I want to express my gratitude to my outstanding teammates iafoss, vincentwang25, anjum48, and yamsam for their incredible contribution towards our final result. It was a great team effort, and the team brought the best from each of us. I am very glad that we got into the money (3rd place) and a gold medal for this competition.

The write-up is based on our posted solution(https://www.kaggle.com/c/g2net-gravitational-wave-detection/discussion/275617), which is the result of the cumulative efforts of all our team members. I modified it to make it more pedagogical and added several sections to include my experiences in the competition and some of my thoughts after the competition is over.

Gravitational waves (GW) are predicted by Einstein’s general theory of relativity. They are ripples in the fabric of space-time. Currently, we have 3 GW detectors (LIGO Hanford, LIGO Livingston, and Virgo) on the earth. GW can produce unimaginably tiny strains on the detectors. Even the detectors are some of the most sensitive instruments on the planet, the signals are buried in detector noise. Therefore, the data from the detectors are time series, mostly with very low signal to noise ratio(SNR).

(The series of images above were taken from the 2015 paper, Observation of Gravitational Waves from a Binary Black Hole Merger(https://journals.aps.org/prl/abstract/10.1103/PhysRevLett.116.061102), announcing the discovery of gravitational waves from a pair of merging black holes.)

One approach used by researchers to find the trace of GW signals is a computational method called matched-filtering. However, it requires to compare the time series data with a huge number of templates, for each data sample. This method is very computational demanding. To discover gravitational waves more efficiently and accurately, people use machine learning methods.

In this competition, people aim to detect GW signals from the mergers of binary black holes. Specifically, people build models to analyze simulated GW time-series data from a network of Earth-based detectors. The data are time series of 2-seconds(length 4096, with sampling rate 2048Hz) chunks containing simulated gravitational wave measurements from a network of 3 gravitational wave interferometers (LIGO Hanford, LIGO Livingston, and Virgo). Each time series contains either detector noise or detector noise plus a simulated gravitational wave signal. The task is to identify whether a GW signal is present in the data. The training set has 560k samples and the test set has 226k samples. The SNR is generally low, and in some cases almost undetectable. The metrics for this competition is area under the ROC curve between the predicted probability and the observed target.

Below we show a few examples of GW time-series data. The first figure is not based on the competition data, but it's the raw wave for GW150914(first detected GW, with very high SNR) from one of the detectors. The second figure is the processed wave for GW150914 from two of the detectors, using whitening and bandpassing. You can see a clear signal around 0.42 second(because the SNR is high). The third figure is an example wave from the competition dataset. In general, one cannot see signals with naked eyes for most of the data, even after preprocessing.

(It should be noted that all the number estimations for improvement of the model(boost) from the methods mentioned below in this report depend on when the methods are applied. Models are harder to improve when their scores are higher, because the mistakenly classified samples are usually lower SNR samples. 1bps=0.0001, a term borrowed from finance industry.)

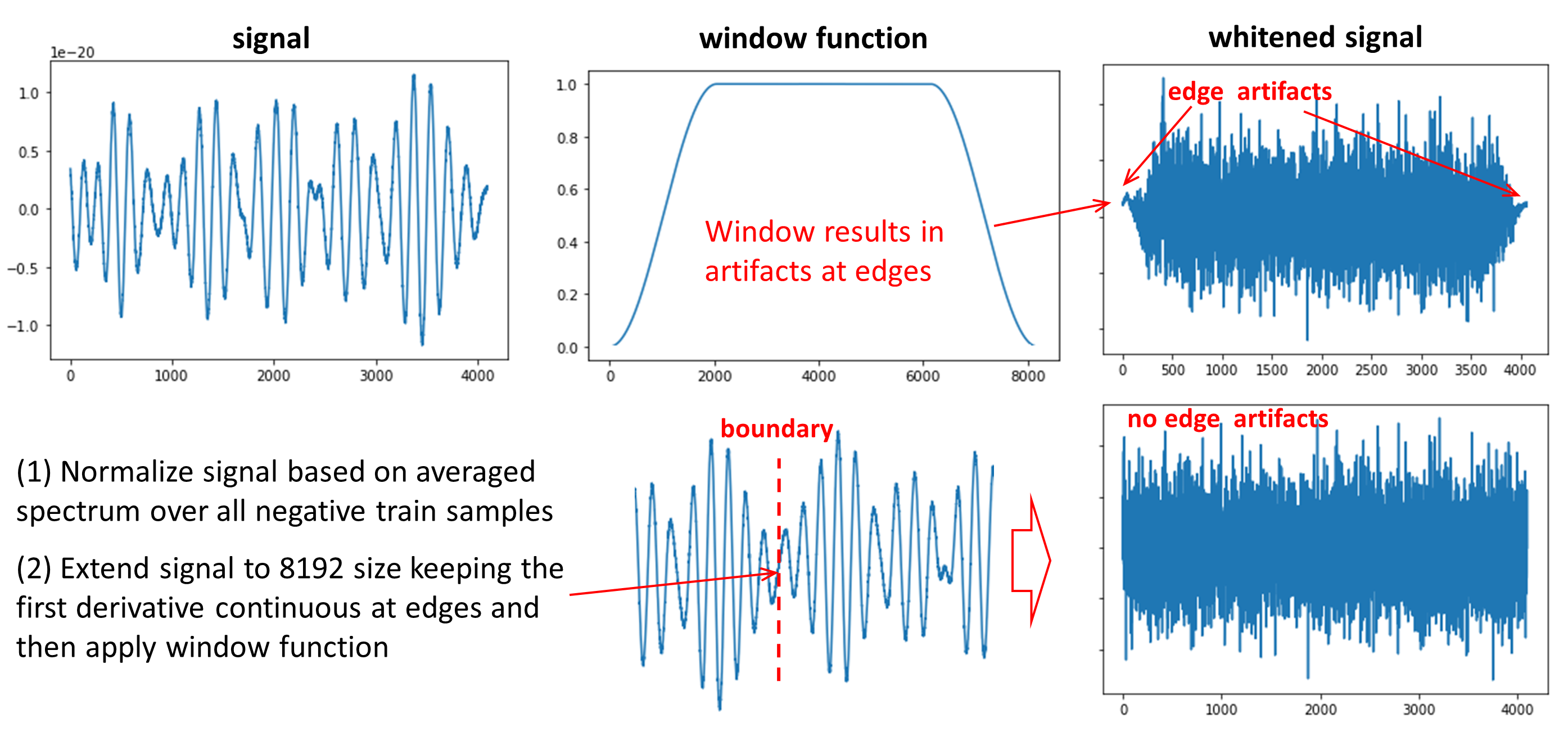

- Perform whitening to normalize power of signals from different frequencies (essential for 1D models and big boost for 2D models)

- Use average power spectral density (PSD) of noise sample data for PSD estimation (crucial for whitening)

- Extend waves to reduce artifacts near the boundary

- Whiten signals with estimated PSD and Tukey window as window function

- Customized network architecture (CNN) targeted at GW detection

- Data augmentation and test-time augmentation (TTA): vertical flip, shuffle LIGO channels, Gaussian noise, time shift, time mask, Monte Carlo dropout

- CQT, CWT Transformation from 1D time series to 2D spectrograms

- EfficientNet, ResNeXt, InceptionV3 etc.

- Data augmentation and TTA: shuffle LIGO channel

- 5 folds stratified cross validation

- Pretraining with simulated GW

- Using Pseudo Labels for training

- Using binary cross entropy loss for training

- Post-training with rank loss

- Using AdamW, RangerLars+Lookahead optimizer

- Cosine annealing learning rate scheduler with warmup

- 15 1D Models + 8 2D Models in our submissions

- Weight optimization/polynomial features, with Covariance matrix adaptation evolution strategy (CMA-ES) optimizer.

Regarding whitening, direct use of packages, such as pycbc(which is the "official" package for LIGO/Virgo), doesn’t work mainly because of the short duration of the provided signals: only 2 seconds chunks in contrast to the almost unlimited length of data from LIGO/Virgo detectors. To make the estimated PSD smooth, pycbc package uses an algorithm that corrupts the boundary of data, which is too costly for our dataset, whose duration of signals is only 2 seconds. We reduce the variance of estimated PSD by taking the average PSD for all negative training samples. This is the key to make whitening work (interestingly, this averaging idea came up independently by me and my teammate Anjum before our team merging).

This figure below shows the estimated PSD in log-log scale. Notice that the power densities of lower frequency is much higher than those of higher frequency, and also the two PSD curves from LIGO detectors are overlapping(in orange).

To further reduce the boundary effect from discontinuity and allow ourselves to use a window function that has a larger decay area (for example, Tukey window with a larger alpha), we first extend the wave while keeping the first derivative continuous at boundaries. Finally, we apply the window function to each data and use the average PSD to normalize the wave for different frequencies.

Steps:

- Extend the signals to 4 seconds

- Obtain smooth PSD, by averaging estimated PSD of all negative training examples

- Apply Tukey window with alpha(controlling the size of the decay window) 0.5

- Whiten signals with smooth PSD

1D models appeared to be the key component of our solution, even if we didn't make great improvement until the last 1.5 weeks of the competition. The reason why these models were not widely explored by most of the participants may be the need of using signal whitening to reach a performance comparable with 2D models (at least easily), and whitening is not straightforward for 2s long signals (see discussion below). However, 1D models are much faster to train, and they also outperform our 2D models. The performance of our best single 1D model is 0.8819/0.8827/0.8820 at CV, public, and private LB. It can reach top-7 LB after about 8 hours of training on our workstations.

Network architecture

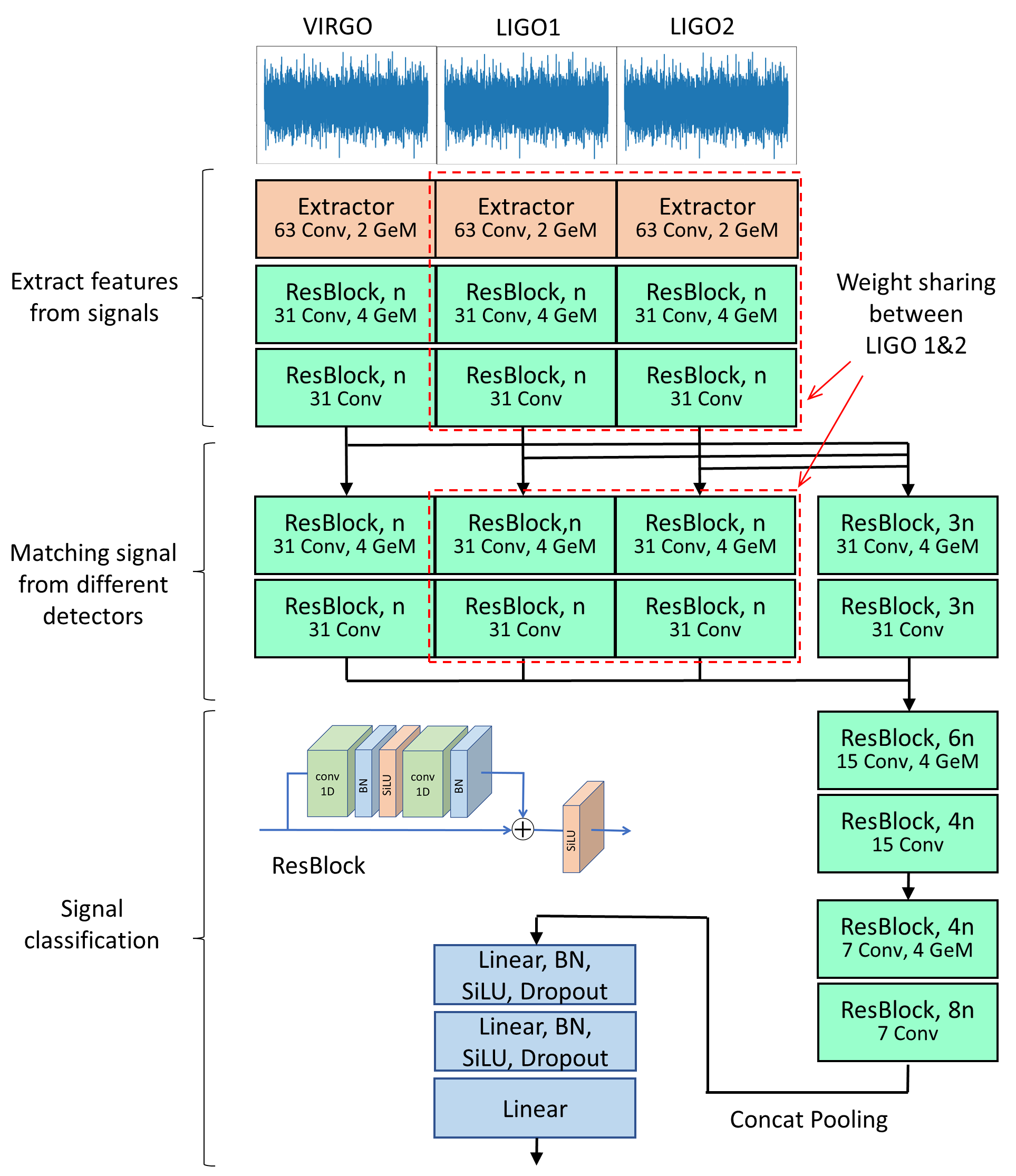

One of the main contributions towards this result is the design of the network architecture for GW detection task. Specifically, GW is not just a signal of the specific shape, but rather a correlation in signal between multiple detectors. Meanwhile, signals may be shifted by up to ~10-30 ms because of the time needed for the signal to cross the distance between detectors. So direct concatenation of signals into (3,4096) stack and then applying a joined convolution is not a good idea (our baseline V0 architecture with CV of 0.8768). Random shift between components prohibits the generation of joined features. Thus, we asked the question, why not split the network into branches for different detectors, like proposed in this paper? So the first layers, extractor and following Res blocks, learn how to extract features from a signal, a kind of learnable FFT or wavelet transform. So before merging the signals the network already has a basic understanding of what is going on. We also share weights between LIGO1 and LIGO2 branches because the signals are very similar.

Merge of the extracted features instead of the original signal mitigates the effect of the relative shift (like in Short Time Fourier Transform correlation turns into a product of two aligned cells). So simple concatenation at this stage (instead of early concatenation) followed by several Res blocks (V1 architecture) gives an improvement of 20bps. However, the model after combining the signal and getting a better idea about GW, may still want to look into individual branches as a reference. So we extend our individual branches and perform the second concatenation at the next convolutional block (V2 architecture). After the basic structure of the V2 model was defined, we performed several additional experiments for further model optimization. The model architecture tricks giving further improvement include the use of SiLU instead of ReLU, use of GeM instead of strided convolution, use of concatenation pooling at the end of the convolutional part. In one of our final runs, we used ResNeSt blocks (Split Attention convolution) having a comparable performance in the preliminary experiments, but it also performed slightly worse at the end of full training. Using CBAM modules and Stochastic Depth modules gave a slight boost and made the 1D models more diversified. The network width, n, is equal to 16 or 32 for our final models. One of our experiments is also performed for a combined 1D+2D models, pretrained separately and then finetuned jointly, which gave 0.8815/0.8831/0.8817 score.

Data augmentation and test-time augmentation (TTA)

Augmentation is very effective for 1D CNN models, compared to 2D models. We used vertical flip, shuffle LIGO channels, Gaussian noise, time shift, time mask and Monte Carlo dropout. Data augmentation and TTA gives a big boost. A rough estimation would be 25~45 bps. We noticed that augmentations that were too aggressive hurts the performance of the model. Also, the boost from augmentation plateaus when adding more augmentations on top of others.

Training procedure for 1D models

- Pretraining with Simulated GW for 2 ~ 4 epochs (2 ~ 8bps boost)

- Training for 4 ~ 6 epochs

- Training with rank loss and low learning rate for 2 epochs (~1bps performance boost)

Things that didn’t work for 1D models

larger network depth (extra ResBlocks), smaller/larger conv size in the extractor/first blocks, multi-head self-attention blocks before pooling or in the last stages of ResBlocks (i.e. Bottleneck Transformers), densely connected or ResNeXt blocks instead of ReBlocks, learnable CWT like extractors (FFT->multiplication by learnable weights->iFFT), WaveNet like network structures, pretrained ViT following the extractors (instead of customized ResNet).

Among the various preprocessing approaches we tried, we found that whitening, which we discussed earlier, was the most effective preprocessing for signals. We performed Constant Q transformation (CQT) or Continuous Wave Transformation (CWT) on the whitened time series data. Then we created 2D models for these spectrograms/scalograms. We tried various augmentations for 2D images (mixup, cutout, …), but most of them did not work here, however mixup on the input waveform prior to CQT/CWT did help counteract overfitting. The most effective one was the augmentation of swapping LIGO signals. This worked both for training and inference (TTA, Test Time Augmentation). The performance of our best single 2D model is 0.8787/0.8805/0.8787 at CV, public, and private LB.

We show here two examples of spectrograms with GW in it(one easy to identify, with high SNR, another hard to classify correctly, with low SNR) after applying CQT on the time series.

Here are some more details:

- CQT and CWT spectrogram/scalogram generated based on the whitened signal

- CQT parameters: CQT1992v2(sr=2048, fmin=20, fmax=1000, window='flattop', bins_per_octave=48, filter_scale=0.25, hop_length=8)

- Resize the images (128x128, 256x256, 512x512)

- CNN models: EfficientNet(B3, B4, B5, B7), EfficientNetV2(M), ResNet200D, Inception-V3 (also we performed a number of initial experiments with ResNeXt models)

- Soft leak-free pseudo labeling from ensemble results

- LIGO channel swap argumentation (randomly swapping LIGO channels) for both training and TTA

- 1D mixup augmentation prior to CQT/CWT

- Adding a 4th channel to the spectrogram/scalogram input which is just a linear gradient (-1, 1) along the frequency dimension used for frequency encoding (similar to positional encoding in transformers)

We use 5 folds stratified cross validation. For training, we use binary cross entropy loss function, AdamW and RangerLars+Lookahead optimizer and cosine annealing learning rate scheduler with warmup. There are other important aspects related to training elaborated below.

Pretraining with self-synthetic GW data

This idea is coming from curriculum learning, and in this paper, it mentioned that “We find that the deep learning algorithms can generalize low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) signals to high SNR ones but not vice versa”. So we synthesize data GW signals and inject them into the noise, giving low SNR. We tried to find a distribution of 15 GW parameters that is similar to competition data. Even though there are 15 parameters, we found that the most important one is the total mass and mass ratio (maybe we are wrong) because it affects the shape of GW the most through eyeballing. So we adjust the total mass and mass ratio using different distributions and inject the signal into the noise with a given SNR following max(Gaussian(3.6,1),1) distribution. This SNR distribution is determined by checking the training loss trend: we want it to follow the trend of original data (not too hard, not too simple). Pretraining with our synthetic data helps the performance (2~8bps). We also tried to follow this idea of giving difficult positive samples from the train data more weight, but we didn’t make it work due to time constraints.

Pseudo Labels

We assign labels to test data based on a prediction from an earlier model and then we use test data together with train data on a new model. It gave a big boost to our models. Here are some important points for Pseudo-Labelling (PL):

- PL should be leak free to ensure reliable cross validation. Don’t mix models trained on different folds to generate PL.

- Soft PL(probabilities between 0 and 1) works better than hard PL (0 and 1 targets).

- Using progressive PL(PL from the most updated model everytime) helps model performance. For example, our best single model with 0.8820 private LB can improve to 0.8824 private LB by using PL from our best models, which can make to rank No. 5 by itself.

Rank Loss

- Invented by iafoss in a previous competition. This is a loss function that aims to rank samples correctly.

- Rank loss is similar to a loss function such as ROC-star, which is a loss function designed to maximize the ROC-AUC score and to facilitate optimization, while avoiding discontinuities such as those in ROC-AUC metric.

- Post-train with rank loss gives ~1bps performance boost

First, to confirm that train and test data are similar and do not have any hidden peculiarities, we used adversarial validation and found that it gave 0.50 AUC score, implying that train and test data are indistinguishable.

We tried many different methods to ensemble the models and saw the following trend for their performance: Weight optimization > Neural Network > other methods. For weight optimization, using covariance matrix adaptation evolution strategy optimizer(CMA-ES) is better than using Scipy optimizers, and using logits(log-odds) is better than using rank of probabilities or probabilities themselves.

For our first submission, we generate degree-2 polynomial features from model predictions with sklearn.preprocessing.PolynomialFeatures and then use CME-ES optimizer for optimization. It brings the highest CV but it comes with a small chance of overfitting. We tested it on the public LB. The score is good and we think it's not showing signs of overfitting. We were glad that it turned out to be our best submission(private LB 0.8829).

Our second submission combines weight optimization, bootstrapping and mimicing private LB data. We do this for two reasons:

- We found the CV and public LB correlation is very high. We also used adversarial validation to check that indeed training and testing data are similar. By mimicing private LB in training data, models can potentially get a better performance at the private LB.

- Boostrapping data and averaging the obtained weights makes the produced model weights more robust against the data noise.

We mimicked the private LB data by excluding 16% (which is the percentage of public LB data among all the test data) of our OOF data which has a similar score to our public LB score, and optimized weights for models on the remaining data and then performed averaging for the obtained weights. The CV score turned out to match the private LB score exactly(0.8828).

In this competition, I mostly worked on pipeline building/optimization, signal whitening, 1D models, data augmentation/TTA, Pseudo-Labelling, and model ensemble (scipy optimize method for weight optimization). My teammates and I think the most important things in our models are preprocessing(whitening) and 1D networks, and I am proud to say that I contributed a lot to these areas.

I started this competition working alone. The first things I did was to read all the discussion and all relevant papers related to GW and CNN published by physicists. Almost all people on the discussion forum talked about CQT and 2D CNN models, while some of the papers I read claim that 1D CNN on time series performs better than 2D CNN on spectrograms.

After understanding one of the most voted published kernel/code by Nakama and modified it so that the code runs very efficiently, I decided to focus on the approach of 1D CNN models for the following reasons: (1) the majority of related published papers use 1D CNN directly on the time series; converting to a spectrogram may be a too strong prior and causing to lose important information in the time series (2) I think 1D models will be very different from 2D models and it will make a great ensemble and good for later team merging. At the beginning, I couldn’t make 1D model work (AUC around 0.500) because I didn’t do whitening as preprocessing. After I successfully found out the creative way to estimate PSD and perform whitening preprocessing, the AUC scores are finally no longer 0.500. I tested the whitening on 2D CNN models, and it also gives a big boost (~30 bps). I continued to improve 1D models by designing better network architectures and discovering useful augmentations.

After this stage(about one month), I realized that I need to learn from others and team up to get better results. So I teamed up with Vincent. He focused on 2D models and I continued to work on 1D models. The ensemble of 1D model and 2D model was indeed very useful as expected and we got to silver zone. We were aiming for the gold medal and therefore thought we should enlarge our team. We formed a five-men team when there were two and a half weeks left. During the last 1.5 weeks, I got a lot of help on 1D models from iafoss, who is very experienced in CNN (and promoted to competition grand master from the gold medal of this competition) and came up with the brilliant idea of separating the three channels at first and then merging later. We improved the 1D model together and the model performance increased greatly.

Some of the most important lessons I learned:

- Find the balance between thinking and doing. Sometimes one needs to experiment 10 ideas to find one that works. Sometimes thinking can lead to an approach that can’t be found by experiments.

- Focus on the most important things. For example, I focused on 1D model from the very beginning and sticked with it until the end of competition. Even if I knew this was the right approach I should follow, it still took a lot of effort to not abandon it or be distracted, because it was very hard to make 1D models work as well as (or better than, as it turns out) 2D models, and few teams were working on 1D models.

- We should’ve spent more time on synthesizing data. It was the main reason the 1st place is so far ahead of others. We guessed that 1st place was so far ahead amid the competition because they use synthetic data, but we didn’t spend enough time on it. The boost from our synthetic data is too little. It could lead us to win the 1st place if we make it work better.

- It’s better to change only one thing at a time in the model, so that one can track what works.

- Computation resources are important. Fast iteration is important. One way is to use smaller model or less data.

- Strategies of teaming up are important and great teammates are more than crucial(unless you want a solo gold).

- Hardworking pays off.

As a winner and required by the competition, we open sourced our codes. It can be found here: https://github.com/richardxing/G2Net_GoGoGo