The Terminal Universal Password Manager (tupm) is a terminal-based

interface to password manager databases produced by the

Universal Password Manager (UPM) project.

This is a proof-of-concept exercise, and should not be used in

production to protect real secrets.

Important disclaimers:

- This program may not be secure or reliable. It may corrupt your password database, expose your secrets, and keep your cereal from staying crunchy in milk. You should absolutely read the "Risks" section, below, before even thinking about using it. Consider yourself warned.

- This code is an independent re-implementation of UPM, and is not related to the original UPM program or its author in any way other than its ability to read and write UPM databases and speak the HTTP-based UPM sync protocol.

- This program was written as a learning exercise to gain experience with the process of developing Rust crates from "hello world" to "cargo publish". The contained library providing access to UPM databases may be of some use for developers looking to import and export, but the program as a whole should be considered more of a proof-of-concept rather than production-ready software.

Tupm is dual-licensed under MIT or Apache 2.0, the same as Rust itself.

Tupm may be downloaded and installed via the Rust cargo command:

$ cargo install tupm

Terminal Universal Password Manager 0.1.0

Provides a terminal interface to Universal Password Manager (UPM) databases.

USAGE:

tupm [FLAGS] [OPTIONS]

FLAGS:

-e, --export Export database to a flat text file.

-h, --help Prints help information

-p, --password Prompt for a password.

-V, --version Prints version information

OPTIONS:

-d, --database <FILE> Specify the path to the database.

-l, --download <URL> Download a remote database.

Running tupm with no arguments will load the database present in

$HOME/.tupm/primary or create a new database if one does not already

exist. A different database path may be specified with the --database

option.

Alternately, a database can be imported from an existing UPM sync

repository with the --download option. (Only HTTP/HTTPS based

repositories are supported. The option to use Dropbox is not

supported.) The repository URL (without the database name appended)

should be provided. By default, a database named "primary" is

downloaded and installed into $HOME/.tupm/primary, unless an alternate

database path was specified with --database. You will be prompted for

the HTTP username and password credentials:

$ tupm --download https://example.edu/repo/

Downloading remote database "primary" from repository "https://example.edu/repo/".

Repository username: username

Repository password:

23708 bytes downloaded from repository.

Database written to: /home/username/.tupm/primary.

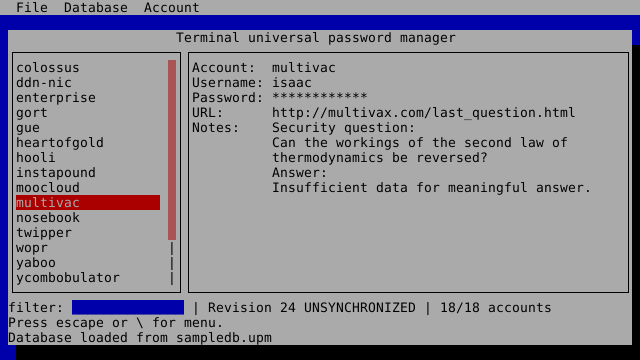

After a database is loaded, you are presented with a user interface

showing a navigable list of accounts, detailed information about the

selected account, a filter box (quickly accessible by pressing /), and

a menu of options accessible by pressing escape or \. Most menu

options have keyboard shortcuts for direct invocation.

For the exceptionally brave among you, the --export command-line

argument will write a full plaintext report of the contents of the

database to standard output. (It goes without saying that such exported

data is not at all protected by encryption and thus highly vulnerable.)

I wrote Tupm as a Rust learning exercise. I'm making it available on the off chance that other developers might find its code useful when interoperating with UPM databases. However, for several reasons, I'd like to discourage anyone from using it directly to manage passwords.

Work on UPM goes back to 2005, and its usage of cryptography would probably be considered less than ideal by 2017 standards. I'm not a cryptographer, but I do have several concerns about the cryptography used in the UPM format.

- Usage of PKCS#12 key derivation. UPM derives a key from the master password using the PKCS#12 v1.0 key derivation function (KDF). The latest PKCS#12 standard declares that this KDF "is not recommended and is deprecated for new usage" and recommends using PBKDF2 instead. (See: [RFC 7292 Appendix B] (https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc7292#appendix-B).) The PKCS#12 KDF does not seem to be commonly used outside of protecting actual PKCS#12 data structures. I'm not aware of any specific weaknesses that have been found, but its deprecation status doesn't inspire much confidence.

- Insufficient KDF iterations. The effectiveness provided by a KDF such as the one specified by PKCS#12 is related to the number of iterations performed. The original PKCS#12 v1.0 document from 1996 used 1024 as an example iteration count, but this was later considered to be insufficient. The count should be as high as possible to increase the cost of brute-force attacks without causing a noticeable delay for the user. My underpowered Asus C201P ARM-based Chromebook can perform 1.5 million iterations/sec of PKCS#12 KDF, so iterations can be quite high. The UPM format uses an iteration count of 20.

- Unauthenticated storage. The UPM cryptosystem does not provide any authenticity of the ciphertext, so an attacker could theoretically modify bits of the ciphertext to cause corruption, solicit unintended behavior from the parsing program, or possibly even yield different but seemingly valid decrypted plaintext. Any future revision of the format should calculate a MAC after encryption and include it in the database format, or ideally simply use an authenticated encryption mode such as GCM.

While Tupm is running, sensitive materials such as the master password, derived keys, and the stored account passwords are stored in memory in the clear, with little or no provision for erasing them when they are no longer needed. This is okay for a proof-of-concept demonstration, but would definitely be not good for a production password manager.

Developing a set of best practices for handling such material in a cross-platform application would be a great research project in and of itself, and probably consider steps such as:

- Zero-on-drop data structures that avoid the possibility of the compiler optimizing away the erasing. Rust's lack of immovable types may also be an issue.

- OS-specific features for each platform, such as

mlock()/munlock()to prevent sensitive data from being swapped to disk, andmprotect()to prevent such data from being saved with core dumps. - Perhaps it will eventually be practical to make use of certain hardware-specific protection features where available, such as Intel Software Guard Extensions (SGX).

In addition to the memory of the Tupm program itself, sensitive information could leak through adjacent programs. For example, passwords shown in the terminal may remain in the scrollback buffer, and passwords copied to the system clipboard remain there until overwritten.

Thanks to Adrian Smith for developing the original UPM programs, Alexandre Bury for the Cursive library used to provide the terminal-based user interface, and the greater Rust community.