BOM output of grype as a JSON string. To register this database model and create the proper columns, we can issue the db.AutoMigrate(&ScanResult{}) command during the startup of our program.

// internal/database/model.go

type ScanResult struct {

ImageID string `gorm:"primarykey;type:TEXT"`

Report string `gorm:"not null;type:TEXT"`

}The next code snippet defines the UpsertScanResult method, which processes a scan report and stores or updates it in the database. It first decodes the provided report string into a cyclonedx.BOM object using a JSON decoder, validating that the report is in a proper CycloneDX BOM format. If decoding fails, the method returns an error indicating an invalid BOM. A ScanResult object is created with the given imageId and report, which is then upserted into the database using an ON CONFLICT clause to update existing records if a conflict occurs. If the database operation fails, the method returns an error detailing the issue. Upon success, the newly created or updated ScanResult is returned to the caller.

// internal/service/scan.go

func (s *ScanService) UpsertScanResult(imageId string, report string) (*database.ScanResult, error) {

bom := cyclonedx.BOM{}

reader := strings.NewReader(report)

decoder := cyclonedx.NewBOMDecoder(reader, cyclonedx.BOMFileFormatJSON)

if err := decoder.Decode(&bom); err != nil {

return nil, fmt.Errorf("%w: %w", InvalidCycloneDXBOM, err)

}

scanResult := database.ScanResult{

ImageID: imageId,

Report: report,

}

res := s.db.Clauses(clause.OnConflict{UpdateAll: true}).Create(&scanResult)

if res.Error != nil {

return nil, fmt.Errorf("error while inserting ScanResult: %w", res.Error)

}

return &scanResult, nil

}This methods is used in the PutScanResults() handler and is called by the curl pod when the Job is finished. With this explaind we reviewd the entire route that the report takes on the backend side of the stack from grype through curl into the handler and then the service.

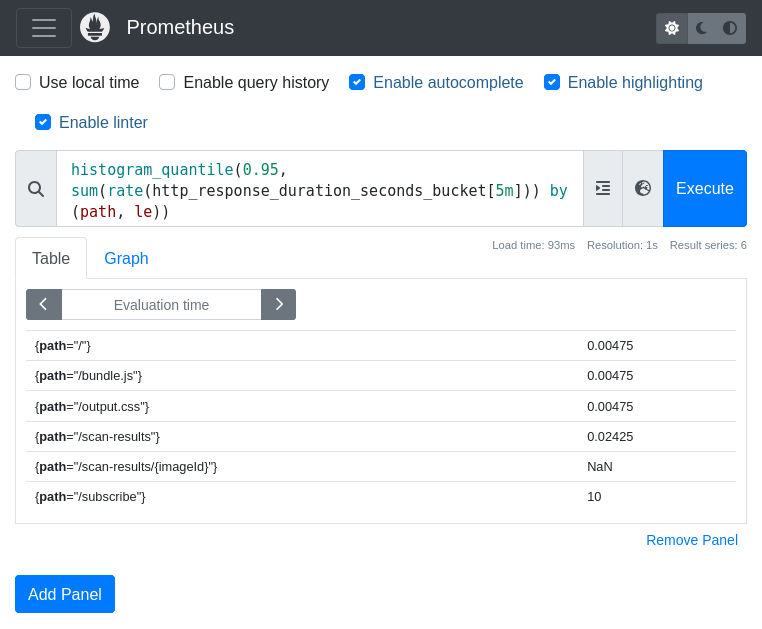

Prometheus is an open-source monitoring and alerting tool designed for collecting, storing, and querying metrics from various systems and applications. It uses a time-series database to store metrics data, allowing for analysis of trends and real-time monitoring. We can define a make command so installing kube-prometheus can be done automatically.

helm repo add prometheus-community https://prometheus-community.github.io/helm-charts

helm repo update.PHONY: setup-prometheus

setup-prometheus:

kubectl create namespace monitoring

helm install -n monitoring prometheus prometheus-community/kube-prometheus-stack

# kubectl port-forward service/prometheus-operated -n monitoring 9090:9090Prometheus scrapes metrics from target systems using HTTP endpoints, typically in a specific text-based format. It features a powerful query language called PromQL for data analysis and visualization, often integrated with dashboards like Grafana. Prometheus also includes built-in alerting capabilities, enabling users to define conditions and receive notifications when thresholds are breached.

Enabling Prometheus metrics is as easy as uncommenting the proper section in config/default/kustomization.yaml and also add a tag to the already defined ServiceMonitor resource so that Prometheus operator can register it. Of course after any modification involving the config directory we should regenerate the helm chart.

Kubernetes already has a metrics registry that we can add new items to using the MustRegster() method. The init() automatically runs when the package is imported, so it is a perfect place to register our new metric. We are defining a metric called http_response_duration_seconds which will be used to store how lon it took the server to respond to each method and path pair, which are called labels. Buckets are the histogram's predefined range of buckets for tracking durations, it divides a range of possible values into intervals, allowing the histogram to count how many observations fall into each interval.

var httpResponseDuration = prometheus.NewHistogramVec(

prometheus.HistogramOpts{

Name: "http_response_duration_seconds",

Help: "Duration of HTTP responses in seconds",

Buckets: prometheus.DefBuckets,

},

[]string{"path", "method"},

)

func init() {

metrics.Registry.MustRegister(httpResponseDuration)

}

func observeDuration(method, handlerPath string) func() {

start := time.Now()

return func() {

duration := time.Since(start).Seconds()

httpResponseDuration.WithLabelValues(handlerPath, method).Observe(duration)

}

}In Go, the defer statement schedules a function to be executed after the surrounding function completes, regardless of how it exits (like through a return or panic). Deferred calls are executed in last-in, first-out (LIFO) order, making them useful for cleanup tasks like closing resources. Putting the defer observeDuration("GET", "/subscribe")() as the first line of each http handler with the correct method and path ensures that the duration is always observed.

We can create a proper wrapper hook for the Subscriber class to make it work well within React components. A React hook is a special function that lets you use React features in functional components, like state and lifecycle methods. Preexisting hooks, such as useState and useEffect, simplify component logic and enable reusability of stateful behavior across components and are the building blocks that enable us to build more complex components. The convention is to start the name of such function with the 'use' word in order to signal other developers about its nature.

Our the useSubscriber hook is a modified version of the previously showed wrapper around the Subscriber class. It uses the Subscriber class to listen to events from a given URL ("/subscribe"). The hook accepts two callback props, onMessage and onConnection, which are called when respective "message" and "connection" events are triggered, passing along relevant data (e.detail) from each event. Inside the effect, once again an AbortController (ac) is created to allow cancelling and proper termination of the subscription when the component unmounts from the virtual DOM, by calling ac.abort() in the cleanup function. The onMessage and onConnection handlers are passed into the dependency list of useEffect, so that the hook is refreshed when the handlers change.

// frontend/src/hooks/useSubscriber.tsx

export function useSubscriber({ onMessage, onConnection }: UseSubscriberProps) {

useEffect(() => {

const ac = new AbortController();

const s = new Subscriber("/subscribe", { signal: ac.signal });

s.addEventListener("message", (e: CustomEventInit) => {

onMessage(e.detail as string);

});

s.addEventListener("connection", (e: CustomEventInit) => {

onConnection(e.detail as boolean);

});

return () => ac.abort();

}, [onMessage, onConnection]);

}With the help of createContext function we can implement a global state manager which holds and makes available the application's state and a dispatch function for state updates for other components. The GlobalStateProvider component employs the useReducer hook to manage the application's state using globalReducer, starting with initialState. Within this provider, two callback functions, onMessage and onConnection, handle specific events:

onMessagedispatches an "add" action to add a new item based on incoming messagesonConnectionfetches all scan result objects from the backend and dispatches a "connection_gained" with the payload when theSubscriberinstance transitions from offline to online state and a "connection_lost" action when the reverse happens. This way of operation ensures that when online all data shown on the UI is representing the current state of the cluster.

These two functions have to be defined using the useCallback hooks to cache them between rerenders, otherwise the Subscriber class would be detatched and re-attached repeatedly in an uncontrolled manner. useSubscriber hooks into these callbacks, and the provider component passes the context value, allowing child components to access and interact with the global state.

Here we have to use the encodeURIComponent() function in order to escape some special characters like forward slash and the at sign, since the imageId contains such characters.

// frontend/src/components/GlobalState.tsx

export const GlobalStateContext = createContext({

state: initialState,

dispatch: (action: Action) => {},

});

export type GlobalStateProviderProps = PropsWithChildren<{}>;

export const GlobalStateProvider = ({ children }: GlobalStateProviderProps) => {

const [state, dispatch] = useReducer(globalReducer, initialState);

const onMessage = useCallback(

async (imageId: string) => {

const res = await fetch(`/scan-results/${encodeURIComponent(imageId)}`);

if (!res.ok) {

return;

}

const scanResult = (await res.json()) as ScanResult;

dispatch({ type: "add", payload: scanResult });

},

[dispatch]

);

const onConnection = useCallback(

async (isConnected: boolean) => {

if (isConnected) {

const res = await fetch(`/scan-results`);

if (!res.ok) {

return;

}

const scanResults = (await res.json()) as ScanResult[];

dispatch({ type: "connection_gained", payload: scanResults });

} else {

dispatch({ type: "connection_lost" });

}

},

[dispatch]

);

useSubscriber({ onMessage, onConnection });

return (

<GlobalStateContext.Provider value={{ state, dispatch }}>

{children}

</GlobalStateContext.Provider>

);

};The initialState includes two properties: isConnected, a boolean for connection status, and scanResults, an array of scan results. The Action type defines four possible actions: "add" to add a new scan result, "remove" to delete a scan result by id, and "connection_gained" with a payload that contains all the currently available scan results and "connection_lost" to show that the subscriber does not have a live connection. The globalReducer function derives the next state based on the action type. This setup allows for flexible and predictable state management, supporting multiple actions that modify the global state in specific ways so the mutation logic is separated from visualization. The ScanResult type is imported from the oapi.gen.d.ts which was generated based upon the OpenAPI schema by openapi-typescript.

// frontend/src/components/GlobalState.tsx

const initialState = {

isConnected: false,

scanResults: [] as ScanResult[],

};

type State = typeof initialState;

type Action =

| { type: "add"; payload: ScanResult }

| { type: "remove"; payload: ScanResult["imageId"] }

| { type: "connection_gained"; payload: ScanResult[] }

| { type: "connection_lost" };

function globalReducer(state: State, action: Action): State {

switch (action.type) {

case "connection_lost": {

return { ...state, isConnected: false };

}

case "connection_gained": {

return {

...state,

isConnected: true,

scanResults: action.payload.sort((a, b) =>

a.imageId.localeCompare(b.imageId)

),

};

}

case "add": {

const index = state.scanResults.findIndex(

(item) => item.imageId === action.payload.imageId

);

let scanResults: ScanResult[] = [];

if (index !== -1) {