Project to replicate manual steering behaviour when driving a car

The goals of this project are as follows.

- Use the Udacity Unity simulator to collect data of good driving behaviour

- Build a convolutional neural network in Keras that predicts steering angles from in-simulation camera images

- Train and validate the model with a suitably curated and augmented training and validation set

- Test that the model successfully drives round Track 1 without leaving the road

- Present some observations, lessons learnt and conclusions

In this section the rubric points for this project are considered individually so as to address the notable aspects of my particular implementation and training strategy.

This project includes the following files.

- model.py containing the script to create and train the model

- drive.py for driving the car in autonomous mode

- bespokeLoss.py, which defines a bespoke exponentially weighted loss function to help with steering more assertively round bends

- model.h5 containing a trained convolution neural network

- README.md summarising the results

- model_weights.h5 containing just the weights from the trained network above (useful for running the training script

model.py)

Using the Udacity provided simulator and the linked drive.py file, the car can be driven autonomously round the track by executing the following command in a terminal.

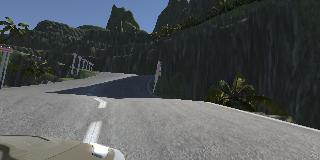

python drive.py ./output/model.h5Below is a preview of the simulation video capture; the full video is available here.

The model.py file contains the code for training and saving the convolutional neural network. The file shows the pipeline used for training and validating the model, and it contains comments to explain how the code works.

The code describing the CNN architecture can be found within the instantiate_model(learningRate) function in lines 28 -- 57 of the model.py file.

As can be seen from the summary printout in the next section, this model contains dropout layers in order to reduce overfitting, each with drop probability 0.25 and 0.5, respectively.

The model was trained and validated on different data sets to ensure that the model was not overfitting. The model was tested by running it through the simulator and ensuring that the vehicle could stay on the track.

The model uses an Adam optimiser. The learning rate proved to be a critical parameter to ensure the eventual success of the autonomously driven laps. Whilst values of 0.01 and 0.001 yielded promising and partially successful results, I eventually settled on 0.00001 as being the best choice.

Training data were chosen to keep the vehicle driving on the road. Fortunately Udacity had already provided a handy training set which included several sections of recovery driving, in addition to normal laps.

Furthermore, in order to reduce overfitting on a single track and to help the model generalise better, I also augmented Track 2 driving data to the overall training and validation set -- more details on the training strategy are provided in the next section.

Fairly early on in the project, I settled upon the well known End to End Learning for Self-Driving Cars paper as the basis for my model architecture, after making slight modifications to accommodate the image resolution, aspect ratio and certain specifics relating to my overall training strategy for this project.

At the end of the process, the vehicle is able to drive autonomously round the track without leaving the road.

The final model architecture is summarised in the table below.

_________________________________________________________________

Layer (type) Output Shape Param #

=================================================================

cropping2d_1 (Cropping2D) (None, 90, 320, 3) 0

_________________________________________________________________

average_pooling2d_1 (Average (None, 45, 160, 3) 0

_________________________________________________________________

lambda_1 (Lambda) (None, 45, 160, 3) 0

_________________________________________________________________

conv2d_1 (Conv2D) (None, 41, 156, 24) 1824

_________________________________________________________________

conv2d_2 (Conv2D) (None, 37, 152, 36) 21636

_________________________________________________________________

conv2d_3 (Conv2D) (None, 33, 148, 48) 43248

_________________________________________________________________

conv2d_4 (Conv2D) (None, 31, 146, 64) 27712

_________________________________________________________________

conv2d_5 (Conv2D) (None, 29, 144, 64) 36928

_________________________________________________________________

flatten_1 (Flatten) (None, 267264) 0

_________________________________________________________________

dropout_1 (Dropout) (None, 267264) 0

_________________________________________________________________

dense_1 (Dense) (None, 100) 26726500

_________________________________________________________________

dropout_2 (Dropout) (None, 100) 0

_________________________________________________________________

dense_2 (Dense) (None, 50) 5050

_________________________________________________________________

dense_3 (Dense) (None, 10) 510

_________________________________________________________________

dense_4 (Dense) (None, 1) 11

=================================================================

Total params: 26,863,419

Trainable params: 26,863,419

Non-trainable params: 0

_________________________________________________________________

Shown below is a visualisation of the architecture (note: the layer dimensions are depicted in accordance with a logarithmic scale).

It became apparent early on that capturing multiple laps with the correct or proper driving form was not going to be sufficient. There are manifold reasons for this, and hence the following measures were taken to ensure proper training of the model.

- In order to help the model focus only on the most critical part of the image, the raw input was immediately cropped to only show the track and a small part of the horizon in the input stage; this is illustrated in the images below.

- Inherent in the training process is the assumption that a snapshot of the track with its associated steering angle data corresponds to a specific instant in time -- whilst undoubtedly true, this fact poses problems when attempting to replicate this by running the model in autonomous mode. The crux of the problem is that even on a powerful and capable machine, there is inevitably some lag time between each of the steps pertaining to image processing, steering angle prediction and actual execution of the requested steering input. Consequently, the model is perpetually behind where it needs to be, and the overall setup does not allow for perfect replication of its predictions.

- Primarily staying near the centre of the track during the data collection phase would mean that the model is given little to no information on how to recover when it is too far off-centre and dangerously close to veering off-track.

- The lack of any explicit information or training on the dynamics of driving -- or, for that matter, on how to detect the road curvature up ahead -- means that without the correct training strategy predicated on a carefully curated data set, it would be very difficult to teach the model any recovery tactics to help it perform course corrections, let alone imbuing it with anticipatory behaviour.

- The three preceding points notwithstanding, there are certain techniques which could be adopted in addition to simply growing the share of images depicting how to properly negotiate curves, and to get back on track if the model begins to drift off course. One measure that was incorporated was to change the loss metric from the mean squared error to one which is weighted exponentially in terms of the magnitude of the true steering angle in the original training run -- in other words, by placing the square of the training angle as the main argument in the exponential envelope, we are essentially telling the model during training that veering off-course whilst driving along a curved section incurs a significantly greater penalty than drifting on a straight stretch. This bespoke loss function is defined in the file bespokeLoss.py included in this project, and this function is called in lines 55 and 130 of

model.pyand the modifieddrive.py, respectively. - The fifth point above can significantly ease the burden on the data collection exercise by placing the emphasis back on primarily collecting examples of driving the right way -- consequently, in the light of a suitable choice of loss function, training a neural network to drive is not so different from teaching a human how to drive properly and safely, after all.

- As can be seen from the model architecture summary table above, two dropout layers were introduced in-between the dense layers, with drop probabilities of 0.25 and 0.5, respectively. This helped combat over-fitting to the data corresponding to any single track.

- Moreover, the data sets were augmented in two ways. First, images were added from the left and right camera views in addition to the centre camera, and synthetic steering values corresponding to each left and right image were augmented to the nominal steering data corresponding to the centre images. An example set of screenshots is shown below.

Next, every image was also mirrored left-to-right to simulate driving in the opposite direction -- of course, this meant that the steering angles also had to be negated. The flipped images were in addition to raw data collected whilst driving the "wrong way" along the track, as it were.

- Last but not least, to further combat overfitting and help the model generalise better, the training and validation sets were augmented with driving data from two additional tracks (the old stable release of the simulator has a different Track 2 than the beta version).

As per usual practice, the augmented data were split into 80 % training and 20 % validation sets, respectively, and they were shuffled randomly prior to creating the batches.

This was an exceptionally challenging project, and required the utilisation of many tricks and techniques to finally yield a model and associated training regimen that resulted in a successful lap round Track 1 in autonomous mode. Some of the keys to my personal success in this project are collected here in case others find them useful.

Data collection: perhaps one of the most surprising revelations was the best input device for driving the car manually. For driving along Track 1 in the beta simulator, my recommendation is to pick a device in the following order of preference.

- touchpad

- mouse

- joystick or gamepad such as the Wii U Pro controller

For Track 2, on the other hand, which contains many tight bends, the best choice in my opinion is to use the mouse (option #2 above) whilst periodically easing off the throttle to allow for easier steering.

Lastly, in the case of the original, older version of the simulator, a joystick is perhaps the best choice -- I was not able to configure a mouse or touchpad to steer in that version.

Model architecture: the biggest surprise here was the fact that a few convolutional and dense layers were sufficient to get the job done, without the need for any esoteric activation functions or nonlinearities.

Training strategy: I had some trouble creating my own recovery data for the additional tracks, so I opted instead to improve the training process itself by guiding the model to steer more assertively when going round bends -- this was achieved by introducing an exponentially weighted loss function which grew in accordance with the exponential of the square of the steering angle. This did not eliminate the need for recovery example data by any means, but certainly helped obviate the need to skew the data more towards sections that had lots of curves -- in the case of track 1, this would have necessitated discarding a lot of perfectly good data.

Equipment and setup: I personally recommend driving in autonomous mode on a local machine equipped with a GPU rather than on the workspace, in order to minimise lag times. Unfortunately even a small amount of processing lag can have a noticeable destabilising effect in many scenarios during autonomous driving mode, since the model is just not very robust even after many epochs of training with all of the varied data collecting and augmenting methods described previously.

I have every intention of revisiting this project in the very near future. The first order of business is to augment more track 2 driving and recovery data and attempt to help the model complete this track successfully.

Look-ahead parameter: another major topic is exploring options to address the time lags occurring in the processing and execution steps. To this end, during training, instead of feeding the current steering angle, it might be a better idea to look a bit further ahead by a few frames, in anticipation of the ever existent (but likely nonuniform) processing lag. Hence, by implementing a tuneable look-ahead parameter to advance the steering angle labels by a fixed number of frames, it might be possible to improve the model's performance by helping it steer more proactively and stay close to the centre of the path at all times.

I also see numerous opportunities for refinement, ranging from architecture tweaks, exploring the right choices for critical hyperparameters, all the way down to the specifics of identifying the best kind of raw data and augmentation strategies, not to mention the best loss functions and optimisers based on the application or task / goal at hand.